Mental health conditions have worsened in many countries in recent decades. Globally, one in every eight individuals lived with a mental health disorder in 2019 (IHME 2019), and it is estimated that 12 billion working days are lost globally every year due to anxiety and depression (WHO 2022). In the US, 22.8% of the adult population reported having any mental illness in 2021 (up from 18.1% in 2014) and 5.5% reported a serious mental illness (up from 4.1% in 2014). However, access to treatment remains limited, potentially due to stigma (Bharadwaj et al. 2015).

Recent work has shown that a multitude of events can impact mental health conditions (Ridley et al. 2020). For instance, mental health deteriorates during an economic crisis, as a result of job loss, as well as individuals gain access to social media (Braghieri et al. 2022, Golberstein et al. 2019, Paul and Moser, 2009). The mental health effects of negative shocks can also be long-lasting. Research has shown that adults’ mental health is affected by the in-utero exposure to negative shocks as well as by the experience of intense bombing during the initial years of life (Persson and Rossin-Slater 2018, Akbulut-Yuksel et al. 2022).

We study a largely overlooked channel, notably whether the provision of income support through social security can improve mental health by alleviating financial constraints. More in details, we ask whether receiving a more generous unconditional cash transfer reduces the number of bad mental health days among programme recipients.

This is a highly replicable intervention in place in various forms in different countries, but debates on its trade-offs constrains wider adoption, especially in higher-income countries. In a recent paper, we provide some of the most comprehensive evidence to date on the mental health effects of the receipt of unconditional cash transfers in the US (Pignatti and Parolin 2023).

Our study context is the 2021 temporary expansion of the Child Tax Credit (CTC). The CTC is the largest tax credit in the US and it targets families with children. Before 2021, however, households with no reported earnings were not eligible for the benefit. Additionally, benefit levels increased with income, up to a cap. As a result, it is estimated that one out of three US children did not receive the full amount. The 2021 reform, instead, made CTC eligibility unconditional on earnings, increased benefit levels (especially for low-income households) and modified the system of benefit receipt (i.e. from lump-sum payments at the moment of tax filling to monthly transfers). It is estimated that the CTC expansion greatly contributed to reducing child poverty in the US during the COVID-19 pandemic.

However, the changes introduced in 2021 were not extended at the end of the year, and the CTC returned to its pre-reform system starting in 2022.

Our research design exploits differences in benefit levels for households with children of different age. The maximum benefit level was equal to $2,000 for children of all ages before 2021. The reform raised this cap to $3,000 for families with children aged 6 to 17, and $3,600 for families with children below the age of 6. We leverage this differential change in benefit levels in difference-in-differences setting, using rich survey data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), a nationally representative survey that has been administered in the US since 1984 and is the largest health-related survey worldwide.

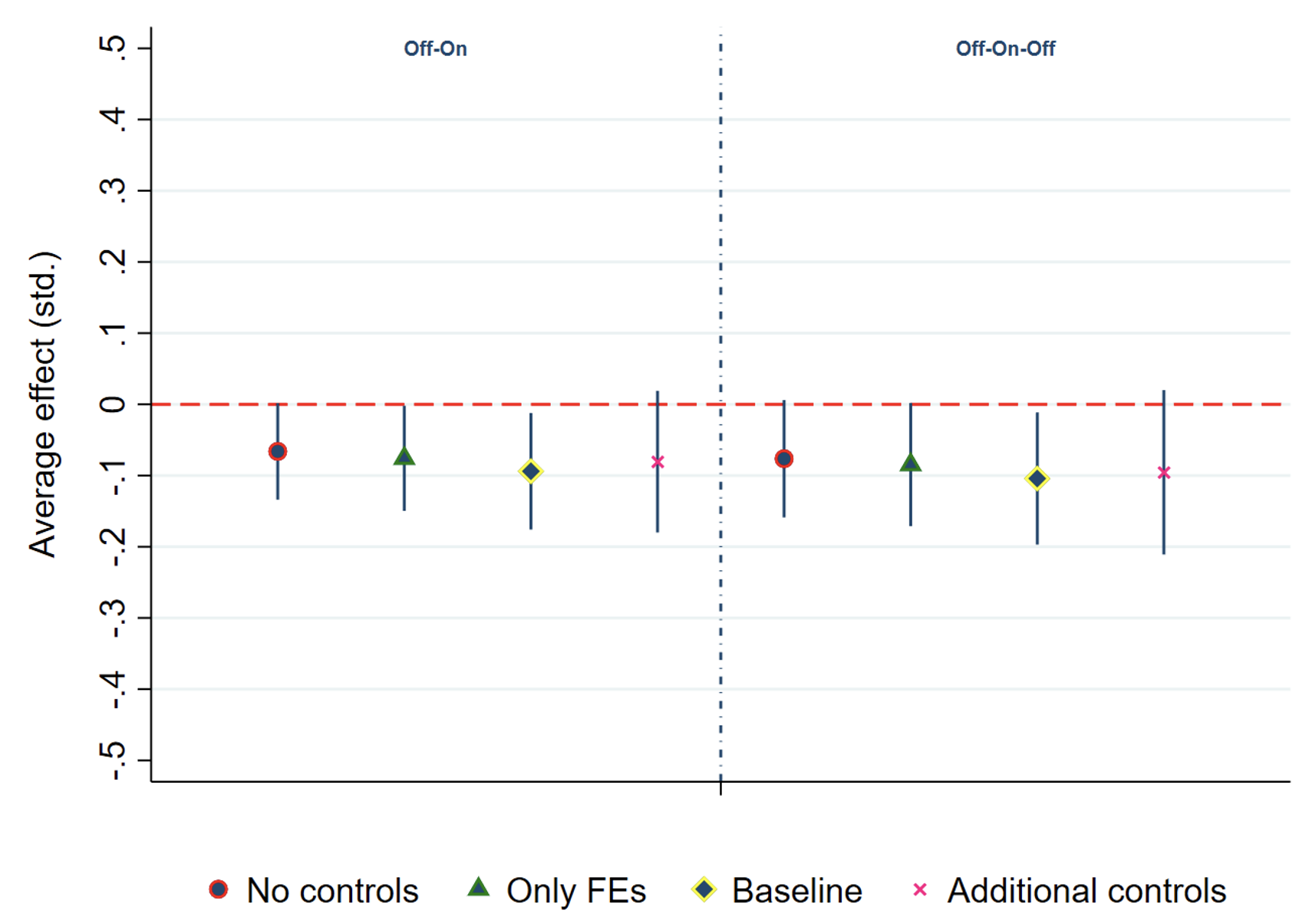

Our results indicate that the receipt of a more generous CTC reduced the number of self-reported bad mental health days (Figure 1). In our preferred specification, the more generous benefit decreases the number of mental health days in the previous month by 0.094 standard deviations. This is similar in size to the negative impact on mental health from the diffusion of Facebook in US colleges (Braghieri et al. 2022), and around 25% of the negative impact of job loss on mental health (Paul and Moser 2009). The positive effects on mental health materialise a few months after the first monthly transfer, but disappear as soon as the benefit is withdrawn in late 2021. The effect materialises along the intensive margin, by decreasing the number of bad mental health days among individuals reporting at least one bad mental health day in the previous month.

Figure 1 Effects of a more generous benefit on the self-reported number of bad mental health days

Notes: The figure reports point estimates and 90% confidence intervals for treatment effects on mental health, where the treated group consists of families with children aged 0-5 and the control group includes families with children aged 6 and above. The outcome of interest is normalized to have mean of zero and standard deviation of one in the pre-treatment period. We report results using two different definitions of the post-treatment period (“Off-On” and “Off-On-Off”, where the post-treatment period ends in December 2021 or February 2022, respectively). We additionally present different specifications that vary according to the types of covariates included in the analysis, from no controls (circle with red outline) to only time and state fixed effects (triangle with green outline), including also individual characteristics for age, number of children and marital status (diamond with yellow outline) and including additional controls for race, ethnicity, educational attainments and income brackets (pink cross).

We test whether the positive effects on mental health are driven by changes in labour market status, health insurance coverage or health care use. However, we find very small and generally insignificant treatment effects on all these dimensions. Instead, the positive effects of CTC receipt on mental health are likely driven by greater consumption (Parolin et al. 2022).

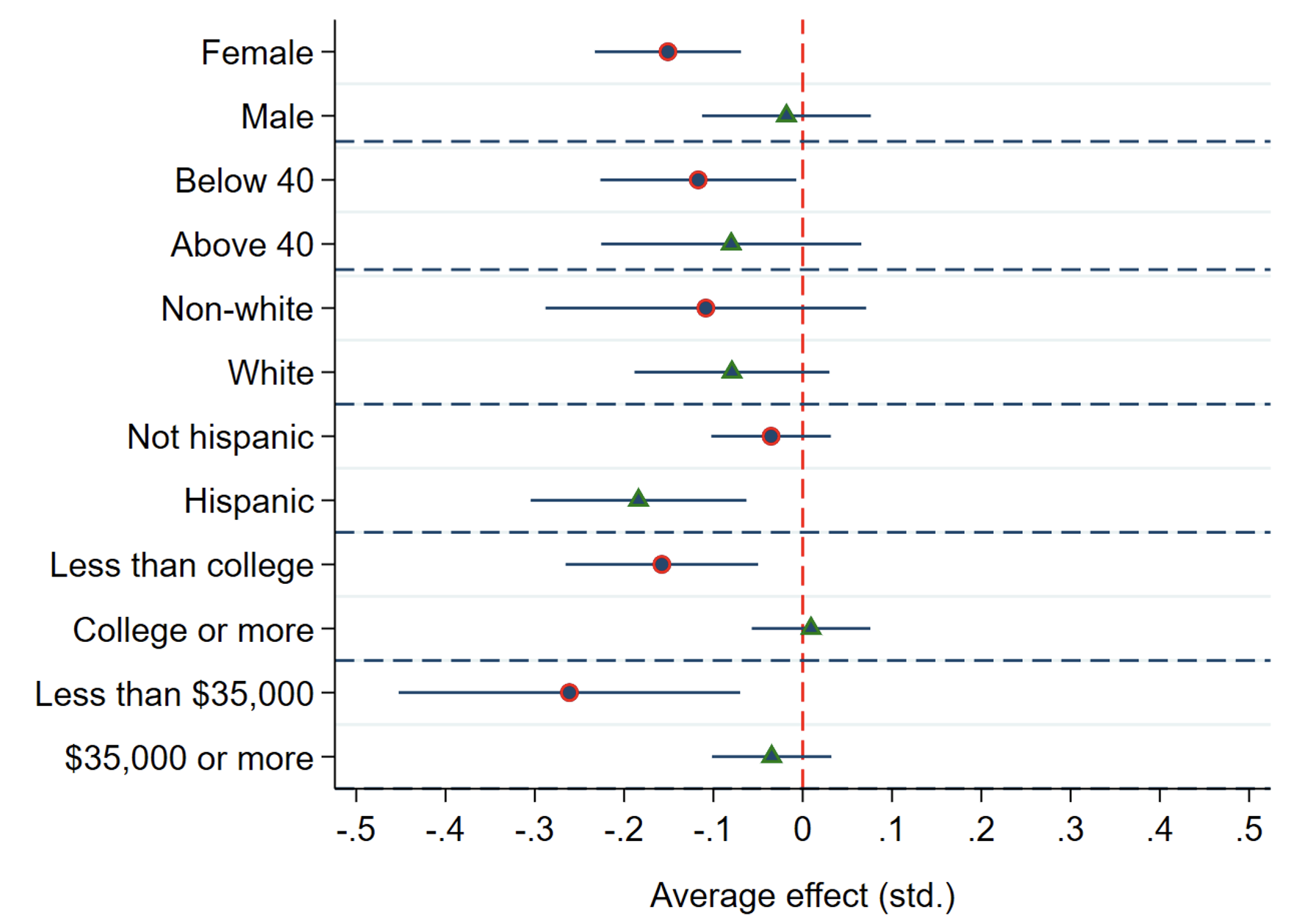

This is also consistent with the results that emerge from our heterogeneous analysis (Figure 2). In particular, we find that treatment effects on mental health are stronger for women, young adults (below the age of 40), low-educated individuals (with less than college degree), and people in low-income households (total household income below $35,000).

We document that these groups traditionally report higher rates of mental health distress. Additionally, these groups are on average more likely to be financially constrained, and might therefore benefit relatively more from the receipt of a more generous transfer.

Figure 2 Heterogeneous effects on the number of bad mental health days, by individual or household characteristics

Notes: The figure reports point estimates and 90% confidence intervals for treatment effects on mental health, where the treated group consists of families with children aged 0-5 and the control group includes families with children aged 6 and above. The outcome of interest is normalized to have mean of zero and standard deviation of one in the pre-treatment period. We report results only for the “Off-On” definition of the post-treatment period (see note to Figure 1 for details) and including controls corresponding to those in the “Baseline” specification (see note to Figure 1 for details).

Though mental health concerns are high and rising in many wealthy countries, our study demonstrates that cash support, at least for families with children, could be one strategy for reducing the number of bad mental health days in a given month.

References

Akbulut-Yuksel, M, E Tekin and B Turan (2022), “Wartime children and long-term mental health”, VoxEU.org, 18 October.

Bharadwaj, P, M M Pai and A Suziedelyte (2015), "Mental health stigma," VoxEU.org, 3 July.

Braghieri, L, R Levy, and A Makarin (2022), “Social media and mental health”, VoxEU.org, 22 July

Golberstein, E, G Gonzales, and E Meara (2019), “How Do Economic Downturns Affect the Mental Health of Children? Evidence from the National Health Interview Survey”, Health Economics 28(8): 955–70.

IHME – Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (2019), Global health data exchange, technical report.

Paul, K I and K Moser (2009), “Unemployment Impairs Mental Health: Meta-Analyses”, Journal of Vocational Behavior 74(3): 264–82.

Persson, P and M Rossin-Slater (2018), “Family Ruptures, Stress, and the Mental Health of the Next Generation”, American Economic Review 108(4-5): 1214–52.

Parolin, Z, G Giupponi, E Lee, and S. Collyer (2022) “Consumption Responses to an Unconditional Child Allowance in the United States”, OSF Preprints, Center for Open Science.

Pignatti, C and Z Parolin (2023), "The Effects of an Unconditional Cash Transfer on Mental Health in the United States," IZA Discussion Papers 16237.

Ridley, M, G Rao, F Schilbach, and V Patel. (2020), “Poverty, Depression, and Anxiety: Causal Evidence and Mechanisms”, Science 370(6522): 1289–1289.

WHO (2022), World mental health report: Transforming mental health for all, Technical report.