The global economic and financial crisis has lent new impetus to discussions of the future of the international monetary and financial system. Some advocate moving to a multipolar system in which the US dollar shares its international currency role with the euro, the Chinese renminbi and/or the IMF’s Special Drawing Rights. At the Cannes Summit of November 2011, G20 Leaders committed to taking “concrete steps” to ensure that the international monetary system reflects “the changing equilibrium and the emergence of new international currencies”.

Some observers expect this change to develop spontaneously, as a natural consequence of the declining economic and financial dominance of the US and the increasingly multipolar nature of the global economy, together with the advent of the euro and gradual internationalisation of the renminbi. Sceptics object that the prospect of a shift to a multipolar monetary and financial system is remote. If it occurs, they insist, such a transition would take many decades to complete.

The view that a shift to a multipolar system is unlikely to occur rapidly is rooted in theoretical models where international currency status is characterised by network externalities (see for example Krugman 1980 and 1984; Matsuyama et al. 1993; Zhou 1997; Hartmann 1998; and Rey 2001). These give rise to lock-in and inertia effects, which benefit the incumbent.

Such models rest, in turn, on a conventional historical narrative, epitomised by Triffin (1960), according to which it took between 30 and 70 years, depending on the aspects of economic and international currency status considered, from when the US overtook Britain as the leading economic and commercial power and when the dollar overtook sterling as the dominant international currency. Allegedly, sterling remained the dominant international currency throughout the interwar years and even for a time after the Second World War.

Recent studies (Eichengreen and Flandreau 2009 and 2010) have challenged this conventional account, showing that the dollar in fact overtook sterling already in the mid-1920s as lead currency for financing and settling trade and the leading form of international reserves. This “new view”, to paraphrase Frankel (2011), also challenges broader implications of the conventional narrative. It suggests that inertia and the advantages of incumbency are not all they are cracked up to be. It challenges the notion that there is room for only one international currency in the global system, as well as the presumption that dominance, once lost, is gone forever.

In a recent paper (Chiţu et al. 2012), we reexamine the role of international currencies as vehicles and currencies of denomination for foreign investment. Specifically, we analyse the currency denomination of foreign public debt for 33 countries in the period 1914-1946. The results lend further support to the “new view”.

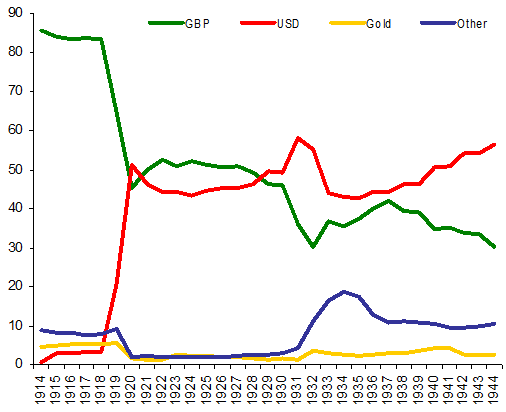

First, while network externalities, first-mover advantages and inertia matter, they do not lock in international currency status to the extent previously thought. Abstracting from the Commonwealth countries, whose allegiance to sterling was special, we show that the dollar overtook sterling already in 1929, at least 15 years prior to the date cited in previous accounts (see Figure 1). And even when the Commonwealth countries are included, we find that the dollar was already within hailing distance of sterling as a currency of denomination for international bonds by the late 1920s.

Second, our evidence challenges the presumption that monetary leadership once lost is gone forever. Although sterling lost its leadership in the 1920s, it recovered after 1933 and was again running neck and neck with the dollar at the end of the decade.

Third, our findings challenge the presumption that there is room for only one dominant international currency due to strong network externalities and economies of scope. This is true even if one takes into account the Commonwealth countries, which were heavily oriented towards sterling for institutional and political reasons.

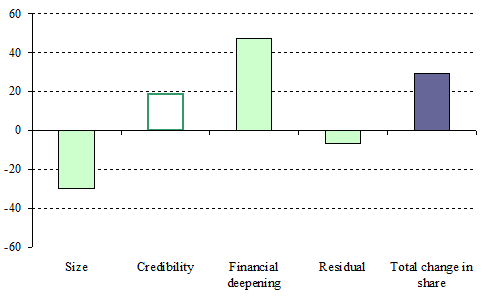

A regression analysis of the determinants of vehicle currency choice points to the development of American financial markets as the main factor that helped the dollar overcome sterling’s first-mover advantage. Financial deepening was the most important contributor to the increase in the share of the dollar in global foreign public debt between 1918 and 1932 (see Figure 2). In the case of the UK, economic stagnation, i.e., declining relative economic size, was the most important factor accounting for sterling’s declining share over the period.

These findings have important implications for the future of the international monetary system. They suggest that a shift from a unipolar dollar-based system to a multipolar system is entirely possible; that it could occur sooner than often believed; and that further financial deepening and integration will be a key determinant of the ability of currencies other than the dollar to strengthen their international currency status.

The international status of a currency will only rest on solid foundations, however, if financial deepening in the issuing country is sustainable, and not if financial innovation and liberalisation simply cause a boom that eventually goes bust. The impact of finance on international currency shares in global debt markets worked both ways in the interwar period. Our findings underscore this point as well, insofar as the collapse of the US banking system and subsequent financial retrenchment was the most important factor contributing to the decline in the share of the dollar in global foreign public debt between 1932 and 1939.

This underscores that the compass guiding the pace and scope of financial sector reform should always point to the direction of medium-term sustainability. In turn, this highlights the important role that macro-prudential policies and tools will play in shaping the international status of currencies in the new millennium.

Figure 1. Global foreign public debt – Selected currency shares (As a % of total; at current exchange rates)

Note: Estimates from Chiţu et al. (2012) based on UN (1948). The figure shows the evolution over time of the shares of sterling, US dollar, gold and other currencies in the global stock of foreign public debt (in percentage and at current exchange rates) based on a sample of 33 countries, excluding Commonwealth countries (India, Australia, Canada, New Zealand and South Africa).

Figure 2. Estimated contributions to the change in the share of the US dollar in global foreign public debt between 1918 and 1932 (in percentage points)

Note: Contributions calculated using the estimated parameters of Chiţu et al. (2012)’s benchmark model, including dynamic effects. The estimated effect of credibility is statistically insignificant.

References

Chitu, L, B Eichengreen and A Mehl (2012), “When did the dollar overtake sterling as the leading international currency? Evidence from the bond markets”, ECB Working Paper, No. 1433.

Eichengreen, B and M Flandreau (2009), “The rise and fall of the dollar (or when did the dollar replace sterling as the leading reserve currency?)”, European Review of Economic History, 13(3):377-411.

Eichengreen, B and M Flandreau (2010), “The Federal Reserve, the Bank of England and the rise of the dollar as an international currency, 1914-39”, BIS Working Papers, No. 328.

Frankel, J (2011), “Historical precedents for the internationalization of the RMB”, paper written for a workshop organized by the Council of Foreign Relations and the China Development Research Foundation.

Hartmann, P (1998), Currency competition and foreign exchange markets – The dollar, the yen and the euro, Cambridge University Press.

Krugman, P (1980), “Vehicle currencies and the structure of international exchange”, Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 12(3):513-526.

Krugman, P (1984), “The international role of the dollar: theory and prospects” in J Bilson and R Marston (ed.), Exchange Rate Theory and Practice, University of Chicago Press.

Matsuyama, K, N Kiyotaki, and A Matsui (1993), “Toward a theory of international currency”, Review of Economic Studies, 60:283-307.

Rey, H (2001), “International trade and currency exchange”, Review of Economic Studies, 68(2):443-464.

Triffin, R (1960), Gold and the dollar crisis: the future of convertibility, Yale University Press.

United Nations (1948), Public debt, 1914-1946, Department of Economic Affairs.

Zhou, R (1997), “Currency exchange in a random search model”, Review of Economic Studies, 64:289-310.