With US inflation reaching 7.9% in February 2022, the Federal Reserve moved to increase the federal funds rate by 0.25 percentage points at its March meeting. The Federal Open Market Committee’s (FOMC) latest Summary of Economic Projections (2022), released at the same meeting, projects interest rates to reach 1.9% by the end of 2022. In response, there has been much discussion over the plausibility that the central bank can achieve a soft landing without pushing the US economy into a recession.

While engineering a soft landing is historically very rare, Fed Chair Jerome Powell told lawmakers in early March that he believes achieving a soft landing is “more likely than not” (Powell 2022). The FOMC’s March forecast (FOMC 2022), as well as the consensus forecast from the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia’s Survey of Professional Forecasters (FRBP 2022), supports this claim: in both forecasts, inflation recedes to below 3% by 2023 and unemployment remains below 4%.

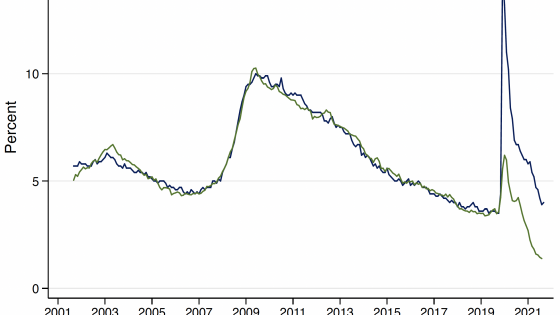

To examine the plausibility of the Fed’s forecasts, we look at quarterly data going back to the 1950s and calculate the probability that the economy goes into a recession within the next 12 and 24 months, conditioning on alternative measures of inflation and unemployment. Our analysis is motivated by the fact that overheating conditions like low unemployment and high inflation are usually followed by recessions in the near-term. For example, Fatas (2021) shows how the US economy has never displayed significant periods of low and stable unemployment, such as those predicted by the FOMC.

Our central finding is that given the current inflation of nearly 8% and unemployment below 4%, historical evidence suggests a very substantial likelihood of recession over the next 12 to 24 months.

Historical evidence suggests high probability of recession

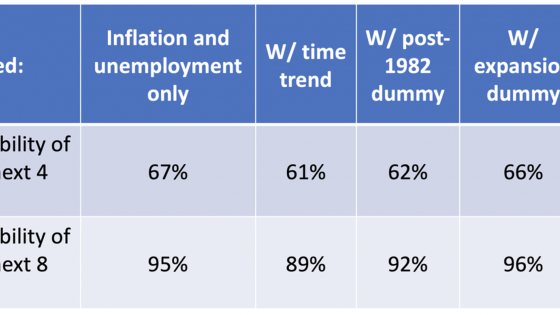

Table 1 shows the historical probability of a recession occurring within the next one and two years, conditional on contemporaneous measures of CPI inflation and the unemployment rate. The results indicate that lower unemployment and higher inflation significantly increase the probability of a subsequent recession. Historically, when average quarterly inflation rises above 5%, the probability of a recession over the next two years is above 60%, and when the unemployment rate drops below 4%, the probability of a recession over the next two years approaches 70%.

Since 1955, there has never been a quarter with average inflation above 4% and unemployment below 5% that was not followed by a recession within the next two years.

Table 1 Historical probability of a recession conditional on different levels of CPI inflation and unemployment, using data from 1955-2019

The above results do not reflect our use of the CPI rather than alternative inflation measures, or the use of the unemployment rate rather than alternative labour market tightness measures. Measuring labour market tightness with the job vacancy rate, which we have advocated for in our prior work (Domash and Summers 2022), suggests an even higher probability of recession over the next 12 and 24 months. Similarly, using Core PCE inflation or wage inflation rather than the CPI also yields the same conclusions.

Some may argue that the historical data presented in these tables overstate the probability of recession, since there has been a trend towards greater business cycle stability in recent decades. Motivated by this concern, and to make maximum use of available information, we use a probit model to predict the probability of a future recession based on current economic conditions and controlling for a time trend.

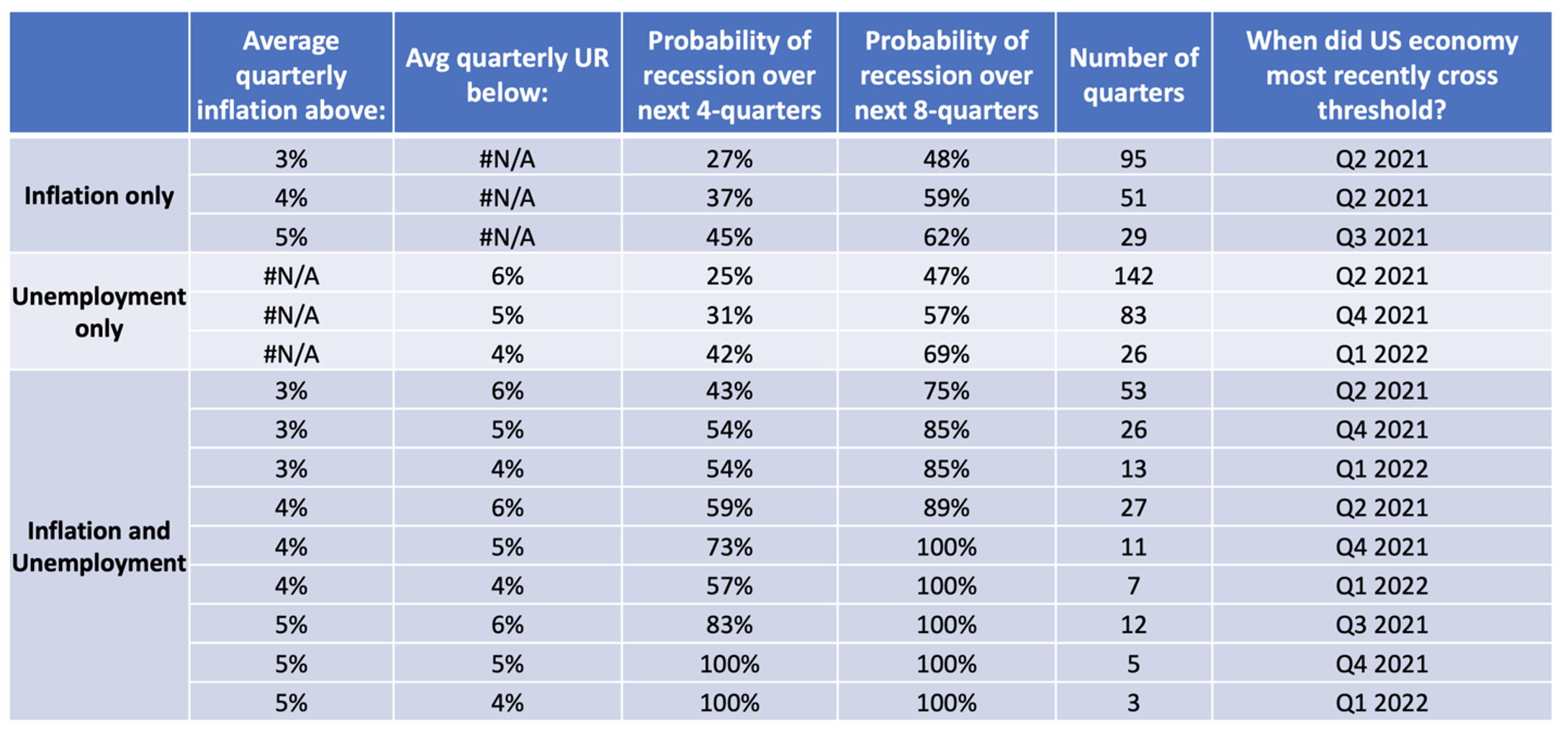

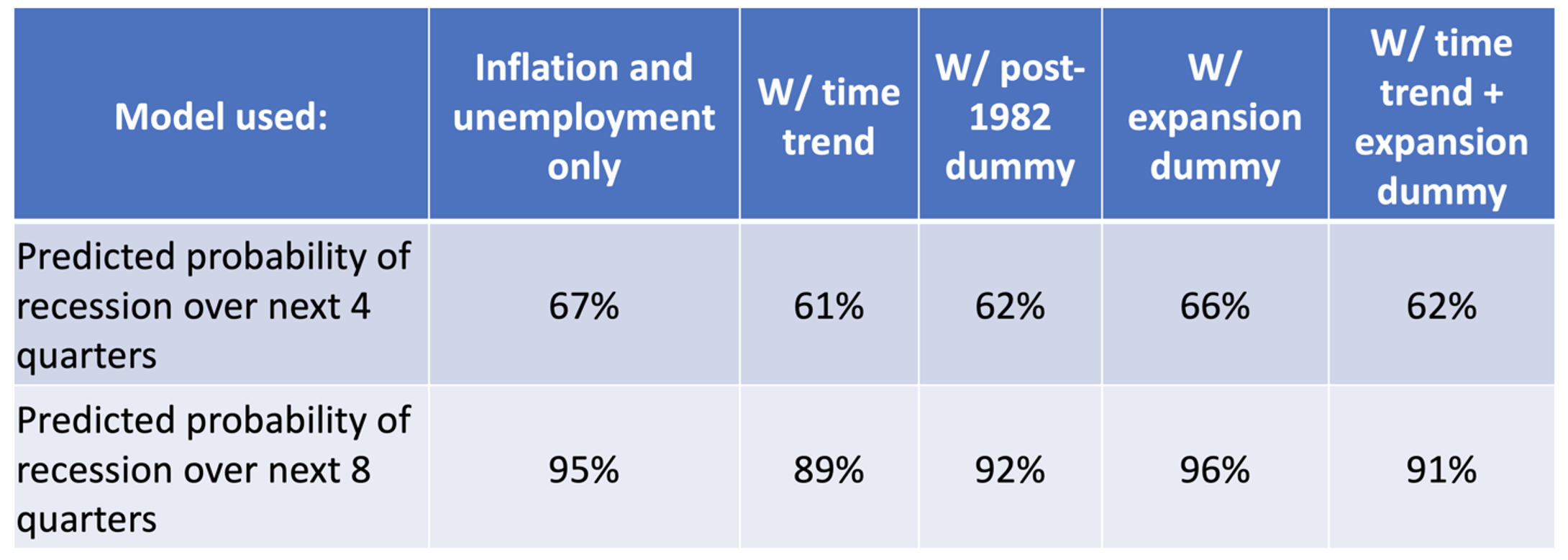

Table 2 presents the results from our probit models, showing the predicted probabilities of a recession occurring over the next 12 and 24 months for five different model specifications. In our baseline model, we use a four-quarter trailing average of inflation and a one-quarter lag of unemployment as our main explanatory variables. To allow for the possibility that recession probabilities have declined over time, we also have specifications that include a time trend (column 2) and a dummy for years after 1982 (column 3). We find in our regressions that a trend towards greater business cycle stability does not appear in any significant way once one controls for economic conditions. Finally, we include a specification with a dummy for whether the economy is more than six-quarters into an economic expansion (column 4), and with the time trend and expansion dummy (column 5).

Table 2 Predicted probabilities of a recession occurring over the next 12 and 24 months

These results suggest a very high likelihood of recession in the coming years and are robust across many model specifications. Moreover, the findings do not reflect our choice to use the CPI as the inflation measure or the unemployment rate as the slack measure. Using wage inflation, rather than the CPI, results in higher predictions of the probability of recession, and using Core PCE inflation results in similar predictions. Replacing the unemployment rate with the vacancy rate (which we believe to be a better tightness indicator) also yields higher predicted probabilities of a recession over the next years.

Overall, the evidence we present suggests that engineering a soft landing is a very difficult thing to do in a rapidly growing, inflation economy.

Soft landings are historically unprecedented in the US

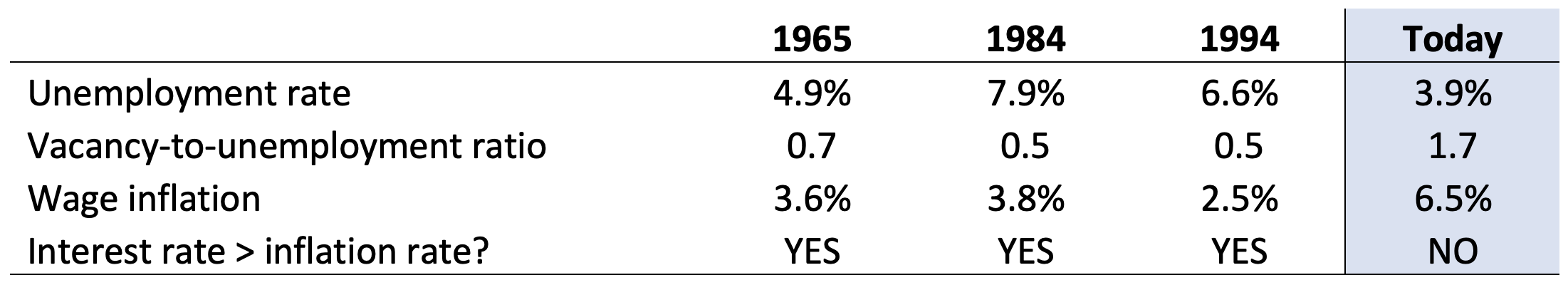

Some have argued that there are grounds for optimism on the basis that soft-ish landings have occurred several times in the post-war period – including in 1965, 1984, and 1994. We show, however, that inflation and labour market tightness in each of these periods had little resemblance to the current moment. Table 3 summarises the labour market conditions during these alleged soft landings.

Table 3 Labour market conditions today compared to past periods

Note: This table uses quarterly averages from the first quarter of the tightening cycle

In all three episodes, the Federal Reserve was operating in an economy with an unemployment rate significantly higher than today, a vacancy-to-unemployment ratio significantly lower than today, and wage inflation still below 4%. In these historical examples, the Federal Reserve also raised interest rates well above the inflation rate – unlike today – and explicitly acted early to pre-empt inflation from spiralling, rather than waiting for inflation to already be excessive. These periods also did not involve major supply shocks such as those currently experienced in the US.

With inflation nearing 8% and unemployment below 4%, the Fed today is way behind the curve, and now has to play catch-up to try to tame price increases. Rather than grounds for optimism, the historical experience in the US is that slowing rapidly accelerating inflation always leads to substantial increases in economic slack. Our conclusion echoes Ha et al. (2022), who argue that bringing inflation back to target likely requires a much more forceful policy response than currently anticipated. Moreover, none of the calculations in this column accounts for the recent supply shocks associated with the war in Ukraine, which will only increase the probability of recession even further. We therefore believe that the likelihood that the Fed achieves a soft landing in the economy is low.

References

Domash, A and L Summers (2022), “How tight are US Labour Markets?”, VoxEU.org, 17 March.

Fatas, A (2021), “The short-lived high-pressure economy”, VoxEU.org, 27 Oct.

Federal Open Market Committee (2022), “FOMC summary of economic projections”, 16 March.

Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia (2022), “First quarter 2022 survey of professional forecasters”, Research Department, Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia. 11 February.

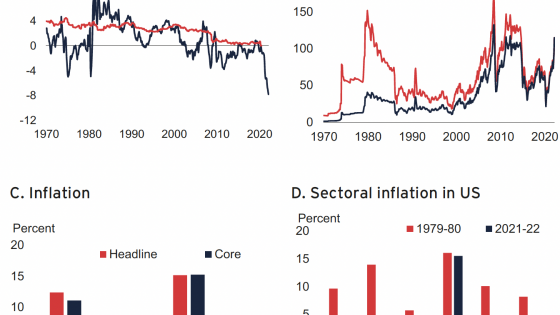

Ha, J, M A Kose, and F Ohnsorge (2022), “Today’s inflation and the Great Inflation of the 1970s: Similarities and differences”, VoxEU.org, 30 March.

Powell, J H (2022), “House hearing on monetary policy and the state of the economy”, National Cable Satellite Corporation, 2 March.