Most proposed policies aimed at mitigating global climate change – such as carbon taxes and cap-and-trade programmes – reflect a trade-off between long-run benefits and short-term economic costs. As suggested by Nordhaus (2008), appropriate climate policy is usually “a question of balance”. But what if there are policies for which there is no trade-off between lowering carbon emissions and promoting economic growth? These policies could accomplish two desirable outcomes and may receive increased political support.

In recent work, we provide evidence that policies aimed at slowing population growth can both increase growth in income per capita and lower growth in carbon emissions (Casey and Galor 2016, 2017).1,2 In other words, population policies may not be subject to an undesirable trade-off that is central to more commonly discussed options. Our findings, therefore, suggest that population policies could play an important role in the mitigation of global climate change.

Findings

Decreases in population growth impact the growth of carbon emissions through three interconnected effects:

- decreases in population tend to increase income per capita;

- increases in income per capita tend to increase carbon emissions (e.g. Raupach et al. 2007); and

- decreases in population, holding income per capita constant, tend to directly decrease carbon emissions (e.g. Raupach et al. 2007).

The net effect of a reduction in population growth on the growth in carbon emissions, therefore, depends on the relative size of two competing forces that it triggers: the direct reduction in carbon emissions, and the increase in carbon emissions caused by increases in income per capita.

In the first part of our analysis, we investigate cross-country data on income, population, and carbon emissions and find that increases in population have much greater effects on total carbon emissions than increases in income per capita. In other words, a region with 10,000 people and an income of $5,000 per capita emits significantly more carbon than a region with 5,000 people and an income of $10,000 per capita. Thus, even if decreases in population growth lead to large increases in the growth of income per capita, it will still be possible for carbon emissions to be significantly reduced.3

In the second part of our analysis, we focus on the example of Nigeria to demonstrate that it is indeed possible for population policies to both lower the growth of carbon emissions and increase the growth of income per capita. We use a recently constructed economic-demographic model to estimate the effect of lower population growth on economic outcomes (Ashraf et al. 2013). We then combine the results of the model with the estimates from the first part of our analysis to determine the overall effect of changes in population on carbon emissions. In particular, we examine the effect of an exogenous decrease in population growth – as given by the difference between the medium and low variants of the UN fertility projections – on the growth of carbon emissions and income per capita.

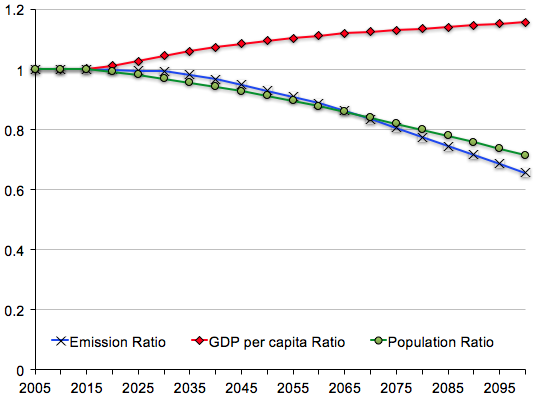

Figure 1. The effects of reduced population growth on carbon emissions and income per capita

Notes: The figure demonstrates that reductions in population growth from the medium fertility to the low fertility scenario (predicted for the period 2020-2100) lower carbon emissions and increase income per capita. All variables are measured as the ratio of the outcome under the low fertility scenario relative to the outcome under the medium fertility scenario. The model abstracts from any negative economic consequences of climate change.

The results are depicted in Figure 1. By 2050, emissions are 10% lower and income per capita is 10% higher in the low fertility scenario. By 2100, emissions are approximately 35% lower, while income is approximately 15% higher. Thus, we find that slower population growth has the potential to both increase the growth of income per capita and slow the growth of carbon emissions, even without accounting for the potential long-run economic benefits of reductions in carbon emissions.

Policy considerations

There are several policies that could lower population growth, leading to increases in the growth of income per capita and decreases in the growth of carbon emissions. Polices that promote gender equality, increase the return to human capital, or expand the availability of contraceptives, for example, all have the potential to lower fertility. Of particular interest are policies that increase the return to education, inducing parents to shift resources away from having more children and towards investing in the human capital of children. Research in economic growth demonstrates that these forces have played a substantial role in shaping long-run economic and demographic outcomes (Galor 2011, 2012).

Population-based policies may also garner greater political support than more conventional policy options. By eliminating the trade-off between long-run benefits and short-run economic costs, these policies may be able to overcome free-rider effects, which often complicate solutions to environmental problems that are global or international in nature (Stavins 2011). Similarly, the principle of common but differentiated responsibility points to the need for policy options that can mitigate climate change without inhibiting economic growth in poor countries (Bretschger 2015). Given the relatively high population growth rates in many developing economies, population policies may be able to help achieve this difficult goal, resulting in increased support in the international community.

Conclusion

Most policies aimed at mitigating global climate change face a trade-off between short-run economic outcomes and long-run changes in global temperature. By contrast, our recent work provides evidence that population policies may have the ability to both increase growth in income per capita and lower growth in carbon emissions. These policies could play an important role in the portfolio of actions aimed at mitigating climate change.

References

Ashraf, Q H, D N Weil and J Wilde (2013) "The effect of fertility reduction on economic growth", Population and Development Review, 39(1): 97-130.

Bretschger, L (2015) “Climate policy: Prices versus equity," VoxEU.org, 11 October.

Casey, G and O Galor (2016) “Population growth and carbon emissions”, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 11659.

Casey, G and O Galor (2017) "Is faster economic growth compatible with reductions in carbon emissions? The role of diminished population growth", Environmental Research Letters, 12(1): 014003.

Galor, O (2011) Unified growth theory, Princeton University Press.

Galor, O (2012) "The demographic transition: Causes and consequences", Cliometrica, 6(1): 1-28.

Nordhaus, W D (2014) A question of balance: Weighing the options on global warming policies, Yale University Press.

Raupach, M R, G Marland, P Ciais, C Le Quéré, J G Canadell, G Klepper and C B Field (2007) "Global and regional drivers of accelerating CO2 emissions", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104(24): 10288-10293.

Stavins, R N (2011) "The problem of the commons: Still unsettled after 100 years", American Economic Review, 101(1): 81-108.

Endnotes

[1] We are interested in population policies that affect population growth via voluntary decisions.

[2] Importantly, we discuss the potential for population policies to improve economic and environmental outcomes even without considering any long-run economic benefits from mitigating climatic change. It is in this sense that population policies alleviate the trade-off central to most proposed climate change policies.

[3] The influential DICE/RICE model, in contrast, assumes that carbon emissions are generated by total output without regard to the division between population and output per capita (Nordhaus 2008).