In 2018, the US unilaterally imposed tariffs of between 10% and 50% on imports from several countries and across a variety of goods (Fajgelbaum et al. 2019). This marked a significant departure from the previous 75 years of trade policymaking, which had relied on a rules-based, multilateral system of reciprocity to obtain persistently low tariffs. This return to protectionism is echoed in the current Biden administration, where the tariffs on China remain in place, the WTO remains hamstrung, and there is an explicit move to industrial policy in the US, with the surge of subsidies for favoured industries. Both political parties appear to have converged on a policy shift towards protectionism, in contrast to most of the history of US trade policy (Irwin 2017), where the Democratic or Republican parties have stood in opposition to the tariff. In a recent paper, we explore this bipartisan retreat from reciprocal trade liberalisation, as well as other major transitions in US trade policy since the Civil War (Bowen et al. 2023).

Unlike the standard view, which is elegantly captured in the ‘Protection for Sale’ model by Grossman and Helpman (1994), we incorporate domestic bargaining between political parties, transfers, and reciprocity. This model of political bargaining between two parties supplements a standard two-good, two-factor, two-country trade model, and offers a foundation for understanding 160 years of US trade policy.

It has as its primitives the status quo domestic tariff and transfer levels, the interests of the agenda-setting party, and economic conditions abroad (the foreign tariff and the size of the foreign export sector). Political conditions determine the identity and interests of the agenda setter, and any offer the agenda setter makes to the rival political party must be no worse (for either party) than that available under the status quo tariffs and transfers. While this status quo bias leads to long periods of policy stability, significant political and economic shifts can be large enough to fundamentally change trade policy outcomes.

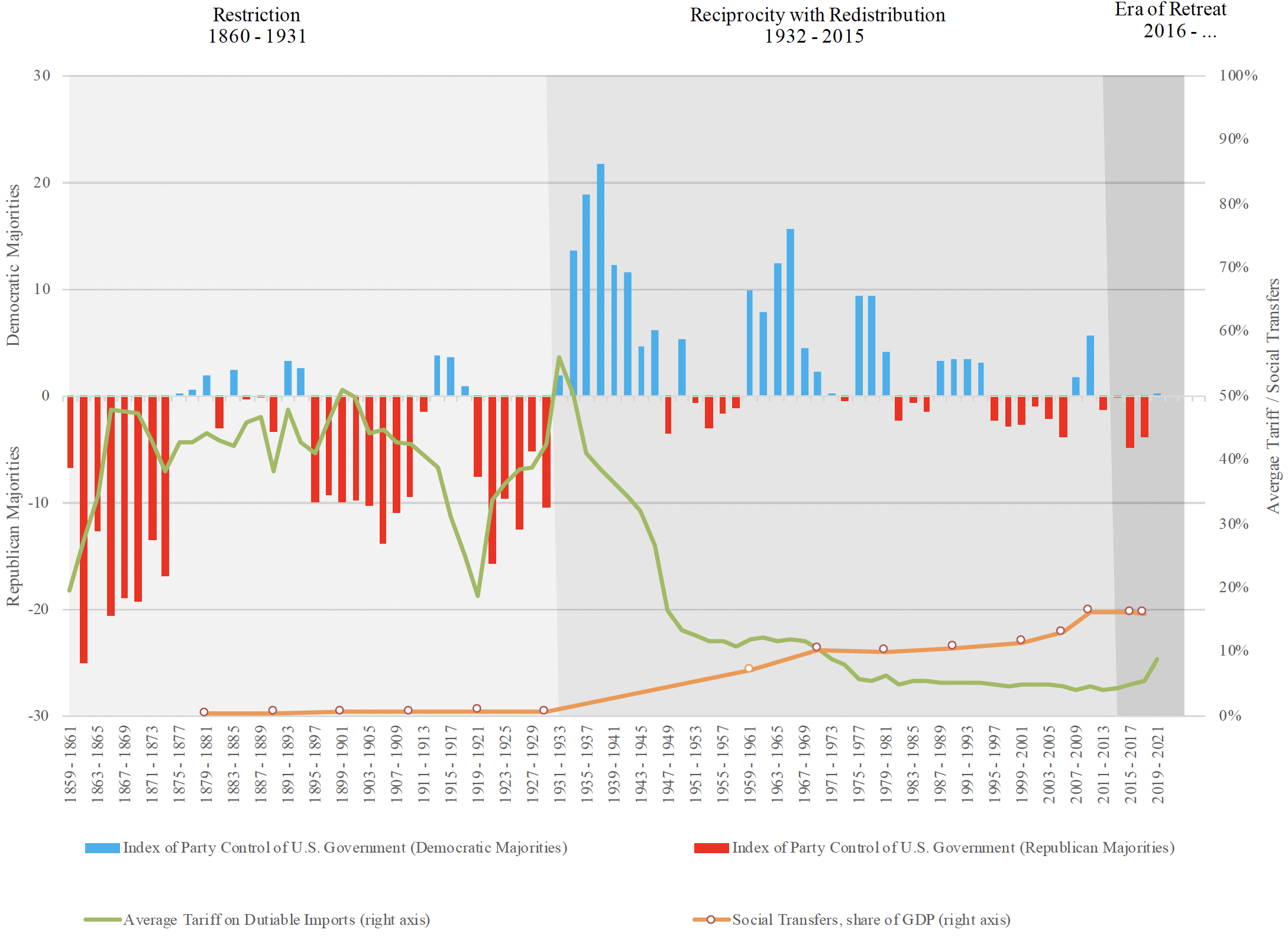

The history of US trade policy has featured two major political parties taking opposite stands on trade, one party representing the globalists and the other, the protectionists. At times the Republican Party is protectionist; at other, globalist. The same is true of the Democratic Party. Figure 1 plots an index of party control with red and blue bars (Lee 2016), and the evolution of average tariffs on dutiable imports in the US in green from 1859 to 2021. The index of party control is the average of the Democratic Party’s share of the total national popular vote for president and House and Senate seats. We subtract 50 from the average to differentiate Republican Party majorities (red bars below the zero line) from Democratic Party majorities (blue bars above the zero line).

Figure 1 US party majorities, average tariffs, and social transfers, 1859–2021

Three distinct eras of trade policy are evident in Figure 1. From the end of the Civil War to the Great Crash of 1929, US trade policy was characterised by relatively high tariffs; like Irwin (2020), we describe this as the Era of Restriction. As the red bars in this first era indicate, the Republican Party, representing the import-competing North, held agenda-setting authority. Prior to the Civil War, the tariff was low, and was not a major source of revenue; postbellum, the protectionist northern Republicans proposed a higher tariff, which was agreed to by the southern and western Democrats motivated by sharing in the tariff revenues. Consistent with our model, political bargaining across parties with divergent interests, given a status quo of low foreign tariffs and protectionism at home, resulted in unilateral protectionism. The usual terms-of-trade arguments led to a desire for high tariffs for both globalists and protectionists. Without the need to incentivise trading partners to lower tariffs (because they are already low), unilateral protection results.

After the stock market crash of 1929 and the onset of the Great Depression, the Democratic Party swept the 1932 election and became the dominant party, as evidenced by the blue bars in Figure 1 through this period. The Democrats continue to represent export-oriented agriculture while the Republican Party still represents import-competing industries. By this time, foreign tariffs had risen dramatically in response to the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930. When foreign tariffs are high, both parties benefit from a shift to reciprocal free trade, as long as transfers to the losers from liberalisation are large enough. Figure 1 shows a dramatic drop in the average tariff during the period we label the Era of Reciprocity with Redistribution.

Also evident in Figure 1 is the orange line with markers, showing the rise of social transfers from effectively zero to almost 20% of GDP in this period. A striking feature of the US political economy in the 20th century is the emergence of a transformative social safety net and government investment in public assistance. Unemployment insurance, social security, a health insurance system, a public education system, and trade-related programmes such as Trade Adjustment Assistance all become part of the Reciprocity with Redistribution era. Reciprocal free trade emerges and persists when the adversely affected can be compensated; but there is no guarantee that sufficient transfers are available in a political equilibrium, especially in a globalised world. The social compact is contingent.

While Democratic Party dominance in government declines towards the end of the 20th century, and the Democrats become less committed to the liberalisation enterprise, conditions for a switch back to protectionism did not emerge. When the status quo is free trade with transfers, and as long as the transfers reach a minimum threshold, neither party would propose a shift back to protectionism. Even though Democratic commitment to free trade wanes towards the end of this period (and Republican protectionism has yet to take full effect) there is no political bargain available to either party to reverse the reciprocal liberalisation of the era. Export interests prefer to fund social transfers to the degree that keeps the import-competitors relatively indifferent to a return to protectionism.

This all changes in the first two decades of this century. Since China’s accession to the WTO in 2001, its economy has grown at an annualised rate of more than 6% per year. The US share of the world’s capital stock has declined precipitously, from above 80% at the end of World War II to less than 15% currently, while China’s share has risen to exceed that of the US. As China became relatively capital abundant, its exports of manufactured goods caused major dislocations for US manufacturers. At this time the status quo policy is free trade with transfers, and, as predicted by the theory, this can only be sustained if the transfers are large enough. The rise of China means that import-competing firms, and workers in those firms, see their welfare decline. Greater and greater transfers are required to maintain the free-trade consensus.

Figure 1 shows that transfers stagnated in this period. The Republican Party, which takes over as agenda setter in 2016, proposes a unilateral tariff – which protects declining workers and industries and reduces the transfers the globalists must pay to sustain openness. In the post-2016 Era of Retreat, stagnating transfers are associated with bipartisan agreement to raise tariffs, a consensus that continues to the current day.

Transitions between protectionism and reciprocal free trade are rare in US history because they require fundamental realignments in party politics, global economic conditions, and the status quo. Shocks like the Civil War, the Great Depression, WWII, and the rise of China disrupt party structures, the availability of transfers, and global conditions, thereby paving the way for trade-policy transitions. An important question for future research is whether it will be possible to expand transfers to the extent necessary to restore the bargain of reciprocal free trade.

References

Bowen, T R, J L Broz, and B P Rosendorff (2023), “A theory of trade policy transitions”, NBER Working Paper 31662.

Fajgelbaum P D, P Goldberg, P J Kennedy, and A K Khandelwal (2019), “The return to protectionism”, VoxEU.org, 7 November.

Grossman, G M, and E Helpman (1994), “Protection for sale”, American Economic Review 84(4): 833–50.

Irwin, D A (2017), Clashing over commerce: A history of US trade policy. Long-term factors in economic development, University of Chicago Press.

Irwin, D A (2020), “Trade policy in American economic history”, Annual Review of Economics 12: 23–44.

Lee, F E (2016), Insecure majorities: Congress and the perpetual campaign, University of Chicago Press.