While ‘fool’s gold’ (iron pyrites) can be found by mining, most mining is a productive activity. Similarly, when properly conducted, so-called ‘data mining’ is no exception –despite many claims to the contrary. Early criticisms, such as the review of Tinbergen (1940) by Friedman (1940) for selecting his equations “because they yield high coefficients of correlation”, and by Lovell (1983) and Denton (1985) of data mining based on choosing ‘best fitting’ regressions, were clearly correct. It is also possible to undertake what Gilbert (1986) called ‘strong data mining’, whereby an investigator tries hundreds of empirical estimations, and reports the one she or he ‘prefers’ – even when such results are contradicted by others that were found. As Leamer (1983) expressed the matter: “The econometric art as it is practiced at the computer terminal involves fitting many, perhaps thousands, of statistical models. One or several that the researcher finds pleasing are selected for reporting purposes”. That an activity can be done badly does not entail that all approaches are bad, as stressed by Hoover and Perez (1999), Campos and Ericsson (1999), and Spanos (2000) – driving with your eyes closed is a bad idea, but most car journeys are safe.

Why is ‘data mining’ needed?

Econometric models need to handle many complexities if they are to have any hope of approximating the real world. There are many potentially relevant variables, dynamics, outliers, shifts, and non-linearities that characterise the data generating process. All of these must be modelled jointly to build a coherent empirical economic model, necessitating some form of data mining – see the approach described in Castle et al. (2011) and extensively analysed in Hendry and Doornik (2014).

Any omitted substantive feature will result in erroneous conclusions, as other aspects of the model attempt to proxy the missing information. At first sight, allowing for all these aspects jointly seems intractable, especially with more candidate variables (denoted N) than observations (T denotes the sample size). But help is at hand with the power of a computer.

How can more variables than observations be handled?

One simple answer is to take all N candidate variables, denoted zt; calculate the correlations of each with the chosen dependent variable yt; then regress yt on that variable and test its significance. Keep adding the next highest correlated variable zj,t till either an insignificant outcome is found, or a maximal desired model size is reached. This shows the feasibility of selecting an equation when N > T. However, such an algorithm rarely works well in economics, whether augmented by also eliminating variables that have become insignificant at the desired level when others are added (stepwise regression, widely known as unwise regression), or by constraints on the magnitudes of estimated coefficients (Lasso), as discussed below.

The discovery that it was possible to allow for more variables than observations outside of the context of 1-step forward search algorithms (like stepwise and Lasso) came about by accident. The Magnus and Morgan (1999) experiment tasked apprentices to try to replicate the analysis of a dataset that might have been carried out by three different experts (Leamer, Sims, and Hendry). The data concerned the demand for food in the US, based on a classic study by Tobin (1950) augmented with more recent data. The teams were asked to estimate the income elasticity of food demand and to forecast per capita food consumption. Hendry stepped in to refute the methodology being attributed to him. To understand why most investigators had dropped the inter-war years when modelling the demand for food in the USA, Hendry (1999) included impulse-indicator variables for all the data in that era as a ‘reverse’ Chow (1960) test (see the explanation in Salkever 1976), and found a few large outliers. Archival research revealed these corresponded to a food programme. Retaining those highly significant indicators, the equation was successfully estimated over the whole sample. As a test of its constancy, impulse-indicator variables were then added for the post-war period. Hey presto – an indicator for every observation – together with many regressors – had been fitted in two large blocks.

That discovery led to a theory for a ‘split-half’ approach to impulse-indicator saturation (see Hendry et al. 2008 and Johansen and Nielsen 2009). Consider a situation when N = T, the zt are mutually orthogonal, and the postulated model is a linear relation between yt and zt with coefficient β and a well-behaved independent Normal error. Set the significance level at α = 1/N with critical value cα. Split N into two halves of N/2 (assuming N is even for convenience). Each half can be fitted by conventional regression methods. Under the null that all the N variables are in fact irrelevant – i.e. β = 0, so we are ‘data mining’ purely for spurious significance – when fitting each half of the variables, 1/2 of a variable will be significant by chance on average using a t-test. That result follows because the probability of a draw from a t-distribution exceeding cα in absolute value is α, and hence with N/2 trials, we have α × N/2 = 1/N × N/2 = 1/2. Record any significant outcomes, and replace the first N/2 variables with the second and repeat. Again on average, 1/2 of a variable will be significant on a t-test, so combining, one variable will be retained as adventitiously significant on average despite starting with N = T.

In practice, the {zt} will be inter-correlated, the complete null of β = 0 is unlikely, as some variables will matter in any sensible specification, even if others are irrelevant, and N will not precisely equal T. These considerations suggest using multiple blocks rather than just two, mixing which combinations of variables are entered, and recording all significant findings, gradually eliminating variables that are never significant, and converging on those that are significant jointly (see Doornik 2007).

The automated model selection algorithm Autometrics (see Doornik 2009 and Doornik and Hendry 2013) can jointly handle extensive dynamics, possible outliers and structural breaks, and many forms of non-linearity. The crucial requirement is that the initial general model must nest the associated data generation process (DGP), so that all valid simplifications thereof are well-specified (congruent). The algorithm has many excellent properties as described in Castle et al. (2011). Foremost among these when N << T is that the retention rate of irrelevant variables (called the gauge) when selecting from a candidate set of variables is close to the pre-set nominal significance level α for α = min(1/N, 1/T, 1%), so that on average just αN ≤ 1 spuriously significant variables will be retained. Additional benefits are that relevant variables will be retained with roughly the same frequency (called potency) as the power of the corresponding t-tests at α in the DGP, and that bias correction after selection reduces the mean square errors of adventitiously significant irrelevant variables. These properties carry over to settings where N ≥ T.

Surely tight significance levels must lose a lot of power?

Setting α = min(1/N, 1/T, 1%) is certainly more stringent than ‘conventional’ values like 5%, when c0.05≈2. Providing near-Normality can be achieved, cα increases slowly for reductions in α, with c0.01≈2.6, and c0.001≈3.35. Focusing on c0.001≈3.35, searching across 1000 variables will on average deliver one selected spuriously, yet retain all t-statistics in excess of 3.35 in absolute value. Variables with estimated coefficients having an absolute t-statistic between about 2 and 3.35 will not be retained, but could have been at c0.05.

However, power to reject false nulls depends on the non-centrality, ψ, of the test statistic in the given sample. When ψ = 2, say, that implies that the t-distribution will have a mean of 2, and approximately a variance of unity. Consequently, 50% of the time, the observed t-statistic will be less than 2, so the power is just 0.5 at α = 0.05. Reducing α to 0.01 lowers the power to 0.28. When ψ = 3, the power rises to 0.84 at 5% and to 0.66 at 1%; and for ψ = 4 to 0.98 at 5% and 0.92 at 1%. So the power loss is low for substantive influences, albeit larger for marginally important effects.

Why does using blocks matter?

Checking large blocks, rather than single variables, matters for many reasons. First, say n of the N candidate variables were relevant in a regression. When the first is added by itself, the model is badly mis-specified by the omission of the remaining excluded n−1. The fit will be poorer, coefficient estimates will be biased for the population parameters unless all variables are orthogonal, and estimated coefficient standard errors will not correctly reflect the sampling variation.

Secondly, if two relevant variables in a regression have opposite signed coefficients, β1 × β2 < 0, and those variables are positively correlated, ρ > 0, or have an oppositely signed correlation ρ to their same-signed coefficients, then adding only one of them at a time is unlikely to detect either. This follows from elementary regression theory of ‘omitted variables bias’, as the included variable z1,t (say) has the coefficient β1 + ρβ2s, where s = σ2/σ1 is the ratio of the variables’ standard deviations. The coefficient of z1,t in the simple model will almost always be smaller than that in the joint model; and similarly for z2,t, so neither may be detected in isolation even if jointly they are significant. This idea extends to when several variables effectively cancel each other in isolation, but not jointly. Obvious settings of relevance in economics are when z1,t and z2,t enter the DGP as a difference or a differential; or are part of a cointegrating relationship.

Thirdly, there is an important distinction between detecting large residuals, which are those not accounted for by the included variables, and detecting outliers using a search procedure. An unmodelled large location shift greatly increases the residual standard deviation, which is the usual benchmark for judging outliers, so no large residuals need be found. Thus, single-step expanding searches have zero power to detect such a shift by adding just one indicator, unless the timing and form of the shift are already known. However, by adding large blocks of indicators, multiple outliers and shifts can be detected (see Castle et al. 2012).

Won’t ‘false positives’ swamp relevance in ‘Big Data’?

A ‘fat’ big-data set is one with many variables but not so many observations, so N > T and N is large. There are 2N possible combinations of t-statistics being significant or not by chance under the null for N candidate variables. For N = 10,000, say, that leads to more than 103000 events, which is unimaginably large. It is understandable why there is a belief that results may be swamped by false positives, as it is clearly a serious danger unless significance levels are appropriately set (see Harford 2014). However, when α = 0.0001, despite N = 10,000, one variable will be found significant when none matters. Thus, some control is possible for economics, where N = 10,000 would be very large, yet only require c0.0001 ≈4 (under Normality). For much larger N, say several million, the probability of a t-statistic exceeding 6 under the null is about 2 × 10−7 (using a Normal approximation – see Selby 1970: 933), so even when N = 5, 000, 000, that significance level delivers αN≈1. If the variable in question was relevant, a non-centrality of ψ = 6 would deliver a 50% probability of significance, and ψ = 9 would virtually ensure significance. The ‘hay stack’ may be enormous, but large needles can still be found without too much confusion with straw.

Can good theory ideas be retained?

Indeed, there is a more efficient approach when a theory correctly specifies a subset z1,t of n variables as relevant. These can be orthogonalised with respect to the rest, z2,t, even when N > T, by dividing the latter into feasible sub-blocks, estimating separate regressions for each, and replacing each subset of z2,t by their residuals vt. Thus, the n variables can be retained without selection at every stage, only selecting over the putative irrelevant variables vt at a stringent significance level. Under the null hypothesis of the theory being complete and correct, selection over the N−n other variables has no impact on the estimated coefficients of the relevant variables, or their distributions (see Hendry and Johansen 2014). When the initial theory specification is incomplete, but the enlarged set of variables nests the DGP, then an improved model will result. In this combined theory- and data-driven approach, it is almost costless to check the relevance of even large numbers of candidate variables, with potentially valuable benefits of discovering a better empirical model when the theory is incomplete or incorrect.

Can we rely on using Normal critical values?

The critical values described above need near-Normality, which may seem demanding in many settings, and cα would need to be larger in its absence. Fortunately, there is a virtuous circle operating. A multiple block-search algorithm can allow impulse-indicator saturation to be carried out, which will remove the impact of outliers and shifts, and so leave a near-Normal residual. Castle et al. (2012) provide evidence in a setting where the error is drawn from a Student’s t distribution with 3 degrees of freedom, which has no finite moments beyond its variance.

When data are integrated, larger critical values than Normal are needed for testing the reduction to a non-integrated representation. As Sims et al. (1990) show, provided the model is specified with sufficient lags on all variables in its integrated specification, a reduction to a non-integrated representation is the only hypothesis where non-Normal critical values are required. While the lagged dependent variable is unlikely to be dropped, eliminating the last lag of an irrelevant integrated variable during selection entails an integration reduction, so larger critical values are needed – one reason for the tight significance levels proposed above.

Are there ‘real world’ examples selecting when N > T ?

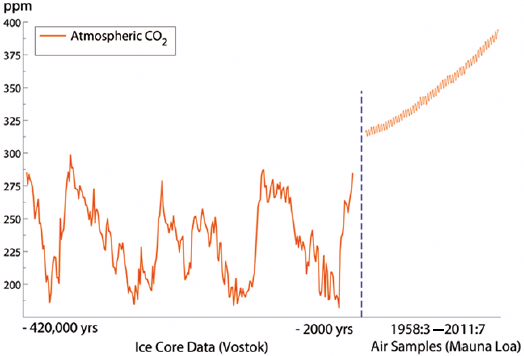

Figure 1 shows a remarkable time series of atmospheric CO2 with historical data measured by ice cores, and more recent data taken from records measured at Mauna Loa, exhibiting pronounced seasonal and trend movements. Hendry and Pretis (2013) model the latter data by identifying natural and anthropogenic contributions to atmospheric CO2 from a general model with more than 480 candidate explanatory variables based on about 250 monthly observations, simplified by Autometrics to models with fewer than 20 regressors.

Figure 1. Atmospheric CO2 levels

Vegetation, temperature, and other natural factors like Southern Oscillation were necessary, but not sufficient, to explain the growth in CO2. Industrial production components, driven by business cycles and economic shocks, were highly significant contributors, and their cumulation alone accounted for the growth in atmospheric CO2, as the freely selected equations retained neither intercepts nor deterministic trends.

In Castle and Hendry (2014a), initial general models had around 170 candidate variables, including step indicators, for 140 observations. Selection crucially revealed a small but substantive location shift pre- and post-World War II, lifting the mean growth rate of real wages from under 1% pa to almost 2% pa, as well as a non-linear reaction of real wages to unemployment, leading to a much better specification (see Castle and Hendry 2014b for a summary).

As Hendry and Mizon (2014a) show, a failure to model distributional shifts leads to the breakdown of many standard macro models. ‘Sensible data mining’, in which location shifts are jointly modelled with the theory using techniques such as impulse-indicator saturation, guard against such failures (see Hendry and Mizon 2014b for a summary).

Is this approach computationally feasible for very large N ?

Autometrics is a tree-search algorithm selecting congruent, parsimonious, encompassing representations. Implicitly, all 2N possible models need checking, which becomes infeasible for large N. If N=100, estimating 109 models per second would take 106 times the age of the universe to estimate all possible models, so a ‘brute force’ approach is impractical. However, shortcuts can be made. When all candidate variables are mutually orthogonal, as with impulse indicators, a 1-cut approach can be used as follows. For T > N, fit the general model, and retain all variables whose coefficients are significant at the desired level, eliminating all others. There is no search, and no ‘repeated testing’. When there are N > T inter-correlated candidate regressors {zt}, one approach would be to transform to their principal components {ut} say, which are mutually orthogonal. When non-linearities may also matter, powers and exponentials of the ui,t can be used as discussed in Castle and Hendry (2014a), partially orthogonalised by demeaning. Selection can then be undertaken in successive feasible 1-cut stages using a loose α, tightened when sub-selections are combined for later choices. Possible circumventing strategies for very large N include using non-statistical criteria to restrict the variables to be selected over; and searching over sub-units separately. For impulse-indicator saturation alone, sub-samples of T could be explored and later combined, with care if shifts have occurred across splits.

Conclusions

Appropriately conducted, data mining can be a productive activity even with more candidate variables than observations. Omitting substantively relevant effects leads to mis-specified models, distorting inference, which large initial specifications should mitigate. Automatic model selection algorithms like Autometrics offer a viable approach to tackling more candidate variables than observations, controlling spurious significance.

References

Campos, J and N R Ericsson (1999), “Constructive data mining: Modeling consumers’ expenditure in Venezuela”, Econometrics Journal, 2: 226–240.

Castle, J L, J A Doornik, and D F Hendry (2011), “Evaluating automatic model selection”, Journal of Time Series Econometrics, 3(1).

Castle, J L, J A Doornik, and D F Hendry (2012), “Model selection when there are multiple breaks”, Journal of Econometrics, 169: 239–246.

Castle, J L and D F Hendry (2014a), “Semi-automatic non-linear model selection”, Chapter 7 in N Haldrup, M Meitz, and P Saikkonen (eds.), Essays in Nonlinear Time Series Econometrics, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Castle, J L and D F Hendry (2014b), “The real wage–productivity nexus”, VoxEU.org, 13 January.

Castle, J L and N Shephard (eds.) (2009), The Methodology and Practice of Econometrics, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chow, G C (1960), “Tests of equality between sets of coefficients in two linear regressions”, Econometrica, 28: 591–605.

Denton, F (1985), “Data mining as an industry”, Review of Economics and Statistics, 67: 124–127.

Doornik, J A (2007), “Econometric model selection with more variables than observations”, Working paper, Economics Department, University of Oxford.

Doornik, J A (2009), “Autometrics”, in Castle, and Shephard (2009): 88–121.

Doornik, J A and D F Hendry (2013), Empirical Econometric Modelling using PcGive: Volume I, 7th ed., London: Timberlake Consultants Press.

Friedman, M (1940), “Review of Tinbergen (1939)”, American Economic Review, 30: 657–650.

Gilbert, C L (1986), “Professor Hendry’s econometric methodology”, Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 48: 283–307.

Harford, T (2014), “Big data: are we making a big mistake?”, FT Magazine, 28 March.

Hendry, D F (1999), “An econometric analysis of US food expenditure, 1931–1989”, in J R Magnus, and M S Morgan (eds.), Methodology and Tacit Knowledge: Two Experiments in Econometrics, Chichester: John Wiley and Sons.

Hendry, D F and Doornik, J A (2014), Empirical Model Discovery and Theory Evaluation, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Hendry, D F and S Johansen (2014), “Model discovery and Trygve Haavelmo’s legacy”, Econometric Theory.

Hendry, D F, S Johansen, and C Santos (2008), “Automatic selection of indicators in a fully saturated regression”, Computational Statistics, 33: 317–335. Erratum: 337–339.

Hendry, D F and G E Mizon (2014a), “Unpredictability in economic analysis, econometric modelling and forecasting”, Journal of Econometrics, 182: 186–195.

Hendry, D F and G E Mizon (2014b), “Why DSGEs crash during crises”, VoxEU.org, 18 June.

Hendry, D F and F Pretis (2013), “Anthropogenic influences on atmospheric CO2”, in R Fouquet (ed.), Handbook on Energy and Climate Change, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar: 287–326.

Hoover, K D and S J Perez (1999), “Data mining reconsidered: Encompassing and the general-to-specific approach to specification search”, Econometrics Journal, 2: 167–191.

Johansen, S and B Nielsen (2009), “An analysis of the indicator saturation estimator as a robust regression estimator”, in Castle and Shephard (2009): 1–36.

Leamer, E E (1983), “Let’s take the con out of econometrics”, American Economic Review, 73: 31–43.

Lovell, M C (1983), “Data mining”, Review of Economics and Statistics, 65: 1–12.

Salkever, D S (1976), “The use of dummy variables to compute predictions, prediction errors and confidence intervals”, Journal of Econometrics, 4: 393–397.

Selby, M S (ed.) (1970), Handbook of Tables for Mathematics, Cleveland, Ohio: The Chemical Rubber Co.

Sims, C A, J H Stock, and M W Watson (1990), “Inference in linear time series models with some unit roots”, Econometrica, 58: 113–144.

Spanos, A (2000), “Revisiting data mining: ‘Hunting’ with or without a license”, Journal of Economic Methodology, 7: 231–264.

Tinbergen, J (1940), Statistical Testing of Business-Cycle Theories, Vol. II: Business Cycles in the United States of America, 1919–1932, Geneva: League of Nations.

Tobin, J (1950), “A statistical demand function for food in the U.S.A.”, Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, A, 113(2): 113–141.