The basics of economics teach us that price caps – setting a maximum price for a given product – are not a good idea: they distort demand and discourage producers from supplying the market. So why did the Biden administration, led by US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, a seasoned economist, advocate capping oil prices from Russia after the invasion of Ukraine in 2022? The answer is that this price cap, introduced for Russian crude oil in December 2022 and petroleum products originating in the country in February 2023, differs significantly from the standard ceiling discussed in the introductory economics class.

A nascent literature analyses this brand-new policy instrument. In a recent paper, Babina et al. (2023) use customs data to provide evidence of the effectiveness of the cap imposed by the G7 on Russia. Salant (2023), Gars et al. (2023), and Johnson et al. (2023a) offer theoretical models, focusing on different features of the policy. In a recent paper, we assess the effectiveness of the policy so far (Johnson et al. 2023b).

Energy: A double-edged sword

Russia’s abundance of natural resources, mainly fossil fuels, is a double-edged sword, both for the government and for the rest of the world. On the one hand, energy exports are the most important source of income for the Russian state, which creates a vulnerability. On the other, the world economy relies on Russian energy exports. In 2021, before the war, Russia produced about 10.5 million barrels per day and exported nearly 8 million, making it the world’s largest exporter of oil and products combined. This dependence of the world economy on Russian energy exports – especially in 2022, when major economies faced post-Covid-19 supply constraints and inflation was at a 30-year high – has made energy exports a powerful economic weapon for Russia.

Russia’s dominance of global energy markets has created the need for new solutions. The price cap on Russian oil emerged as a policy to meet this challenge.

Objectives and structure of the price cap

The price cap has two main objectives. First, it is an integral part of a broader sanctions package aimed at reducing Russia’s foreign exchange income and reducing its ability to wage war in Ukraine. The second purpose was to allow Russian oil to remain on the world market in the face of the impending total embargo of the EU and the ban on services.

The price cap on Russian oil is being implemented by the G7 countries and their allies. It is a coalition of service providers. Before the invasion, about 90% of Russian oil trade was based on Western services, mainly tankers and insurance. The price limit introduces a ceiling on the price of Russian oil which uses such Western services when leaving Russia. In practice, the price cap is implemented through regulations. A system of attestations, issued by trusted entities, is used to enforce compliance.

What is the difference between the price limit of Russian oil and standard price ceilings?

The standard price cap applies to all commodities traded on a given market. For example, in some countries there are price limits on bread for everyone, diesel for farmers, or rent controls for housing. Such ceilings often lead to excessive demand for goods and insufficient supply, and thus to shortages at a limited price. If prices are limited, other non-price mechanisms, such as ‘first come, first served’, are required to allocate the good. Too often, the result is empty bakery shelves, fuel shortages, or difficulty finding housing.

The price ceiling of Russian oil differs from the standard price ceiling in several important ways. First, it only limits the price received by one supplier – Russia. Essentially, the cap shifts revenues from a sanctioned entity – in this case, the Kremlin – towards resource buyers who can buy crude oil below the benchmark price on the world market. This is an advantage and not a disadvantage of this instrument: as long as the oil reaches the world market and the revenues accrued to the sanctioned country are limited, the key objectives are achieved.

The second reason why this price cap differs from the standard caps is that Russia is an infra-marginal producer, which means that its marginal costs of extracting and transporting oil for export are much lower than the settlement prices of the market. The consequence is that it is possible to set a price ceiling above Russia’s cost of extraction, but still well below world prices.

Concerns and criticism

The proposal to introduce the price cap policy was met with an uproar, and some prominent Western voices expressed scepticism. Before the introduction of the price cap, the main fear was that Russia would refuse to export oil at limited prices, effectively turning the price cap into an embargo. In July 2022, JP Morgan predicted that oil prices would rise to more than $350 a barrel when Russia refused to sell within the price cap. The message from the Kremlin added weight to these fears. Today we know that these were empty words. Russia has increased its exports and market prices remain stable. Economics allows us to understand why.

Russia’s economic incentives to sell below the price limit depend on the level of the limit. With the ceiling set at $60 – well above even the highest estimates of the marginal cost of extracting Russian oil, which various studies estimate to be around $10–20 per barrel – extracting and exporting oil are still very lucrative. These incentives are exacerbated by the financial and trade constraints facing the Russian state. These restrictions mean that access to cash is now particularly important for Russia. It may turn out that, paradoxically, Russia prefers to increase production if the price it receives for oil is lower.

A drastic reduction in imports would push the price up, allowing Russia to sell smaller quantities at higher prices. Research shows, however, that with the currently low possibilities of replacing Western services with services from China or other countries, this move would simply be unprofitable, even if the cap were lowered to $30 per barrel.

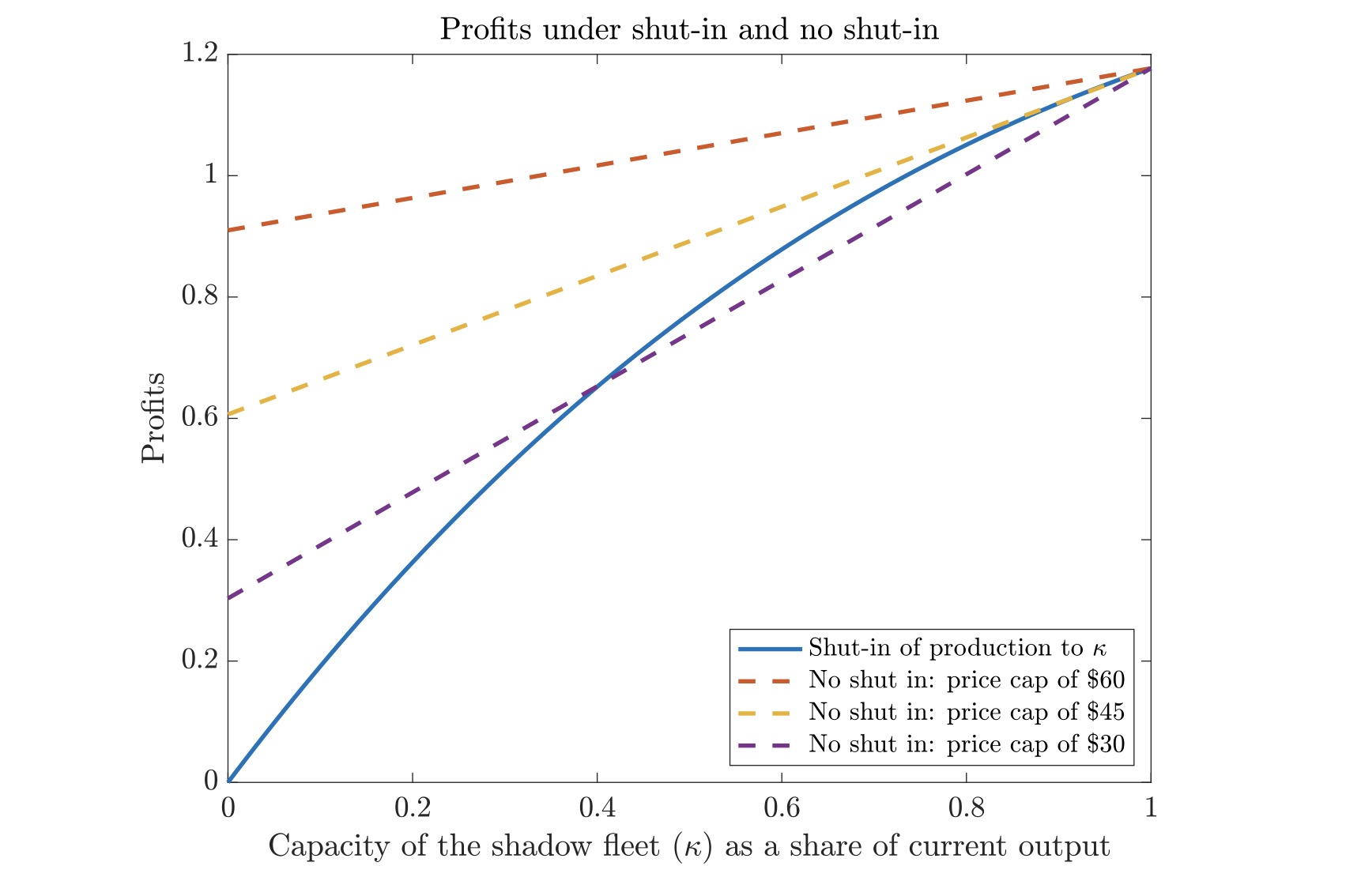

Figure 1 uses a simple model to simulate profits under the shut-in and no-shut-in options, as a function of the capacity of the ‘shadow fleet’ – Russia’s ability to sell outside of the price cap regime. It assumes that the marginal cost is $15 per barrel. The solid line shows profits when production is shut in, and the dashed lines show profits from continuous sales under the cap. We consider three price cap levels: the current $60, as well as $45 and $30.

Figure 1 Profits in the shut-in and no-shut-in scenarios

The solid line is above the dashed only when the cap is $30 per barrel and when own services capacity is large. Thus the main takeaway from this analysis is that, for the parameter values we assumed, shut-in is never profitable when the cap is $60 or even when it is $45, and is unlikely to be profitable if the cap was set at $30 per barrel.

Another common criticism of the price cap was that other countries would not join the coalition. This opinion does not take into account the fact that it is a coalition of service providers, and other countries – for example, India or China – do not have to officially join the coalition. For it to be effective, it is enough for private companies from these countries to buy cheap oil from Russia.

Price cap assessment so far

Contrary to ominous forecasts, setting the price cap for Russian oil at $60 per barrel appears to have four broad effects.

- Studies show that the Kremlin’s oil-related revenues fell by 49% compared to the period March-November 2022 and by 23% compared to the period from January 2021 to January 2022.

- Oil production in Russia has increased, not decreased.

- The introduction of the EU embargo has not caused global oil prices to rise, but has even stabilised prices.

- Most Western service providers remain engaged in trade with Russia.

There are still legitimate concerns. Contrary to initial expectations, the oil price ceiling has not been lowered, and some coalition members have expressed dissatisfaction with the current level of $60 per barrel. There are also signs that some traders are not honest about the attestation process. Analysis (and political will) is needed to tighten attestation and security.

The price cap on Russian oil reflects a novel approach to sanctions, and the world is only beginning to understand its impact on Russian oil revenues, geopolitical movements, and the commodity market. However, this instrument already shows that even the largest producer of the necessary raw material does not go unpunished.

References

Babina, T, B Hilgenstock, O Itskhoki, M Mironov, and E Ribakova (2023), “Assessing the impact of international sanctions on Russian oil exports”, mimeo.

Gars, J, D Spiro, and H Wachtmeister (2023), “The price cap on Russian oil: A quantitative analysis”, mimeo.

Johnson, S, L Rachel, and C Wolfram (2023a), “A theory of price caps on non-renewable resources”, NBER Working Paper 31347.

Johnson, S, L Rachel, and C Wolfram (2023b), “Design and implementation of the price cap on Russian oil exports”, Journal of Comparative Economics, in print.

Salant, S W (2023), “Targeted price ceilings in competitive models”, mimeo.