In global crises, capital tends to fly away from the countries that need it the most, as evidenced by the unprecedented flight to quality – and the resulting widening of the spreads – experienced by emerging economies in early 2020.

In this context, it is customary for political and academic leaders around the world to call for international financial institutions (IFIs) to mitigate these effects – as a group of us did here. As usual, results this time around have been disappointing: debt standstills have been, so far, underwhelming (debt relief for low-income countries never entered the discussion); plans to distribute the IMF's own Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) were vetoed by the US; and the only new IMF facility, a short-term liquidity line (SLL), was designed only for investment-grade countries. And a welcome capitalisation of the IFIs would entail a scaling up of assistance, but it would probably arrive too late and would not fix the holes in the safety net.

Paradoxically, it was the US Federal Reserve that stood out, extending its repo window (FIMA) to most central banks to stabilise the dollar and US Treasury market. However, FIMA is not intended to create liquidity – indeed, central banks could alternatively sell their Treasuries in the market – but rather to reduce volatility in the US Treasury market. The Fed would likely have no interest in adding to a country´s dollar liquidity by monetising, for example, its sovereign securities.1

There are two complementary proposals to strengthen the international financial architecture that, I believe, have not been given the consideration they deserve.

The first one is the use of the IMF as an intermediary between the Fed and other issuers of reserve currencies (the true global lenders of last resort) and countries with limited and costly access to dollar liquidity. In this arrangement, originally proposed here, the Fed would enter a swap (say, dollar for pesos) with the IMF, and the latter would enter a similar swap with the member country. Because the Fed currency swap entails no exchange risk, the new arrangement would simply leverage on the IMF´s preferred creditor status to buffer the associated credit risk.2 As in the case of FIMA, the Fed’s swap is not intended to create liquidity but to attenuate the global appreciation of the dollar – hence, its focus on advanced and emerging economies with liquid currency markets – and it is unlikely that more countries should be added to the selective list.3 The proposal was dead on arrival when presented at the IMF a few years ago, but every new crisis is a new opportunity.

A countercyclical liquidity fund

Another, complementary alternative is the creation of a special purpose vehicle (SPV) funded and managed by an IFI – an idea suggested in 2018 for the World Bank by the Group of Eminent Persons created by the G20 and which has been recently flagged, for good reasons, in the context of the pandemic.4

To illustrate when and how a SPV could create international liquidity for emerging economies, assume for the moment that it takes the form of a countercyclical liquidity fund (CLF), launched by a regional IFI such as the Latin American Reserve Fund (FLAR).

This CLF could be funded in two ways: (1) with resources from official lenders (countries and other IFIs); or (2) through the issuance of debt in voluntary capital markets.

In the first case, which essentially leverages the FLAR preferred creditor status among its members, the SPV creates international liquidity only if the contributing funds would not be otherwise available to FLAR members. It could, for example, attract capital from countries looking to have a broader exposure to a particular region, or from global IFIs that have already maxed up their own exposure to the region, or even from the IMF, if its lending capacity is constrained by stringent eligibility criteria that would be met by a well-managed investment-grade vehicle. At any rate, the CLF would be a valuable option only to the extent that it does not crowd out available sources.5

The second case is simpler: the CLF issues investment-grade bonds to fund liquidity lines and credit guarantees, partially rechannelling the abundant global liquidity in search for safe assets back to the countries it flew away from.

Why do we need a new vehicle? How is this CLF different from what the FLAR or other IFIs already do?

Case 1 does not differ much from a capitalisation or a broadening of the IFI capital structure, but has the advantage of flexibility: it may reduce bureaucratic formalities; establish specific rules on participation, use and duration of CLF products; and keep the fund open to new investments, as well as divestments, once the crisis is over.

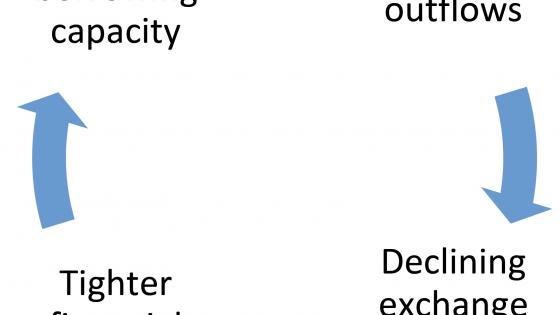

But the true advantage of this new vehicle is more visible once we move to case 2: it relates to the limitations faced by IFIs in terms of their size (leverage) and their exposure (risk diversification), as reflected in their credit ratings, to borrowing costs and lending rates. More specifically, in times of systemic crises, when international rates tend to be historically low, the CLF may go for a larger leverage ratio at the cost of a lower credit rating – always within the investment grade range – and still be able to fund itself at a cost substantially below that faced by most emerging economies. In other words, the CLF would benefit from countercyclical interest rates to make up for procyclical capital flows and credit risk spreads, thus stabilising emerging markets’ access to global liquidity.6

One could readily imagine a combined facility whereby the first tranche is funded by the parent IFI (in our example, FLAR) at a very low, AA-graded borrowing cost, and a second tranche is offered, on demand, at a moderately higher funding cost by the more leveraged, A-graded CLF – a FLAR B, as it were. In this way, the small regional IFI can scale up its assistance by leveraging its preferred credit status within the region at an acceptable cost, without compromising its hard-earned credit rating.7 Moreover, it can do so with a lean bureaucracy that could be easily wound down once the crisis and the demand for liquidity phase out.

Small is beautiful

Change in large institutions, such as the World Bank or the various regional development banks, is likely to meet internal conflict, particularly between recipient and donor members, that may delay or derail innovations such as the new, exotic junior fund with greater leverage and lower rating as the CLF proposed here.

Instead, smaller regional IFIs are ideal to lead this pioneering effort: they have the management expertise, they enjoy (regional) preferred creditor status, and their members are mostly countries on the negative side of the flight to quality and with growing needs of financial support to soothe the pandemic pain.

At the same time, a CLF would be a privileged channel through which large official creditors, including the IMF and the World Bank, could allocate a share of their unused lending capacity when and where it is most vital. In this way, the CLF may complete the financial architecture not only by providing much needed lending of last resort during systemic crises but also, more generally, as a way to attract less unstable private capital to emerging economies.

Endnotes

1 FIMA allows central banks and other international monetary authorities with New York Federal Reserve accounts to enter into repurchase agreements with the Fed. In favor of the facility, because US Treasuries remain in the central bank´s balance sheet, FIMA allows them to temporarily increase their gross (but not their net) international liquidity.

2 This facility grants the central banks access to FED dollars in exchange for an equivalent amount in local currency of the central bank that is counterpart, calculated at the market exchange rate at the time of the transaction. At the close of the trade, the amounts are exchanged again using the same exchange rate applied at the time of the transaction, so no exchange risk is involved (see also Levy Yeyati 2020). Note that there is a crucial distinction between the IMF and other IFIs that fund themselves in the capital market: to the extent that the IFI retains the credit risk, the swap would be considered as a new loan by rating agencies and thus would ultimately crowd out its existing lending capacity (for a given rating), creating no additional liquidity.

3 The possibility of facing requests from other central banks was explicitly addressed at the time the four emerging economies were added to the swap access list, and was explicitly discarded, as noted in the corresponding Fed minutes. The presence of the IMF as intermediary should allay this concern.

4 See Cárdenas (2020) and Velasco (2020).

5 For example, the initial capital injection by the founding IFI would detract from its lending capacity, with no net impact on the available liquidity.

6 Naturally, the SPV could also lend to non-financially integrated developing economies.

7 The implicit preferred creditor status of regional IFIs is reflected both in the extremely low empirical probability of default (members remain current even after outright defaults with private and official creditors) and in credit ratings that are above the best among its members.