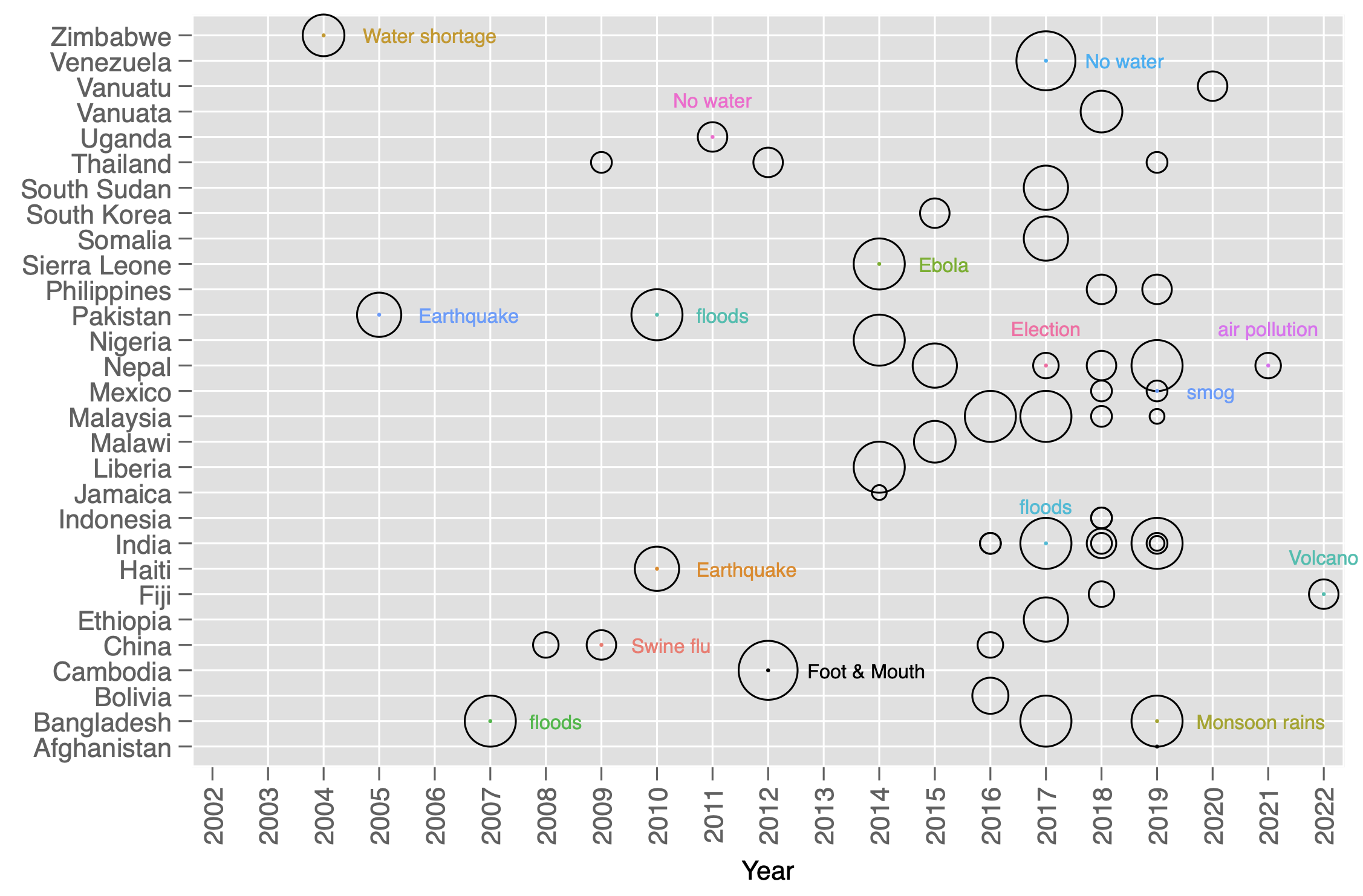

Education systems need to withstand frequent shocks, including conflict, disease, natural disasters, and climate events, all of which routinely close schools. COVID-19 led to historically long school closures, during which children in many low-income countries lost 1.7 years of schooling on average (Sabarwal et al. 2022). Other emergencies frequently close schools, such as Swine Flu in China in 2009, Foot and Mouth in Cambodia in 2012, and Ebola in 2014 in Sierra Leone. Schools also increasingly close because of air pollution, water shortages, and conflict. For example, between 2015 and 2019 alone more than 11,000 attacks on schools were documented in at least 93 countries (GCPEA 2020). Extreme climate events also take a toll. Monsoon rains and flooding in Bangladesh, India, Nepal, and Pakistan between 2017 and 2023 closed 50,000 schools. As climate change-related shocks increase, school closures will only become more frequent. The UN estimates that currently, around 222 million children around the world experience significant education disruptions due to emergencies. Figure 1 shows an index of the length of school closures and number of people affected by shocks that have disrupted schooling by country and year, and shows that these crises occur frequently and in many countries. Students, especially poor students, pay dearly for these school closures (Zillibotti et al. 2022). Yet in spite of the scale of these issues, there is limited evidence on how to make student learning resilient to frequent disruptions.

Figure 1 Documenting a set of education in emergencies, 2002-2022

Notes: This figure plots an index of the length of school closures and number of people affected by shocks that have disrupted schooling by country and year. The larger the bubble the larger either the length of school closure or the number of people affected, or both. More information on the database compilation is available in the paper. Data sources used by Angrist et al. (2023a): Compiled school closure information based on press releases of the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) ReliefWeb, World Vision, UNICEF, the BBC, and other local outlets.

Source: Angrist et al. (2023a)

New multi-country evidence on building more resilient education systems

In this column, we present results from a highly cost-effective programme tested across five countries during COVID school disruptions as well as an additional shock to education systems – a typhoon (Angrist et al. 2023a). We ran randomised control trials in Kenya, India, Nepal, Uganda and the Philippines to test a one-on-one weekly phone tutoring programme. Through 20-minute weekly phone calls, government teachers and NGO tutors delivered targeted instruction to primary school students (grades 3 to 5) on foundational numeracy skills including addition, subtraction, multiplication and division. Students and their caregivers also received weekly math problems delivered via text message. This approach draws on some of the most cost-effective, proven principles for increasing learning such as targeting instruction to the child’s level of knowledge (Banerjee et al. 2017, Glennerster 2023) and tutoring (Nickow et al. 2020).

The programme was first tested in Botswana in 2020 during COVID and found to be highly cost-effective (Angrist et al. 2022). When COVID closed schools, the Botswana-based NGO, Youth Impact, which had been supporting evidence-based education interventions in public schools, developed this programme to support remote learning. After promising results from the 2020 RCT in Botswana, a coalition of NGOs, governments, multi-laterals, and researchers in five other countries (India, Kenya, Nepal, Philippines, and Uganda) were keen to test and adapt the phone tutoring programming in their context. We randomly assigned students in these five countries into various groups: a treatment group that received weekly SMSs with maths problems; a treatment group that received the weekly SMSs plus a weekly 20-minute tutoring call with targeted instruction; or a control group. In total, nearly 17,000 students were part of the study. The trials took place between 2020 and 2022, and represent some of the most rapid and comprehensive multi-country evidence ever generated on an education intervention.

The programme was effective across five countries with large, consistent impacts on learning

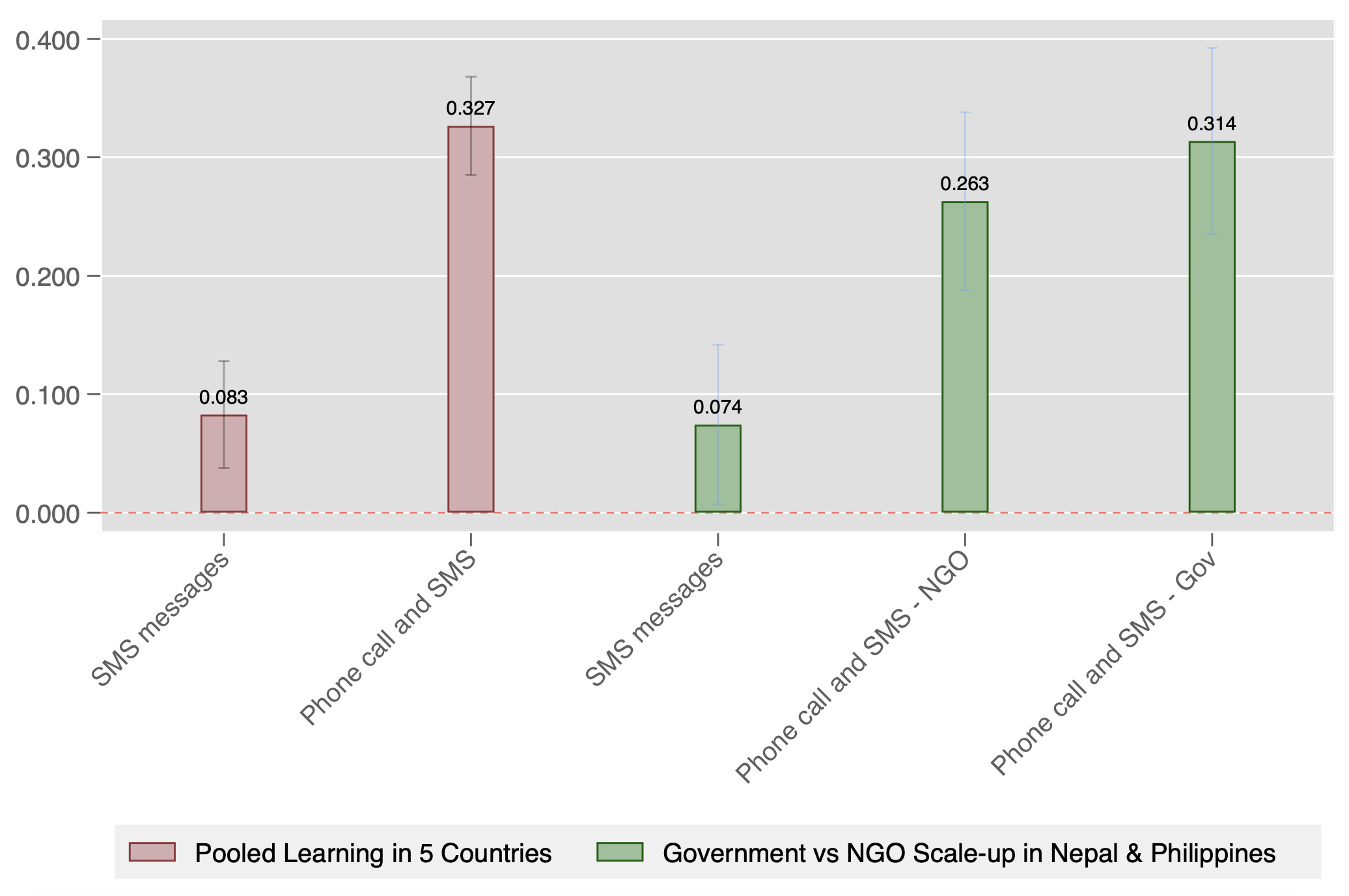

We found consistently large and robust impacts of phone call tutorials on student learning across contexts. On average, phone calls improved learning by 0.327 standard deviations, over a third larger than the median effectiveness of education interventions (Evans and Yuan 2022). Results are shown graphically in Figure 2. While children who received phone tutoring learned more in every location, the greatest gains were in the Philippines and Uganda (0.45 and 0.89 standard deviations, respectively), where school closures were longest.

These results translate into meaningful learning gains. In Uganda, for example, less than 20% of grade 4 students could divide at baseline, but by endline, nearly 50% of students in the treatment group can. On average, across all countries, we find a 65% increase in the share of students who learn division. The effects are largest for students whose caregivers have only a primary education (rather than secondary and beyond), suggesting that results are strongest when there are fewer alternative educational support systems at home.

While the phone calls were effective across contexts, the weekly SMSs alone were more mixed. For students in this group, learning improved only in the Philippines and Uganda. While very cheap, such a light SMS-only approach may not be sufficient to reliably boost learning in emergencies. These results suggest that SMS messages can work in contexts with the largest need, but that live phone call instruction might be necessary to strike the balance of being intensive enough to deliver impact that can be sustained and scaled across diverse contexts while remaining cheap and scalable.

Figure 2 Learning outcomes (standard deviations) at scale across five countries and scaled by governments

Note: This figure shows the impacts of the programme in Standard Deviations. Red bars show impacts of the two treatment arms pooled across all five countries, and the green bars showing results for the two countries with government and NGO implementers.

- Effective when delivered by government teachers and NGO instructors

We find the programme is effective across different implementation models. In both the Philippines and Nepal, we randomised whether the intervention was provided by NGO instructors or government teachers. Both were equally effective at improving learning, suggesting both that the programme is robust to different implementation approaches and has potential to scale within government systems.

- Effective on non-cognitive skills and wellbeing

We also find positive effects on non-cognitive skills, with a 29% increase in children’s ambition, for example. We further find positive effects on measures of well-being, such as enjoying school and worrying less. Our results provide evidence that educational interventions such as phone call tutorials can promote both cognitive as well as non-cognitive skills, both of which are important for future life outcomes (Jackson 2018).

- Effective in another education emergency: Typhoon Rai

Beyond the COVID school disruptions, an additional education emergency took place during the trial. A devastating typhoon in the Philippines destroyed 4,000 classrooms and disrupted learning for 2 million children (UN OCHA 2022). The interaction between the areas affected by the typhoon and randomisation to phone call tutorials and SMS messages produced a quasi-experiment. The results show that despite this, phone call tutorials continued to be effective, with 0.26 standard deviation gains relative to the control group. These results demonstrate that phone call tutorials can be effective across multiple types of education emergencies.

- Targeted instruction was a key component of effectiveness

What explains the striking effectiveness of the approach across such diverse contexts? There are a few leading explanations. One likely explanation is that the underlying mechanisms of the programme rely on proven best practices in education. For example, tutoring has been shown to be one of the most effective, though expensive, approaches to improving learning in high-income settings (e.g. Nickow et al. 2020). The phone call tutorials in our study provide a cheap and scalable version of tutoring applicable in low- and middle-income contexts. Further, since the phone calls include frequent light-touch learning assessments, they enabled highly targeted instruction to each child’s learning level, another approach shown to consistently improve learning (e.g. Banerjee et al. 2017, Muralidharan et al. 2019, Duflo et al. 2022).

Consistent with this, we found that learning effects were greatest in the countries that had the most targeted instruction. In a companion paper (Angrist et al. 2023b), we use the weekly light-touch learning assessments collected as part of monitoring data to document increasing targeting accuracy of the programme trial-by-trial. For example a session was considered ‘accurately targeted’ if a student had passed the addition learning assessment one week and was taught subtraction the following week, or if they’d failed addition and were re-taught addition the subsequent week. In countries where instruction was most accurately targeted, effect sizes were also greatest. For example, in Nepal, where instruction was targeted 51% of the time, learning effect sizes were 0.14 standard deviations; in Uganda, where instruction was targeted 82% of the time, effect sizes were 0.89 standard deviations. This suggests that targeting instruction is likely a key mechanism for the programme’s success. Additional evidence in support of the importance of targeting comes from other studies of phone-based programmes that did not incorporate targeted instruction and in turn did not have an impact (e.g. Crawfurd et al. 2023).

Conclusion

Given the frequency and cost of emergencies that disrupt schooling, education systems need resilient solutions that can be deployed quickly, reach many households, are low cost, and can be effective across multiple contexts and delivery models. Our results show that a phone tutoring programme can be highly effective across contexts, emergency types, and implementer profiles, including both government and NGO delivery, pointing to its potential scalability. Further, the programme is highly cost-effective. Average costs per student for the duration of the programme (less than three hours of instruction) averaged $12. The programme yields 3.4 high-quality years of schooling gained per $100, ranking in the top ten out of 150 education interventions reviewed (Angrist et al. 2020). Our results suggest phone-based targeted tutoring programmes can deliver cost-effective learning gains across contexts and with governments, and can be deployed to build more resilient education systems.

Editors' note: This column is published in collaboration with VoxDev.

References

Angrist, N, D K Evans, D Filmer, R Glennerster, F H Rogers, and S Sabarwal (2020), “How to improve education outcomes most efficiently? A comparison of 150 interventions using the new Learning-Adjusted Years of Schooling metric”.

Angrist, N, P Bergman, and M Matsheng (2022), “Experimental evidence on learning using low-tech when school is out”, Nature Human Behaviour, 1-10.

Angrist, N, M Ainomugisha, S P Bathena, P Bergman, C Crossley, C Cullen, T Letsomo, M Matsheng, R M Panti, S Sabarwal, and T Sullivan (2023a), "Building Resilient Education Systems: Evidence from Large-Scale Randomized Trials in Five Countries”, NBER Working Paper No. 31208.

Angrist, N, C Cullen, M Ainomugisha, S P Bathena, P Bergman, C Crossley, T Letsomo, M Matsheng, R M Panti, S Sabarwal, and T Sullivan (2023b), "Learning Curve: Progress in the Replication Crisis", AEA Papers and Proceedings 113: 482-488.

Banerjee, A V, S Cole, E Duflo, and L Linden (2007), “Remedying education: Evidence from two randomized experiments in India”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 122(3): 1235-1264.

Crawfurd, L, D K Evans, S Hares, and J Sandefur (2023), “Live tutoring calls did not improve learning during the COVID-19 pandemic in Sierra Leone”, Journal of Development Economics 164: 103114.

Duflo, A, J Kiessel, and A Lucas (2020), "External Validity: Four Models of Improving Student Achievement”, NBER Working Paper No. 27298.

GCPEA (2020), “Education Under Attack 2020, Widespread Attacks on Education More than 11,000 attacks in Past 5 Years”.

Glennerster, R (2023), “Policies to improve global learning”, VoxDev.org, 7 May.

Evans, D K, and F Yuan (2022), “How big are effect sizes in international education studies?”, Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 44(3): 532-540.

Hanushek, E, L Woessmann, and S Gust (2022, December 5), “A world unprepared: Missing skills for development”, VoxEU.org. 5 December.

Jackson, C K (2018), “What do test scores miss? The importance of teacher effects on non–test score outcomes”, Journal of Political Economy 126(5): 2072-2107.

Nickow, A, P Oreopoulos, and V Quan (2020), “The impressive effects of tutoring on pre-k-12 learning: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the experimental evidence”.

Muralidharan, K, A Singh, and A J Ganimian (2019), “Disrupting education? Experimental evidence on technology-aided instruction in India”, American Economic Review 109(4): 1426-60.

Sabarwal, S, A Yi Chang, N Angrist, and R D’Souza (2022), "Learning Losses and Dropouts: The Heavy Cost COVID-19 Imposed on School-Age Children", in Collapse and Recovery - How the COVID-19 Pandemic Eroded Human Capital and What to Do about It, World Bank Group.

UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (2022), “Philippines: Super Typhoon Rai (Odette) Humanitarian Needs and Priorities”, 2 February.

Zilibotti, F, M Doepke, G Sorrenti, and F Agostinelli (2022), “The triple impact of school closures on educational inequality”, VoxEU.org. 21 January.