Editors' note: This column is part of the Vox debate on "Lessons from Recent Stress in the Financial System"

Financial markets experienced several events of severe financial instability during 2022–2023. Post-Covid-19 inflation, combined with the Russian aggression and an energy war, put pressure on interest rates to rise. This shock caused a wave of financial instability in the banking and derivatives markets. In a recent paper (Löyttyniemi 2023), I summarise the key events during this period.

In this column, I will analyse the public intervention or backstop mechanisms that were used in response to the crisis events. First, I shall review the recent work on public interventions in banking crises, and then I will look at the intervention measures taken recently.

Financial instability is a real or expected threat to financial markets or financial institutions due to an event, which could potentially – if public authorities do not intervene – lead to problems. Public decision makers and authorities know that financial crises are costly and also that they may be self-fulfilling. There is therefore an incentive to act promptly, decisively, and with sufficient power to tame an evolving crisis. Based on a large wealth of empirical academic work on banking crises, one could conclude that they are typically related to previous credit booms. Interventions to avoid a banking crisis can be motivated by the enormous economic costs associated with the crises in the form of lost GDP. However, the costs of intervention are also high. Some of these costs may incur losses, while some may be ‘only’ liquidity arrangements that will be paid back. The easiest interventions are guarantees, which could entail no costs or liquidity needs from governments or from central banks.

Metrick and Schmelzing (2021) analyse banking crisis interventions during the period 1257 to 2019. They classify the interventions into seven main categories and 20 types. The seven main categories are: ‘lending’, ‘guarantees’, ‘capital injections’, ‘asset management’, ‘restructuring,’ ‘rules’, and ‘other’. The authors identify a total of 1,886 interventions spread over 902 crises across 128 countries, and conclude that there has been a gradual shift over the centuries from traditional interventions by a lender of last resort, suspensions of convertibility, and bank holidays towards a much more prominent role for capital injections and sweeping guarantees of bank liabilities. They also find that the frequency and size of global interventions have gradually been rising since the late-17th century. They conclude that, over time, governments have become more aggressive in their interventions and moved down the balance sheet from liabilities to equity, and that more combinations of various tools have been used. They define a bailout as an arrangement in which some expected wealth was transferred from taxpayers to bank stakeholders.

In a later paper, Metrick and Schmelzing (2023) compare the bank intervention measures used in March 2023 to their long-term database of similar crises over the last eight centuries. ‘Lending’ is the most widely used intervention measure in banking crises in their 2021 database. They look at how unusual the combination of account guarantees and emergency lending interventions, as deployed in March 2023, is. Using the large database, they find that a total of 57 banking crises, or 6.5% of all crises, exhibit such a combination over time. It is therefore a relatively rare occurrence to see such a policy mix being deployed. They also find that the vast majority of events with the same pattern of interventions as seen in March 2023 ultimately evolved into episodes of systemic bank distress.

Admati et al. (2023) analyse the Credit Suisse event. They argue that it illustrates the failure of post-2008 attempts to eliminate the ‘too big to fail’ problem and call for more equity capital in banking. Brunetti (2023), among others, also raises concerns about the resolution of large financial entities and calls for further development in global regulation. Dewatripont et al. (2023) suggest improving the current resolution framework in the EU and extending the protection of short-term deposits for large and small companies for their ordinary business.

Analysis of the public backstops

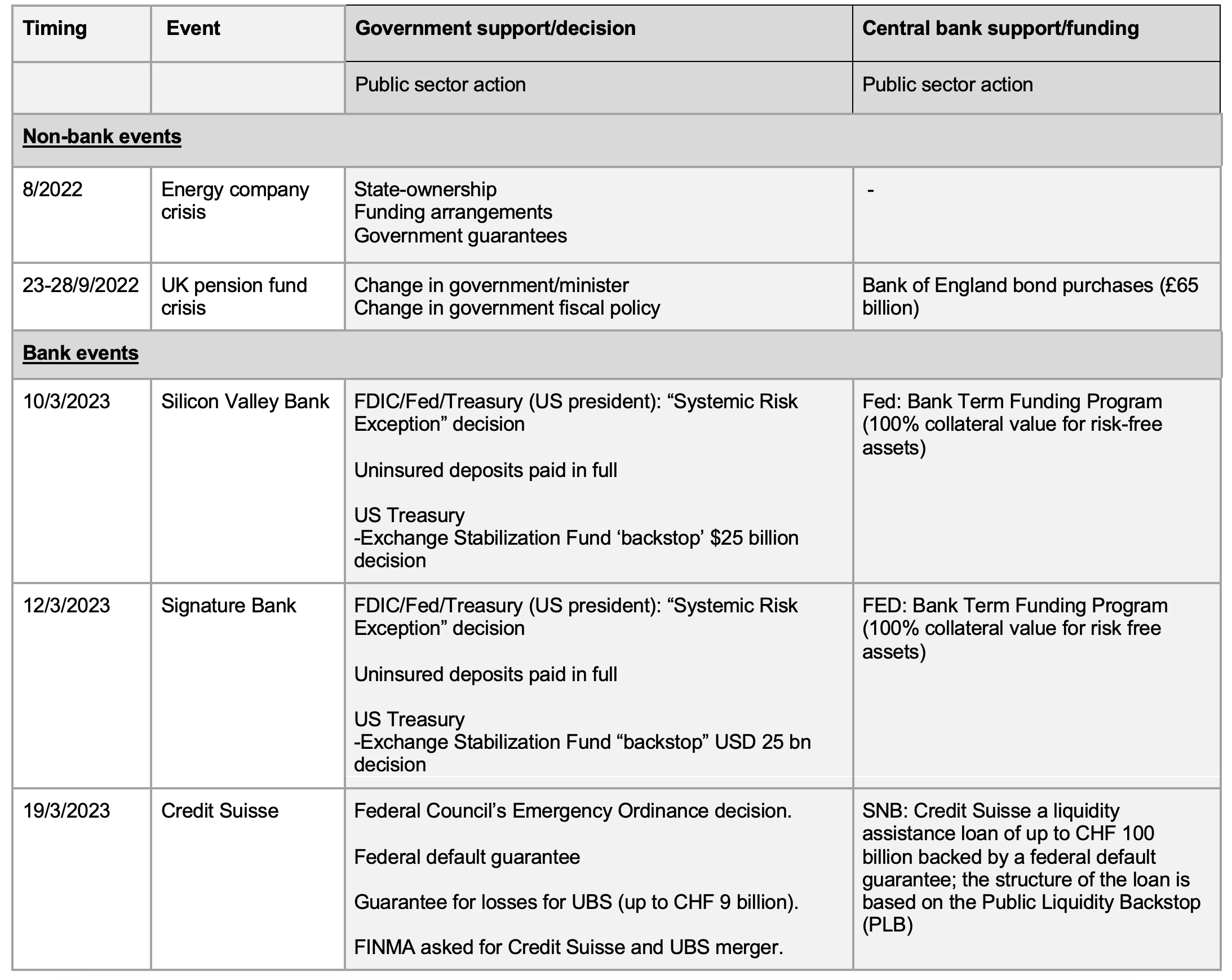

In times of financial stress, the public sector may be the only provider of a backstop to avoid financial instability causing economic damage. There were two European crises in August/September 2022 and at least three individual bank crises where backstops were used extensively. Table 1 provides a summary of the key non-bank and banking events (up to May 2023), and together with Table 2 it provides insights into the various public backstops used during those events. The actions and interventions listed below go beyond what resolution authorities are entitled to. Interventions and backstop are either pre-planned or designed ad hoc for the specific event.

Table 1 Selected financial instability events and public sector backstops in 2022-2023

Note: Information is based on press releases at the time of the event.

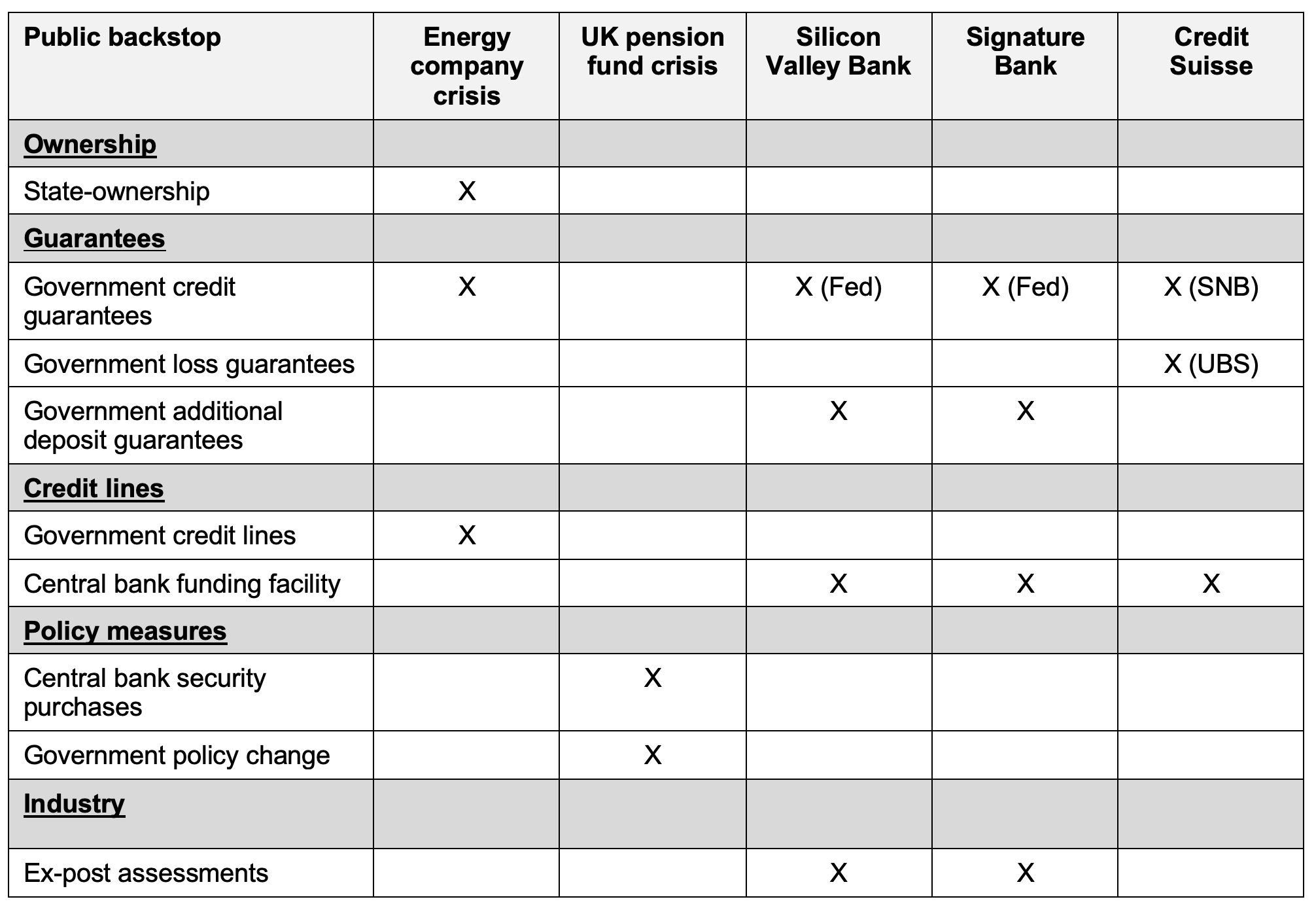

These ‘backstop’ procedures can be categorised as:

- state ownership

- state credit guarantees

- state loss guarantees

- state deposit guarantees

- state credit lines

- change in government policy (immediate)

- central bank funding facility

- central bank security purchases, including quantitative easing (immediate)

These backstop measures are mapped to the selected crises in Table 2. Most relate to banking institutions, while two of the crises are different in nature but could still have impacted important corporations, central counterparties in derivatives markets, financial institutions, and the economy in general if the public sector had not reacted quickly to systemic vulnerabilities.

Table 2 Mapping the public backstops used during selected crises in 2022-2023

Note: Evaluation is based on press releases at the time of the event.

Backstops are defined here as measures that go beyond juridical resolution or supervisory work and where the public sector needed to take extraordinary measures beyond their normal duties to safeguard the financial system. Backstops are typically created by the government or central bank. In addition, supervisors and resolution authorities may issue decisions that can have implications for financial institutions.

The lender of last resort role has been played either by the central bank or the government, depending on their natural role in the particular crisis. Typically, the central bank is the lender of last resort for financial institutions, while for non-bank or non-financial institutions the government may play that role.

In two of the crises, ex-post assessments (i.e. contributions) from the relevant industry were part of the solution to recover potential losses in the resolution, according to press releases published by the authorities. This comes under Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) procedures in the US, as well as part of the Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive (BRRD) and Single Resolution Mechanism (SRM) procedures in Europe.

Conclusions

Though the events of non-bank and banking financial instability of 2022-2023 are independent phenomena, they are connected by energy prices, inflation, interest rates, and the general sensitivity of financial markets. Various public sector backstop tools were used during these episodes: state ownership, guarantees, credit lines, loss guarantees, and central bank funding arrangements. The ‘energy company crisis’ affected some energy companies and derivatives markets, and governments needed to act to restore financial stability. In one case – the ‘UK pension fund crisis’ – a clear policy mistake was made by the government, causing it to alter course and the central bank to mitigate the mistake through purchases of long-term government bonds. Backstops were used in two regional bank events in the US and in the case of Credit Suisse. The current frameworks in the euro area and in the US ensure that if losses incur, these will be borne by the industry, and this was clearly stated in the US statements by the FDIC.

To summarise:

- One non-bank financial instability event (the ‘energy company crisis’) required government interventions, including guarantees and liquidity, as the government – not the central bank – was the available lender of last resort.

- One non-bank financial instability event (the ‘UK pension fund crisis’) required a change in government policy and an intervention by the central bank to combat rising interest rates. The intervention tools used were thus policy changes.

- In the bank crises, resolution frameworks provided the basic structure for action by the authorities but not the full solution to the larger crises. Bank events required tools from governments and central banks beyond resolution frameworks. Industry-financed assessments (i.e. contributions) were not sufficient to cover backstop needs in the US.

- Each of the non-bank and bank interventions by public sector authorities, governments and central banks was sizable, timely, and resolved the imminent threat of financial instability.

These selected crisis events demonstrate that public backstops may be needed in times of financial instability to restore market confidence. Further work needs to be done on why these crises took place and what should be done to avoid such large events of potential instability in future. Derivatives market central counterparties (CCPs) become more important after over-the-counter (OTC) derivatives have been transformed to exchange-traded derivatives markets. Vulnerabilities in banking may not have been addressed sufficiently, and further work needs to be done regarding these inherent vulnerabilities. The two US cases demonstrate the need to assess the status of large uninsured deposits. In addition, resolution frameworks need to be developed further to incorporate and integrate public backstop procedures, although the financial market architecture should be designed without these.

References

Admati, A, M Hellwig and R Portes (2023), “Credit Suisse: Too big to manage, too big to resolve, or simply too big?”, VoxEU.org, 8 May.

Brunetti, A (2023), “Big banks must become globally resolvable – or significantly ‘smaller’”, VoxEU.org, 1 May.

Dewatripont, M, P Praet, and A Sapir (2023), “The Silicon Valley Bank collapse: Prudential regulation lessons for Europe and the world”, VoxEU.org, 20 March.

Löyttyniemi, T (2023), “Financial instability and public backstops during 2022-2023”, mimeo, June (see also the Vox column here).

Metrick, A and P Schmelzing (2021), “Banking-crisis interventions 1257-2019”, available at SSRN.

Metrick, A and P Schmelzing (2023), “The March 2023 bank interventions in long-run context – Silicon Valley and beyond”, Economics Working Paper 23107, Hoover Institution.