In recent years, the electoral fortunes of authoritarian populism have spurred a policy-relevant debate regarding the breeding ground of the political support for authoritarian parties and leaders (Danieli et al. 2023, Rodrik 2019, Tabellini 2019). Various key determinants behind this rise have been identified: long-term economic decay, rural depopulation, regional inequalities, the Great Recession, globalisation, immigration, and cultural backlash against progressive values. It is commonly acknowledged that all these factors have contributed to a growing dissatisfaction with mainstream parties, blamed for failing to face these new challenges. This, in turn, sparked the ‘revenge of the places that don’t matter’ (Rodriguez-Pose 2018). But what about the ‘places that don’t recover’?

A tale of two earthquakes

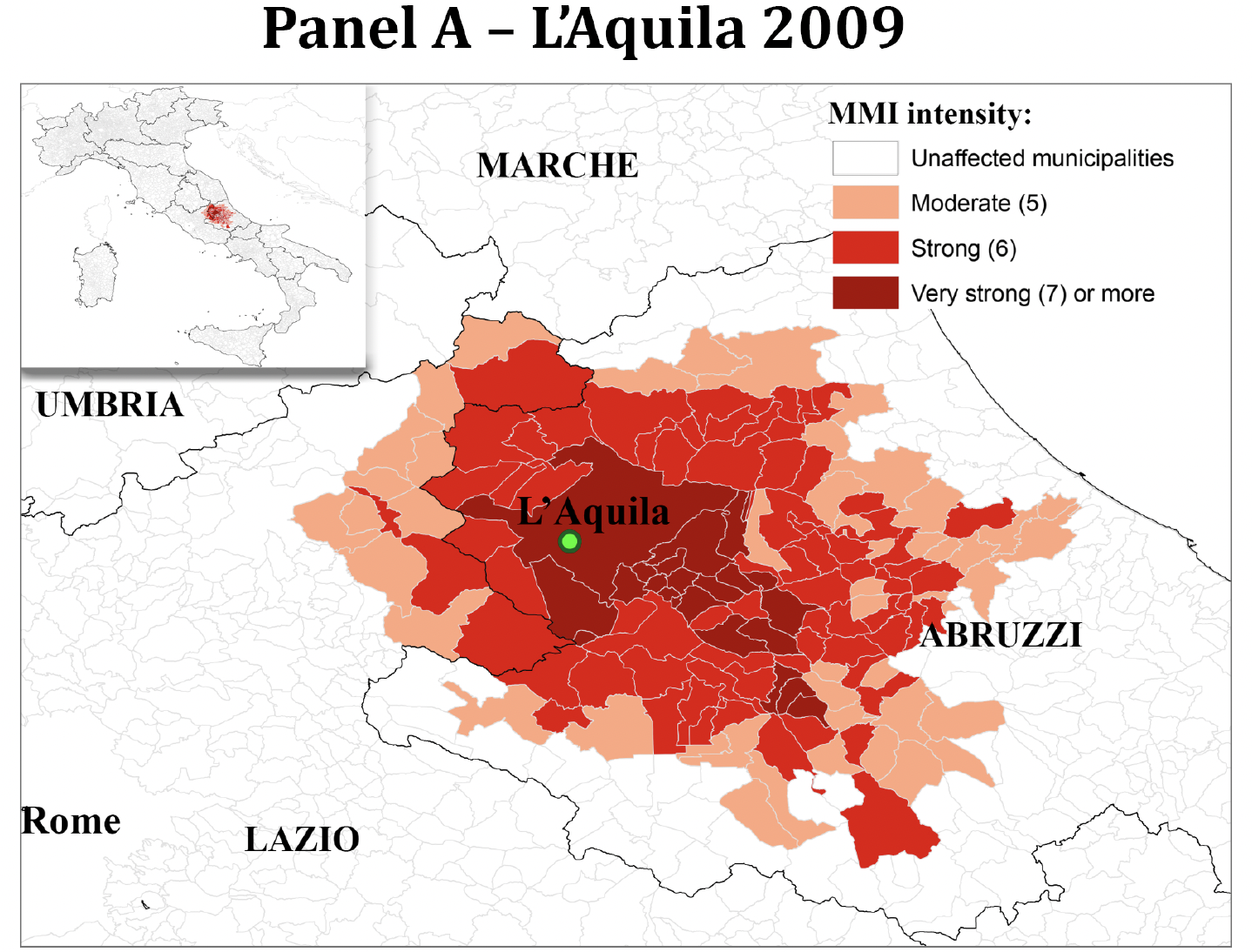

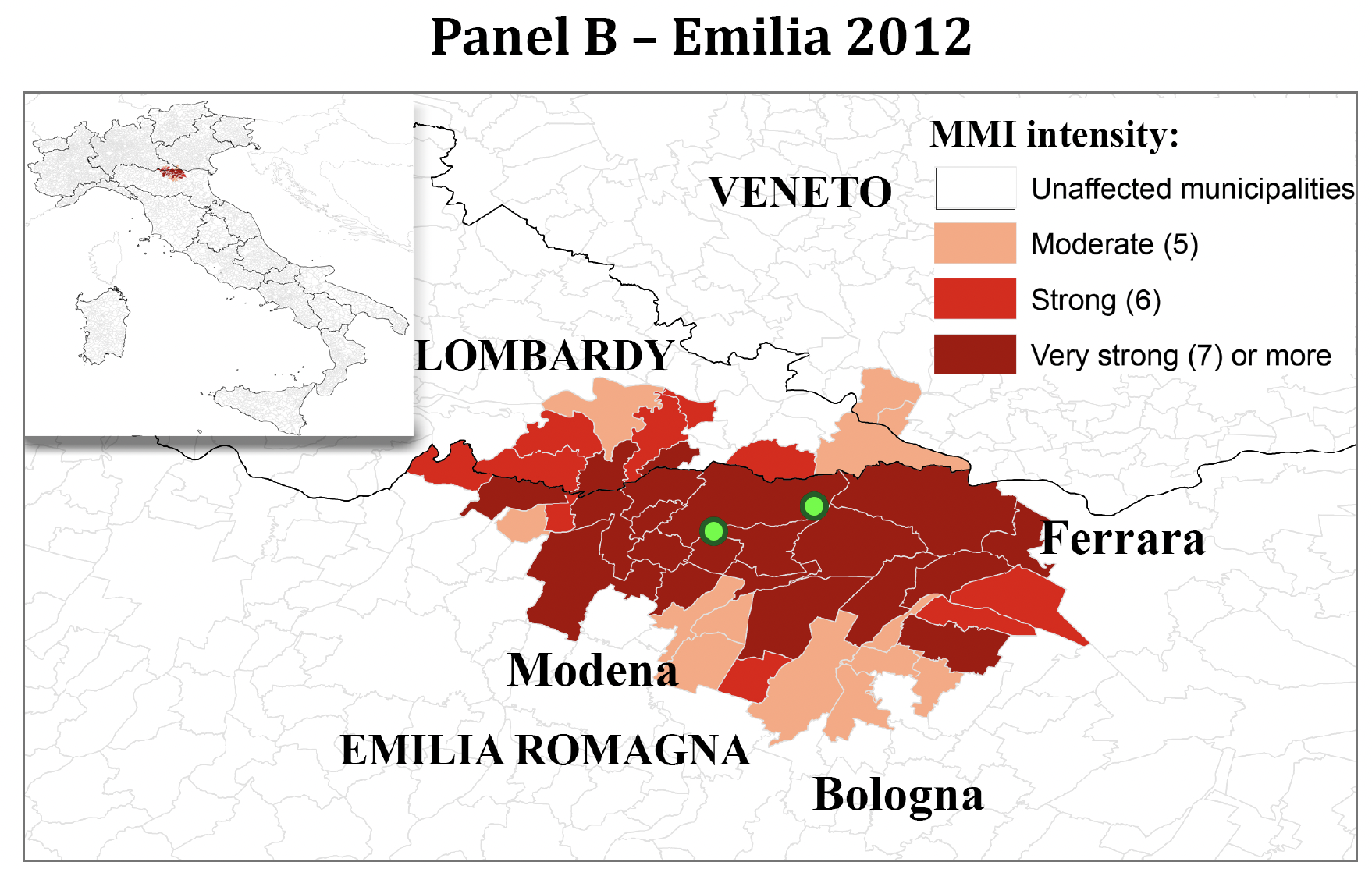

While acknowledging the relevance of long-term trends and global transformations, in our recent work (Cerqua et al. 2023), we take another route and investigate the catalyst role of local shocks, such as natural disasters, in engendering citizens’ support for authoritarian parties. Our focus is on two major earthquakes that struck Italy in recent times: the 2009 L'Aquila and 2012 Emilia earthquakes (Figure 1). The two earthquakes had comparable magnitude and brought about substantial economic and physical damage and severe human losses.

Figure 1 Earthquake maps

The similarities, however, end here, as the two earthquakes were followed by strikingly different post-disaster management. The L’Aquila reconstruction process was centralised, with local and regional duties delegated to the national headquarters, and the post-disaster management was plagued by bureaucratic delays, corruption, and infiltration by organised crime (Alexander 2013). Moreover, the reconstruction process was strongly politicised by the then Italian Prime Minister, Silvio Berlusconi. Conversely, the Emilian reconstruction was facilitated by a model of local governance characterised by a balance between public and private action, which actively involved people in the rebuilding of their communities.

Did these differences also translate into changes in voting behaviour?

The electoral aftermath

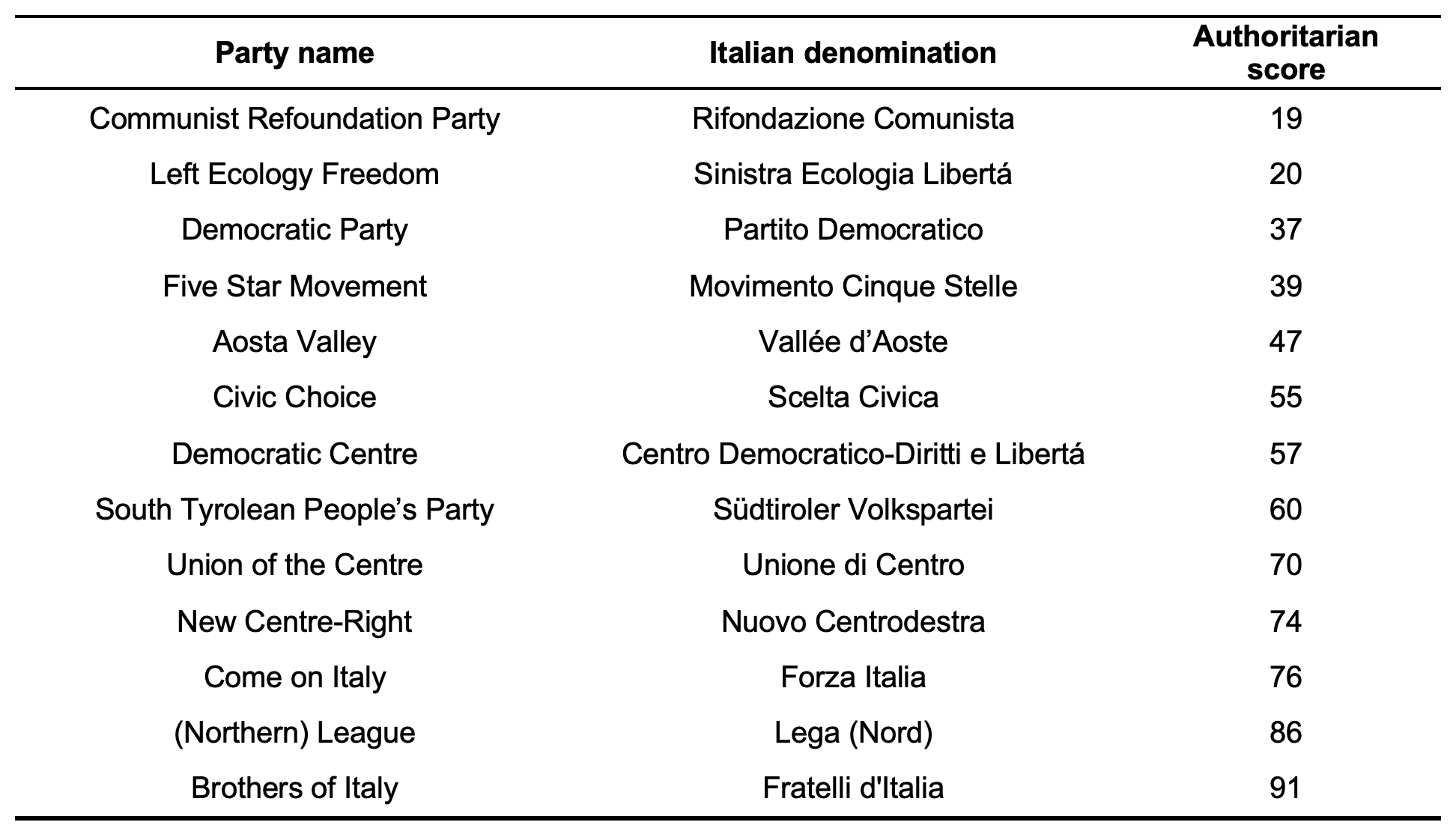

Through a rigorous identification strategy based on a quasi-experimental methodology (non-parametric matching difference-in-differences for time-series cross-sectional data) and a comparative natural experiment approach, we assess the electoral repercussions of the two earthquakes in the post-disaster electoral rounds for national and European elections. Our outcome variable is ‘authoritarian voting’ – a score calculated for each electoral round by multiplying the voting share of each party by their authoritarian scores reported in Table 1. These scores were built by Norris and Inglehart (2019) using the 2014 Chapel Hill expert survey, and capture the level of adherence of each party to a range of authoritarian values, such as support for anti-immigrant and nationalist foreign policies, law and order, traditional values, and opposition to more liberal lifestyles.

Table 1 Authoritarian scores for Italian parties

Source: Norris and Ingelhart (2019)

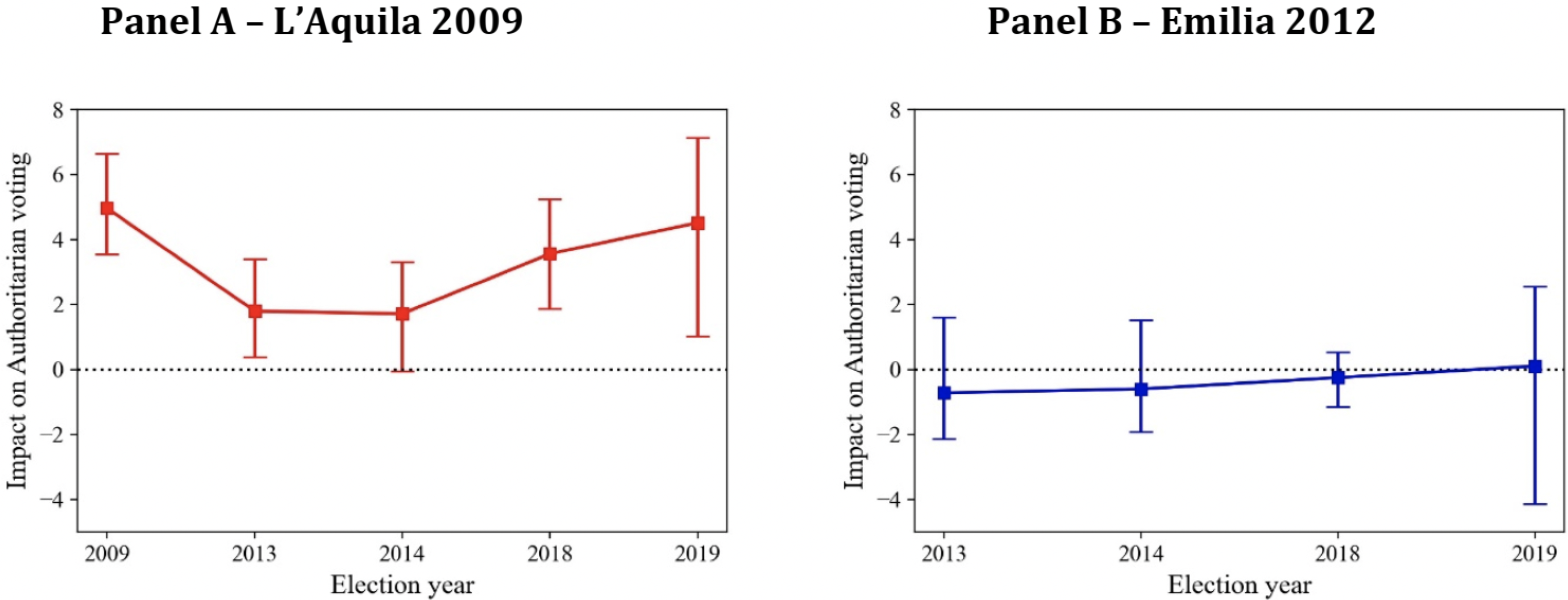

The key results of our paper are displayed in Figure 2 for L’Aquila 2009 (Panel A) and Emilia 2012 (Panel B), where we show the post-shock dynamic effects. The story that emerges from the figure is straightforward: despite the comparable physical magnitude, the two seismic events resulted in starkly contrasting electoral outcomes in the affected areas.

For L’Aquila 2009, we observe a sizable, statistically significant and long-lasting increase in voting for authoritarian right-wing parties. When we split the sample depending on intensity cut-offs, we see that the voting effects are more pronounced in the areas that experienced a stronger seismic intensity (up to an increase of 8 points in the authoritarian score). In contrast, the Emilian earthquake had no detectable impact on authoritarian voting: the estimates reveal that people living in the affected municipalities did not alter their voting behaviour as a reaction to the earthquake, regardless of the intensity experienced.

Figure 2 The impact of L’Aquila 2009 and Emilia2012 on authoritarian voting

Notes: In the three election rounds before the earthquake, the pre-treatment values of the dependent variable and other covariates were used in the matching step to generate a suitable control group for each affected municipality. In the paper, we show that the pre-treatment trajectories of all these variables were parallel between affected and non-affected municipalities, which constitutes indirect evidence for the validity of the parallel-trends assumption.

Reconstruction and trust

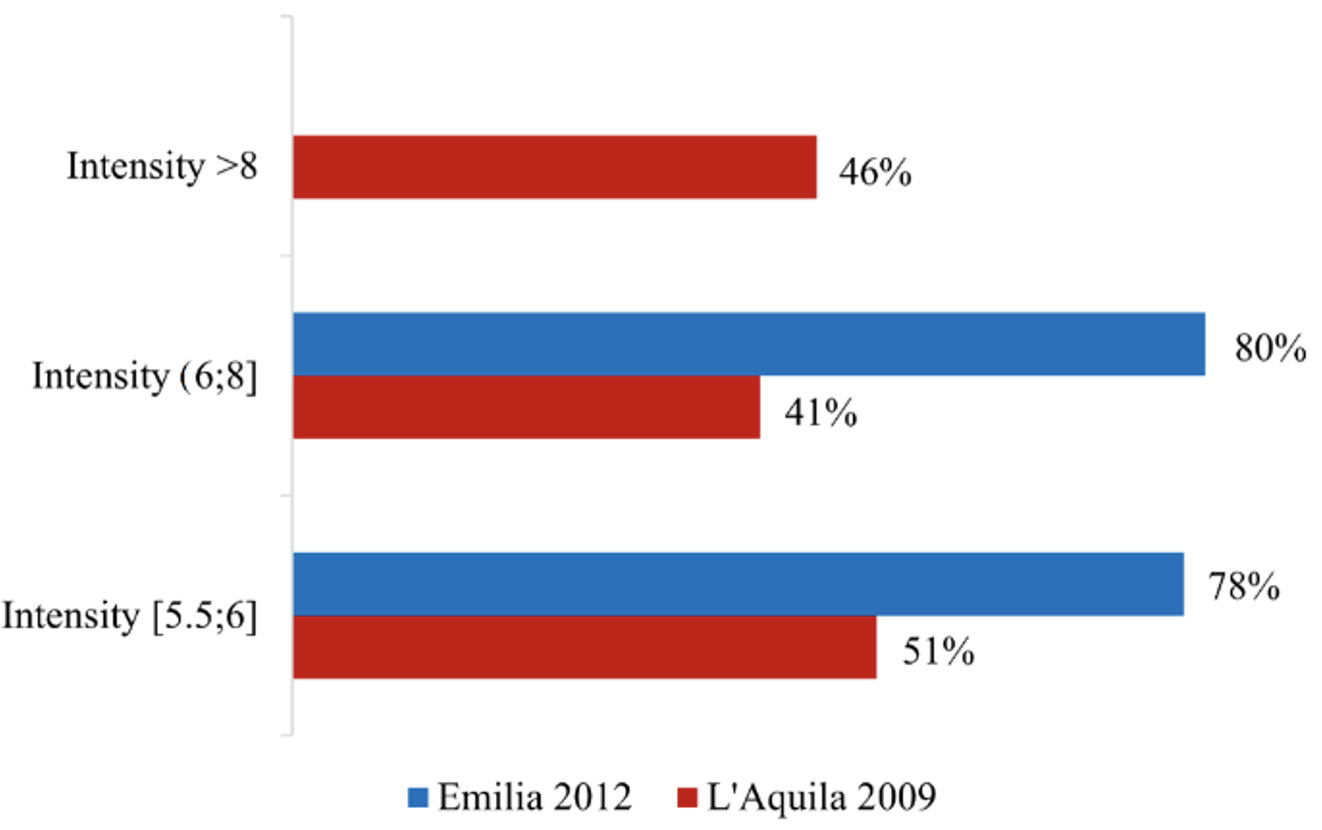

What are the drivers behind such heterogeneity? To frame our results, we have explored an array of potential mechanisms by taking into account economic, political, material, social, and institutional factors. In a nutshell, the contrasting electoral outcomes between the two earthquakes can be traced back to stark differences in the speed and management of post-disaster reconstruction process, with L'Aquila 2009 affected areas lagging far behind the more resilient Emilian territories. Figure 3 shows, for both earthquakes, the share of reconstruction fund disbursement completion (a proxy for the reconstruction progress) as of 2020. Despite occurring more than three years after the L'Aquila event, the Emilian earthquake has been followed by a much more rapid and smooth recovery, even when comparing only areas suffering similar levels of destruction.

Figure 3 Reconstruction progress as of 2020

Notes: The figure shows the amount of reconstruction funds allocated by the central government already disbursed by local institutions to implement the reconstruction projects in 2020 (expressed in percentage points). Authors’ elaboration on scraped data taken from special reconstruction centres and regional authorities.

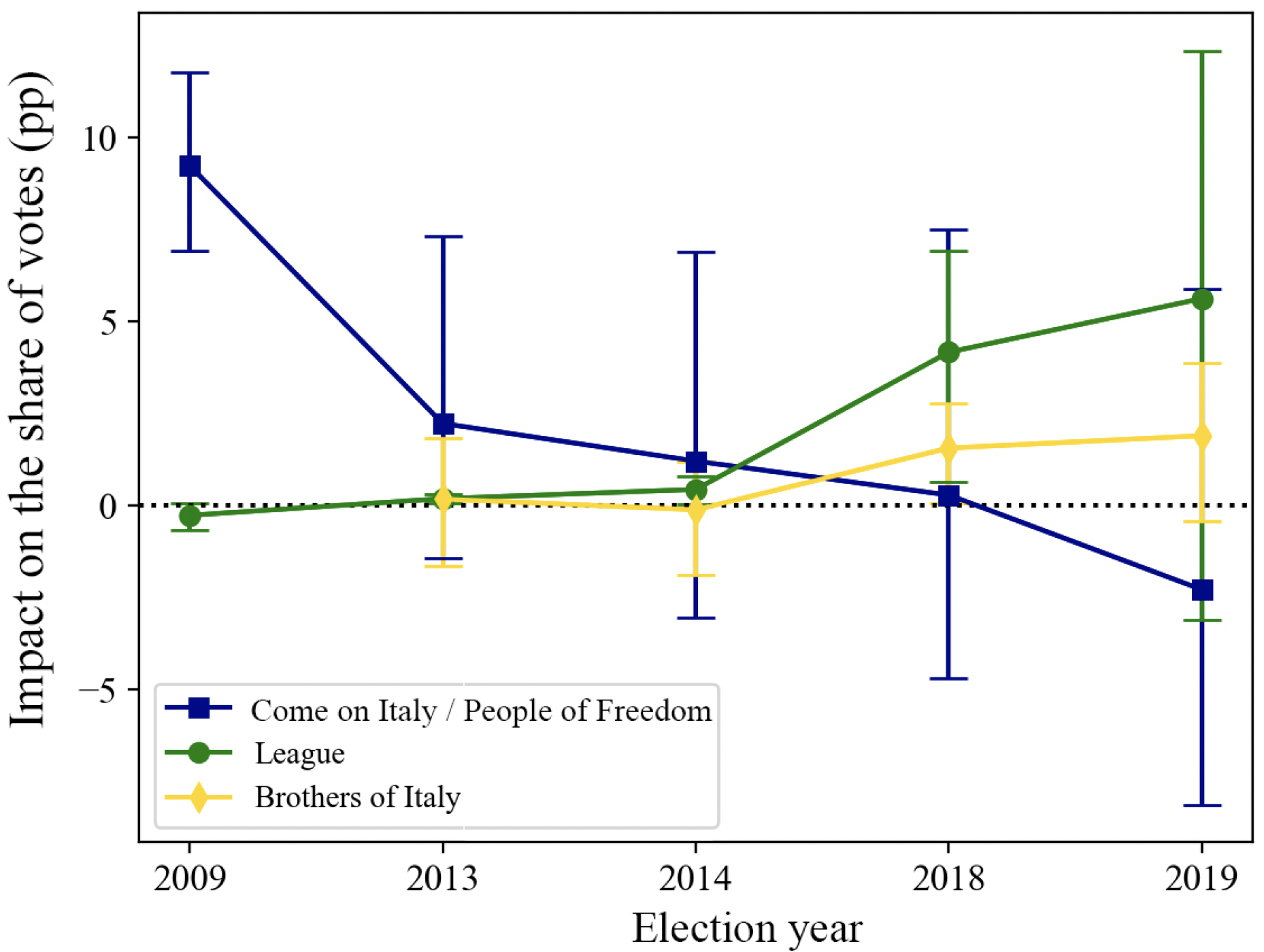

This, in turn, led to a decline in institutional trust – as proxied by the turnout at the European elections – in areas affected by the L’Aquila 2009 earthquake, which did not occur in the municipalities hit by the Emilian quake. Therefore, the post-Aquila 2009 stalemate brought about distrust in the disappointed communities who, after the initial belief in Berlusconi's electoral promises, started to shift their votes towards right-wing parties at the extreme of the authoritarian spectrum (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Impact of L’Aquila 2009 on the share of votes for Berlusconi’s party (Come on Italy/People of Freedom), League and Brothers of Italy

In sum, one area did not recover, the other did; the former reacted by voting for authoritarian right-wing parties, the latter did not.

Institutional failures alienate local communities

Leading scholars have stressed (Acemoglu and Robinson 2019) that disappointed people start to support radical alternatives when existing institutions lose their legitimacy or fail to cope with new challenges. Our findings provide empirical support for this hypothesis. The rise of authoritarian voting emerging after L'Aquila 2009 was shaped by the inability of institutions, despite initial pledges, to ensure a prompt recovery process. The impasse engendered distrust towards public institutions, feelings of abandonment and resentment and, ultimately, revenge through the ballot box. The failure to rebuild places translated into a failure to rebuild local communities, so those communities looked for someone else to address their unfulfilled claims. The policy lesson is clear: mismanaging shocks can have a high political cost and lead to social fragmentation and radical political views. Places that don't recover tend to embrace authoritarian attitudes: in times of pandemics, geopolitical tensions, and economic turmoil, this alarm bell should not go unnoticed.

Authors' note: The views expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the institution they belong to.

References

Acemoglu, D and J A Robinson (2019), “How Do Populists Win?”, Project Syndicate, 31 May.

Alexander, D (2013), “An evaluation of medium-term recovery processes after the 6 April 2009 earthquake in L'Aquila, Central Italy”, Environmental Hazards 12(1): 60-73.

Cerqua, A, C Ferrante and M Letta (2023), “Electoral earthquake: local shocks and authoritarian voting”, European Economic Review, 104464.

Danieli, O, N Gidron, S Kikuchi and R Levy (2023), “Decomposing the rise of the populist radical right: How changes in priorities explain the electoral politics of our time”, VoxEU.org, 29 April.

Norris, P and R Inglehart (2019), Cultural backlash: Trump, Brexit, and authoritarian populism, Cambridge University Press.

Rodriguez-Pose, A (2018), “The revenge of the places that don’t matter”, VoxEU.org, 6 February.

Rodrik, D (2019), “Many forms of populism”, VoxEU.org, 29 October.

Tabellini, G (2019), “The rise of populism”, VoxEU.org, 29 October.