As we pick up the pieces from the most recent US banking crisis, many are making comparisons to the 2008-2009 collapse. But perhaps the most instructive parallels, which still hold unlearned lessons demanding attention today, are from the 1980s. The protracted unrecognised losses on securities at Silicon Valley Bank, Signature, and many others still waiting to be dealt with properly, are eerily reminiscent of the ignored losses of the 1980s, which set the stage for the banking collapses of that era.

Will the reforms enacted today be reminiscent of the ineffective reforms of 1989 and 1991, which were supposedly informed by the thrift and bank crises of the 1980s? Although those earlier statutes emphasised the need to strengthen market discipline and speed resolution of weak banks and avoid protracted unrecognised losses, the current crisis shows that they failed to do so, and those failures were compounded by the inadequacies of Dodd-Frank in 2010.

Let’s take a walk down memory lane to remember the costly collapses of the 1980s, and the consensus that emerged from them about the reforms that were needed. It’s instructive to consult the ancient scrolls and to rely on the actual words and findings of a wide range of researchers that illustrate that remarkably consistent consensus.

Between 1980 and 1994, 1,617 federally insured banks and 1,295 savings and loan institutions were either closed or received assistance from government resolution agencies (FDIC 1998, p. 4). “The reason for the plight of savings and loans at the beginning of the 1980s was a heavy concentration of assets in residential mortgage loans that had been booked at fixed rates years earlier but that were being funded with deposits paying the much higher market rates than current” (Barth 1991, p. 2). That duration mismatch, in turn, was traceable to “…federal statutes…[that]eventually led to regulations that required savings and loans to hold long-term, fixed-rate home mortgages funded by shorter-term, variable-rate deposits….[W]hen interest rates unexpectedly soared in the late 1970s and early 1980s, the savings and loan house of cards built on lending long and borrowing short collapsed” (Barth and Brumbaugh 1992a, p. xiii).

For banks, rather than thrifts, in the 1980s, other shocks were more important, such as recessionary consequences of the rise in interest rates, losses on energy lending after the 1982 oil crash, and declines in commercial real estate values after important changes in the 1986 tax law. But there were similarities between thrifts and banks in how initial losses – whatever their sources – were often magnified by the failure to address them.

“…[A]ccounting techniques…played a major role in the interaction of depositories and deposit insurance and regulation” (Barth and Brumbaugh 1992a, p. xvi). “Rather than openly disclose the size of the problem [caused by the rise in interest rates], in the early 1980s the government took actions to make it less visible” (Barth 1991, p. 3). “Does it make much sense to measure only part of the firm’s assets and liabilities accurately?... If we wish to ensure solvency of financial institutions, then we are much more concerned with errors of underestimation than overestimation” (Stiglitz 1992, p. 6).

The centrality of accounting rules in allowing delayed recognition of loss was universally recognised, including by former regulators. “…[T]he bank and thrift regulatory (and deposit insurance) regimes of the United States are based on a fundamentally flawed information system. That information system—the standard accounting framework used by banks and thrifts—looks backward at historical costs rather than at current market values. It does not yield the information that would allow regulators to protect the deposit insurance funds properly. Among the serious policy mistakes of the early 1980s were the decisions to weaken this already inadequate information system for thrifts. The revamping of this accounting framework—a switch to market value accounting—is the single most important policy reform that must be accomplished. All else pales in comparison” (White 1991, pp. 3-4).

This was widely understood at an early date, as two 1982 quotations show: “By 1982, the real capital positions of all thrift institutions had been completely eroded, and virtually all thrift institutions had large negative net worths when their assets and liabilities were valued at actual market rates. It will become increasingly apparent that many firms cannot survive unassisted.” (Pratt 1988, p. 4). “…[O]nly the accounting rules that emphasize historical costs have prevented a widespread realization of this fact” (Carron 1982, p. 84).

Academic studies showed that market valuations of assets were, not surprisingly, much better forecasters of failure than historical cost measures: “[In forecasting failures of thrifts] market value is significantly superior…to all three [book value] measures at the two-year lag, and to tangible and GAAP at the one-year lag” (Benston et al. 1992, p. 298).

There was universal agreement that the delayed recognition of loss had been a huge problem: “Accounting measures are important when explaining why the S&L situation became so serious and why it went unnoticed for so long….[F]ailure to track accurately the market value of their assets could be—and often was—catastrophic” (CBO 1992, p. 9). “…[T]he policy of regulatory forbearance contributed in a major way to the ultimate cost of the S&L crisis” (CBO 1992, p. 8). “…[I]t is the market value of an institution’s capital that the supervisory authorities should measure and monitor” (Brookings 1989, p. 12).

Delays in recognition made losses much larger because managers who knew their institution was insolvent or nearly insolvent had a strong incentive to ramp up risk in what was called ‘resurrection risk taking’. “Excessive risk taking and even fraud flourished in an environment of virtually nonexistent market discipline and totally inadequate government constraints” (Barth 1991, p. 4).

More fundamentally, however, the reason weak thrifts and banks were able to get away with ramping up risk and deepening losses was that deposit insurance protection insulated them from the discipline of the market that they otherwise would have faced: “Deposit insurance results in a process of Gresham’s law: Depositors have no incentive to look to what the S&L does with their money. Financial institutions which engage in riskier investments can offer higher returns, and only these promised returns matter to the depositors” (Stiglitz 1992, pp. 3-4).

It was widely agreed that “…the major culprit in the thrift crisis is federal deposit insurance…the scope of the crisis was magnified by the way the federal insurance system was structured” (Barth and Brumbaugh 1992b, p. 39). “Deposit insurance encourages risk-taking, especially by depository institutions whose capital has been completely or nearly depleted…” (Brookings 1989, p. 2). “The failure of depository institutions in the 1980s has raised serious concerns about the federal system of deposit insurance. Several factors have been identified as having contributed to the failure of numerous thrifts…and many commercial banks. A consensus is emerging that the most important underlying cause was the specific way in which the deposit insurance system…was structured and administered in the early 1980s” (CBO 1990, p. 1).

By 1991, the recognition of the problem with delayed recognition of loss by insured banks had led to some major regulatory change in the form of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation Improvement Act (FDICIA): “The belief that regulators had not acted promptly to head off problems was again evident in the FDICIA Act of 1991. This act was aimed largely at limiting regulatory discretion in monitoring and resolving industry problems. It prescribed a series of specific ‘prompt corrective actions’ to be taken as capital ratios of banks and thrifts declined to certain levels; mandated annual examinations and audits; prohibited the use of brokered deposits by undercapitalized institutions…” (FDIC 1997, pp. 10-11).

But that reform did not require that all securities, much less the whole banking franchise, be marked to market, as shown by the recent events at Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank – when runs by uninsured depositors followed knowledge about the magnitude of unrecognised losses. More broadly, many proposals by academics to bring more information from financial markets into the regulatory and supervisory process have gone unheeded. Dodd-Frank created a raft of new rules after 2010, but made no progress in bringing timely information from markets into regulation or supervision.

Why do regulators and politicians (who control the regulatory and supervisory process) consistently reject proposals that would speed the recognition of loss and produce timely intervention into weak financial institutions, despite the lessons from the 1980s (and from virtually every other banking crisis) of how beneficial such timely intervention would be? There is a cynical interpretation: Banks don’t like discipline and they have friends in high places who they are able to reward for protecting them from it. Furthermore, politicians and regulators not only gain from those rewards, they don’t like inconvenient, sudden market exigencies that create difficult challenges for them, which might crop up at a particularly awkward time (credit contractions are not helpful to their electoral prospects). It follows that “[s]uppressing information on the weakening condition of insured deposit institutions lessens market pressure on politicians and top regulators and creates rents for them to share” (Kane 1992, p. 164).

That hypothesis by Edward Kane was confirmed by detailed analysis of how politicians behaved during the 1980s banking crisis. “Our analytical perspective centers on the institutional structure of congressional decision making and on incentives faced by individual congressmen. These incentives led to intervention by some legislators on behalf of constituents (individuals and thrift institutions) to urge regulatory relief. Systemwide, they also resulted in delay in recognizing the magnitude of the problems facing FSLIC” (Romer and Weingast 1992, p. 169). “Massive gambling for resurrection was allowed to proceed because Congress intervened in the regulatory process to establish and enforce a policy of forbearance” (Romer and Weingast 1992, p. 171).

There are three old policy lessons this history illustrates. First, you should pay attention to market value, not book value, when judging the conditions of banks. The Fed started raising rates in 2022 and regulators knew the effects on banks’ true economic condition, but were slow to react because of the lack of use of market information in the regulatory and supervisory processes, including phony hold-till-maturity accounting for securities.

Second, prompt corrective action is crucial to limiting losses and avoiding systemic spillovers; if the supervisors had intervened to force Silicon Valley Bank (SBL) and Signature Bank (and another 200 banks currently vulnerable for similar reasons, according to Jiang et al. 2023) to maintain adequate capital, under-capitalised banks either would have raised the funds needed, or been resolved with no losses to uninsured depositors, and no fallout of related concerns at other banks. US supervisors need to move quickly to resolve the problems at the remaining 200 banks before those problems produce either resurrection risk taking (if their uninsured deposits become insured by the nervous regulators) or a new round of uninsured deposit runs (if they do not).

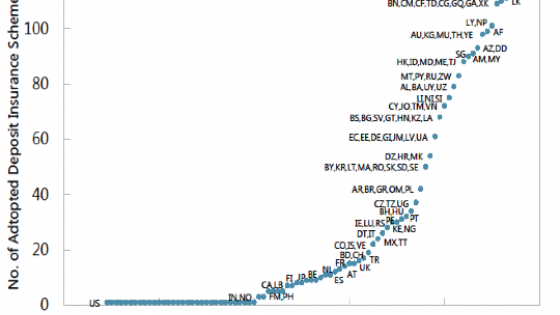

Third, it would be very unwise for regulators and politicians to learn from this crisis that all deposits should be insured. Clearly, a major positive difference from the 1980s is that Silicon Valley Bank and Signature relied largely on uninsured deposits. As their risk of failure grew, uninsured depositors (who were slow to respond) still responded fast enough to prevent the banks from becoming deeply insolvent. If those deposits had been insured ex ante, we may now be quietly experiencing resurrection risk taking from Silicon Valley Bank and Signature, with much larger losses in the future. Thus, despite the disruption, the current crisis illustrates the usefulness of the market discipline that comes from limiting deposit insurance protection. Add that example to the long (and unanimous) formal academic literature showing that increasing the generosity of deposit insurance increases systemic risk (for recent contributions, see Demirgüç-Kunt et al. 2008a, 2008b, Calomiris and Jaremski 2016a, 2016b, 2019, Calomiris and Chen 2022).

In case politicians and regulators are interested in real reform this time, here is a short list. First, get rid of hold-till-maturity book value accounting for securities and apply that same lesson to disallow the Fed from valuing collateral in its lending (as it just has) at artificially inflated values.

Second, embrace proposals for making prompt corrective action more meaningful by bringing information from other markets into the supervisory and regulatory process as indicators of bank failure risk. The SRISK measure of a bank’s fragility and the potential extent of its undercapitalisation in a downturn (advocated by Acharya et al. 2016) would be one obvious smart choice as a supervisory tool to guide such interventions. Even better, one could go deeper to incorporate market values into regulatory requirements, as in the CoCos proposal advocated by Flannery (2009) and by Calomiris and Herring (2013). Such a requirement makes it less likely that supervisory interventions will be needed because it creates strong incentives for banks to maintain large buffers of true equity capital and raise new equity capital in the wake of asset losses. Isn’t it high time to bring a little market information, and the discipline that it would create for regulatory and supervisory action, into government oversight of banking?

As the work of Kane (1992) and Romer and Weingast (1992) showed in olden days, and as Calomiris and Haber (2014) confirm in their analysis of bank regulatory history around the world, it will take more than sound economic reasoning to make these sorts of changes happen. The political equilibrium that enables inaction must first be turned upside down, which depends on a popular movement to empower the deep insights of history and financial theory. In a prior VoxEU column ten years ago (Calomiris 2013), I said that such meaningful reforms were unlikely, and that remains my view.

References

Acharya, V V, L H Pedersen, T Philippon and M Richardson (2016), “Measuring Systemic Risk”, Review of Financial Studies 30(1): 2-47.

Barth, J R (1991), The Great Savings and Loan Debacle, American Enterprise Institute.

Barth, J R and R D Brumbaugh Jr. (1992a), “Preface”, in The Reform of Federal Deposit Insurance: Disciplining the Government and Protecting Taxpayers, Harper Business.

Barth, J R and R D Brumbaugh Jr. (1992b), “The Industry Thrift Crisis: Revealed Weaknesses in the Federal Deposit Insurance System”, in J R Barth and R D Brumbaugh Jr. (eds.), The Reform of Federal Deposit Insurance: Disciplining the Government and Protecting Taxpayers, Harper Business, pp. 36-116.

Benston, G J, M Carhill and B Olasov (1992), “Market Value versus Historical Cost Accounting: Evidence from Southeastern Thrifts”, in J R Barth and R D Brumbaugh Jr. (eds.), The Reform of Federal Deposit Insurance: Disciplining the Government and Protecting Taxpayers, Harper Business, pp. 277-304.

Brookings Taskforce on Depository Institutions Reform (1989), Blueprint for Restructuring America’s Financial Institutions, Brookings Institution.

Calomiris, C W (2013), “Meaningful Banking Reform and Why It Is So Unlikely”, VoxEU.org, 8 January.

Calomiris, C W and S Chen (2022), “The Spread of Deposit Insurance and the Global Rise in Bank Asset Risk since the 1970s”, Journal of Financial Intermediation 49.

Calomiris, C W and S H Haber (2014), Fragile By Design: The Political Origins of Banking Crises and Scarce Credit, Princeton University Press.

Calomiris, C W and R J Herring (2013), “How to Design a Contingent Convertible Debt Requirement That Helps Solve Our Too-Big-to-Fail Problem”, Journal of Applied Corporate Finance 25.

Calomiris, C W and M Jaremski (2016a), “Deposit Insurance: Theories and Facts”, Annual Review of Financial Economics 8: 97-120.

Calomiris, C W and M Jaremski (2016b), “The expansion of liability insurance availability and its effectiveness in limiting systemic risk”, VoxEU.org, 1 June.

Calomiris, C W and M Jaremski (2019), “Stealing Deposits: Deposit Insurance, Risk Taking and the Removal of Market Discipline in Early 20th Century Banks”, Journal of Finance 74: 711-754.

Carron, A S (1982), The Plight of Thrift Institutions, Brookings Institution.

Congressional Budget Office (1990), Reforming Federal Deposit Insurance, September.

Congressional Budget Office (1992), The Economic Effects of the Savings & Loan Crisis, CBO, January.

Demirgüç-Kunt, A, E J Kane and L Laeven (2008a), Deposit Insurance Around the World: Issues of Design and Implementation, Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press.

Demirgüç-Kunt, A, E J Kane and L Laeven (2008b), “Determinants of deposit-insurance adoption and design”, Journal of Financial Intermediation 17: 407-438.

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (1997), History of the Eighties—Lessons for the Future, Volume I: An Examination of the Banking Crises of the 1980s and Early 1990s.

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (1998), The FDIC and RTC Experience: Managing the Crisis, August.

Flannery, M J (2009), “Stabilizing Large Financial Institutions with Contingent Capital Certificates”, Working Paper, Federal Reserve Bank of New York, 5 October.

Jiang, E X, T Piskorski and A Seru (2023), “Monetary Tightening and U.S. Bank Fragility in 2023: Mark-to-Market Losses and Uninsured Depositor Runs?”, SSRN Working Paper, 13 March.

Kane, E J (1992), “The Incentive-Incomptability of Government-Sponsored Deposit-Insurance Funds”, in J R Barth and R D Brumbaugh Jr. (eds.), The Reform of Federal Deposit Insurance: Disciplining the Government and Protecting Taxpayers, Harper Business, pp. 144-166.

Kaufman, G G (1992), “Lender of Last Resort, Too Large To Fail, and Deposit-Insurance Reform”, in J R Barth and R D Brumbaugh Jr. (eds.), The Reform of Federal Deposit Insurance: Disciplining the Government and Protecting Taxpayers, Harper Business, pp. 246-258.

Pratt, R T (1988), “Testimony Before the Committee on Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs, United States Senate”, 3 August.

Romer, T and B R Weingast (1992), “Political Foundations of the Thrift Debacle”, in J R Barth and R D Brumbaugh Jr. (eds.), The Reform of Federal Deposit Insurance: Disciplining the Government and Protecting Taxpayers, Harper Business, pp. 167-202.

Stiglitz, J E (1992), “The S&L Bailout”, in J R Barth and R D Brumbaugh Jr. (eds.), The Reform of Federal Deposit Insurance: Disciplining the Government and Protecting Taxpayers, Harper Business, pp. 1-12.

White, L J (1991), The S&L Debacle: Public Policy Lessons for Bank and Thrift Regulation, Oxford University Press.