From March 2020, 188 countries closed schools temporarily to prevent the spread of COVID-19, causing approximately 1.5 billion students to lose the opportunity to receive an in-person formal education (OECD 2021, UNESCO 2021) during that period. In Japan, elementary, junior high, and high schools, as well as schools for special needs education, were temporarily closed nationwide from 2 March 2020, but in-person classes resumed three months later, at the beginning of June, even in areas where the COVID-19 infection situation was severe.

More than two years after the school closures began in March 2020 (as of October 2022), studies have shown that the temporary closure of schools due to COVID-19 has worsened student academic performance in many countries and regions (Engzell et al. 2021, Gore et al. 2021, Kuhfeld et al. 2020, Maldonado and De Witte 2022, Tomasik et al. 2021) Furthermore, in Japan, Doi et al. (2021) found that the closure of pre-schools worsened the non-cognitive abilities of pre-school children.

The effects of COVID-19 school closures varied among students. For example, students from disadvantaged schools and residential areas (Agostinelli et al. 2020, Gore et al. 2021, Maldonado and De Witte 2021), students with low parental educational attainment (Engzell et al. 2021), students with lower academic achievement during the pandemic (Clark et al. 2021), and relatively younger students (Tomasik et al. 2021) experienced greater decline in academic performance.

On the other hand, shorter periods of school closure have a smaller impact on student achievement (Hallin et al. 2022, Halloran et al. 2021). For example, focusing on 3rd to 8th graders in 12 US states, Halloran et al. (2021) found that while COVID-19 school closures reduced pass rates on state-wide achievement tests, earlier return to in-person classes mitigated the decline in academic achievement for schools that were able to do so. In Sweden, where no temporary school closures took place, Hallin et al. (2022) found that the reading comprehension (word decoding and reading comprehension scores) of 97,073 1st to 3rd graders did not decline due to the COVID-19 shock alone.

Existing studies have shown that COVID-19 school closures reduce students' cognitive and non-cognitive skills, but that students' academic performance recovers with time after the resumption of in-person classes. However, three questions remain unresolved. First, since most existing studies use annual surveys, it remains unclear when and to what extent academic performance recovered after the resumption of in-person classes. Second, it is unclear whether the impact of the COVID-19 school closure on academic performance differed depending on student living conditions at the time. Third, the effect of the school closures on the non-cognitive abilities of elementary school students who are older than the pre-school children analysed by Doi (2021) remains unexamined.

To answer these three questions, we analysed the long-term effects of school closure on elementary school students' cognitive and non-cognitive skills in Nara City, Japan, with a population of 350,000 (Asakawa and Ohtake, 2022). Furthermore, we tested whether the impact of the COVID-19 school closure on cognitive and non-cognitive skills differed depending on the living conditions during and after the school closure.

For cognitive skills, we used data from the Manabi-Nara maths test, which is conducted three times a year (in March, July, and December) for 4th to 6th graders in all public elementary schools in Nara City (approximately 2,600 students in each grade). This test is designed to be of the same difficulty level each year, allowing for comparisons of cognitive skills at the same grade between different cohorts. We used five school terms for students who experienced COVID-19 school closure (grades 4 and 5 as of March 2020) from December 2019 to March 2021. In order to account for academic growth in the absence of school closure, this study used data from December 2019 to March 2021 for students who were in the 4th and 5th grades in March 2020 (treatment group), and data from December 2017 to March 2020 for students who were in the 6th grade in March 2020 (control group), and estimated the average treatment effect on the treated (ATT) per school-term, using a difference-in-differences (DID) analysis.

For non-cognitive skills, we used the results of the Student Survey, which is conducted once a year (in December) in conjunction with Manabi-Nara test. Specifically, we used ten questions regarding "attitudes toward proactive learning in maths" (often asking questions to the teacher in maths class, appropriate homework behaviour, etc.) and created non-cognitive skill dummies that take 1 for "applies/somewhat applies." We also used DID to estimate the change from 5th to 6th grade in the non-cognitive skills before and after the COVID-19 school closure between students who experienced the school closure (5th graders in December 2020) and those who did not experience the school closure (5th graders in December 2019).

To examine the heterogeneity of school closure effects depending on living conditions during and after the COVID-19 school closure, we created individual dummy variables for ten items on living conditions (lack of food, lack of sleep, lack of study, no passion, feeling unsafe, etc.). We estimated the effects of these living condition dummies on cognitive and non-cognitive skills by item, and calculated the average treatment effect per school-term conditioned on students' living conditions (CATE) by summing the effects of the ten living conditions.

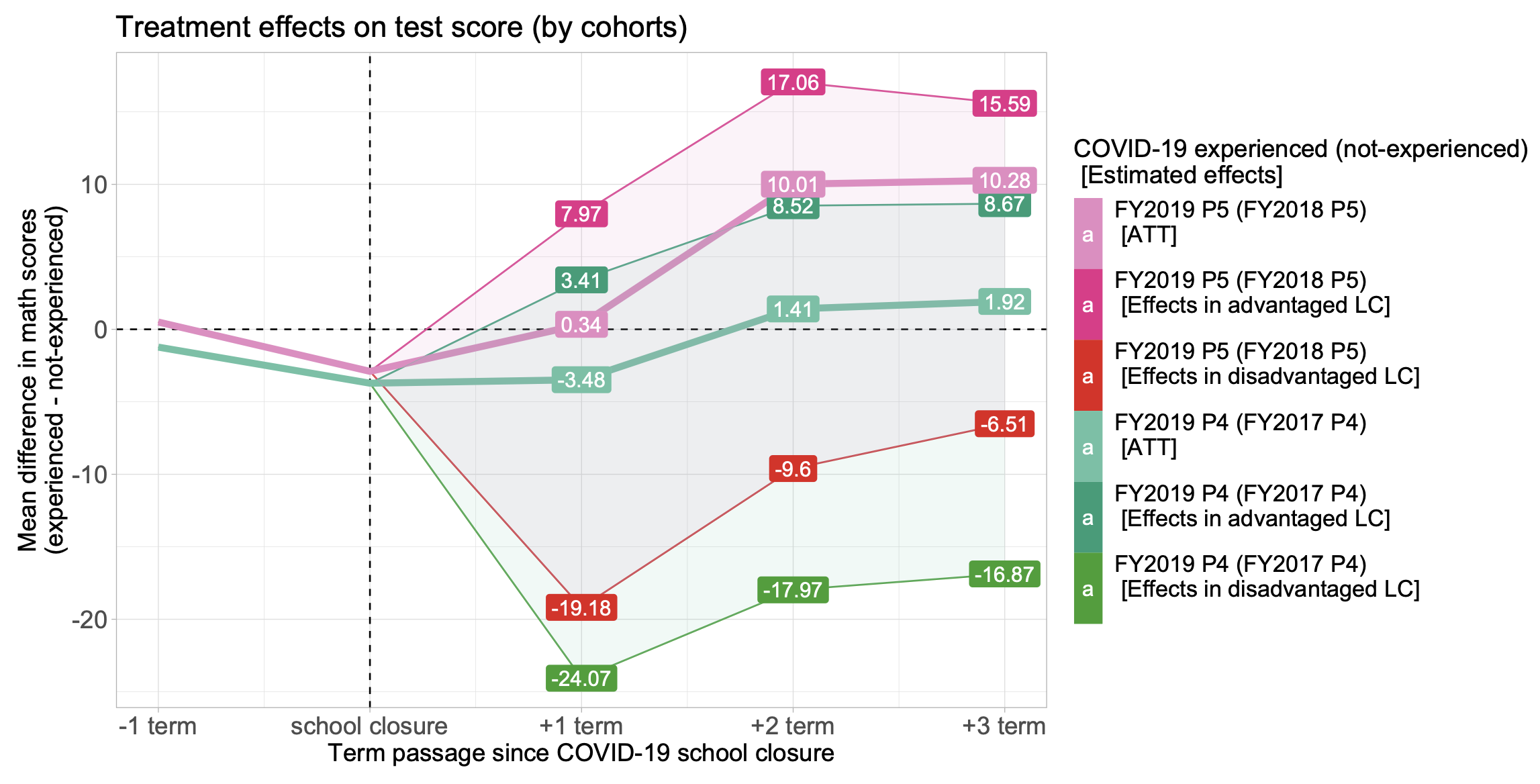

The analysis yielded four strands of evidence regarding cognitive skills (Figure 1). First, in March 2020, students' maths scores declined by about 2.3 points (20–24 standard deviations) in the short term. Second, after July 2020, the test scores of 5th graders in March 2020 recovered faster (10 points, 20–22 standard deviations) than 4th graders (1.41–1.92 points, 20–22 standard deviations). Third, the COVID-19 school closure's effects differed by up to 27 points depending on the quality of living conditions during and after the school closure. Fourth, the difference in the effect of living conditions on test scores was highest in students who scored below the 25th percentile.

Figure 1 Treatment effects on maths test scores

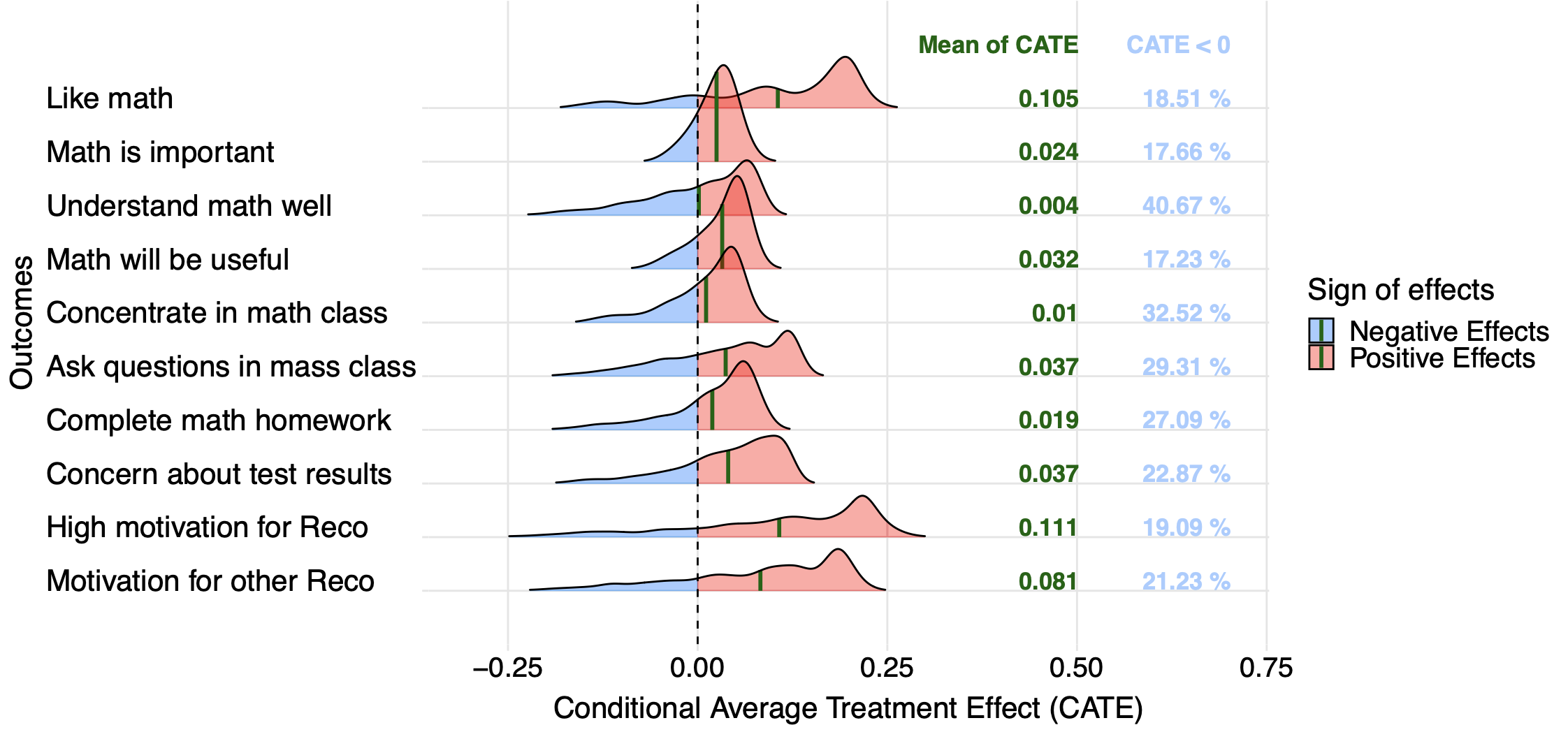

Three strands of evidence were obtained for non-cognitive skills (Figure 2). First, all non-cognitive skills increased on average after the COVID-19 school closure ended. Second, the school closure's effects on attitudes toward proactive learning in maths varied depending on the quality of living conditions during and after the closure; adverse effects remained for about 40% of students even six months after the school closure. Third, the difference in the impact of school closure due to living conditions was highest in students below the 25th percentile in terms of cognitive skills.

Figure 2 Treatment effects on non-cognitive skills

Following the spread of COVID-19, schools and parents in many countries and regions implemented various efforts to compensate for the loss of in-person classes due to the COVID-19 school closure. At school, long vacations and school events were reduced or eliminated (Asakawa and Ohtake 2022) and at home, parents increased their time and resource investments in private education (Bansak and Starr 2021).

Our findings can be applied in analysing the impact of school closures due to infectious diseases other than COVID-19 (Meyers and Thomasson 2021, Oikawa et al. 2022) and due to natural disasters (Andrabi et al. 2020, Goodman 2014, Sacerdote 2012). Another contribution is the elucidation that lower academic achievement and student scores resulted in further disparities in cognitive and non-cognitive abilities due to COVID-19 school closure.

To ensure that no students are left behind in periods when the normal operation of schools is difficult, the government should provide generous support for younger students and those with lower academic levels, and those with disadvantaged living conditions.

Editor’s note: The main research on which this column is based (Asakawa and Ohtake 2022) first appeared as a Discussion Paperof the Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI) of Japan.

References

Agostinelli, F, M Doepke, G Sorrenti and F Zilibott (2020), “When the great equalizer shuts down: schools, peers, and parents in pandemic times”, NBER Working Paper No. 28264.

Andrabi, T, B Daniels and J Das (2020), “Human capital accumulation and disasters: evidence from the Pakistan earthquake of 2005”, Journal of Human Resources.

Asakawa, S and F Ohtake (2022), “Impact of COVID-19 School Closures on the Cognitive and Non-cognitive Skills of Elementary School Students”, RIETI Discussion Paper No. 22075.

Bansak, C and M Starr (2021), “Covid-19 shocks to education supply: how 200,000 US households dealt with the sudden shift to distance learning”, Review of Economics of the Household 19(1): 63-90.

Clark, A E, H Nong, H Zhu and R Zhu (2021), “Compensating for academic loss: Online learning and student performance during the COVID-19 pandemic”, China Economic Review 68, 101629.

Doi, S, K Miyamura, A Isumi and T Fujiwara (2021), “Impact of school closure due to COVID-19 on the social-emotional skills of Japanese pre-school children”, Frontiers in Psychiatry 12, 739985.

Engzell, P, A Frey and M D Verhagen (2021), “Learning loss due to school closures during the COVID-19 pandemic”, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 118(17), e2022376118.

Goodman, J (2014), “Flaking out: student absences and snow days as disruptions of instructional time”, NBER Working Paper No. w20221.

Gore, J, L Fray, A Miller, J Harris and W Taggart (2021), “The impact of COVID-19 on student learning in New South Wales primary schools: an empirical study”, The Australian Educational Researcher 48, 605-637.

Hallin, A E, H Danielsson, T Nordström and L Fälth (2022), "No learning loss in Sweden during the pandemic evidence from primary school reading assessments", International Journal of Educational Research 114, 102011.

Halloran, C, R Jack, J C Okun and E Oster (2021), “Pandemic schooling mode and student test scores: evidence from U.S. states”, NBER Working Paper No. w29497.

Kuhfeld, M, J Soland, B Tarasawa, A Johnson, E Ruzek and J Liu (2020), “Projecting the potential impact of COVID-19 school closures on academic achievement”, Educational Researcher 49(8), 549-565.

Maldonado, J E and K De Witte (2022), “The effect of school closures on standardised student test outcomes”, British Educational Research Journal 48: 49-94.

Meyers, K and M A Thomasson (2021), “Can pandemics affect educational attainment? Evidence from the polio epidemic of 1916”, Cliometrica 15: 231-265.

Oikawa, M, R Tanaka, S Bessho, A Kawamura and H Noguchi (2022), “Do class closures affect students' achievements? Heterogeneous effects of students' socioeconomic backgrounds”, RIETI Discussion Paper (22-E), 042.

OECD – Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development (2021), “The state of school education: one year into the COVID pandemic”, OECD Library.

Sacerdote, B (2012), “When the saints go marching out: long-term outcomes for student evacuees from Hurricanes Katrina and Rita”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 4(1): 109-135.

Tomasik, M J, L A Helblin and U Moser (2021), “Educational gains of in-person vs. distance learning in primary and secondary schools: a natural experiment during the COVID-19 pandemic school closures in Switzerland”, International Journal of Psychology 56: 566-576.

UNESCO – United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (2021), COVID-19 impact on education.