The COVID-19 pandemic gave rise to unprecedented global economic conditions. To mitigate the health and economic fallout from the pandemic, governments around the world engaged in large fiscal support programmes (Müller et al. 2020). The programmes increased the demand for consumption goods, but production of these goods did not adjust quickly enough to meet the sharp increase in demand. This imbalance between supply and demand across countries contributed to the ongoing inflation outburst (see de Soyres et al. 2023).

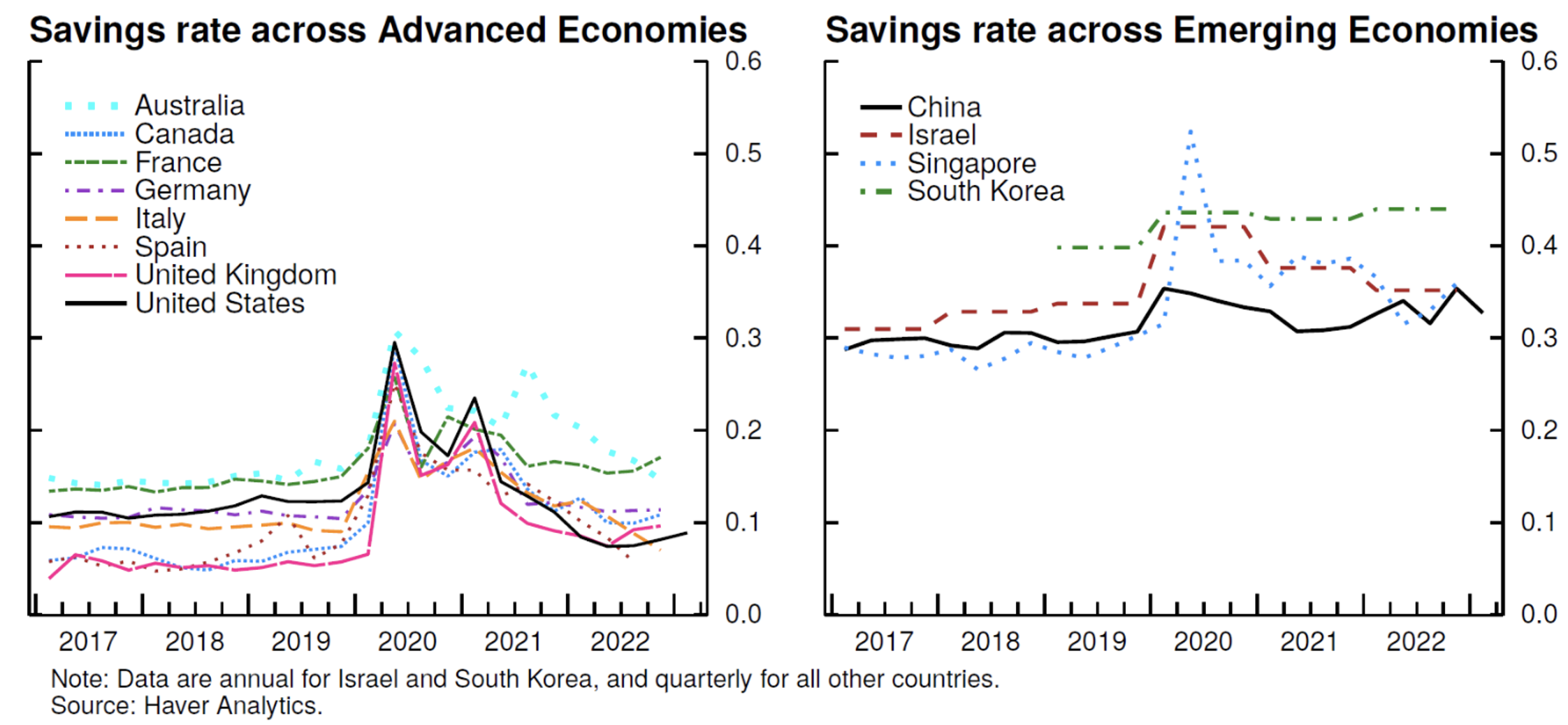

While aggregate demand increased sharply in response to fiscal transfers, households did not immediately spend out of these additional resources, as documented in Gorodnichenko et al. (2020). The combination of curtailed spending and resilient household income due to the fiscal support led to a large increase in personal savings rates in many countries around the world. As can be seen in Figure 1, the savings rate increased by a factor of two or more in advanced economies during the pandemic, while changes were more modest in emerging economies.

Figure 1 Evolution of savings rates during the COVID-19 pandemic

Though some have argued that excess savings are unlikely to stoke aggregate demand (see Eggertsson et al. 2021), there is agreement that part of the stock of savings accumulated during the pandemic reflects savings amassed due to a lack of spending opportunities, which could subsequently fuel spending. Since such savings cannot be separately observed, an important question going forward revolves around the usage of the overall stock of household savings, and the role that excess savings will play in fuelling spending in the quarters to come.

In this column, we put the current excess-savings episode into historical context by examining past recessionary periods. We observe that, while the current juncture is unprecedented, historical experience suggests that the extent to which further drawdowns of excess savings support aggregate demand is likely to be heterogeneous across countries but waning in importance overall.

Quantifying excess savings during the COVID-19 pandemic

We define excess savings as the amount of savings arising from above-trend savings rates.

For each country, we collect its aggregate savings rate over time and employ the Hamilton (2018) filter to extract a time-varying trend savings rate from which we compute flows and stocks of excess savings.

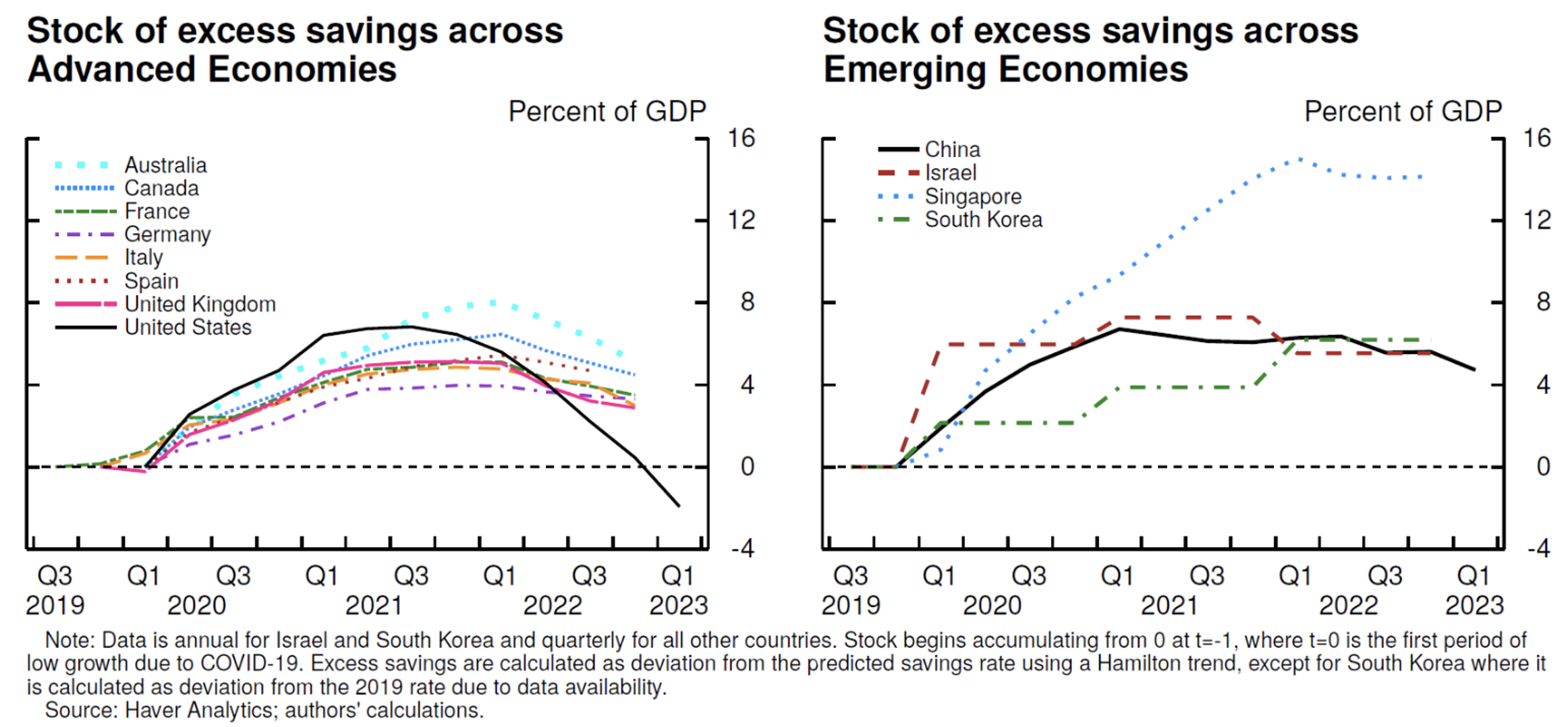

In Figure 2, we present our estimates for the accumulated stock of excess savings. Broadly speaking, advanced economies have followed similar hump-shaped paths so far, with a large increase in excess savings in 2020–2021 followed by a decrease in the stock of excess savings, which reflects a period of below-trend savings rates as households use their accumulated buffer to fuel consumption. That said, we note that the path in the US differs slightly from other countries, as its stock of excess savings increased more rapidly, peaking in 2021Q3, and then decreased more quickly. As a result, its excess savings stock, computed according to our method, is currently completely depleted, which contrasts with other advanced economies where households still hold excess savings of about 3% to 5% of GDP. Given the more rapid drawdown of excess savings, aggregate demand in the US is likely to have been supported more than in other countries over the past year.

Figure 2 Evolution of the accumulated stock of excess savings during the pandemic

Notes: Data is annual for Israel and South Korea and quarterly for all other countries. Stock begins accumulating from 0 at t=−1, where t=0 is the first period of low growth due to COVID-19. Excess savings are calculated as deviation from the predicted savings rate using a Hamilton trend, except for South Korea where it is calculated as deviation from the 2019 rate due to data availability. Source: Haver Analytics; authors’ calculations.

The evolution of the excess savings stock is more heterogeneous in emerging economies. Most countries saw a significant accumulation in the past three years, but the size of the increase differs from country to country. Additionally, whereas advanced economies all follow a hump-shaped path, the trajectories are more varied for emerging economies. However, as these countries feature more volatile savings rates even before the pandemic, the estimates of excess savings should be considered with greater caution because deviations from the trend savings rate are more frequent, even outside of recessionary episodes.

Historical perspective on recessions and excess savings

To extract further insights into the evolution of excess savings, we look to history as a guide and examine 34 episodes spanning nine advanced economies and 29 episodes spanning six emerging economies.

For each advanced economy, we define a recession as two or more consecutive quarters of negative growth.

We then inspect each of these episodes and define an ‘excess savings’ recession as a recession during which the aggregate savings rate rises by more than the cross-country unconditional median savings rate.

Since GDP growth is typically higher, on average, and more volatile in emerging economies, we adapted our definition of a recession for emerging economies as one or more quarters of negative growth.

For each country and recession, we define an excess savings episode as a recession during which the aggregate savings rate rises by more than the country-specific unconditional median savings rate.

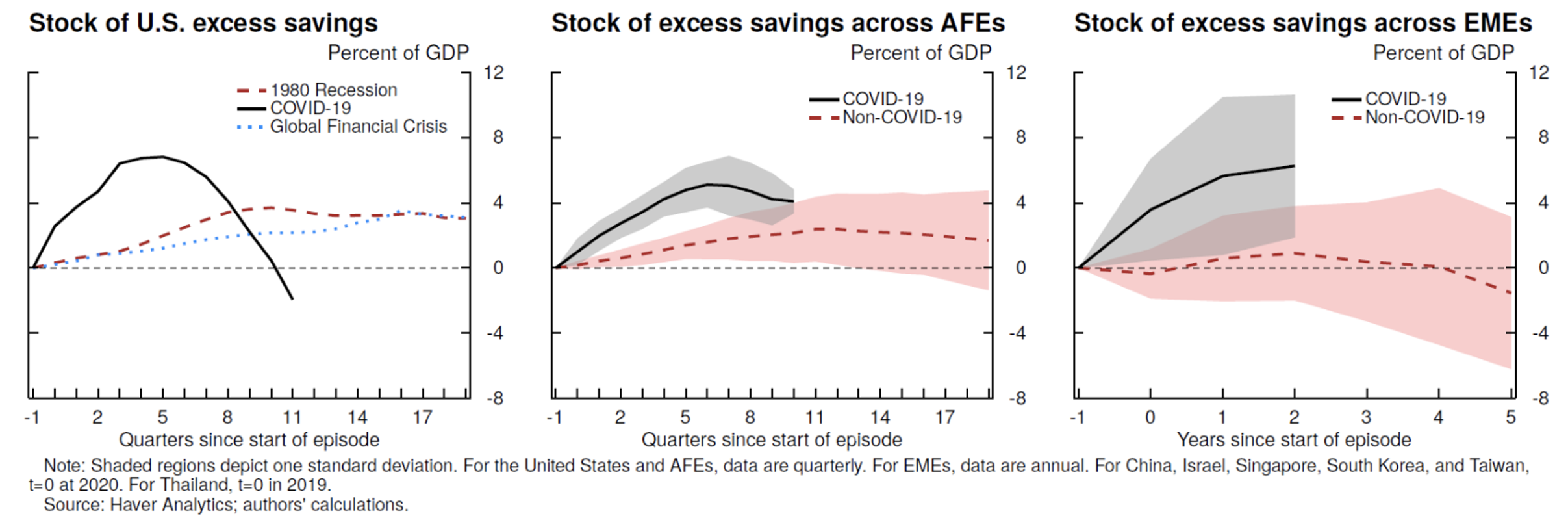

Figure 3 presents our results for the US, other advanced economies, and emerging market economies. In the US, we uncover two prior recessions, besides COVID-19, during which households accumulated excess savings. The COVID-19 recession was unique in that it featured a remarkable rise in the stock of excess savings based on the methodology we use, peaking at nearly 7% of GDP, followed by an equally swift fall. Our results indicate that the stock of excess savings in the US was depleted in 2023Q1, three years after the onset of COVID-19. On the other hand, the early-1980s recession and the Global Financial Crisis are characterised by a more gradual build-up and subsequent rundown in excess savings.

Figure 3 Historical comparison of excess savings evolutions

Notes: Shaded regions depict one standard deviation. For the US and advanced foreign economies (AFEs), data are quarterly. For emerging market economies (EMEs), data are annual. For China, Israel, Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan, t=0 at 2020. For Thailand, t=0 in 2019. Source: Haver Analytics; authors’ calculations.

Across the advanced foreign economies, stocks of excess savings during COVID-19 evolved as in the US, with an average peak reaching nearly 6% of GDP. Notably, however, the stocks of excess savings evolved more gradually than in the US, with the average reaching its peak nearly two years after the onset of COVID-19 and standing at close to 4% by 2022Q3.

Relative to COVID-19, the non-COVID-19 episodes feature a more gradual evolution in the stock of excess savings for the advanced foreign economies, as it does in the US. The average stock of excess savings during non-COVID-19 episodes in advanced foreign economies reaches its peak about three years after the start of the recession. Based on the shaded areas, however, there is a meaningful amount of heterogeneity across countries.

The stock of excess savings accumulated across emerging market economies during COVID-19 is similar in size to those of the advanced foreign economies, with an average of around 6% of GDP. The accumulation of these stocks appears to have decelerated in the emerging market economies, suggesting that they too might have peaked about two years after the onset of COVID-19. Relative to the advanced foreign economies, however, there is greater dispersion in COVID-19-related excess savings across the emerging market economies. The stock of excess savings during non-COVID-19 episodes hovers around 0% of GDP for the emerging market economies.

Implications for inflation in advanced foreign economies

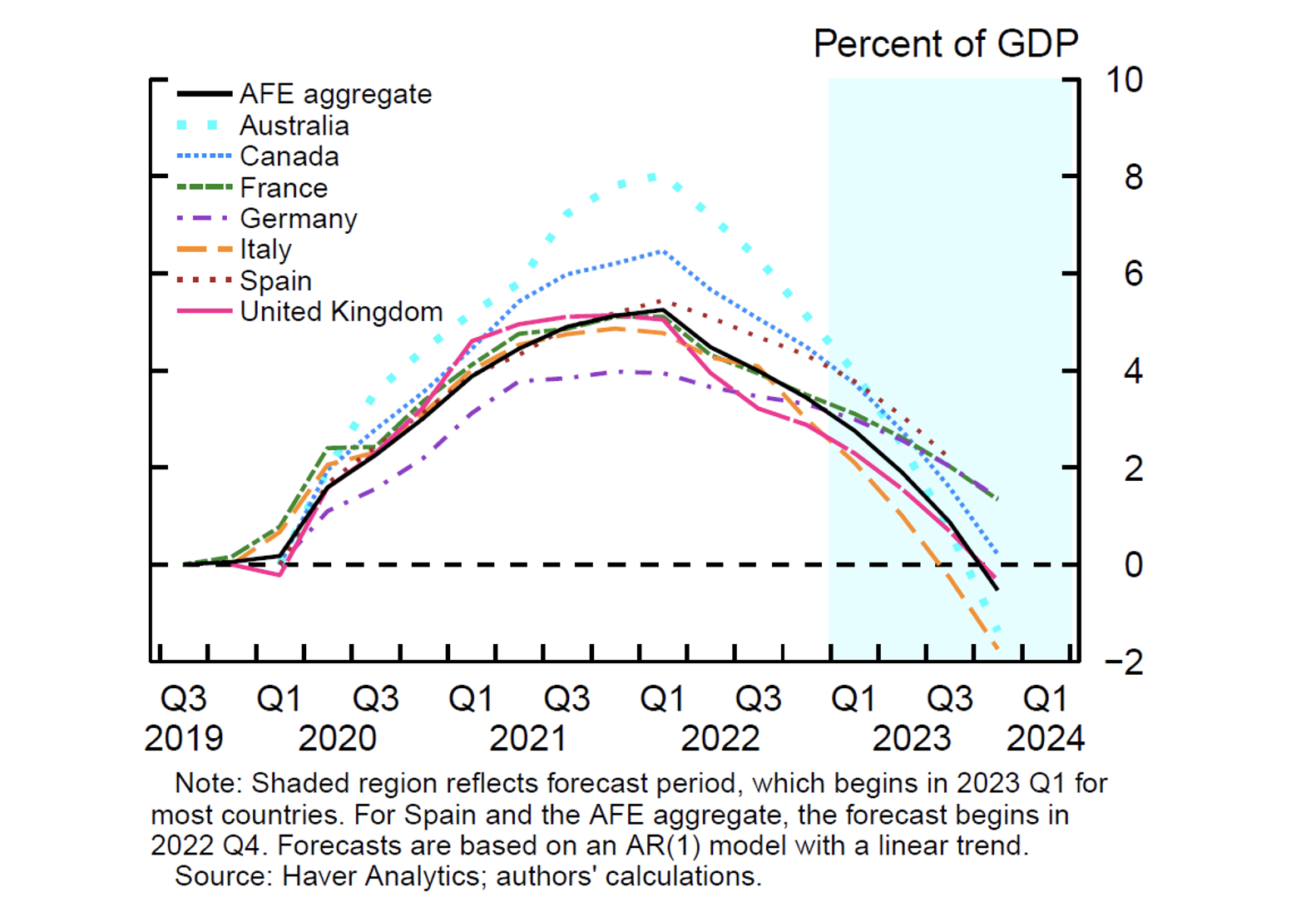

While the above analysis suggests that excess savings in the US have been depleted, the advanced foreign economies continue to hold a significant stock of excess savings. To understand the extent to which the unwinding of excess savings may continue to support demand and inflation in the advanced foreign economies, we estimate simple univariate time series models to project the stocks of excess savings over the next few quarters. For each advanced foreign economy, we regress the flow of excess savings on its lag and time trend, forecast these flows over four quarters, and construct an implied stock of savings, which gives us an estimate of when we might expect the stock of excess savings to be depleted.

Figure 4, which plots these projections, suggests that the average stock of excess savings in the advanced foreign economies will continue to support aggregate demand until 2023Q4, at which time it will be depleted. Though the estimated time series models fit the data fairly well, this straightforward exercise assumes no new fiscal policies geared toward supporting real incomes and no change in household savings behaviour.

Figure 4 Forecasted stock of excess savings in advanced foreign economies

Notes: Shaded region reflects forecast period, which begins in 2023Q1 for most countries. For Spain and advanced foreign economies aggregate, the forecast begins in 2022Q4. Forecasts are based on an AR(1) model with a linear trend. Source: Haver Analytics; authors’ calculations.

The recent outburst of inflation reflects imbalances between demand and supply that were partly enhanced by government fiscal support (see, for example, de Soyres et al. 2023). As advanced foreign economies are expected to continue to use their accumulated stock of excess savings to fuel consumption in the quarters to come, the resulting strength in aggregate demand could continue to be a source of price pressures.

Final remarks

Household savings rates spiked across several countries following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. In this note, we construct a measure of excess savings for the US, advanced foreign economies, and emerging market economies, and compare the COVID-19 recession to past recessionary episodes. While accumulated excess savings during COVID-19 were unprecedented in size, they have been unwound in the US, declined in the advanced foreign economies, and slowed in the emerging market economies.

Relative to COVID-19, past episodes are characterised by smaller increases in excess savings and greater persistence in the stock of excess savings. Absent any further shocks to disposable income or savings behaviour, our analysis suggests that the accumulated average excess savings in advanced foreign economies should be unwound by the end of the year.

Authors' note: The views expressed in this column are our own, and do not represent the views of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve, nor any other person associated with the Federal Reserve System.

References

Abdelrahman, H, and L E Oliveira (2023), “The rise and fall of pandemic excess savings”, FRBSF Economic Letter 2023–11, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

Aladangady, A, D Cho, L Feiveson, and E Pinto (2022), “Excess savings during the COVID-19 pandemic”, FEDS Notes, Washington, DC: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 21 October.

Müller, G, B Born, R Luetticke, and C Bayer (2020), “The coronavirus stimulus package: Quantifying the transfer multiplier”, VoxEU.org, 24 April.

Cascaldi-Garcia, D, M Orak, and Z Saijid (2023), “Drivers of post-pandemic inflation in selected advanced economies and implications for the outlook”, FEDS Notes, Washington, DC: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 13 January.

Gorodnichenko, Y, M Weber, and O Coibion (2020), “How US consumers use their stimulus payments”, VoxEU.org, 8 September.

de Soyres, F, A M Santacreu and H L Young (2023), “Demand-supply imbalance during the COVID-19 pandemic: The role of fiscal policy”, Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review 105(1): 21–50.

Eggertsson, G, G Primiceri, and F Bilbiie (2021), “US ‘excess savings’ are not excessive”, VoxEU.org, 1 March.

Hamilton, J D (2018), “Why you should never use the Hodrick-Prescott filter”, The Review of Economics and Statistics 100(5): 831–43.