Several countries around the world have recently experienced a rapid rise in inflation as their post-pandemic economic recovery coincided with the emergence of supply-chain bottlenecks and generous government stimulus programmes. This ‘pandemic inflation’ also made its appearance in the euro area. After a disinflationary period that spanned over two decades prior to the pandemic (Draghi 2019), countries in the euro bloc suddenly faced rising inflation in 2021, triggered first by supply-chain disruptions and eventually amplified by the surge in energy prices following the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

In this column, we discuss how this post-pandemic inflationary episode, initially confined to products affected by supply-chain bottlenecks, generalised into a broad-based and persistent phenomenon (Reis 2023). Our analysis in the associated paper (Acharya et al. 2023) indicates that household inflation expectations and firms’ pricing power played a key role in this propagation.

The supply-chain disruptions initially induced the rise of localised inflation

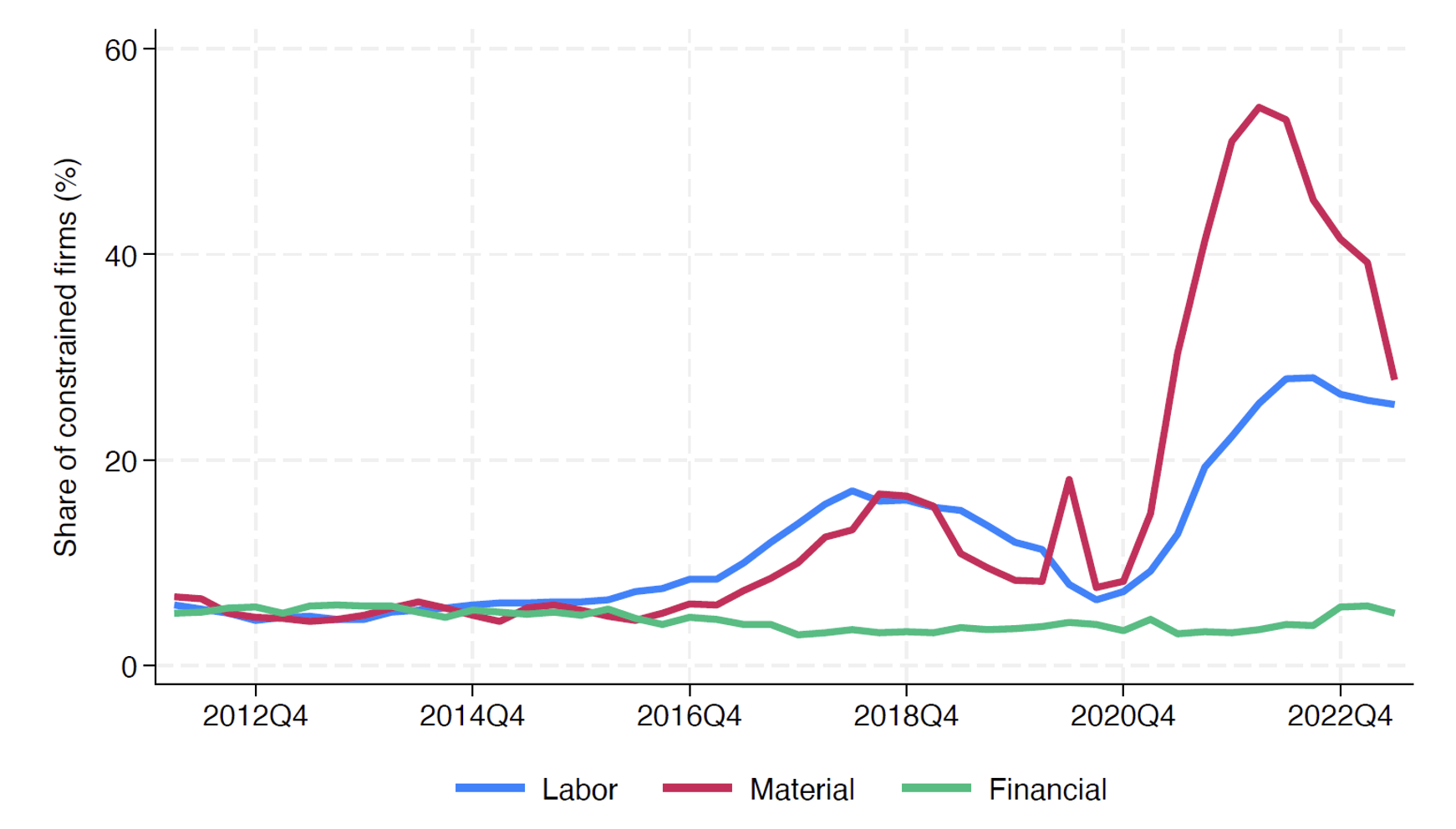

The initial increase in the Consumer Price Index (CPI) in 2021, which preceded the Russian invasion of Ukraine, resembles a textbook case of ‘cost-push’ transmission of supply shocks to inflation. As containers piled up at ports in China due to pandemic lockdowns, some firms struggled to find the inputs they needed to produce, as shown in Figure 1. The resulting higher production costs prompted these firms to increase their prices to maintain their profits (Kalemli-Ozcan et al. 2022).

Figure 1 Rising supply-chain disruptions to firm production in 2021

Note: This figure shows the share of firms answering the following survey question: “What main factors are currently limiting your production?” as follows: (i) shortage of labour, (ii) shortage of material/equipment, (iii) financial constraints. The monthly data is obtained from the Joint Harmonised EU Programme of Business and Consumer firm survey for 27 EU countries.

The causal effect of supply-chain frictions underlying this account is supported in our research by a set of product-country level analyses where CPI growth is positively correlated with sectors’ reliance on imports from Chinese provinces that experienced stringent – and in time-series, staggered – lockdowns. The same empirical work suggests that the inflationary impulse in 2021 remained mostly localised. Even though higher production costs likely spilled over across firms through firm-to-firm linkages, this cost-push inflationary impulse was still somewhat confined within related products.

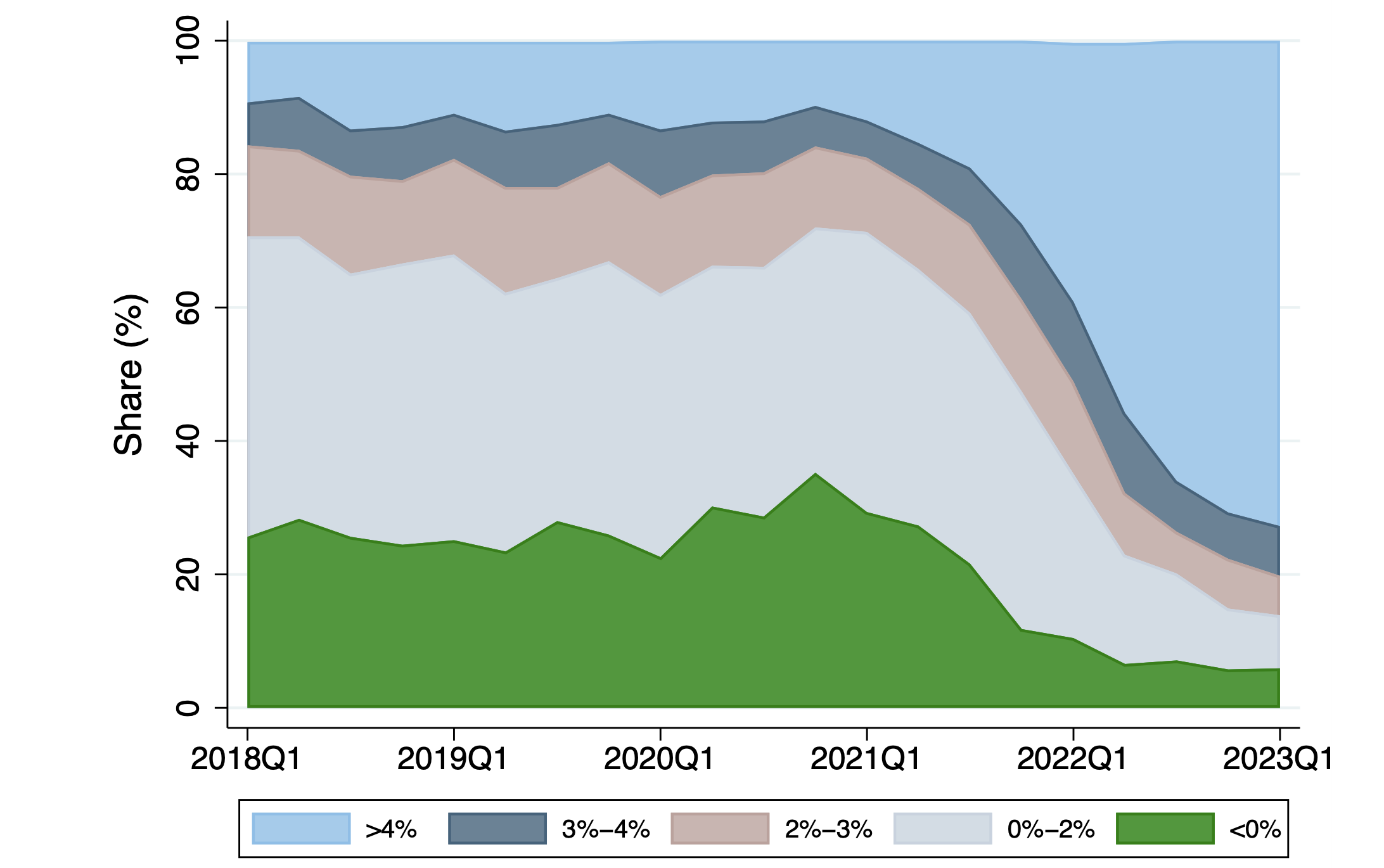

Figure 2, based on product-country level CPI data, paints a consistent picture. By the end of 2021, CPI year-over-year growth was around 5%, with 27% of products experiencing inflation above 4% and 50% of products experiencing inflation below 2%. However, Figure 2 also shows that inflation became broad-based soon after. By the end of 2022, in an environment with CPI year-over-year growth around 9%, 70% of products experienced an inflation above 4%.

Figure 2 Localised inflation in 2021 became broad-based in 2022

Note: This figure is based on product-country level data from Eurostat. Each shaded area shows the share of product-country pairs that, in each quarter, have a specific CPI year-over-year growth as outline in the legend.

Household inflation expectations eventually rose, and inflation became broad-based

Households, following news about supply-chain bottlenecks and experiencing higher prices in their overall consumption basket, began anticipating future generalised inflation starting from the second half of 2021.

We find that in the data, countries with more firms hit by supply-chain disruptions were more likely to experience (i) a higher share of households expecting high future inflation, and (ii) higher individual inflation expectations. In line with a causal interpretation, these correlations are driven by households that had more accurately assessed inflation in the past and are more pronounced in countries with more Google searches about supply-chain bottlenecks.

As households’ inflation expectations increased, so did actual inflation in sectors not affected by supply-chain disruptions. This observation holds both in countries with a high share of employees covered by a collective bargaining agreement and in countries with a lower adoption of the same agreements, suggesting that broad-based inflation was not primarily driven by firms anticipating a future pick-up in labour costs.

Interestingly, the sudden surge in energy prices following the Russian invasion of Ukraine also does not explain the initial effect of supply-chain bottlenecks on inflation nor its subsequent generalization into a broad-based phenomenon. First, supply-chain disruptions were largely unrelated to the energy shock in the initial ‘cost-push’ transmission (in fact, they are orthogonal to each other in our regressions). Second, the energy shock seems to play a smaller role in stimulating broad-based inflation compared with supply-chain disruptions.

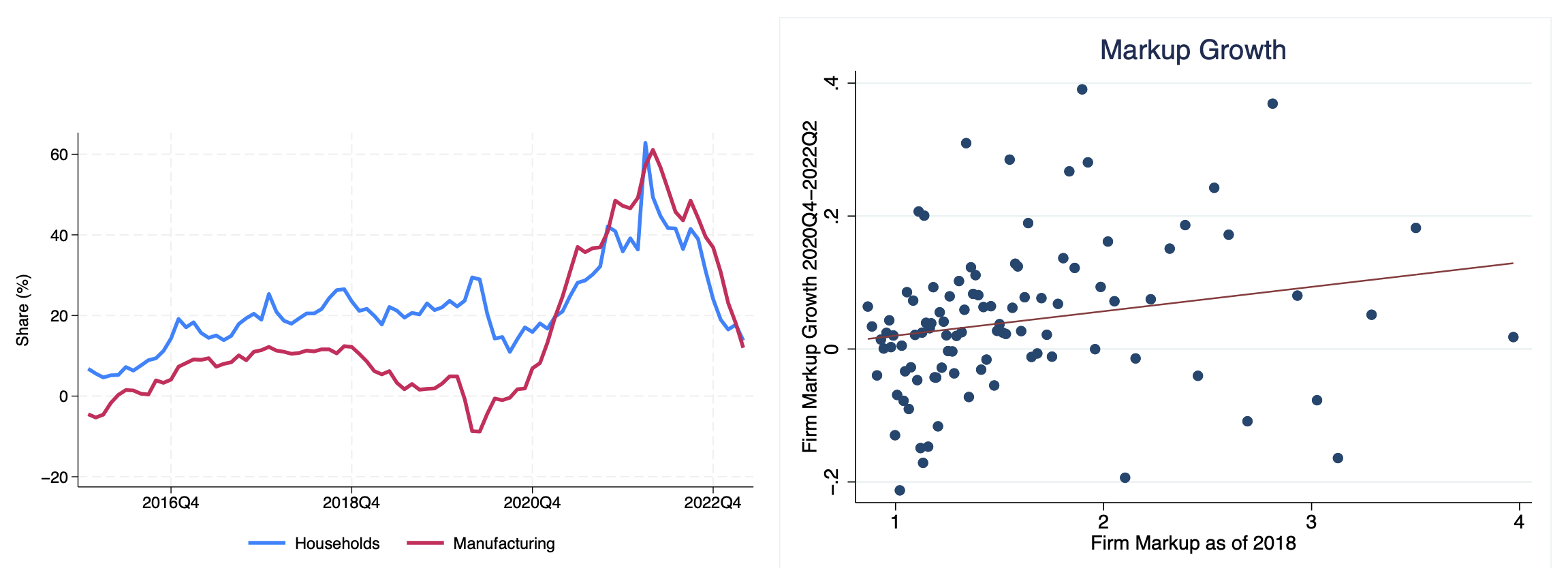

Firms with pricing power sustained, and some even increased, their markups

Figure 3 shows that, as inflation expectations surged in 2021 and in the first part of 2022 (left panel), firms with pricing power sustained, and some even increased, their markups in product prices. The scatter plot on the right shows that most firms with high pricing power prior to the pandemic managed to sustain their markups from 2020:Q4 to 2022:Q2. In a context with increasing production costs, this dynamic implies that firms with pricing power effectively improved their gross margins per unit sold.

Figure 3 Steady or increasing markups for firms with pricing power as inflation expectation rose

Note: The left panel shows households’ and manufacturing firms’ inflation expectations, measured as the share of households/firms expecting prices to increase more rapidly minus share of households/firms expecting inflation to fall over 12 months (for households) and 3 months (for manufacturing firms). The data source is the monthly survey on euro area households’ and firms’ inflation expectations. The right panel shows a binscatter plot of the growth in markups from 2020:Q4 to 2022:Q2 against the ex-ante markups measured in 2018. Markups are calculated following De Loecker et al. (2020).

In other words, firms with high pricing power managed to increase their prices more during both the initial ‘cost-push’ burst of inflation and the subsequent emergence of broad-based inflation, even after supply-chain disruptions eventually eased. We conjecture that in this second phase, households with high inflation expectations likely became less informed about the distribution of prices across firms and products and, as a result, became willing to purchase goods and services at higher prices (Benabou and Gertner 1993, Tommasi 1994). Perhaps not surprisingly, firms with pricing power likely exploited this lower price elasticity of demand.

Our analysis documents a set of correlations consistent with this conjecture. First, firms with high pricing power maintained or even increased their markups when facing supply-chain disruptions to production, and when aggregate demand, measured using firms’ order book information, was sufficiently high. Second, firms with high pricing power experienced a reduction in markups if located in sectors and countries with well-functioning supply-chains and limited demand. Third, as inflation expectations increased, firms with high pricing power maintained, or even increased, their markups irrespective of whether they were affected by supply-side disruptions.

An argument for proactive policy response.

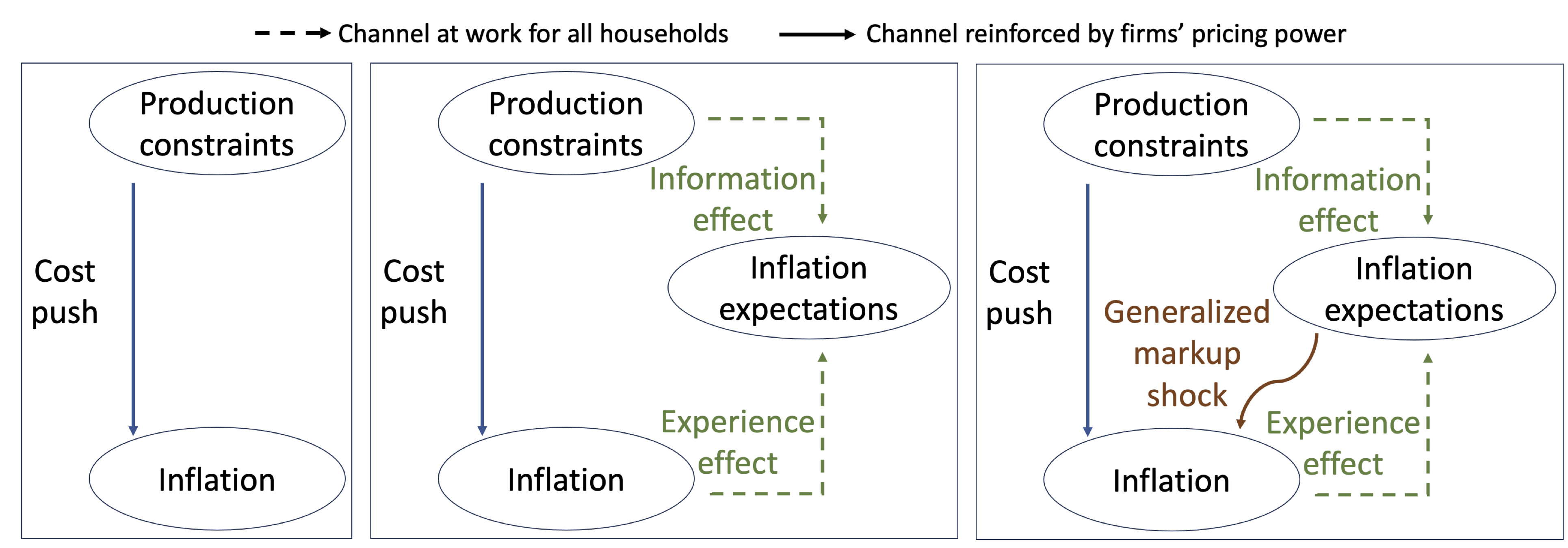

Our account of the pandemic inflation in the euro area has several important implications for policy. Above all, the combination of high inflation expectations and firm pricing power might create feedback loops (see Figure 4). As some firms with pricing power raise their prices, households might increase their inflation expectations leading, in turn, to sustained generalised inflation, fuelled further by firms with pricing power. While a single shock might set it in motion, this loop is sustained by its intertwined forces and might thus persist even after the initial shock has subsided. Hence, the policy response to supply-side inflationary pressures might need to be proactive considering that localised inflation impulses might generalise and spiral upwards via an interaction of firms’ pricing power and household expectations.

Figure 4 From supply-chain disruptions and localised inflation to high inflation expectations and broad-based inflation

Authors’ note: The views expressed in this column are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, the Federal Reserve System, or any of their staff.

References

Acharya, V V, M Crosignani, T Eisert and C Eufinger (2023), “How do supply shocks to inflation generalize? Evidence from the pandemic era in Europe,” CEPR Discussion Paper No. DP18530.

Benabou, R and R Gertner (1993), “Search with learning from prices: Does increased inflationary uncertainty lead to higher markups?”, The Review of Economic Studies 60: 69–93.

De Loecker, J, J Eeckhout and G Unger (2020), “The rise of market power and the macroeconomic implications,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 135(2): 561–644.

Draghi, M (2019), “Twenty years of the ECB’s monetary policy,” speech at the ECB Forum on Central Banking, Sintra.

Kalemli-Ozcan, S, A Silva, M A Yildirim and J di Giovanni (2022), “Global supply chain pressures, international trade, and Inflation,” CEPR Discussion Paper No. DP17449.

Reis, R (2023), “The burst of high inflation in 2021-22: How and why did we get here?”, in How Monetary Policy Got Behind the Curve--And How to Get it Back, Hoover Institution Press, pp. 203-250.

Tommasi, M (1994), “The consequences of price instability on search markets: Toward understanding the effects of inflation,” The American Economic Review 84(5): 1385–1396.