While the latest consumer price index (CPI) figures seem to vindicate the view that inflation is here to stay, some analysts suggest that inflation expectations and unit labour costs are not increasing and thus, the inflation upsurge is transitory. On one side, Summers (2021a, 2021b) and Blanchard (2021) argue that the US fiscal stimulus plan may be inflationary, and that the increase in inflation may be permanent. On the other side, Brignone et al. (2021) show that the fiscal stimulus plan implies a moderate increase in the US CPI and, in addition, that the upside risks to inflation, broadly, are moderate. Likewise, Budianto et al. (2021) argue that inflation has picked up due to effects that are also transitory, such as base effects, bottlenecks, and the increase in energy prices. They point out that a permanent increase in price pressures requires either an increase in unit labour costs or inflation expectations, and that neither of them is taking place at present. Ball et al. (2021) use a Phillips curve defined in median inflation and concluded that the demand pressure of the fiscal plan could increase inflation “modestly and transitorily”. Likewise, for the Federal Reserve (2021), by late 2021, inflation is “largely reflecting factors that are expected to be transitory.” And last, but not least, Goodhart and Pradhan (2021) explore some of the consequences of moderate inflation, including a recession and increases in the policy rate of about 50 basis points per monetary policy meeting.

US CPI inflation reached 6.2% in October 2021. It is well known that throughout 2021, annual inflation has been distorted by base effects. Annual base effects can be corrected using biannual inflation, a measure that in October 2021 was 3.7% in annual terms. Nonetheless, annual and biannual inflation are averages of past monthly inflations; accordingly, these inflation measures do not convey the most opportune information. The most opportune indicator is monthly (seasonally adjusted) inflation, as it is the latest available information on price increases (Eurostat 2018). In October 2021, monthly inflation reached 11.9% in annual terms. Yet, monthly inflation is also distorted with base effects, monthly base effects in this case. These base effects can be corrected using bimonthly inflation. In October 2021, bimonthly inflation reached 8.5% in annual terms. Still, bimonthly inflation is not the most opportune indicator of inflation, as it is a simple average of the latest two monthly inflation rates. A more opportune indicator would strike a balance between correcting base effects and providing the more opportune information. Our preferred balance is a weighted average of current and one-month lagged monthly inflation, with weights of two-thirds and one-third, respectively.1 In October 2021, monthly inflation, partially corrected for base effects, was 9.7%.

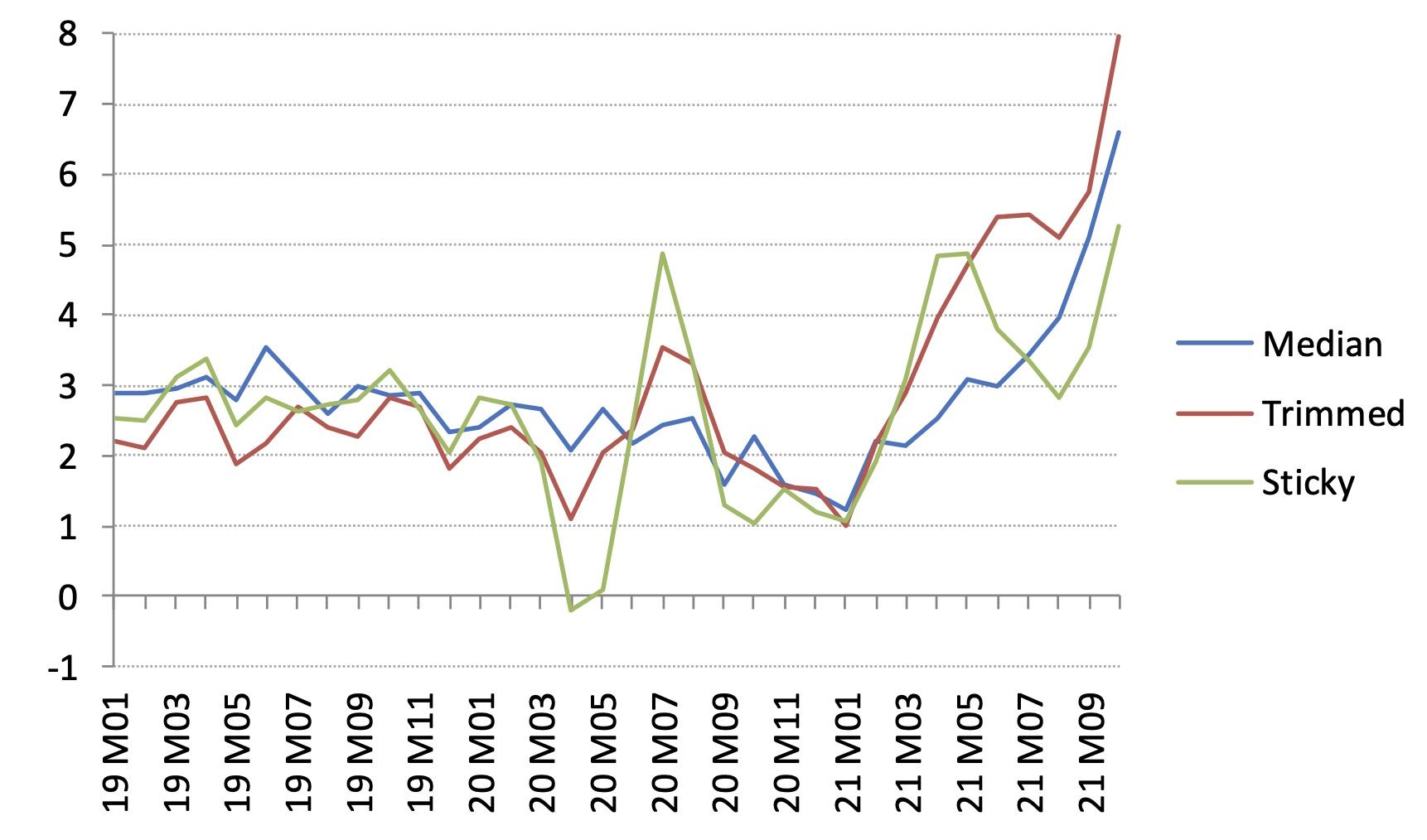

Using our preferred indicator, we now turn to core inflation. Measured by median, trimmed, or sticky-price inflation, core inflation in October 2021 escalated above and beyond 5% (Figure 1). Moreover, without annual base effects and little monthly base effects, core median and trimmed inflation are on an upward trend, while since March 2021 sticky-price inflation appears to have jumped towards about 4%.

Figure 1 US core inflation

(Monthly annualised inflation partially corrected for monthly base effects)

Note: This figure presents monthly annualised inflation which was (partially) corrected for monthly base effects.

Sources: Median and trimmed inflation from the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, sticky price inflation from the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta and authors’ calculations.

Among these measures of core inflation, sticky-price inflation has two important advantages at present. First, it can give a hint about future CPI inflation – with the caveat that uncertainty is high. Second, it can help control for the ongoing changes in the relative price of goods.2

As pointed out by Bryan and Meyer (2010) and Millard and O’Grady (2012), sticky prices can only be optimised infrequently, so price setters are typically more forward looking than those setting flexible prices. In this sense, sticky price inflation may help anticipate future CPI inflation. In addition, as shown by Aoki (2001), sticky-price inflation targeting is optimal when dealing with changes in relative prices – as is the case at present.3

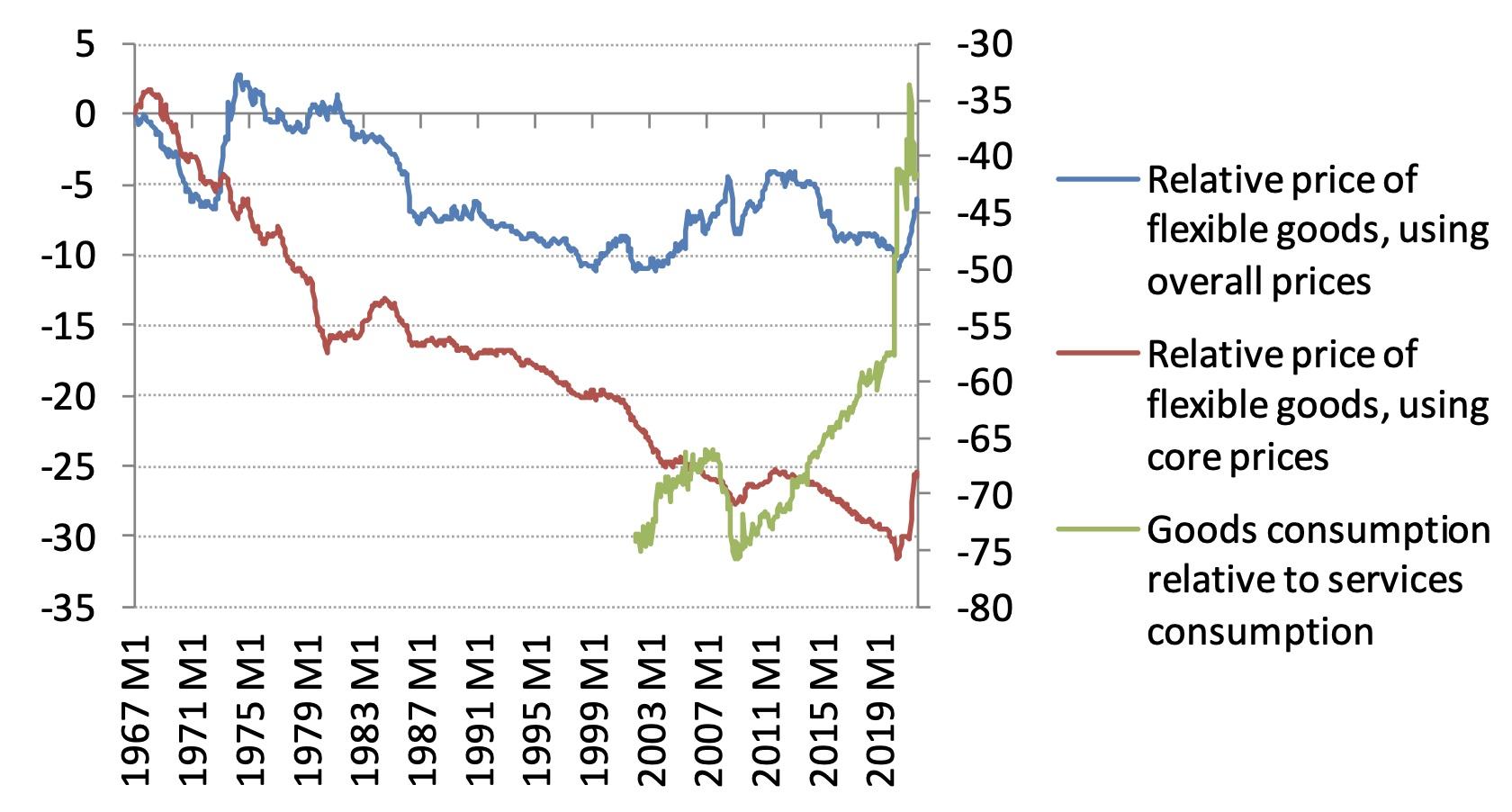

The relative price of goods surged in 2021 with the increase in the demand for goods (Figure 2). Consequently, part of the current increase in inflation derives from the change in the relative price of goods. As pointed out by Aoki (2001), the inflation measure that can set aside relative price changes is sticky-price inflation. By targeting broader measures of inflation, monetary policy unnecessarily transmits changes in relative prices to economic activity. In other words, sticky-price inflation targeting satisfies the so-called ‘divine coincidence’ put forth by Blanchard and Galí (2007) while other measures of core inflation may not.

The increase in goods prices is occurring in part because of the increase in the demand for goods and in part due to the known bottlenecks in the supply of goods.4 Interestingly, as the relative demand for services decreases, inflation in the sticky-price segment of the CPI, mostly services, does not.5 Quite the contrary, it is increasing – to 5.3% in October 2021 (Figure 1).6 In the near future, as the relative demand for goods stabilises or recedes, it is likely that further pressure on rigid-price inflation will ensue.

Figure 2 Goods’ relative prices and quantities

(Flexible-price relative to sticky price; goods consumption relative to services consumption)

Note: Goods and services prices are parallel to flexible and sticky prices; hence, the price of goods was approximated with the price of flexible-price goods and the price of services with the price of sticky-price goods. The figure shows the log of the price of flexible-price goods relative to the price of sticky-price goods and the log of the demand for goods relative to the demand for services. Sticky and flexible prices are from source Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, based on Bryan and Meyer (2010). Goods and services consumption in real terms are from Bureau of Economic Analysis, retrieved from FRED Economic Data, Federal Reserve Bank of Saint Louis.

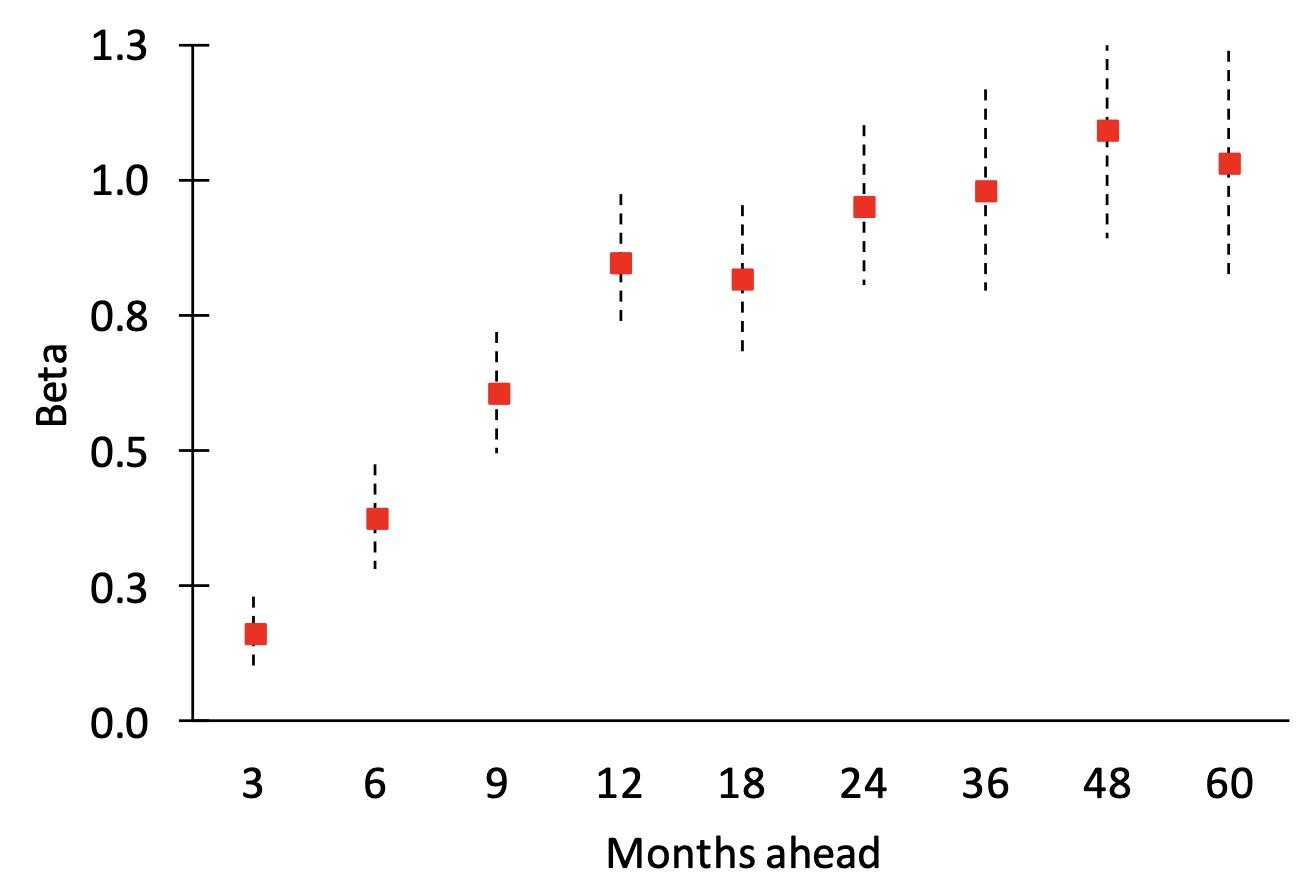

The information about future inflation that is contained in sticky-price inflation can be pinned down with a simple estimation: a regression of the future change in CPI inflation on the gap between current sticky-price inflation and CPI inflation.7 Intuitively, if the coefficient is one, the future path of CPI inflation closes the current gap between sticky-price inflation and CPI inflation; or, in other words, sticky-price inflation acts as a kind of anchor for future inflation. Figure 3 shows that sticky-price inflation anticipates CPI inflation 12 to 60 months in the future.8 Using our preferred indicator that corrects for base effects, sticky-price and CPI inflation were 5.3% and 9.7% in October 2021, respectively. Using these figures, the point forecast for annual CPI inflation in October 2022 is 5.6%. The important caveat, however, is the high amount of uncertainty in the estimation; namely, a two standard deviation for this forecast is 1.2% to 9.9%, without adjusting for upward risks.

Figure 3 Sticky-price inflation as leading indicator of CPI inflation

Note: Red squares show the estimated coefficient of a regression of the future change in inflation on the gap between sticky-price inflation and CPI inflation. The grey lines show the 95% confidence intervals.

Source: Own elaboration with data for sticky-price inflation from the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, and data for CPI inflation from US Bureau of Labor Statistics, retrieved from FRED Economic Data, Federal Reserve Bank of Saint Louis.

In conclusion, a look at sticky-price inflation is useful because it contains some information about future inflation and additionally it can set aside the ongoing changes in the relative price of goods (that is, flexible-price inflation). In this vein, a look at sticky-price inflation can protect monetary policy from targeting transitory changes in relative prices. The latest available information on sticky-price inflation, partially corrected for base effects, is 5.3% in October 2021. In turn, the CPI inflation forecast for October 2022 is 5.6% and highly uncertain.

References

Aoki, K (2001), “Optimal monetary policy responses to relative price changes”, Journal of Monetary Economics 48(1): 55–80.

Ball, L and S Mazumder (2019), “The Nonpuzzling Behavior of Median Inflation”, NBER Working Paper No. 25512.

Ball, L and S Mazumder (2020), “A Phillips curve for the euro area”, VoxEU.org, 4 February.

Ball, L, G Gopinath, D Leig, P Mitra and A Spilimbergo (2021), “US Inflation: Set for Takeoff?”, VoxEU.org, 7 May.

Beningno, P (2004), “Optimal monetary policy in a currency area”, Journal of International Economics 63(2): 293–320.

Blanchard, O (2021), “In defense of concerns over the $1.9 trillion relief plan”, Realtime Economic Issues Watch, 18 February, Washington: Peterson Institute for International Economics.

Blanchard, O and J Galí (2007), “Real Wage Rigidities and the New Keynesian Model”, Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 39(1): 35–65.

Brignone, D, A Dieppe and M Ricci (2021), “Quantifying the risks of persistently higher US inflation”, VoxEU.org, 1 November.

Bryan, M F and B Meyer (2010), “Are some prices in the CPI more forward looking than others? We think so”, Economic Commentary 2, 19 May, Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland.

Budianto, F, G Lombardo, B Mojon and D Rees (2021), “Global reflation?”, BIS Bulletin 43, Bank for International Settlements.

Erlandsen, S K (2014), “Sticky Prices and Inflation Expectations in Norway”, Staff Memo 15/2014, Norges Bank.

Eurostat (2018), Handbook on Seasonal Adjustment, 2018 edition.

Eusepi, S, B Hobijn and A Tambalotti (2011), “CONDI: A Cost-of-Nominal-Distortions Index”, American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 3(3): 53–91.

Federal Reserve (2021), “Press Release”, 3 November, Washington DC, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve.

Goodhart, C and M Pradhan (2021), “What may happen when central banks wake up to more persistent inflation?”, VoxEU.org, 25 October.

Millard, S and T O’Grady (2012), “What do sticky and flexible prices tell us”, Bank of England Working Paper 457, London.

Ress, D and P Rungcharoenkitkul (2021), “Bottlenecks: causes and macroeconomic implications”, BIS Bulletin 48, November, Basel.

Summers, L H (2021a), “The Biden stimulus is admirably ambitious. But it brings some big risks, too”, Opinion, The Washington Post, 4 February.

Summers, L H (2021b), “On inflation, it’s past time for team ‘transitory’ to stand down”, Opinion, The Washington Post, 15 November.

Endnotes

1 Note that this filter is also a one-sided exponential filter truncated at one month.

2 Other measures of core inflation have other advantages, for instance Ball and Mazumder (2019, 2020) underscore the advantages of median inflation.

3 See also Beningno (2004) and Eusepi et al. (2011).

4 On bottlenecks in the supply of goods see Ress and Rungcharoenkitkul (2021)

5 The bottom line here is that sticky-price inflation is approximately equal to services inflation while flexible-price inflation is approximately equal to goods inflation.

6 In monthly annualised terms and partially corrected for base effects.

7 Our regression for the US follows the estimation by Erlandsen (2014) for the case of Norway.

8 Data are for the US, from January 1983 to October 2021.