The recent surge in migration to Europe has brought new attention to economic research on sudden refugee inflows of the past. Previously, Card (1990) found that a large inflow of Cubans to Miami in 1980 did not affect native wages or unemployment. Hunt (1992) found that a large inflow from Algeria to France after independence in 1962 caused a small increase in native unemployment. Friedberg (2001) found that a large inflow of post-Soviet Jews to Israel between 1990 and 1994 did not reduce native wages. Angrist and Kugler (2003) found that a surge of Balkan refugees during the 1990s was associated with higher native unemployment in 18 European countries, but do not interpret the association as causal because it was unstable and statistically insignificant.

Recent studies have challenged these results by re-analysing all four of these refugee waves. This new wave of research claims that earlier work obscured uniformly large, detrimental effects, either by aggregating the affected workers with unaffected workers (Borjas 2017) or through inadequate causal identification (Borjas and Monras 2017), or both.

In a recent paper, we reconsider the published research on refugee inflows to reconcile the new results with the old ones (Clemens and Hunt 2017). We find that, for all four refugee waves, the methods used in the recent re-analyses were subject to substantial bias. Correcting these biases largely eliminates the disagreement between the new and old findings – that is, corrected methods offer strong evidence of small detrimental effects in 1962 France, weak evidence of detrimental effects in 1990s Europe, and no clear evidence of detrimental effects in 1980s Miami or 1990s Israel.

Blunt instruments

The new research on these refugee waves uses instrumental variables to separate correlation from causation, and this is its biggest problem. The simple association between natives’ labour market outcomes and migrant inflows across regions or occupations could arise not from migrants’ effects, but from their choice of where to go. Migrants are likely to choose high-wage areas or occupations, which could mask any negative causal effect they have on native wages. The new research tries to account for this by using prior migration flows as an instrumental variable. This tests the effects of migration that was determined by prior immigration patterns – the instrumental variable – rather than recent economic changes.

But there's a problem when the instrumental variable (in this case, past migration per population) and the variable affected by migrants’ choice of location or occupation (current migration per population) both have the same denominator (Bazzi and Clemens 2013). Of course, the instrumental variable strategy works only when the two variables are strongly correlated, but any two variables will be strongly correlated if they share the same divisor. Indeed, even random noise will be correlated with a variable of economic interest if both are divided by the same quantity. If a random, ‘placebo’ instrument gives similar results in any instrumental variables study, it implies that the original instrument was doing little work to separate correlation from causation. We show that repeating Borjas and Monras’ (2017) re-analysis of refugee waves with a placebo instrument – random noise divided by population – gives similar results to the original studies. In most cases, the results are actually stronger using this meaningless placebo: the estimates of detrimental effects on natives are a bit larger and more statistically significant.

Kronmal (1993) suggested a simple specification correction to address this problem: rather than divide past migrant flows and current migration flows by population, use past migrant flows alone as an instrument for current migrant flows alone – while controlling for population. When we make this specification correction, none of the results in Borjas and Monras (2017) differs substantially from the original studies of migration in Miami, France, Israel, and Europe.

Shifting composition of survey data subgroups

In re-analysis of one of the four episodes, the 1980 wave of Cubans into Miami known as the 'Mariel boatlift', there is a special problem. Though Borjas and Monras (2017) agreed with Card (1990) that the Mariel boatlift did not affect unemployment for native workers, Borjas (2017) has argued that Card’s analysis missed large detrimental effects on wages. Card’s analysis aggregated all workers with a high school education or less, and found no wage effects. Borjas separated out male non-Hispanic workers with less than a high school education, and found a very large and robust fall in average wages for that group in Miami relative to comparison cities after 1980.

Our re-analysis points out a previously unreported problem with the method used by Borjas (2017). The result is highly sensitive to selecting different subsets of workers to study (see Figure 8 in Peri and Yasenov 2017), but why this is so has been unclear. Among the subsamples of non-Hispanic men with less than a high school education that Borjas studied, the fraction that were black is much higher after the boatlift than before it in Miami, but not in the comparison cities. This could not have been caused by Cubans arriving in Miami, because the sample excluded Hispanics. It is likely that it reflected the large and simultaneous arrival of low-income Haitians with less than a high school education (who could not be separated from US workers in the data), and contemporaneous efforts of the Census Bureau to improve its coverage of low-income black men.

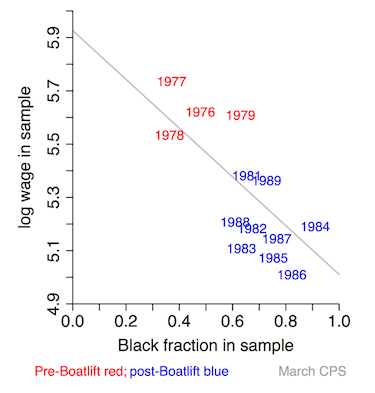

Because Haitian blacks earned much less than US blacks, and US black men earned much less than non-black men at this education level, this compositional change would mechanically cause a large, spurious fall in the average wage in the sample. It is enough to explain the entire post-boatlift fall in wages that Borjas (2017) found. Figure 1 shows the jump in the share of blacks at the time of the boatlift (seen by comparing years plotted in red with those plotted in blue) and the strong correlation in Miami between the share of blacks and the average wage.

Figure 1 Miami: Workers with less than a high school education

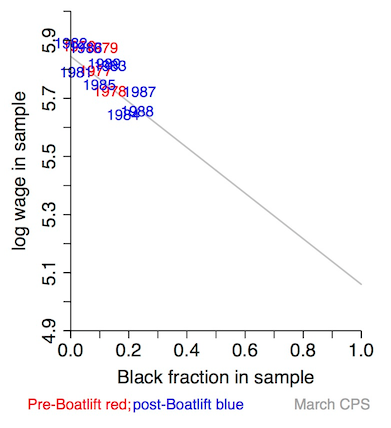

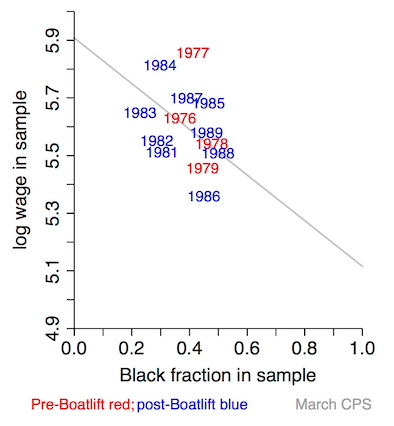

The fraction of blacks in the sample and wages are also strongly negatively correlated in the comparison cities that Borjas selected (Figure 2), and in an otherwise comparable sample of Miami workers with a high school education (Figure 3). But because the fraction of blacks did not rise at the time of the boatlift for men with less than a high school education in control cities, nor for men in Miami with a high school education only, there was no decline in wages at this time.

Figure 2 Control: Less than a high school education

Figure 3 Miami: High school education only

This is prima facie evidence that a substantial portion of the post-1980 fall in Miami wages was spuriously attributed to the Cuban refugee inflow in Borjas (2017). But it does not establish what portion of the effect that Borjas measured was spurious. When estimates of the impact of the boatlift are adjusted to account for the change in racial composition in the sample, and when the effect of race on wages is allowed to differ by city, the effect found by Borjas is attenuated by more than 50%, and its statistical significance becomes fragile to the choice of dataset and choice of control cities.

A further adjustment recognising that the effect of race on wages differs by education level means the effect is statistically insignificant. The corrected regressions cannot rule out a wage effect of -2% to -8% relative to the Borjas control cities – much smaller than the -45% effect measured by Borjas in the corresponding regressions – but they cannot rule out a zero effect either.

No support for large detrimental effects

The evidence from refugee waves shows detrimental short-term effects on labour market outcomes for native workers in some times and places, but no effect in others. It supports the consensus that the impact of immigration on average native-born workers has been small (Blau and Mackie 2016). It does not support claims of large detrimental impacts on workers with less than high school education.

References

Angrist, J D and A D Kugler (2003), “Protective or counter-productive? Labour market institutions and the effect of immigration on EU natives,” Economic Journal 113 (488): F302–F331.

Bazzi, S and M A Clemens (2013), “Blunt instruments: avoiding common pitfalls in identifying the causes of economic growth,” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 5 (2): 152–186.

Blau, F D and C Mackie (eds) (2016), The Economic and Fiscal Consequences of Immigration, Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Borjas, G J and J Monras (2017), “The Labor Market Consequences of Refugee Supply Shocks,” Economic Policy, forthcoming.

Borjas, G J (2017), “The Wage Impact of the Marielitos: A Reappraisal,” ILR Review, forthcoming.

Card, D (1990), “The impact of the Mariel boatlift on the Miami labor market,” ILR Review 43 (2): 245–257.

Clemens, M A and J Hunt (2017), “The Labor Market Effects of Refugee Waves: Reconciling Conflicting Results”, CEP Discussion Paper No. 1491.

Friedberg, R M (2001), “The impact of mass migration on the Israeli labor market,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116 (4): 1373–1408.

Hunt, J (1992), “The impact of the 1962 repatriates from Algeria on the French labor market,” ILR Review, 45 (3): 556–572.

Kronmal, R A (1993), “Spurious correlation and the fallacy of the ratio standard revisited,” Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series A 156 (3): 379–392.

Peri, G and V Yasenov (2017), “The Labor Market Effects of a Refugee Wave: Applying the Synthetic Control Method to the Mariel Boatlift,” NBER Working Paper 21801.