Tax collection is a critical development challenge. Low-income countries raise less revenue as a share of GDP than high-income ones. They also derive a larger share of their revenues from trade taxes, which are easier to enforce than more sophisticated taxes such as value-added or income taxes which are prominent sources of revenue in high-income countries (Baunsgaard and Keen 2010, Cagé and Gadenne 2018, Besley and Persson 2014).

Tariff enforcement, however, is challenging because it requires verifying which products are imported from what country in order to (1) identify the applicable tariff rate and (2) assess their value to determine the tax base. Existing studies proxy tariff evasion with ‘trade gaps’, product-level discrepancies between yearly exports reported by the source country and import values recorded in the destination country (following Fisman and Wei 2004). Such analysis of trade gaps has proven to be a useful diagnostic tool to detect the prevalence of tariff evasion in different countries and the risks associated with different types of products (Mishra et al. 2008, Javorcik and Narciso 2008, Jean and Mitaritonna 2010, Vezina and Rotunno 2010). However, it does not allow precise quantification of the taxes evaded (Levinson and Kellenberg 2016) nor of the importance of different channels for evasion (value undervaluation or product misclassification). Most importantly, it offers only limited help identifying which transactions are most at risk of evasion, information that is central to the design of anti-evasion policies.

To answer these questions, in a recent paper (Anne et al. 2023), we match detailed export transaction data from France with import transaction data from Madagascar using container identifiers to study tariff evasion. Unique detailed information on transport costs – external freight costs, insurance costs, and other charges – allows us to make export and import values directly comparable. For a given container, we are able to construct a measure of (shipment level) reporting discrepancies comparing the value reported and the (HS) products declared in official records from two administrative sources, the exporter declaration submitted to French customs and the importer declaration submitted to and cleared by the Madagascan customs. Information on the tariff duties paid by the importer makes it possible to assess the loss in tariff revenue.

Reporting discrepancies are highly prevalent and driven by tariff evasion

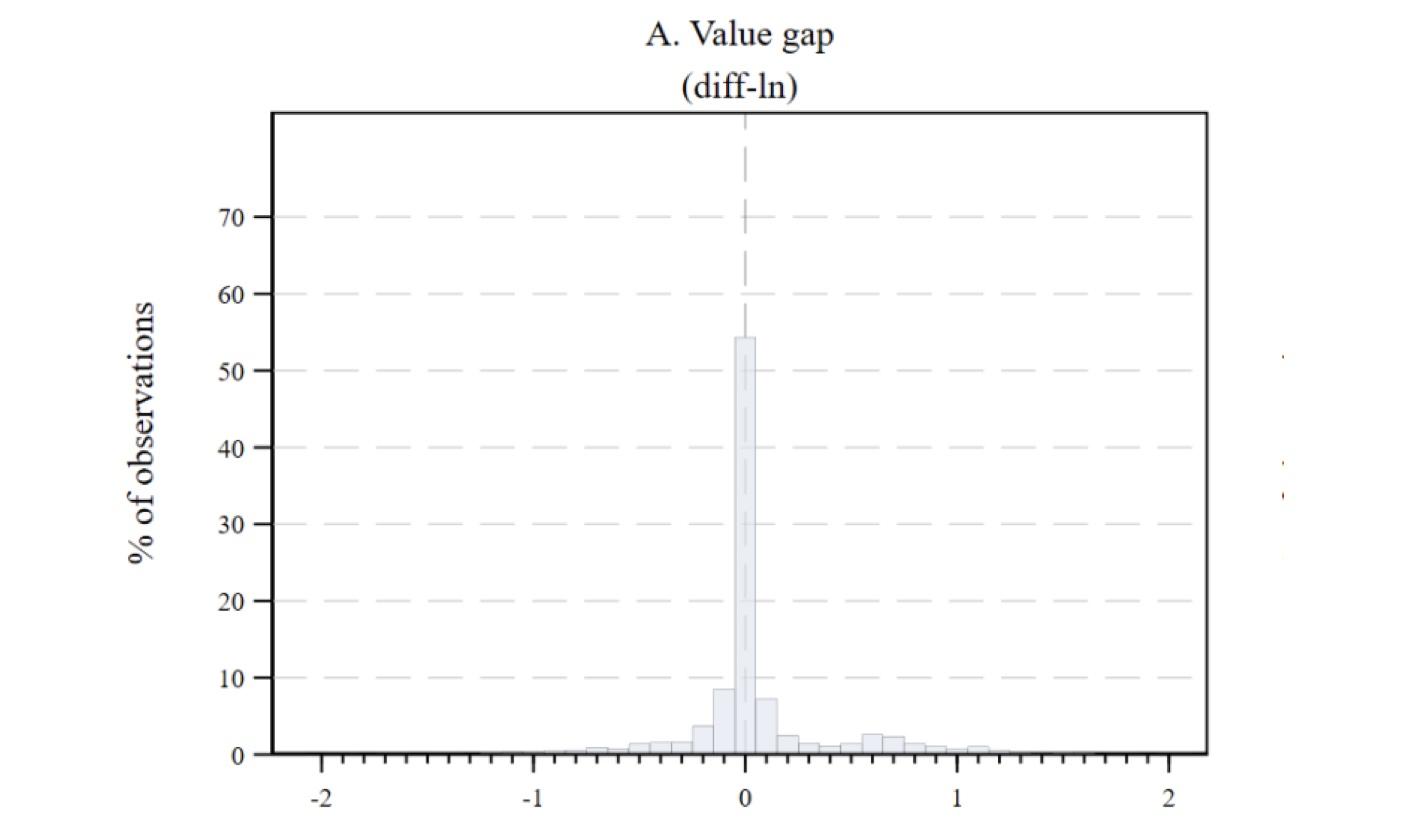

Reporting discrepancies are highly prevalent but small on average. For the average container, the export value recorded in France exceeds the import value recorded in Madagascar by 6%. This small average, however, hides the prevalence of reporting discrepancies: 47% of containers have value gaps that exceed 5% in absolute value (21% have a negative gap under 5% and 26% have a positive gap exceeding 5%) (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Logarithm difference between declared export and import values (value gaps)

Product misclassification is also pervasive. Containers with correct product classification account for only half of all containers (49%). However, most instances of misclassification do not appear strategic, as they do not result in a lower tariff burden: only 19% of containers feature tariff-decreasing misclassification, while 31% feature neutral or tariff-increasing misclassification.

To what extent are these discrepancies related to tariff evasion?

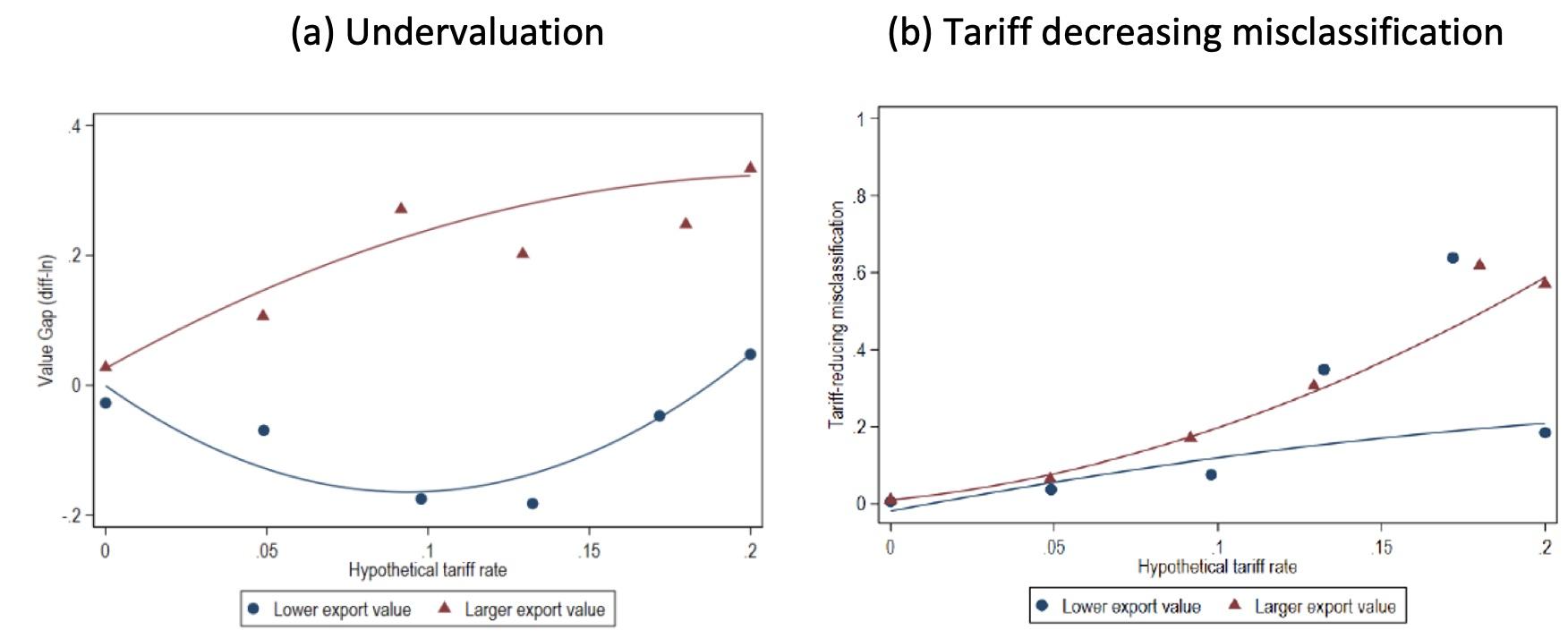

There are many innocuous reasons for discrepancies, such as differential reporting systems, exchange rate fluctuations and the way transport and insurance costs are accounted for (or not). Yet, value gaps increase with the tariff rates faced by the importer, especially for higher export-value shipments (Figure 2a). The customs values are thus the most underreported for containers with the most at stake (i.e. subject to higher tariffs) and for which the export value is higher, consistent with the premise that discrepancies are informative about tariff evasion.

The same pattern holds for product misclassification resulting in reduced tariff revenues (Figure 2b). Value gaps are also correlated with scores for fraud risk and proxies for corruption risk (Chalendard et al. 2023).

Figure 2 Undervaluation and tariff-decreasing misclassification increase with tariffs

Quantifying tariff revenue losses for Madagascar

We quantify the impact of reporting discrepancies on aggregate tariff revenues by constructing a novel container-level measure of the tariff revenue gap. It is defined as the difference between the duties actually paid by the importer and the duties that would have been paid had the duties been applied to the products and values listed in the matched French export declaration. The median tariff revenue gap per container is null (€0) but this masks large aggregate tariff revenue losses, because value gaps and product misclassifications are concentrated in high-tariff, high-export value containers. The average discrepancy between reported imports and exports for a given container represents a tariff revenue loss equal to 24% of the tariff paid.

Turning to the channel for tariff evasion, we find that undervaluation accounts for 67% of tariff revenue gaps while the remaining (33%) comes from misclassification. Containers with tariff-decreasing product misclassification are the main source of lost tariff revenues, and such containers account for 82% of lost revenues. However, even for containers with misclassified products, a significant share of the tariff revenue losses is due to undervaluation and not product misclassification per se. Decomposing the tariff revenue gaps shows that import undervaluation accounts for 67% of tariff evasion while misclassification is responsible for the remaining 33%.

The granularity of tariff evasion

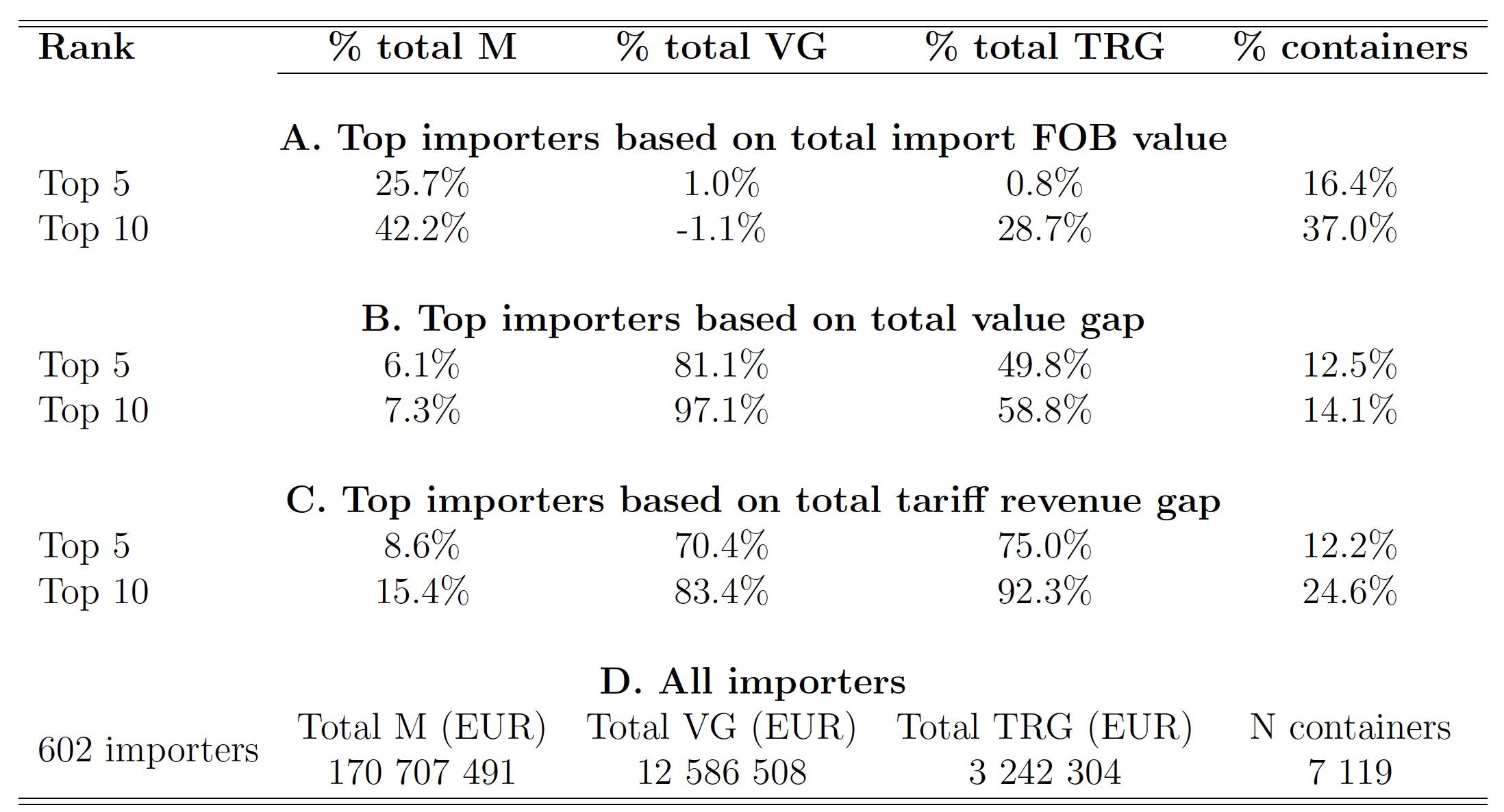

Value gaps are concentrated among a few Madagascan importers, as is shown in Table 1. The top five importers (out of more than 600 importers in our sample) account for 75% of the aggregate tariff revenue losses. This finding underscores the granularity of tariff evasion. Interestingly, evasion does not appear to be concentrated among the largest importers in terms of value: the top ten firms in terms of total tariff revenue gaps account for only 15% of total imports.

Table 1 Concentration of gaps among Madagascar’s top importers

Note: Importers without a tax identifier are excluded from the sample.

Tariff enforcement is poor

Last but not least, our data also enable us to assess the effectiveness of customs in mitigating tariff evasion. Overall, controls in Madagascar appear poorly targeted and ineffective: value adjustments by customs inspectors reduce tariff losses by only 1.8% and are only weakly correlated with value gaps. This may be due to the difficulty of both predicting and proving tax evasion, but it may also be consistent with corruption.

Concluding remarks

Tariff evasion in low-income countries that rely heavily on taxes collected at the border, like Madagascar, significantly reduces government revenues. The fact that evasion is highly concentrated among a few importers suggests that focusing enforcement efforts on a handful of firms could have sizeable macro-fiscal implications.

From an operational perspective, our study also underscores the promise of information sharing between customs authorities. By providing real-time transaction-level information from their customs IT systems, major exporting countries can play an important role in helping low-income countries improve their tax-to-GDP ratios by fighting more effectively customs evasion.

References

Anne, C, C Chalendard, A M Fernandes, B Rijkers and V Vicard (2023), “Containing tariff evasion”, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 10606.

Chalendard, C, A M Fernandes, G Raballand and B Rijkers, (2023), “Corruption in customs,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 138(1): 575–636.

Baunsgaard, T, and M Keen (2010), “Tax revenue and (or?) trade liberalization”, Journal of Public Economics 94 (9-10): 563-577.

Besley, T, and T Persson (2014), “Why do developing countries tax so little?”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 28(4): 99-120.

Cagé, J, and L Gadenne (2018), “Tax revenues and the fiscal cost of trade liberalization, 1792-2006”, Explorations in Economic History 70: 1-24.

Fisman, R, and S J Wei (2004), “Tax rates and tax evasion: evidence from “missing imports” in China”, Journal of Political Economy 112(2): 471-496.

Javorcik, B S and G Narciso (2008), “Differentiated products and evasion of import tariffs”, Journal of International Economics 76(2): 208-222.

Jean, S, and C Mitaritonna (2010), “Determinants and pervasiveness of the evasion of customs duties”, CEPII Discussion Paper.

Levinson, A, and D Kellenberg (2016), “The trade data gap: Mistakes and malfeasance”, VoxEU.org, 21 October.

Mishra, P, A Subramanian and P Topalova (2008), “Tariffs, enforcement, and customs evasion: evidence from India”, Journal of Public Economics 92(10-11): 1907–1925.

Vezina, P L, and L Rotunno (2010), “Chinese networks and tariff evasion”, VoxEU.org, 24 Nov.