At the turn of the century, the size of China’s economy (measured in US dollars) was close to that of Italy and only 12% of US GDP. Meanwhile, India’s economy was roughly the size of the Netherlands and well outside the world’s ten largest economies. Economic convergence between emerging markets (EMs) and developed economies was notable mostly for its absence (Barro and Sala-i-Martin 1992), and the idea that China, India and other large EMs would become dominant forces in the global economy appeared fanciful. Yet, by 2022, China had become the world’s second-largest economy, with its GDP close to 80% of the US, while India is now the world’s fifth-largest economy.

Twenty years since Goldman Sachs first set out long-term growth projections for the BRICs economies (O’Neill 2001, Wilson and Purushothaman 2003), we have updated, expanded, and extended our long-term projections, incorporating new data and new methods (Daly and Gedminas 2022).

Our revised projections now cover 104 countries, and we have extended our projection horizon from 2050 to 2075.

The risks involved in projecting far into the future remain substantial, and we view the results of this process less as a forecast and more as a method of uncovering broad global dynamics and their long-term implications. One advantage of making long-term projections of this type is that cyclical volatility tends to smooth out over time, leaving output to be determined by more structural factors – labour force growth, trends in capital accumulation and technology convergence. We think there is significant value in gathering all the information we have on these factors and incorporating that information into a coherent model for a broad range of economies.

The forecast model that we use, together with the changes we have made relative to our previous projections, are discussed in detail in Daly and Gedminas (2022).

Four major themes for the global economy

In our updated projections, we identify four major themes for the global economy:

Theme #1: Slower global potential growth, led by weaker population growth

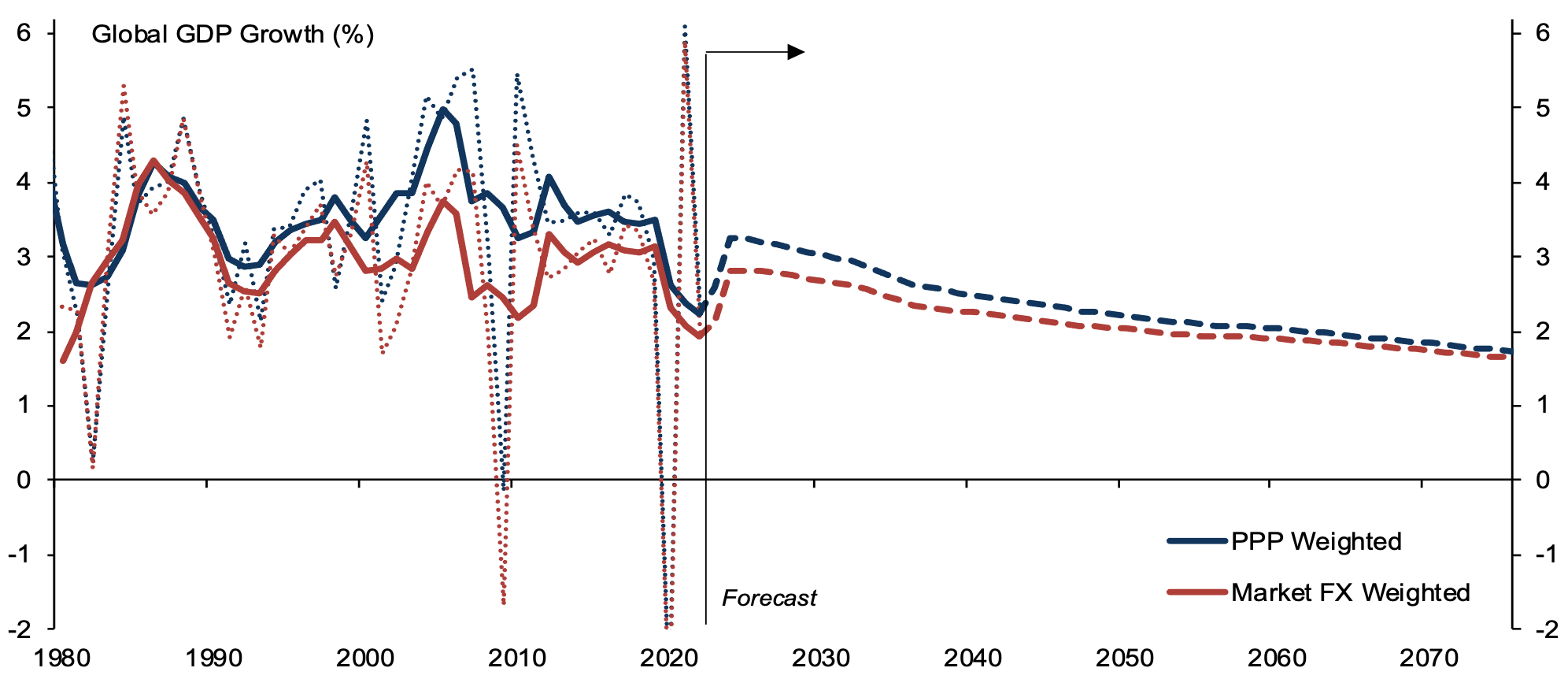

Global growth has slowed from an average of 3.6% per year in the ten years to the Global Crisis, to 3.2% per year in the decade prior to the Covid pandemic (measured on a market-weighted basis). The slowdown has been relatively broad-based, affecting both developed and emerging economies. It has reflected a combination of both slower global population growth and weaker productivity growth, with the latter appearing to be linked to a slowdown in the pace of globalisation. Our projections imply that we have passed the high-water mark of potential global growth, with growth averaging 2.8% between 2024 and 2029 and on a gradually declining path thereafter (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Global potential growth on a gradually declining path

Note: Global GDP growth; solid line - 5Y centred average; dotted line - annual growth.

Source: GS (2022); IMF

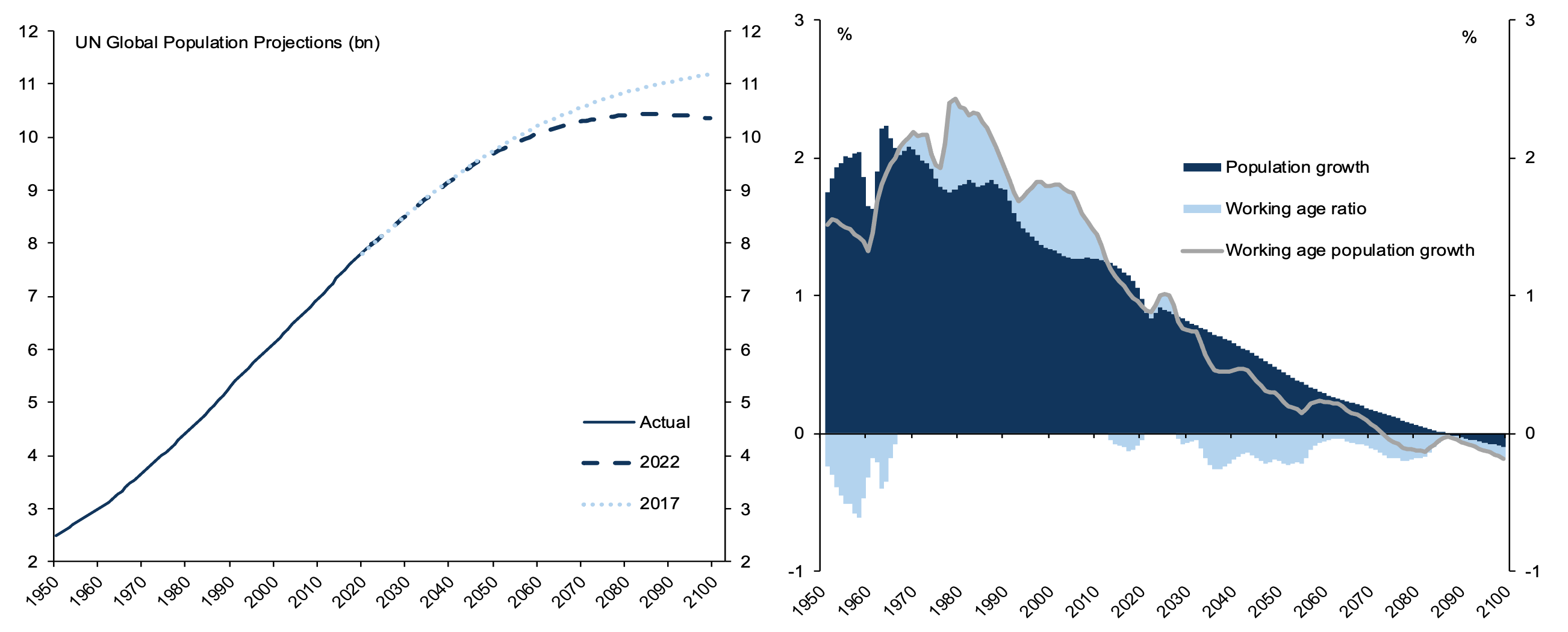

Most of this projected slowdown is due to demographics. Global population growth has halved over the past 50 years, from around 2% per year to less than 1% currently, and UN population projections imply that it will fall close to zero by 2075 (Figure 2). While some of this slowdown had previously been anticipated, population projections are also being revised lower (the global population is now expected to peak at around 10 billion people, having previously been expected to rise to more than 11bn). This is a ‘good problem’ to have, in that reducing global population growth is a necessary condition for long-term environmental sustainability. Nevertheless, this adjustment to weaker population growth and ageing populations presents several economic challenges (most notably, from rising healthcare and retirement costs). The number of developed and EM economies for which population ageing represents a serious economic challenge is likely to rise steadily over the coming decades.

Figure 2 Global population growth has halved since the 1960s/70s and the projected peak population is now falling

Note: UN global overall population workin-age population projections.

Source: United Nations

Theme #2: EM convergence remains intact, led by Asia’s powerhouses

While real GDP growth has slowed in both developed and emerging economies, in relative terms, EM growth continues to outstrip developed economy growth. The pace of this convergence had slowed slightly relative to the 2000s but is significantly faster than in the decades prior to this (when cross-country income convergence was the exception rather than the norm). Maintaining income convergence implies that the share of global GDP accounted for by EMs will continue to rise over time; their incomes will converge slowly towards developed economy levels, and the distribution of global income will shift towards this growing group of ‘middle-income’ economies.

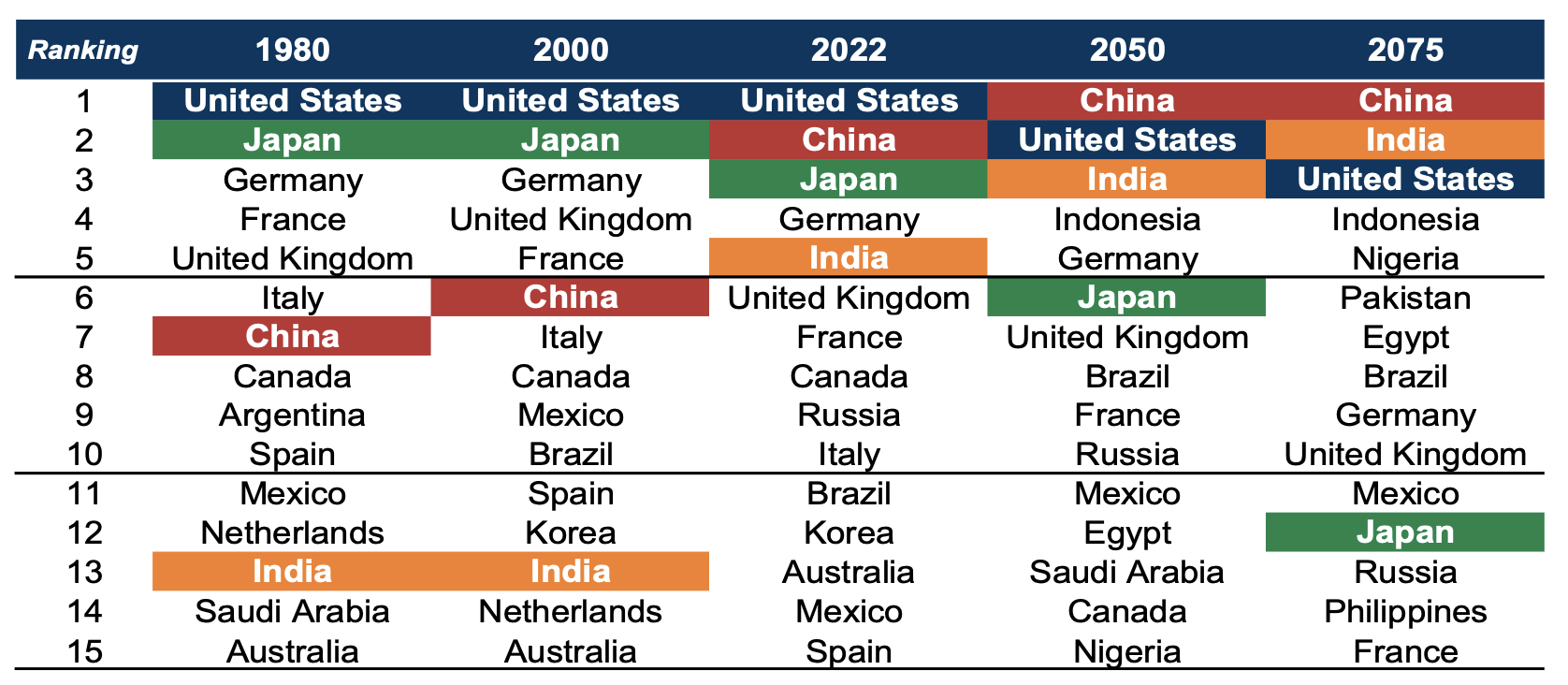

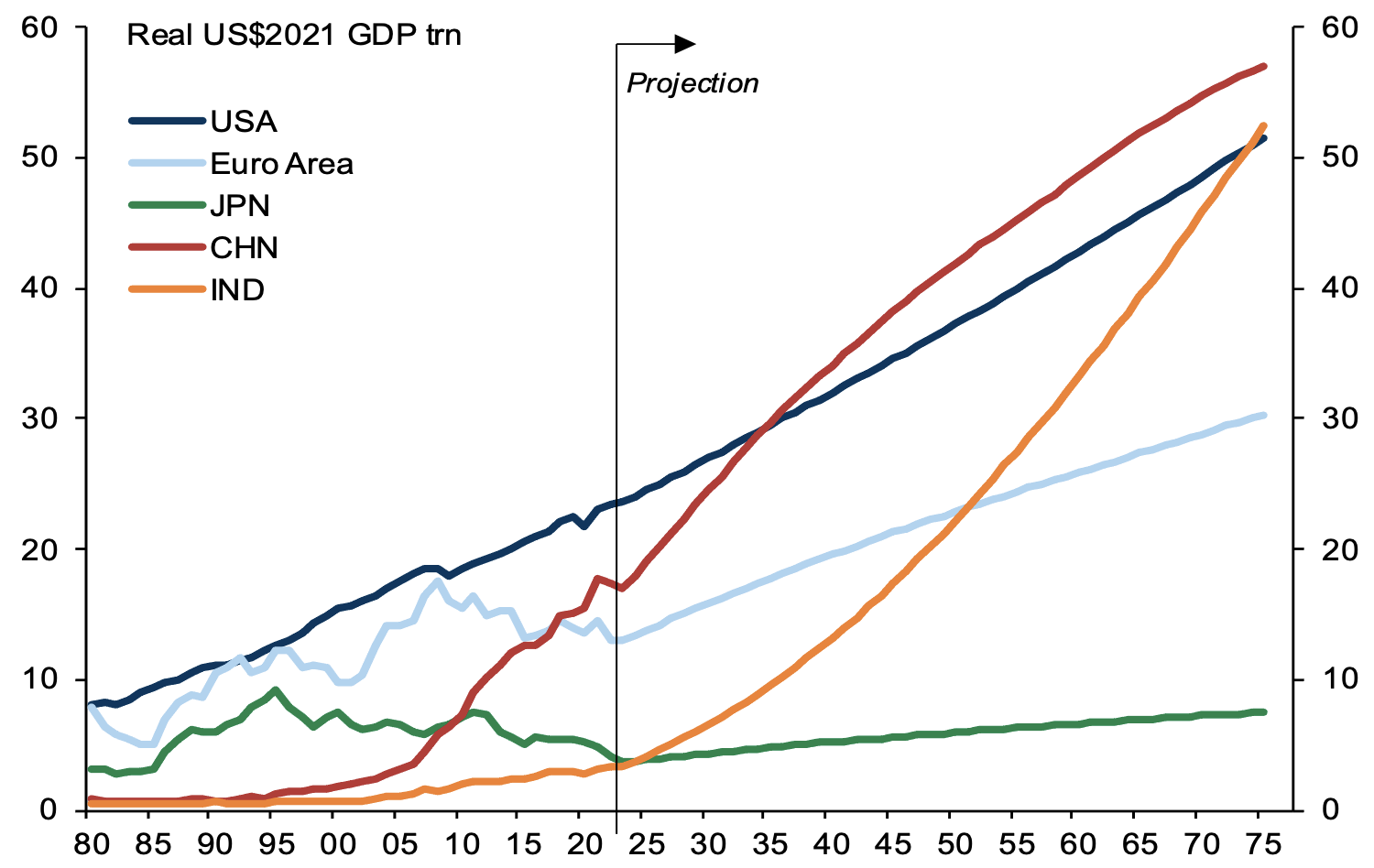

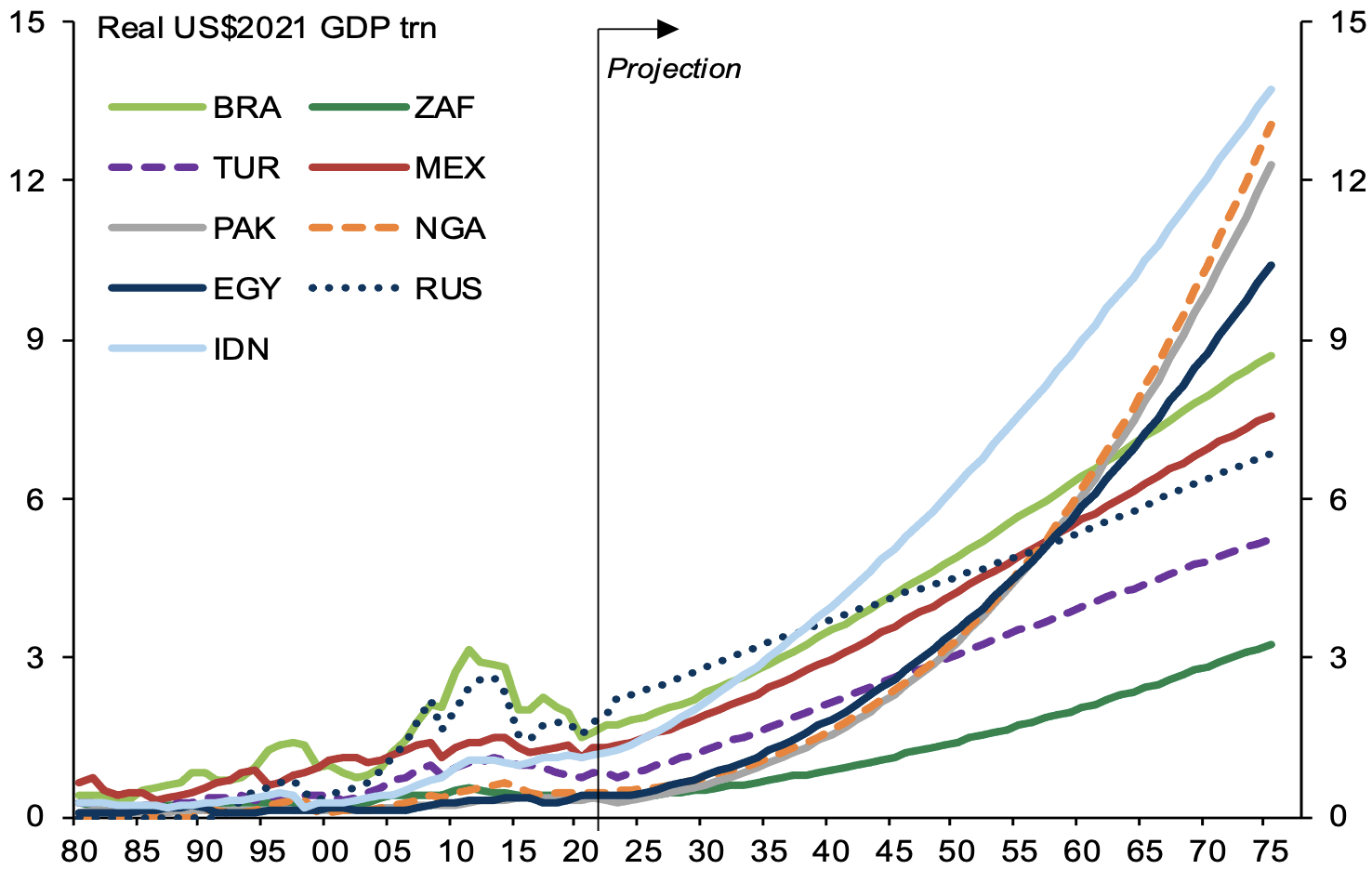

Although GDP growth disappointed our 2011 projections in the majority of economies, the pattern was far from uniform. China, India, and Indonesia all slightly outperformed our forecasts, while Russia, Brazil, and Latin America more generally significantly underperformed our projections. As a consequence, we expect that the weight of global GDP will shift (even) more towards Asia over the next 30 years. In 2050, our projections imply that the world’s five largest economies (measured in US dollars) will be China, the US, India, Indonesia, and Germany (with Indonesia displacing Brazil and Russia among the list of largest EMs over this horizon; Figure 3). If we extend the projection horizon to 2075, the prospect of rapid population growth in countries such as Nigeria, Pakistan and Egypt implies that – with the appropriate policies and institutions – these economies could become some of the largest in the world (Figure 4).

Figure 3 Our projections imply that China, the United States, India, Indonesia, and Germany will be the world's five largest economies in 2050

Note: World's largest economies (measured in USD).

Source: GS (2022)

Figure 4a China to overtake US in around 2035, while India should catch up by 2075

Figure 4b EM leaderboard to change significantly by 2075

Note: GDP level projections in Real (2021) USD trillion.

Source: GS (2022)

Theme #3: A decade of US exceptionalism that is unlikely to be repeated

Uniquely among large, developed economies, the US slightly outperformed our long-term real GDP growth projections over the past decade. Moreover, with the US dollar also appreciating sharply over this period, the relative dollar value of the US economy significantly outstripped our expectations. It is not unusual for individual countries to significantly out or underperform long-term projections of this type over five- to ten-year periods – indeed, other countries outperformed by more than the US. The question is whether this outperformance is likely to be repeated over the next decade. On balance, we think not. US potential growth remains significantly lower than that of large EM economies, including China and (especially) India. Moreover, the dollar’s exceptional strength in recent years has resulted in it rising significantly above its PPP-based fair value, and this deviation implies that it is more likely to depreciate over the coming ten years.

Theme #4: Less global inequality, more local inequality

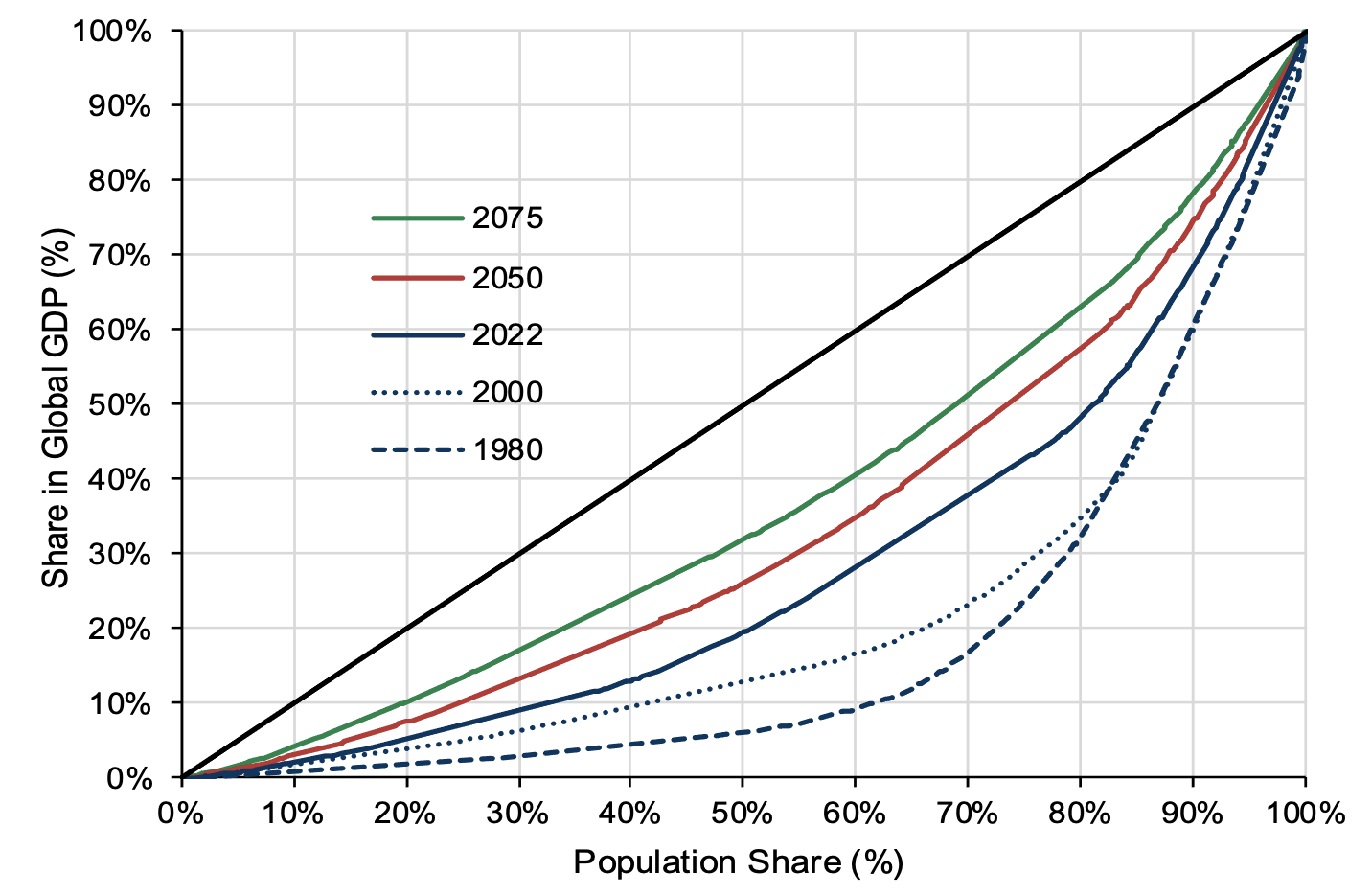

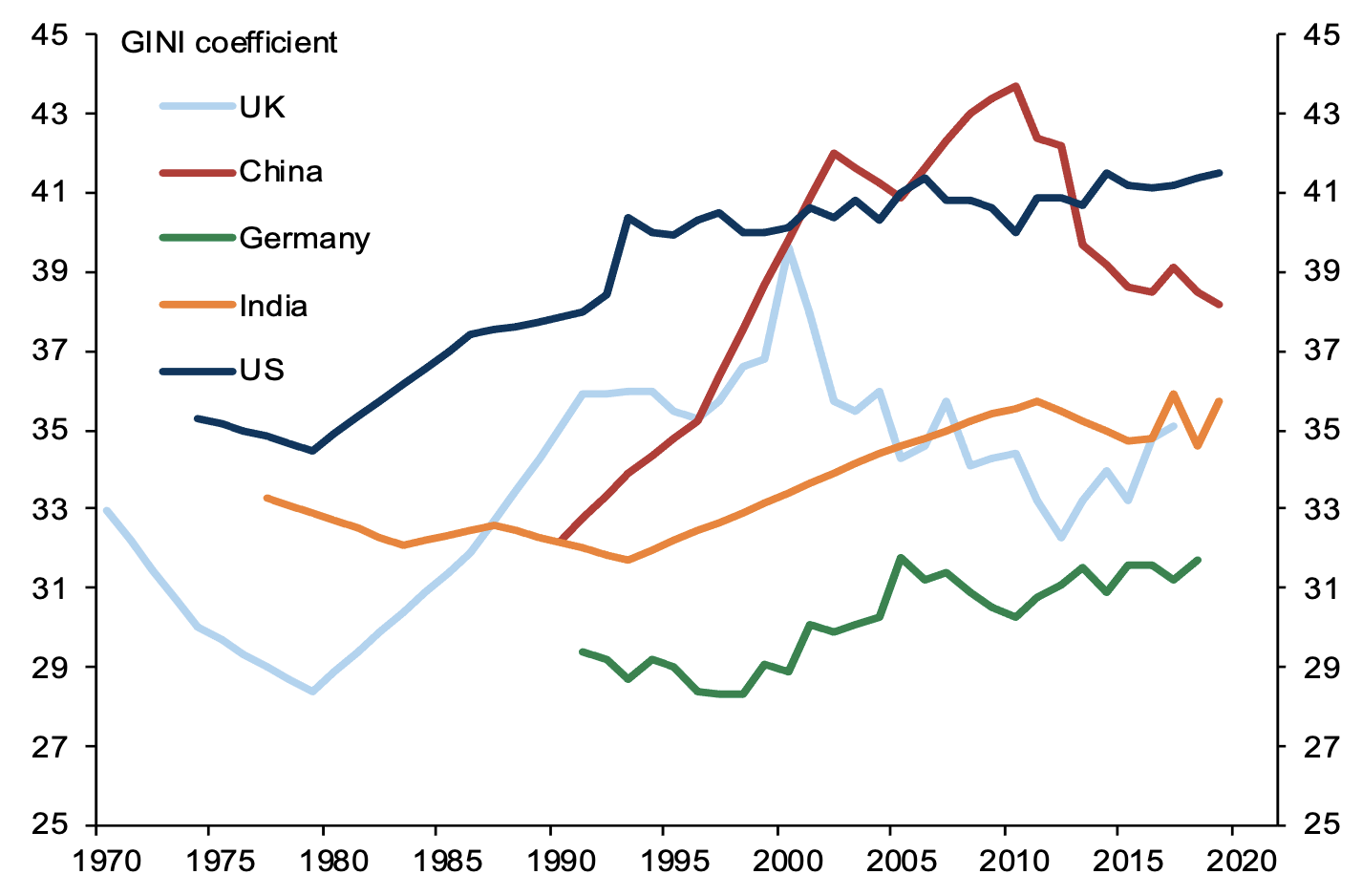

Twenty years of EM convergence has resulted in a more equal distribution of global incomes (Figure 5). This has been an underappreciated benefit of globalisation over the past 20-25 years, and our projections imply that it will continue. However, while income inequality between countries has fallen, income inequality within countries has risen. And, as governments are responsible for (and ultimately held accountable for) national rather than global developments, the global perspective is not well represented politically. This presents a major challenge to the process of globalisation.

Figure 5a Cross-country inequality to continue declining...

Figure 5b ...while within-country inequality remains high

Note: Global Lorenz Curve - closer to the 45-degree line implies less inequality (top panel); GINI coefficients for major economies (bottom panel).

Source: GS (2022), World Bank

Key long-term risks: Protectionism and climate change

Of the many risks to our projections, we view two as particularly important for world growth and income convergence.

- First is the risk that populist nationalism leads to increased protectionism and a reversal of globalisation. Populist nationalists have gained power in several countries, and the supply chain disruptions during the Covid pandemic have resulted in an increased focus on on-shoring and supply chain resilience. At least to date, this has led to a slowdown rather than a reversal of globalisation, in our assessment. However, the risk of a reversal is clear. Globalisation has been a powerful force in reducing income inequality across countries. But to ensure that it continues, greater efforts need to be made for sharing its benefits more equally within countries.

- Second is the risk of environmental catastrophe is presented by climate change. We reject the view that economic growth and environmental sustainability are incompatible – many countries have been able to ‘decouple’ economic growth from carbon emissions, so there is no practical reason why this should not be achievable for the global economy as a whole. But achieving sustainable growth requires economic sacrifices and a globally coordinated response, both of which will be politically difficult to achieve. This risk is especially relevant to the long-term economic outlook of low-income economies with geographies that are especially exposed to climate change. With limited financial means to protect themselves against the costs of climate change, out-migration from these economies could dampen the demographic shifts that are projected to drive GDP growth.

References

Barro, R and X Sala-i-Martin (1992), “Convergence”, Journal of Political Economy 100 (2): 223-251.

Daly, K and T Gedminas (2022), “The Path to 2075 — Slower Global Growth, But Convergence Remains Intact”, GS Global Economics Paper, 6 December.

O’Neill, J (2001), “Building Better Global Economic BRICs”, GS Global Economics Paper, 30 November.

Wilson, D and R Purushothaman (2003), “Dreaming with BRICs: The Path to 2050”, GS Global Economics Paper, 1 October.

Wilson, D, K Trivedi, S Carlson and J Ursúa (2011), “The BRICs 10 Years On: Halfway Through the Great Transformation”, GS Global Economics Paper, 7 December.