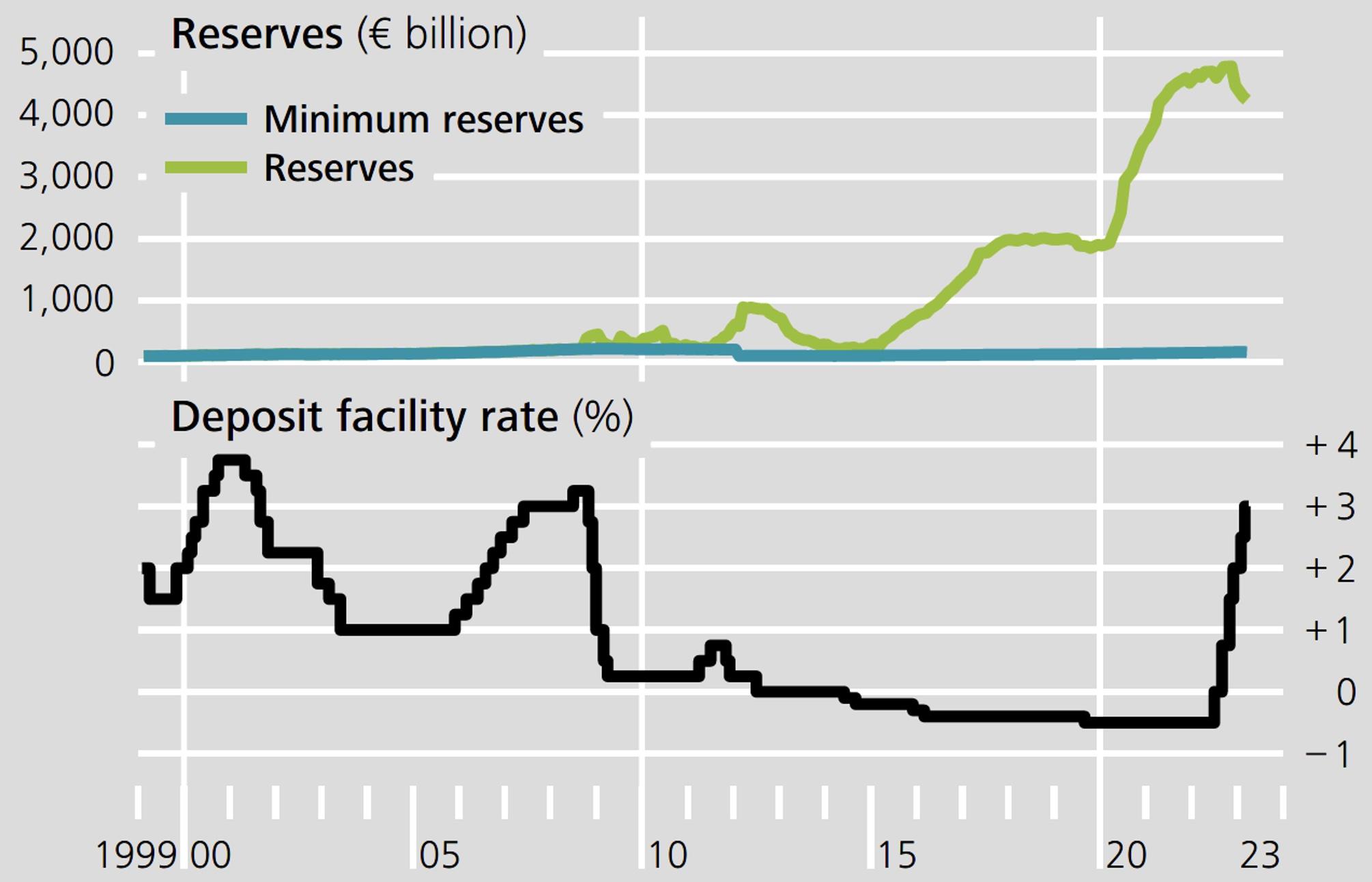

Since the second half of 2022, the Eurosystem increased key interest rates significantly to curb inflation. The deposit facility rate, i.e. the interest rate banks receive when they hold overnight deposits (reserves) with the central bank, is shown in Figure 1 (black line). When this rate became negative in 2014, banks had to pay interest on their reserves. When this rate turned positive in September 2022, banks once again earned interest income from their reserve holdings. Compared with previous tightening cycles, it is striking that banks are holding substantial reserves with the Eurosystem in the current cycle. In June 2022, that is before the onset of the tightening cycle, total reserves held by euro area banks amounted to €4.7 trillion (see the green line in Figure 1), or 12.3% of their total assets. In 2008, this figure was only €0.1 trillion, or 0.75% of their total assets. This increase was driven, in particular, by non-standard monetary policy measures, such as the asset purchase programmes in the context of quantitative easing.

Central bank reserves are special in that they are the safest and the most liquid assets available. Central banks largely determine the aggregate level of reserves, and unlike other assets, central bank reserves can only be held by banks - the traditional counterparties of central banks.

Figure 1 Central bank reserves and deposit facility rate

Source: Deutsche Bundesbank

What impact could reserves have on bank lending?

In conjunction with the unprecedentedly large reserve holdings, the interest rate hikes mean that banks with substantial reserves are earning considerable interest income from their reserve holdings for the first time in the history of the Eurosystem (e.g. De Grauwe and Ji 2023). Taken in isolation, this could affect the balance sheet channel of monetary policy transmission, the standard transmission channel of monetary policy (e.g. Bernanke and Gertler 1989, Bernanke 2007, Brunnermeier and Sanikov 2014). In this context, monetary policy affects banks’ lending decisions via their net worth. Due to banks’ maturity transformation interest rate increases (in an environment without substantial reserves) typically affect the market value of banks’ assets more strongly than their liabilities, thus reducing banks’ net worth. This can dampen their credit supply, in particular for banks with low capital ratios.

In an environment with substantial reserves, however, the revaluation of bank assets could have a less significant impact on banks with a higher reserve ratio, as central bank reserves are, by nature, short-term assets. In addition, the cost of funding via liability-side counterparts rises less sharply if the interest rate increases are not fully passed on to bank depositors. Banks with higher reserve ratios, then earn additional interest income from holding reserves. When viewed in isolation, both effects could lead to a situation where large reserves may dampen the negative impact of monetary policy tightening on banks’ net worth and thus on credit supply. Moreover, the effect should be stronger for banks with low capital ratios, as balance sheet restrictions are more binding for these banks (e.g. Holmstrom and Tirole 1997, Jimenez et al. 2012).

Empirical evaluation of over 40 million loans confirms differences in transmission depending on the size of banks’ reserves

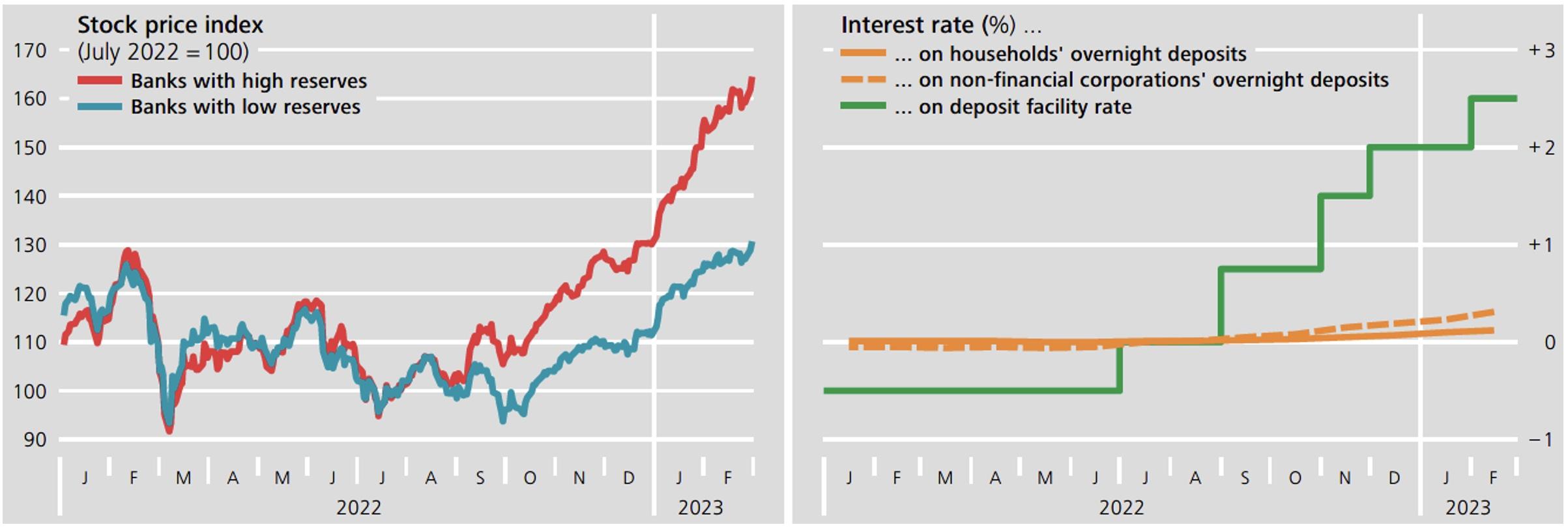

In a new study (Fricke et al. 2023), we provide empirical evidence in line with this mechanism. First, we document that banks with higher reserves experience an increase in net worth. The left-hand chart in Figure 2 shows developments in stock prices of listed banks as a proxy for net worth, distinguishing between banks with high reserves (red line) and banks with low reserves (blue line). It can be seen that the stocks of banks with substantial reserves displayed significantly higher returns after the first interest rate hike.

In addition, the right-hand chart of Figure 2 shows that banks hardly passed on the interest rate hikes to their depositors. This is relevant because deposits are the most important source of funding for banks and thus the main liability counterpart to reserves. The development of the average bank interest rates on households’ and non-financial corporations’ overnight deposits (orange lines), along with the deposit facility rate (green line), indicates that overnight deposit rates increased only slightly.

Figure 2 Stock price and deposit interest rates

Source: Deutsche Bundesbank

Consequently, the positive effect on banks’ net worth should, all other things being equal, work against potential lending restrictions. More than 40 million loans granted by banks to non-financial corporations throughout the euro area have been analysed on the basis of the AnaCredit dataset. An econometric estimate can be employed, inter alia, to separate the credit supply (the subject of the study) from credit demand (Khwaja and Mian 2008). The central finding is that the credit supply of banks with higher reserves reacts less strongly to interest rate hikes than the credit supply of other banks. The effect is more pronounced among smaller banks and banks with lower equity ratios, reaching mainly smaller enterprises and enterprises with higher credit quality. The overall effect is also economically relevant: based on the total outstanding pre-period credit volume of banks with reserve ratios above one standard deviation from the mean, this credit supply effect corresponds to 0.25% of euro area GDP in 2022. In addition, the effect is visible in the aggregate, suggesting that overall policy transmission could have been stronger in the absence of large reserve remuneration.

One might consider different options that would alter banks’ interest income from reserve remuneration. We should stress that an in-depth evaluation of the different alternatives is beyond the scope of this column. We therefore only provide examples of current policy proposals on the matter. One option could be to shrink the central bank balance sheet and reduce the amount of reserves as implemented by the Bank of England. Another approach would be to increase (unremunerated) minimum reserve requirements. Such two-tier systems for minimum reserve requirements were proposed by, for example, De Grauwe and Ji (2023).

Conclusion

Banks with high reserves recorded an increase in net worth in the wake of the ECB’s recent tightening cycle. For these banks, credit supply is less sensitive to monetary policy tightening compared to other banks, especially for banks with low capital ratios. Monetary policymakers should take these findings into account.

Authors’ note: The views expressed represent the author’s personal opinions and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Deutsche Bundesbank or the Eurosystem. A German version of this column can be found here.

References

Bernanke, B S (2007), “The Financial Accelerator and the Credit Channel”, The Credit Channel of Monetary Policy in the Twenty-first Century Conference, Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta.

Bernanke, B and M Gertler (1989), “Agency Costs, Net Worth, and Business Fluctuations”, American Economic Review 79(1): 14–31.

Brunnermeier, M K and Y Sannikov (2014), “A Macroeconomic Model with a Financial Sector”, American Economic Review 104(2): 379–421.

De Grauwe, P and Y Ji (2023), “Unremunerated Reserve Requirements Make the Fight Against Inflation Fairer and More Effective”, VoxEU.org, 7 November.

Fricke, D, S Greppmair, and K Paludkiewicz (2023), “Excess Reserves and Monetary Policy Tightening”, available on SSRN.

Holmstrom, B and J Tirole (1997), “Financial Intermediation, Loanable Funds, and the Real Sector”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 112(3): 663–691.

Jimenez, G, S Ongena, J-L Peydro, and J Saurina (2012), “Credit Supply and Monetary Policy: Identifying the Bank Balance-Sheet Channel with Loan Applications”, American Economic Review 102(5): 2301–26.

Kashyap, A K and J C Stein (1995), “The Impact of Monetary Policy on Bank Balance Sheets”, in Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy 42: 151–195.

Khwaja, A I and A Mian (2008), “Tracing the Impact of Bank Liquidity Shocks: Evidence from an Emerging Market”, American Economic Review 98(4): 1413–1442.