We stress the need for sustainable public finances, sound monetary policy, a predictable and fair regulatory framework, and flexible labour markets. An overarching objective of these policies is to deliver a stable macroeconomic environment that can facilitate the flow of resources to the most efficient uses and to lay foundations for a durable economic growth, the success of human capital development, attracting foreign direct investment, technological leapfrogging, and many other elements of reconstruction (see Gorodnichenko et al. 2022 for more details).

Even with significant foreign aid for post-war Ukraine and access to (income from) Russian assets currently frozen in the West, public finances will be strained by limited tax revenues (the economy has shrunk, the labour force is reduced, the ability to raise taxes without hurting the economy is limited) and large spending demands to cover basic public services, social support, and rebuilding needs. One may expect significant fiscal deficits in the early post-war period, although not as large as the current deficit of 30% of GDP. To mobilise revenues, the government should ask for a deep debt relief, close loopholes, broaden the tax base, minimise quasi-fiscal risks from state-owned enterprises, and privatise these enterprises. On the spending side, the government should focus on developing more targeted aid, consolidating services, reforming the pension system, avoiding credit interventions, and minimising tax breaks, special zones, and other forms of tax expenditures. We also advise establishing a fiscal council, furthering the decentralisation reform with shifting more resources and powers to the local governments, and continuing the digitalisation of government services.

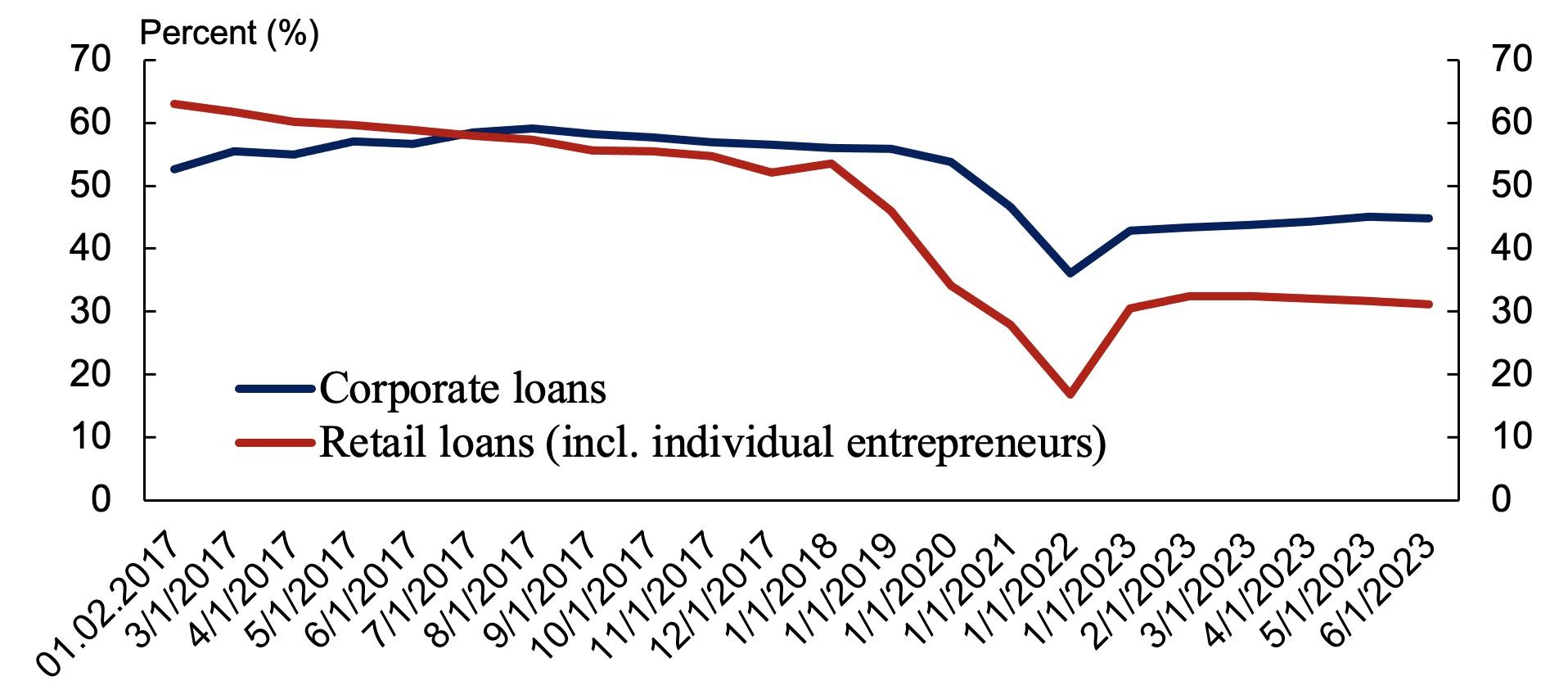

Monetary policy should return to inflation targeting with a managed floating exchange rate. Non-performing loans (approximately 40% of portfolio; see Figure 1) should be collected in a publicly owned ‘bad bank’ so that the thoroughly cleaned and re-capitalised banks can effectively allocate credit in the economy. To minimise the chance of boom-bust dynamics in the post-war economy and risks associated with the banking system weakened by the war, we advise using capital controls and macroprudential tools to contain potentially excessive growth of credit, speculative capital flows, potential dollarisation of the economy, and vulnerabilities of the concentrated banking sector. Some financial repression may be inevitable but there are better options to address post-war challenges. Finally, the National Bank of Ukraine should not serve as a source of funding for the government or as a development bank to facilitate the recovery.

Figure 1 Share of non-performing loans in the banking sector

Source: National Bank of Ukraine

Labour market policies should switch from the approach that emphasises the protection of jobs to the approach that focuses on providing insurance. The latter will help facilitate enormous post-war adjustment across space, sectors, and skills in the labour market. To reduce mismatches, this approach should be supported with remedial education and training, which can be funded with donor aid and backed with their technical assistance. With looming demographic challenges, it is critical to encourage labour force participation by allowing flexible forms of employment, stronger connection between social benefits and earnings, subsidised childcare, and related policies. Migration can help close workforce shortages.

The main goal for the regulatory framework is to provide a fair and predictable environment. With an eye to eventual adoption of EU regulations, Ukraine should conduct a comprehensive audit of current regulations and use regulatory impact assessment for weighing costs and benefits of future regulation. Although some efficiency gains can be achieved quickly (e.g. by accepting EU licenses), other areas (e.g. anti-trust regulation) require deep reforms to grow domestic institutions rather than outsource them.

A difficult road lies ahead of Ukraine, presenting many risks. Foreign aid could be poorly coordinated or not materialise, security issues may be not resolved completely, policies could take a populist turn, refugees may not return. However, only Ukraine can accomplish its homework and transform itself into a modern country with robust, democratic institutions and a dynamic economy. The international community has offered Ukraine unwavering support during the war and for the post-war period. The determination of Ukraine and its partners gives us reasons to believe that Ukraine’s rebuilding will be a success story. We hope that this report will contribute to this success.

References

Becker, T, B Eichengreen, Y Gorodnichenko, S Guriev, S Johnson, T Mylovanov, M Obstfeld, K Rogoff and B Weder di Mauro (2023), “Postwar macroeconomic framework for Ukraine”, CEPR Rapid Policy Response #3.

Gorodnichenko, Y, I Sologoub and B Weder di Mauro (2022), Rebuilding Ukraine: Principles and Policies, CEPR Press.

Kyiv International Institute of Sociology (KIIS) (2023), “How many Ukrainians have close relatives and friends who were injured / killed by the Russian invasion: results of a telephone survey conducted on May 26 - June 5, 2023”, 29 June.

Kyiv School of Economics (2023), Report on Damages to Infrastructure, March.

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (2023), “Ukraine Emergency”.