The Brazilian economy is facing considerable competitiveness challenges (Bonelli and Pinheiro 2012). After several years of strong expansion, the recent slowdown seems related to supply-side difficulties stemming from a wide range of inefficiencies and rising costs, rather than insufficient aggregate demand. Such inefficiencies and costs have increasingly burdened economic activity and have shown signs of worsening in recent years.

Our recent research uses a toolkit developed by Reis and Farole (2012) that examines Brazilian export performance over the last 15 years (Canuto, Cavallari and Reis 2013). The objective was to generate hypotheses to identify factors that have been inhibiting exports and industrial expansion.

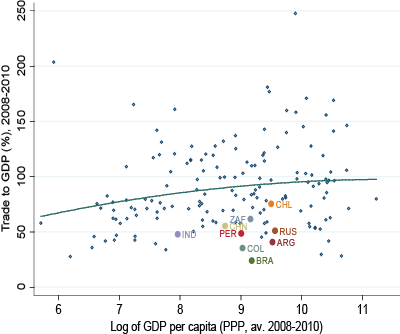

Figure 1. Trade to GDP (%)

Source: World Bank World Development Indicators.

Export performance, 1998–2011

The recent aggregate performance of Brazilian exports can be considered as reasonably favourable. In the wake of strong global economic growth, expansion of international trade and favourable commodity prices, Brazilian exports of goods and services grew 262% between 2000 and 2010, almost twice the global average and around half of the other BRICS countries – that is, Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa.

Trade openness in Brazil, even considering the level of per-capita income, is among the lowest in the world – 22.8% of GDP in 2010. Larger economies do tend to be more dependent on their domestic markets. However, compared to other BRICS, the level of trade integration remains below the expected line, with no recent signs of improvement (Figure 1).

Diversification of exports

The global economic crisis highlighted the importance of diversification in reducing risks associated with growth volatility. Although predicted by trade theory, the degree of vertical specialisation, which emerged from increasing fragmentation of trade in global supply chains, has surprised many with its intensity. Consequently, economic diversification is now a high priority on the policy agenda for most developing countries.

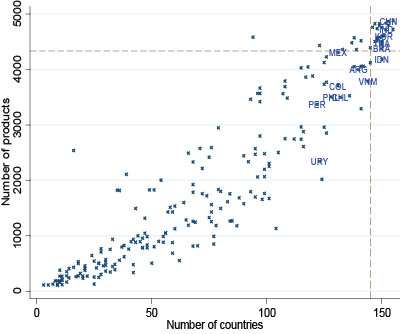

Brazil is a global trader, endowed with a wide range of natural resources along with a well-diversified industrial structure. This translates into an impressive level of export diversification in destinations and products. When compared with other countries (Figure 2), the Brazilian economy has been able to sell a large number of products in many markets. Herfindahl Index calculations for a large group of countries show a high degree of market diversification of Brazilian exports (Canuto et al 2013).

Figure 2. Product and markets (2008–10)

Source: World Integrated Trade Solution.

Sophistication and technological content of exports

Using Lall classification to assess the technological content of the Brazilian exports, there is a clear reduction in the share of high-technology products between 2000 and 2010 – from 10.4 to 5%. Moreover, primary and resources-based products gained significant importance between 2000 and 2010. The share of the latter increased from 45.7% in 2000 to 62.9% ten years later.

The decrease in the share of high-technology product exports could have been the result of the excellent performance of commodity products in Brazil. However, this does not seem to be the case: when focusing only on the performance of high-technology international sales, there is only very modest growth. Between 2000 and 2010, Brazilian high-technology product exports expanded by 36%, a much lower growth rate than the one of the groups linked to natural capital. If this performance is compared with other BRICS, Brazil is among the weakest, along with Russia. In the same ten years, China and India increased exports of those products by 873 and 389%, respectively.

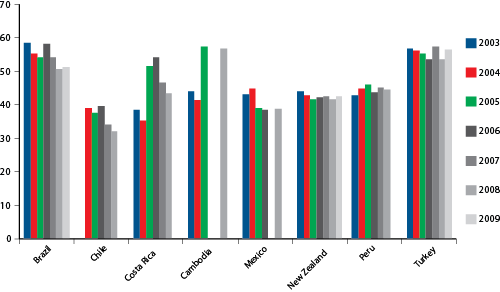

Firm-level dynamics of exports

The recent public availability of World Bank microdata allows an evaluation of the entry, exit, and survival dynamics of firms in global markets. The survival rate of exporters in Brazil stood at very high levels during 2003-09 (Figure 3), lower only than levels observed in Turkey. While this result can be considered positive, it reflects a small and decreasing entry rate of firms into foreign trade. The entry rate of exporters was already low in Brazil, and dropped further to 22%, much lower than the values observed in countries chosen for comparison (around 35%).

Lack of integration into global value chains may explain the low levels of dynamism in the export sector. The emergence of global production networks has changed the world trade landscape, and this has been a driving force behind emergent trade powerhouses, many of them located in Asia.

Figure 3. Exporter survival rate (one year, 2003–9)

Source: Export Dynamics Database.

Composition effects on exports

To argue that a country is more competitive in foreign trade than other countries just because of their better export performance is obviously too simplistic. First, export growth can be associated with the existence of composition effects and also performance effects. Two countries may have equally competitive exporters, but export performances can be different due to different composition of exports in terms of geographical and sector composition.

Using methodology described in Gaulier, Taglioni and Zignago (2012), Canuto, Cavallari, and Reis (2013) decomposed export growth and compared the results from Brazil with the other BRICS, the MIST group – that is, Mexico, Indonesia, the South Korea, and Turkey – and with the US, the EU, and Japan for the period 2005-11, as well as for the post-crisis sub-period, 2009-11.

The composition effect is important to explain Brazilian export performance between 2005 and 2011. The sum of geographical and sector effects in Brazil (3.3% per year) is the second highest, lower only than the impact observed in Russia. Additionally, the geographical composition effect predominated in the Brazilian case, which related to the fast growth of the Chinese economy.

Excluding the composition effects, the Brazilian export growth associated more directly to competitiveness is reduced to 1.8% per year – still significant, but less than China, India, Mexico, and Turkey – and after financial crisis it dropped to 1.1%, the lowest among developing countries.

These results suggest, despite the recent aggregate good performance, Brazilian exports were mostly benefiting from geographical and sector composition effects. Excluding the favourable environment, the ‘pure’ export performance is still positive, but of much lower intensity, and smaller than some of its major emerging economies.

Elements potentially associated with low competitiveness

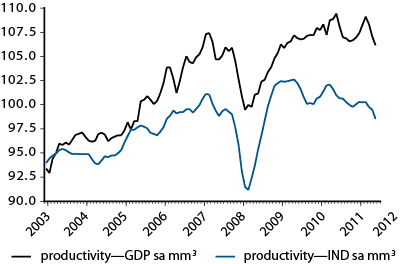

Low productivity gains in recent years have become a central issue for the low trade competitiveness of the Brazilian economy. Contrary to the pattern observed in the past, labour productivity in the industrial sector lagged behind overall economic productivity in recent years (Figure 4). Additionally, overall labour productivity recently showed signs of stabilisation, generating serious concerns. Improvements in the efficiency of services sectors have become vital to improving the productivity of all other economic sectors.

Figure 4. Industry and GDP: Evolution of labour productivity

Source: National Industry Confederation; Central Bank of Brazil.

Terms of trade and employment level

Wealth effects resulting from favourable terms of trade are among the main driving factors of Brazil’s recent economic growth. The gain in terms of trade has been approximately 40% since 2004 and helps explain the strong domestic consumption, along with the demographic bonus and the emergence of a new middle class stimulated by social inclusion policies.

The terms-of-trade impacts differ between tradeable and non-tradeable sectors. Foreign competition restricts the ability of local industry to pass through increasing costs, even in an environment of strong internal demand. Conversely, because service sectors can set prices much more easily, its power to dispute production factors internally is higher. This issue is especially important as the economy approaches full employment.

Figure 5. Real average wages

Source: Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia and Estatística.

One way to examine these effects is through the lens of different wage gains by consumers and producers. Accordingly, we deflated nominal wages not only by the index of consumer prices (IPCA), but also by the GDP deflator for the specific sector (Figure 5). Gains realised by consumers can be gauged by deflating wages by the IPCA. Clearly, the latter benefited from higher terms of trade. On the other hand, some producers – especially of non-tradeables – could take partial advantage of better prices and pay higher wages, absorbing some of the cost pressures. Demand for labour can still be argued as greater than in the absence of this external shock, and the economy moved toward full employment. Therefore, cost pressures revealed to be much more intense in non-commodity-related industrial sectors.

Unit labour costs

Increases in average real wages, concurrent to stagnant or falling labour productivity, have negatively affected Brazil’s export competitiveness. As presented earlier, both trends have been observed in Brazil after its fast recovery from the recent global crisis.

However, this effect was not observed before 2010, excluding the recessionary period, and can be characterised as an additional negative shock to export performance in recent years (Figure 6). As noted earlier, higher real wages from an industrial perspective were milder than those shown in Figure 6, given improving terms of trade. Nonetheless, although better terms of trade mitigated the impact of higher unit labour costs, analysis shows that it alleviated this uptrend only by about one fourth after 2010.

Figure 6. Unit labour cost in industry sector

Source: National Industry Confederation.

Exchange rates

Many economists have highlighted exchange-rate appreciation as a major factor explaining the recently disappointing export and industrial performances in Brazil. The general trend of appreciation is evident, considering the levels achieved earlier in the decade. Actually, given the significant gain in terms of trade, strengthening of the real exchange rate should be expected.

In fact, the real effective exchange rate index appreciation is certainly not negligible. Taking the average of the 2000/2001 biennium as the base, the average level throughout 2010 reached 70. Similarly, the dollar-denominated unit labour cost level reached 202 in 2010. Thus, although exchange-rate appreciation seems to be one of the elements of the low competitiveness of Brazilian exports, sluggish industrial-sector productivity performance and higher real wages seem to be more responsible for the current situation.

Business environment

The business environment has not helped Brazil face stronger competition in global markets. Among the 183 countries assessed in the World Bank Doing Business, Brazil is in the bottom half in the overall ranking. Among the ten categories analysed by this survey, Brazil fares relatively better in only two categories: obtaining electricity (51st) and protecting investors (79th). Among BRICS, the major highlight is South Africa, which features in the top half in eight out of ten categories, including first in obtaining credit and tenth in protecting investors.

Conclusions

Brazilian exports of goods and services have grown sharply in recent years, with sales nearly three times higher in 2010 than in 2000. Although a stronger currency is one of the factors behind the lower competitiveness of Brazil’s manufacturing exports, sluggish productivity performance, lack of dynamism at the firm level, business environment and a real-wage uptrend seem to explain a significant part of the overall loss of competitiveness.

The fact that trade openness in Brazil is among the lowest in the world deserves more attention. Pursuing greater global integration of the Brazilian economy can provide significant benefits in the medium and long terms.

This diagnostic reinforces the importance of resuming the agenda of microeconomic reforms, increasing the investment-to-GDP ratio, and advancing toward a better-skilled human-capital base. Promoting and rewarding productivity gains in a competitive economy, including the service sector, are the only options to accelerate growth and overcome possible middle-income growth traps.

References

Bonelli, R and Pinheiro, A C (2012), “Competitividade e Desempenho Industrial: Mais Que só Câmbio”, XXIV Fórum Nacional Rumo ao Brasil Desenvolvido.

Canuto, O, M Cavallari, and J Reis (2013), "Brazilian Exports: Climbing Down a Competitiveness Cliff", World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 6302, Washington, DC.

Gaulier, G, D Taglioni, and S Zignago (2012), “Export Performance in the Wake of the Global Crisis: Evidence from a New Database”, mimeo.

Reis, J, and Farole, T (2012), “Trade Competitiveness Diagnostic Toolkit”, World Bank, Washington, DC.