Prices across the OECD area have risen at an exceptionally fast pace over the last couple of years, reaching levels not seen in decades in many OECD countries. Meanwhile, nominal wages, despite picking up in many countries compared to the past decade, have not kept pace. As a result, real wages declined for several quarters in most OECD countries, and at the end of 2022, were below their Q4 2019 level by an average of -2.2% in 24 of the 34 OECD countries with available data (OECD 2023). Even in the remaining ten countries, however, inflation had eroded most of the nominal wage growth.

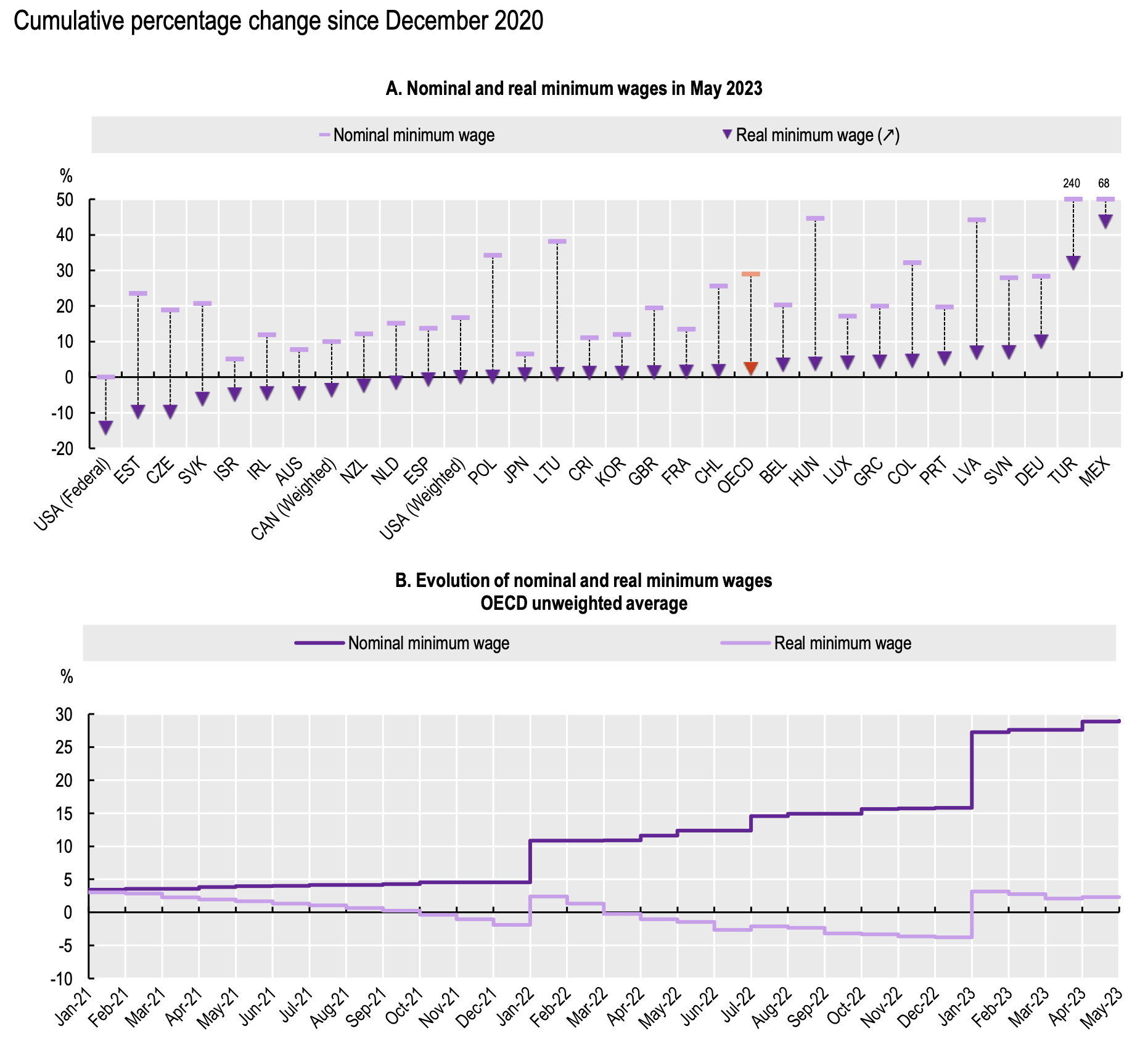

Low-paid workers are particularly at risk since they have less leeway to deal with increases in the cost of living through savings or borrowings and a higher proportion of their spending goes to energy and food. However, between December 2020 and May 2023, almost all OECD countries took measures to increase their minimum wages and this has allowed minimum wages to keep pace with inflation: on average across OECD countries, nominal statutory minimum wages have increased by 29% between December 2020 and May 2023 while prices increased by 24.6% over the same period (Figure 1).

There are, however, major differences across countries that can be explained by differences in the timing, frequency, and size of the nominal increases. In most countries, the minimum wage is adjusted annually with a usually short delay between the decision and the application. In other countries, the minimum wage is adjusted annually or biannually but with a slightly longer delay, which may make a difference in times of high and/or rising inflation. Finally, in some countries, there is no regular adjustment, which may result in long delays and major losses in purchase power. In the US, for instance, the federal minimum wage has not been increased since 2009 (but minimum wages at the state and local level have gained much more prominence in the meantime).

The revision of minimum wages may be subject to government discretion or can take place automatically in case of indexation. In some OECD countries – notably, Belgium, Canada (since April 2022), France, Israel, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and Poland – there is a form of automatic indexation for the minimum wage at the national level. But automatic indexation may also exist for subnational minimum wages, as is the case in Canada, Switzerland, and the US. Furthermore, indexation may be anchored to wages or prices. Finally, multiple increases can also take place in years of high inflation, as in Belgium, France, and Luxembourg (however, in Luxembourg, the second increase in 2022 was postponed on the basis of a tripartite agreement.). A few countries have an automatic indexation that kicks in only if social partners fail to find an agreement (Colombia and the Slovak Republic).

Figure 1 Minimum wages have managed to keep pace with inflation

Note: Statistics refer to the cumulative percentage change in March 2023 relative to December 2020 for New Zealand. To date, statistics in Panel A, do not include planned increases in the minimum wage for Australia, the Netherlands, Poland, and Türkiye in July 2023 (+8.7%, +3.1%, +3.2% and +34%, respectively). OECD is the unweighted average of all countries shown except the US (weighted). Canada (weighted) is a Laspeyres index based on the minimum wage of provinces and territories (excluding the Federal Jurisdiction) weighted by the share of employees of provinces and territories in 2019. US (weighted) is a Laspeyres index based on the minimum wage of states (not including territories like Puerto Rico or Guam) weighted by the share of nonfarm private employees by state in 2019. For further details on the minimum wage series used in this Chart and its evolution by country, see Annex Table 1.C.2 and Annex Figure 1.C.1.

Source: OECD Employment database, OECD (2023), “Prices: Consumer prices”, Main Economic Indicators database (accessed on 4 July 2023), and Monthly CPI Indicator (Australian Bureau of Statistics).

These minimum wage increases, especially when linked to a formula that automatically indexes them to past inflation, are raising two main concerns: (1) a squeezing of the wage distribution; and (2) the risk of a price wage spiral, especially in case of high inflation and uncertainty. In fact, increases in minimum wages often have spillover effects higher in the wage distribution and can therefore have an aggregate effect on wage growth that goes well beyond the direct beneficiaries. This happens because minimum wages are used, formally or informally, as a benchmark in the negotiation of collective and individual wages as well as a reference for certain social minima.

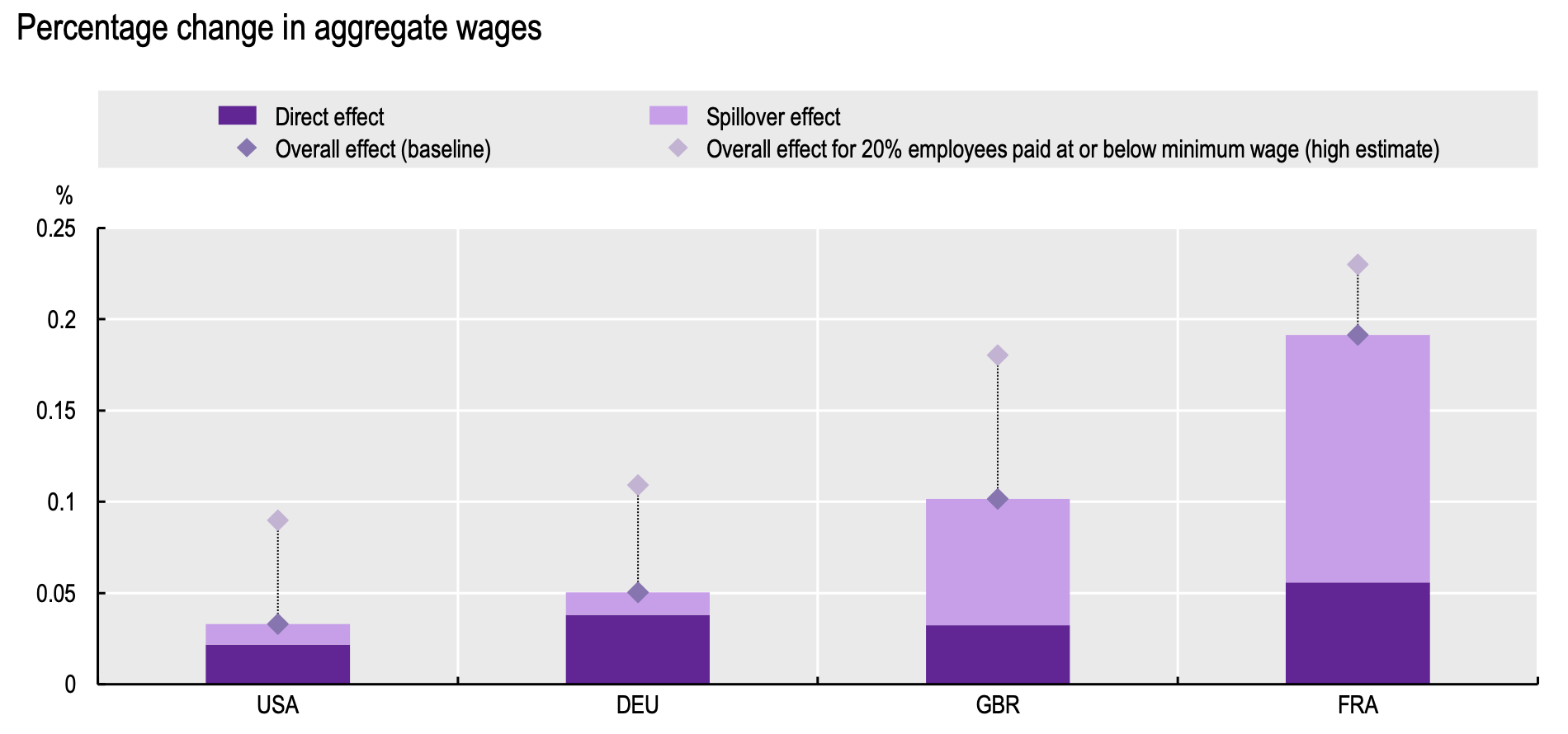

Figure 2 simulates the impact of the minimum wage increase on the growth in aggregate wages, accounting for both its direct effect (on those workers paid at or below the minimum wage) and its spillover effect (on those workers paid above the minimum wage). The impact of a 1% increase in the minimum wage is simulated using estimates of spillover effects from the literature (Aeberhardt et al. 2012, Biewen et al. 2012, Gautier et al. 2022, Giupponi et al. 2022, Gopalan et al. 2021) and taking the share of the minimum wage earners in a baseline year (see OECD 2023 for more details). This exercise suggests that a minimum wage increase of 1% can be expected to influence aggregate wage growth between 0.03% (in the US, using the share of minimum wage earners of state level minimum wages) and 0.2% (in France). The magnitude of these estimates is in line with that found by Koester and Wittekopf (2022) who conducted a similar analysis with another data source and only included the direct effects.

These effects could be, nonetheless, somewhat underestimated. First, spillover effects could be stronger in a high inflation environment when minimum wage increases are larger and more frequent. Second, these estimates do not account for possible feedback loop on the minimum wage, notably in a country like France where the minimum wage is also indexed to half of the past increase of the real wage of blue collar workers (but even in a country like France, the increases have not led to a price wage spiral and are considered by the French central bank as compatible with a gradual decline in inflation in 2023 and a return towards the 2% target by end 2024 to end 2025, see Baudry et al. 2023). However, the overall impact is likely to remain relatively limited in magnitude: even assuming a higher share of minimum wage earners (20%), Figure 2 shows that the aggregate wage effects range between 0.09% (in the US) and 0.23% (in France) suggesting a rather limited risk of major impact on wage inflation of minimum wage increases.

Figure 2 Impact of a 1% increase in the minimum wage on aggregate wages

Note: The estimated impact of a minimum wage increase on aggregate wages is based on the share of employees paid at or below the minimum wage in 2018 for France and Germany (11% and 8.4% of employees, respectively), in 2019 and 2021 22 for the UK (5.9% of employees) and in 2022 for the US (6% of employees). The high estimate corresponds to the estimated impact of raising the proportion of employees paid at or below the minimum wage to 20%. The direct effect refers to the impact of a 1% increase in the minimum wage of employees paid at or below the minimum wage on the aggregate wage growth. The spillover effect estimates the impact of this increase for employees paid above the minimum wage on the total wage bill through the estimated spillover coefficients based on empirical evidence for various academic studies – see Box 1.8. Note that these estimates do not account for possible feedback loops on the minimum wage, notably in a country like France where the minimum wage is also indexed to half of the past increase of the real wage of blue collar workers.

Reading: In France, assuming the share of employees paid at or below the minimum wage at its 2018 level (11%), a 1% increase in the minimum wage would lead to a 0.06% increase in the total wage bill (direct effect). This increase in the minimum wage would also have a spillover effect on all earnings above the minimum wage, but in a lesser proportion (+0.2% for employees paid 1.2 times the minimum wage and +0.1% from 1.5 times the minimum wage onwards) through the adaptation of conventional wage scales, resulting in an increase of 0.14% of the total wage bill (spillover effect). In total, this increase would increase the total wage bill by 0.19%.

Source: Authors’ estimations based on the European Union Structure of Earnings Survey (EU-SES) scientific-use files (SUFs) for France and Germany, the UK Labour Force Survey for the UK, and the Current Population Survey (CPS) for the US.

On top of the effect of a minimum wage increase on aggregate wages, a second issue is how firms which employ minimum wage workers respond to increases in the minimum wage, and, in particular, if and how much these firms are able to pass higher wages onto prices. Most empirical studies agree that part of minimum wage increases is passed on to consumers (e.g. Harasztosi and Lindner 2019). However, Lindner (2022) has calculated that in the UK, an increase in the minimum wage of 20% would still only lead to an increase in inflation of 0.2% − which compared to the inflation rates observed in the last quarters is small.

Beyond the risk of a price wage spiral, which is likely to be limited as just illustrated before, there are other aspects to consider in assessing the merits and pitfalls of regular and sustained minimum wage increases in times of high inflation, especially when linked to an automatic indexation to past price developments. On the one hand, these increases contribute to safeguarding the purchasing power of minimum wage earners and may help to reduce in-work inequality (or at least limit its increase, in cases where high-wage workers are able to negotiate wage increases that keep pace with inflation while low-wage workers are not). Automatic indexation, more specifically, may also increase visibility and transparency for firms, which can more easily anticipate future increases – for example, Clemens and Strain (2022) find lower non-compliance in US states where the minimum wage is indexed – as opposed to discretionary increases. On the other hand, automatic indexation mechanisms may reduce the margins of judgement that governments, social partners or commissions have in deciding future increases (e.g. in a period of stagflation, decision-makers may have to weigh the risk of loss of purchasing power against the risk of job losses), limit the role of social partners in setting wages, and may also lead to excessive compression of the wage distribution if the rest of the wage structure does not move, with consequences on individual careers, as well as on the design of redistribution policies.

While keeping these potential pitfalls in mind, in the context of high inflation, we believe that it remains important to ensure regular adjustments of statutory minimum wages as real gains tend to be eroded as inflation remains high. Results above suggest however that minimum wages proved, on average across OECD countries, to be a useful policy instrument to protect the most vulnerable workers from rising prices. Adjustments in nominal minimum wages have helped contain the impact of inflation on the purchasing power of low-paid workers. Going forward, statutory minimum wages should continue to adjust regularly. Our analysis shows that the risk of further fuelling inflation by increasing minimum wages is limited. However, countries will need to carefully assess the risk that the sole increase of minimum wage – without increases higher up in the wage distribution – may lead to excessive compression of the wage distribution, with a negative impact on individual careers and implications for designing redistribution policies.

References

Aeberhardt, R, P Givord and C Marbot (2012), “Spillover Effect of the Minimum Wage in France : An Unconditional Quantile Regression Approach”, Série des documents de travail de la Direction des Études et Synthèses Économiques, Insee (Institut national de la statistique et des études économiques), Paris.

Baudry, L, E Gautier and S Tarrieu (2023), "Wage negotiations in a context of rising inflation", Banque de France, Paris.

Biewen, M, B Fitzenberger and M Rümmele (2022), “Using Distribution Regression Differencein-Differences to Evaluate the Effects of a Minimum Wage Introduction on the Distribution of Hourly Wages and Hours Worked”, IZA Discussion Papers No. 15534.

Clemens, J and M Strain (2022), “Understanding “Wage Theft”: Evasion and Avoidance Responses to Minimum Wage Increases”, Labour Economics 102285.

Gautier, E, S Roux and M Suarez Castillo (2022), “How do wage setting institutions affect wage rigidity? Evidence from French micro data”, Labour Economics 78: 102232,

Giupponi, G, R Joyce, A Lindner, T Waters, T Wernham and X Xu (2022), “The Employment and Distributional Impacts of Nationwide Minimum Wage Changes”, working paper.

Gopalan, R, B H Hamilton, A Kalda and D Sovich (2021), “State Minimum Wages, Employment, and Wage Spillovers: Evidence from Administrative Payroll Data”, Journal of Labor Economics 39(3): 673-707.

Harasztosi, P and A Lindner (2019), “Who Pays for the Minimum Wage?”, American Economic Review 109(8): 2693-2727.

Koester, G and D Wittekopf (2022), “Minimum wages and their role for euro area wage growth”, ECB Economic Bulletin 3/2022.

Lindner, A (2022), “It’s time to increase the National Living Wage to help with the cost of living”, UCL Policy Lab.

OECD (2023), OECD Employment Outlook 2023, OECD Publishing.