Over the last few decades, nationalistic political parties have gained support in Europe, while terrorist attacks have also been on the rise. Using biannual data from the European Social Survey, Peri et al. (2023) find an increase in satisfaction with the national government in the aftermath of terror attacks in the country of the respondent. A vast literature studies the relationship between terrorism and voters’ behaviour in the country of an attack, generally finding an increase in citizens’ support for right-wing parties (e.g. Berrebi and Klor 2008, Gould and Klor 2010, Hersh 2013, Giavazzi et al. 2023) and a negative impact on preferences for the incumbent party (e.g. Montalvo 2011), though there is also evidence of a ‘rally around the flag’ effect increasing the incumbent party’s popularity (e.g. Peri et al. 2023). Moreover, some authors find evidence of a long-lasting increase in overall political engagement in the aftermath of a terror attack (e.g. Hersh 2013, Balcells and Torrats-Espinosa 2018). My research adds to this literature by examining the effects of the 11 September 2001 attacks in the US (hereafter referred to as ‘9/11’) on the intentions of British voters, allowing for a trans-Atlantic assessment of the impact of terrorism on political preferences.

Terrorism impacts the behavioural outcomes of individuals far beyond the immediate victims due to fear of future attacks (e.g. Clark et al. 2020, Mirza et al. 2022) further propagated via the media (e.g. Becker and Rubinstein 2004, Giavazzi et al. 2023). Metcalfe et al. (2011) find that the 9/11 attacks in New York had a significant negative effect on the mental wellbeing of the British, in line with the large post-traumatic stress disorder impact in the US (e.g. Galea et al. 2002), possibly due to the fact that some 9/11 victims were British citizens.

Although the behavioural effects of terrorism on individuals only indirectly affected by the attacks are usually short-lived (e.g. Metcalfe et al. 2011, Clark at al. 2020), they may still cause sizable and long-lasting consequences if, for example, political elections were taking place close to the day of the attack (e.g. Montalvo 2011, Balcells et al. 2018). Moreover, the literature documents considerable heterogeneity of behavioural responses to terrorism, with those most vulnerable to stress – women, for example – affected the most (e.g. Mirza et al. 2022).

Data used for the empirical analysis are drawn from the British Household Panel (BHPS), a representative population survey of the UK, collected from 1992 to 2002,

with most interviews carried out in September and October of each year. The BHPS survey was addressed to over 18,000 respondents in 2001, with more than 5,000 individuals interviewed in September 2001, making it possible to precisely estimate the immediate impact of 9/11 on voting intentions.

Questions on “the party you would vote for tomorrow”,

if any, were asked in all the survey waves except the first one (wave 1992), which is therefore not included in the analysis. Questions on the party voted for at the last general election were also asked, enabling examination of whether individuals switched parties due to terrorism.

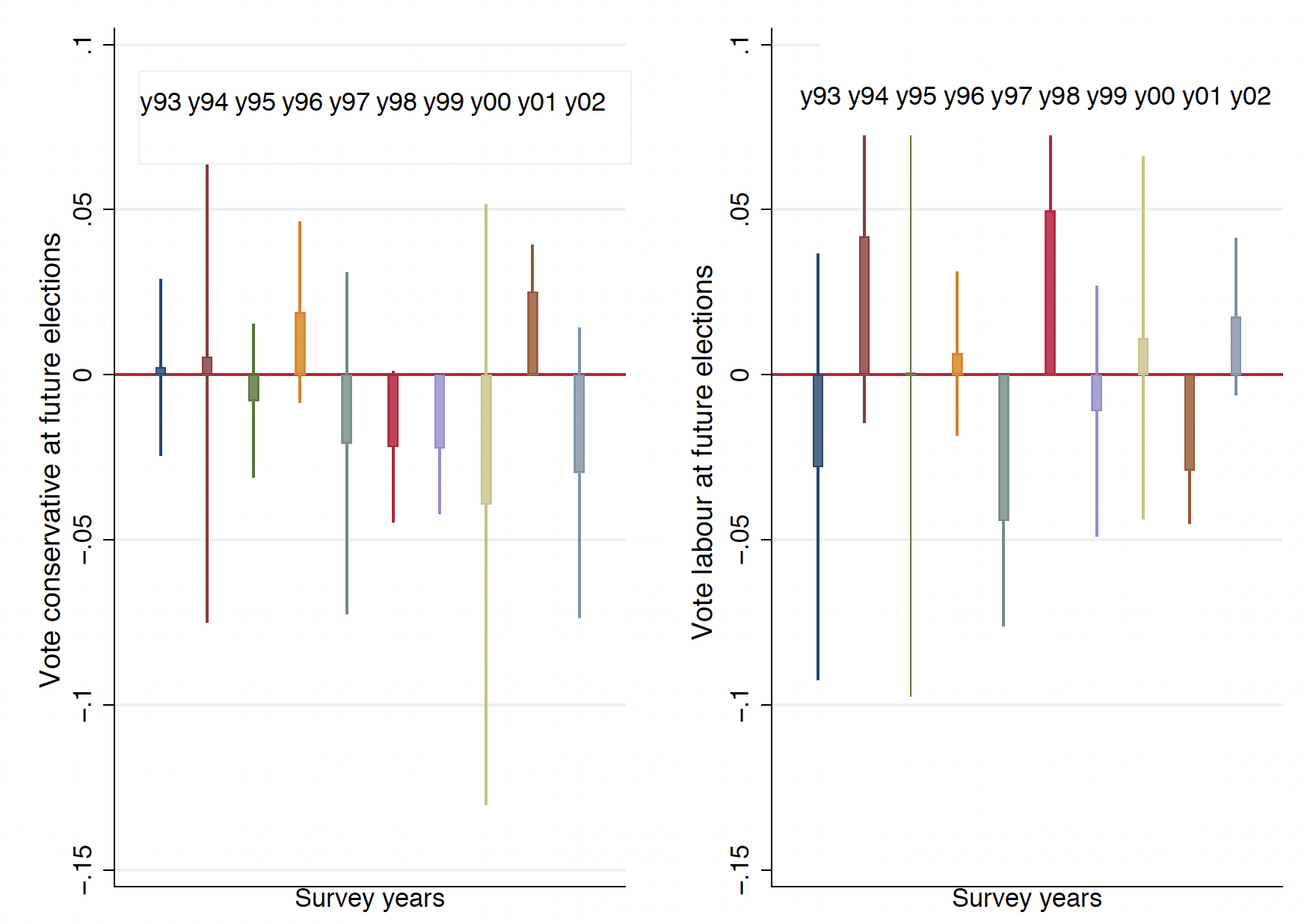

Using daily data drawn from the BHPS and a regression discontinuity design, as well as an event study approach (see Figure 1), reveals that 9/11 immediately increased the intention to vote for the Conservative Party in future elections by about 31%, and reduced prospective votes for the Labour Party by about 17%.

Figure 1 Visual results of estimation of RDD models year by year

Notes: The bar plots visualized confidence intervals around the estimates and centres the plot around zero, meaning that any estimate that crosses zero is statistically non-significant at the 5% level. The 11 September 1997 results, when a pre-legislative referendum was held in Scotland for the creation of a Scottish Parliament, had a negative impact on voting intentions for the incumbent national Labour party and no significant effect on voting intentions for the Conservative Party. Instead, the 11 September 1998 results marked a significant decline in intentions to vote Conservative and an increase in intentions to vote Labour, likely because a document revealing the incriminating results of a four-year-long investigation into US President Bill Clinton were made public that day. Also, on 11 September 1999, there is a significant decline in intentions to vote Conservative, perhaps due to the UN holding a meeting to restore peace in East Timor on that day, and the Indonesian President B. J. Habibie announcing that Indonesian soldiers would leave East Timor on 12 September 1999 (with Western Indonesia being seven hours ahead of GMT). No other 11 September day significantly affected voting intentions for the Conservative or the Labour Party, except for 11 September 2001, when terror struck New York.

These effects are driven by the preferences of men, as far as the increase in voting intentions for the right goes, and by the preferences of women in regard to the decline in prospective future Labour votes. This gendered pattern is perhaps due to cultural gender norms, with men wanting to secure more military interventions and military spending in the aftermath of terrorist attacks, and women feeling more doubtful about the adequacy of the incumbent to face future terror risks. Moreover, the estimates are significant for individuals out of work, who may spend more time in front of the media, but not for the employed, corroborating the hypothesis that the media channels the effects of terrorism and in line with the literature documenting a large media impact on electoral outcomes. The effects of interest are not significant for the college/university educated, who may be less sensitive to media exposure, but are statistically significant for respondents with a primary or mid-level education.

Furthermore, respondents who voted Labour at the last general election, which took place only a few months before 9/11, do not show any increase in prospective votes for the Conservative Party in the aftermath of 9/11, but only a decline in prospective votes for Labour. The opposite holds true for respondents who voted Conservative at the last general election, who report increased intentions to vote for the Conservative Party in a future election, due to 9/11, but register no decline in the probability of voting Labour. Individuals who reported having abstained from voting at the last election also report increased intentions to vote Conservative in the aftermath of 9/11 but no decline in prospective Labour votes. Intentions to vote for other political parties, such as the Liberal Democrats, the Greens, the Scottish National Party, or the Welsh nationalist party were not significantly affected by 9/11. Therefore, the findings in this study confirm earlier work that terror increases political preferences for right-wing parties and weakens political support for the incumbent party.

Finally, the effects of 9/11 on British voting intentions were short-lived – vanishing a year after 9/11 (see Figure 1) – and did not impact later general election outcomes, as the Labour Party was re-elected in 2005. Nonetheless, as the size of the immediate effects is large (see Figure 1), terror that was timed closer to the elections might have substantially affected the outcomes. This deserves the attention of policymakers. Specific programmes to reassure citizens in the aftermath of terror could be designed, such as awareness campaigns to reduce terrorism-related stress and fear targeted at the most vulnerable groups in society.

References

Balcells, L and G Torrats-Espinosa (2018), “Using a natural experiment to estimate the electoral consequences of terrorist attacks”, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115(42): 10624–10629.

Berrebi, C and E F Klor (2008), “Are Voters Sensitive to Terrorism? Direct Evidence from the Israeli Electorate”, American Political Sciences Review 102(3): 279–301.

Clark, A, O Doyle and E Stancanelli (2020), “The Impact of Terrorism on Individual Well-being: Evidence from the Boston Marathon Bombing”, The Economic Journal 130(631): 2065–2104.

Galea, S, H Resnick, J Ahern, J Gold, M Bucuvalas, D Kilpatrick, J Stuber and D Vlahov (2002), “Post-traumatic stress disorder in Manhattan, New-York City after the September 11th terrorist attacks”, Journal of Urban Health 79(3): 340–53.

Giavazzi, F, F Ighault, G Lemoli and G Rubera (2023), “Terrorist Attacks, Cultural Incidents, and the Vote for Radical Parties: Analyzing Text from Twitter”, American Journal of Political Science, forthcoming.

Gould E D and E F Klor (2010), “Does Terrorism Work?”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 125(4): 1459–1510.

Hersh, E D (2013), “Long-term effect of September 11 on the political behaviour of victims’ families and neighbors”, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 110(52): 20959–20963.

Metcalfe, R, N Powdthavee and P Dolan (2011), “Destruction and distress: Using a quasi-experiment to show the effects of the September 11 attacks on mental well-being in the United Kingdom”, Economic Journal 121(550): 81–103.

Mirza, D, E Stancanelli and T Verdier (2022), “Household Expenditure in the Wake of Terrorism: evidence from high frequency in-home-scanner data”, Economics and Human Biology 46, August.

Montalvo, J G (2011), “Voting after the bombings: A natural experiment on the effects of terrorist attacks on democratic elections”, Review of Economics and Statistics 93(4): 1146–1154.

Peri, G, D I Rees and B Smith (2023), “Terrorism and Political Attitudes”, Regional Science and Urban Economics 99 (forthcoming).

Schüller, S (2015), “The 9/11 Conservative Shift”, Economic Letters 135: 80–84.

Stancanelli, E (2023), “British voting intentions and the far reach of 11 September terrorist attacks in New York”, IZA Discussion Papers, forthcoming.