This column is a lead commentary in the VoxEU Debate on "Populism"

The distinctive trait of populism is that it claims to represent and speak for ‘the people’, which is assumed to be unified by a common interest. This common interest, the ‘popular will’, is in turn set against the ‘enemies of the people’ – minorities and foreigners (in the case of right-wing populists) or financial elites (in the case of left-wing populists).

Since they claim to represent ‘the people’ at large, populists abhor restraints on the political executive. They see limits on their exercise of power as necessarily undermining the popular will.

What drives populism?

There are essentially two schools of thought on the drivers of populism, one that focuses on culture and another that focuses on economics. The cultural perspective sees Trump, Brexit, and the rise of right-wing nativist political parties in continental Europe as the consequence of a deepening rift in values between social conservatives and social liberals, with the former having thrown their support behind xenophobic, ethno-nationalist, authoritarian politicians. The economic perspective sees populism as the result of economic anxieties and insecurities, themselves due in turn to financial crises, austerity, and globalisation.

Some versions of the cultural argument are problematic. For example, many commentators in the US have focused on the racist appeal of Donald Trump. But racism in some form or another has been an enduring feature of US society and cannot tell us, on its own, why Trump as proved so popular. A constant cannot explain a change.

Other accounts are more sophisticated. The most thorough and ambitious version of the cultural backlash argument has been put forth by Pippa Norris and Ronald Inglehart (2019). They argue that authoritarian populism is the consequence of a long-term generational shift in values. As younger generations have become richer, more educated, and more secure, they have adopted ‘post-materialist’ values that emphasise secularism, personal freedoms and autonomy, and diversity at the expense of religiosity, traditional family structures, and conformity. Older generations have become alienated – effectively becoming ‘strangers in their own land’. While the traditionalists are now numerically the smaller group, they vote in greater numbers and are more active in politics.

A similar argument has been made recently by Will Wilkinson (2019), focusing on the role of urbanisation in particular. He argues that urbanisation serves as a process of spatial sorting that divides society in terms of not just economic fortunes but also cultural values. It creates thriving, multicultural, high-density areas where socially liberal values predominate. And it leaves behind rural areas and smaller urban centres that are increasingly uniform in terms of social conservatism and aversion to diversity.

On the other side of the argument, economists have produced a number of studies that link political support for populists to economic shocks. In what is perhaps the most famous among these, Autor et al. (2017) have shown that votes for Trump in the 2016 presidential election across US communities were strongly correlated with the magnitude of adverse China trade shocks. The greater the loss of jobs due to the rise in imports from China, the higher the support for Trump, everything else being constant. In fact, the China trade shock may have been directly responsible for Donald Trump’s electoral victory in 2016. Their estimates imply that had import penetration been 50% lower than the actual rate over the 2002-2014 period, a Democrat instead of a Republican presidential candidate would have been elected in the critical states of Michigan, Wisconsin, and Pennsylvania, making Hilary Clinton the winner of the election.

Other empirical studies have produced similar results for Western Europe. Higher penetration of Chinese imports have been found to be implicated in the support for Brexit in Britain (Colantone and Stanig 2017a) and the rise of radical right and nationalist parties in continental Europe (Colantone and Stanig 2017a). Austerity (Becker et al. 2017) and broader measures of economic insecurity (Guiso et al. 2017) have been shown to have played a statistically significant role as well. And in Sweden, increased labour market insecurity has been linked empirically to the rise of the far-right Sweden Democrats (Dal Bó et al. 2018).

The cultural and economic argument may seem in tension, if not downright inconsistent, with each other. But reading somewhat behind the lines, one can discern an emerging convergence of some kind. Since the cultural trends – such as post-materialism and urbanisation-promoted values – are of a long-term nature, they do not fully account for the timing of the populist backlash. (Norris and Inglehart posit a tipping point where socially conservative groups have become a minority but still have disproportionate political power.) Indeed, those who advocate for the primacy of cultural explanations do not in fact dismiss the role of economic shocks. They allow that these shocks aggravated and exacerbated cultural divisions, giving authoritarian populists the added push they needed. For example, economic shocks have greatly intensified urbanisation-led cultural sorting. For their part, economic determinists do recognise that economic shocks act not on a blank slate, but on pre-existing societal divisions along sociocultural lines.

What are the implications of the rise of populism?

I pointed out above that populists abhor restraints on the executive. In politics, this is a dangerous approach that allows a majority to ride roughshod over the rights of minorities. Without separation of powers, an independent judiciary, or free media – institutions which all populist autocrats detest – democracy degenerates into the tyranny of those who happen to be currently in power. Elections become a sham: in the absence of the rule of law and basic civil liberties, populist regimes can prolong their rule by manipulating the media and the judiciary at will. Hence the damage that ‘political populism’ can do is limitless.

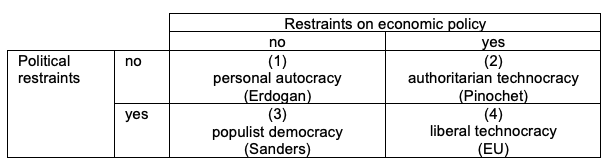

But there is another kind of populism, ‘economic populism’, which we have to keep distinct, and the effects of which can be sometimes positive. Economic populists too reject restraints on the conduct of policy – but now in the economic domain. Autonomous regulatory agencies, independent central banks, and external constraints (such as global trade rules) narrow their policy options and hence need to be overcome. Whether this is a good or bad thing depends on context, and in particular on whose interests those restraints serve. One can imagine regimes that are populist in economic terms but not politically, and vice versa (see Table 1).

Table 1 A taxonomy of regimes

Source: Rodrik (2018a)

Economists dislike populism because the term evokes irresponsible, unsustainable policies that often end in disaster and hurt the most the ordinary people they purportedly aim to help. Macroeconomic populism in Latin America is the chief example of this. They tend to prefer rules, or delegation to autonomous technocratic agencies, because of the tendency of short-term interests to dominate when economic policy is in the hands of politicians. The time-inconsistency of some policies (such as monetary policy) provides the intellectual justification for this stance.

But such restraints on economic policy need not always be desirable. Often commitment to rules or delegation serves to advance the interests of narrower groups, and to cement their temporary advantage for the longer run. Imagine, for example, that a democratic malfunction or random shock enables a minority to grab hold of power. This allows them to pursue their favoured policies, until they are replaced. In addition, they might be able to bind future majorities by undertaking commitments that restrain what subsequent governments can do. In such cases, the results are primarily redistributive rather than efficiency-enhancing. Were a future government to find a way of relaxing restraints of this second kind, society would benefit.

Part of today’s populist backlash is rooted in the belief, perhaps not entirely unjustified, that restraints imposed on economic policy in recent decades have been precisely of the second kind.

Take monetary policy, for example. Independent central banks have played a useful role in bringing inflation down in the 1980s and 1990s. But in a low inflation environment, their exclusive focus on price stability tends to impart a deflationary bias to economic policy. Or consider global trade rules. One can make the argument that the agenda of international trade agreements has increasingly been shaped by special interests – multinational corporations, financial institutions, pharmaceutical and high-tech companies (Rodrik 2018b). The result has been global disciplines that disproportionately benefit capital at the expense of labour. Similarly, while international investor tribunals (as part of investor-state dispute settlement, or ISDS) can be in principle beneficial to both foreign firms and host governments, in practice they have increasingly turned into a redistributive vehicle. They allow foreign investors to effectively pressure governments not to adopt policies that affect their profits adversely, regardless of the public interest.

In Europe, the emphasis on economic integration – removing transaction costs of cross-border transactions – has encouraged rule-making that takes place at considerable distance from democratic deliberation at the national level. EU-wide regulations, fiscal rules, and a common monetary policy imply policy is increasingly made in Brussels and Frankfurt while politics remains in the national capitals (to use political scientist Vivien Schmidt’s evocative distinction). The system serves skilled professionals and internationally oriented companies well, but many others feel excluded. Complaints about the region’s democratic deficit, and the recent populist backlash, are rooted in this style of technocratic policymaking, insulated from politics.

In many of these instances, relaxing the constraints on economic policy and returning policy autonomy to elected governments may well be desirable. This is especially true in times such as these, when much conventional wisdom has been upended by political development and political populism is on the rise. Exceptional times require the freedom to experiment in economic policy.

Franklin D. Roosevelt and his New Deal provide an apt historical example. FDR famously called for “bold, persistent experimentation” in 1932, arguing that correcting the faults of the prevailing economic system required enthusiasm, imagination, and courage to tamper with established arrangements. But to experiment he needed to do away with many of the shackles on economic policy. In 1933, he took the US off the Gold Standard, which had been a major (external) constraint on monetary policy. This allowed the dollar to depreciate and US interest rates to come down. Output received an immediate boost. Many of FDR’s signal economic initiatives were dressed in explicitly populist garb. The 1935 Revenue Act, which introduced a tax on wealth, was known as the ‘soak the rich’ tax. The Social Security Act, providing for financial support to the elderly and the unemployed, was in part a response to the popularity of a plan advanced by a physician named Francis Townsend to provide all elderly Americans with a stipend. In a 1936 address to the Democratic convention, FDR riled against what he called the “economic royalists” – the corporations, financiers, and industrialists who he said had monopolised the economy at the expense of ordinary people.

FDR’s challenge was to both tame and redirect the populist passions the Great Depression had inflamed. Huey Long, a demagogue and the authoritarian governor of Louisiana, was one vocal nemesis, calling for a radical redistribution of wealth in the country. Another was the fascistic Father Charles Coughlin, with tens of millions of followers on the radio. His economic reforms, FDR explained, were needed not only to serve people better, but also for the “survival of democracy”.

We now know that FDR was right. It was impossible to save either the economy or democracy without significantly relaxing the prevailing harnesses on economic policy. There are times when economic populism may be the only way to forestall its much more dangerous cousin, political populism.

Author’s note: This column based on a Project Syndicate article (Rodrik 2019) and a paper in AEA Papers & Proceedings (Rodrik 2018a).

References

Autor, D, D Dorn, G Hanson and K Majlesi (2017), “Importing Political Polarization? The Electoral Consequences of Rising Trade Exposure”.

Becker, S O, T Fetzer and D Novy (2017), “Who voted for Brexit? A comprehensive district-level analysis”, Economic Policy 32(92): 601–650.

Colantone, I and P Stanig (2017a), “Global Competition and Brexit”.

Colantone, I and P Stanig (2017b), “The Trade Origins of Economic Nationalism: Import Competition and Voting Behavior in Western Europe”.

Dal Bó, E, F Finan, O Folke, T Persson, and J Rickne (2018), “Economic Losers and Political Winners: Sweden’s Radical Right”.

Guiso, L, H Herrera, M Morelli and T Sonno (2017), “Demand and Supply of Populism”, EIEF Working Paper 17/03.

Norris, P and R Inglehart (2019), Cultural Backlash: Trump, Brexit, and Authoritarian Populism, Cambridge Univeristy Press.

Rodrik, D (2018), “Is Populism Necessarily Bad Economics?” AEA Papers & Proceedings 108.

Rodrik, D (2019), “What’s Driving Populism?” Project Syndicate, 9 July.

Wilkinson, W (2019), “The Density Divide: Urbanization, Polarization, and Populist Backlash”, Niskanen Center Research Paper.