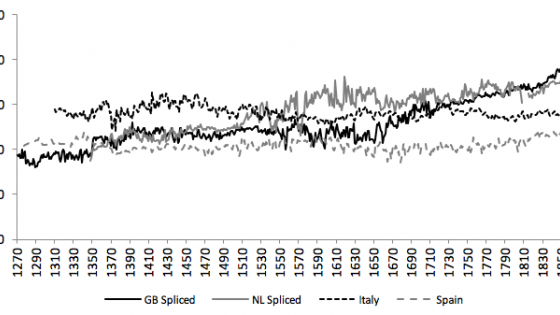

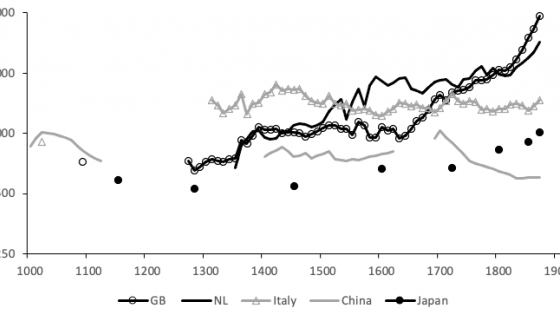

Modern advanced economies share long, prosperous expansions and short, mild contractions. When did the modern business cycle first emerge? Until recently, systematic data-based analysis of business cycles could only be conducted on very modern data, and even for much of the 19th century, this was only possible using disaggregated data offering partial coverage of the economy (Burns and Mitchell 1946). In the last two decades or so, there has been dramatic progress in the quantification of economic activity between the 14th and 19th centuries, resulting in estimates of aggregate GDP. This has now led to a rich literature on economic growth, shedding light on the European Little Divergence, or reversal of fortunes between Mediterranean Europe and the North Sea area, as well as the Great Divergence between Europe and Asia (Broadberry 2021). For a growing sample of European economies, these data are available at annual frequency, so that the time is now ripe to conduct business cycle analysis to complement the study of economic growth and also to explore the interrelationships between short run fluctuations and long run trends.

Data and methods

In recent research (Broadberry and Lennard 2023), we compiled a data set of historical national accounts for nine European economies between 1300 and 2000 and developed an algorithm that mimics the turning points selected by business cycle dating committees (Broadberry et al. 2023), which we applied to the log level of real GDP per capita for each economy.

Business cycle facts

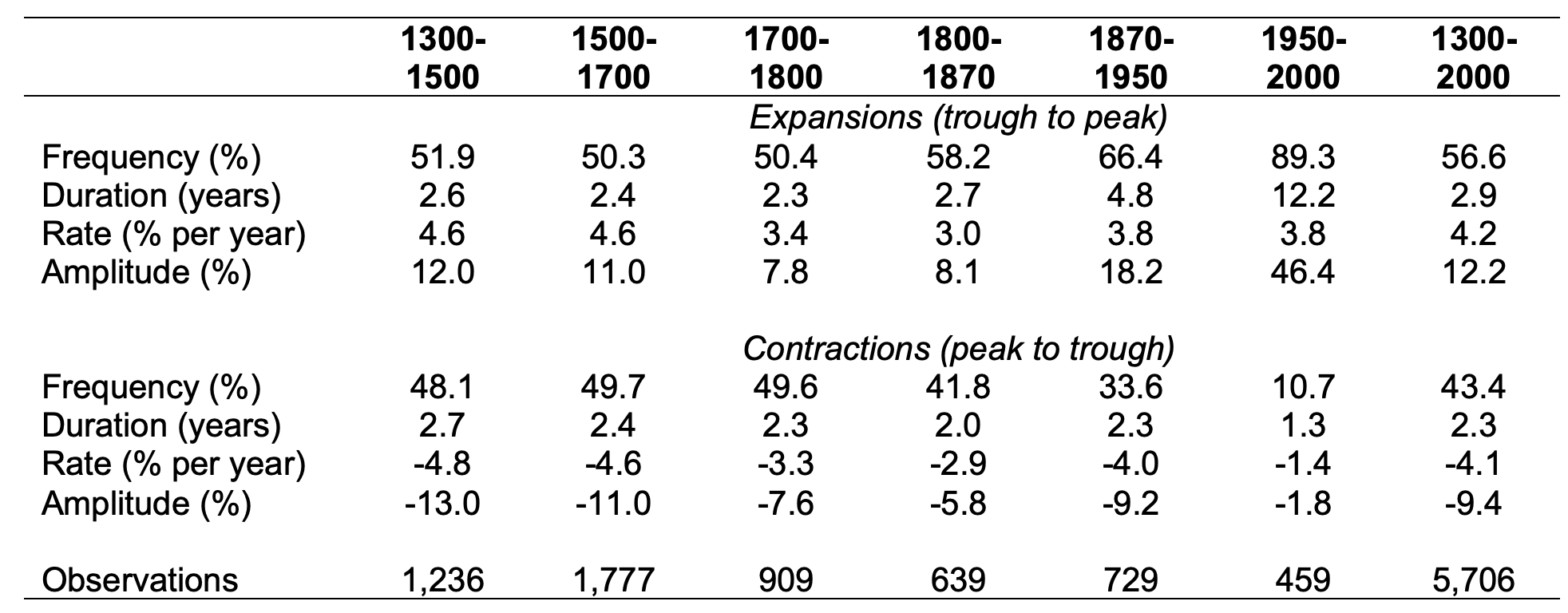

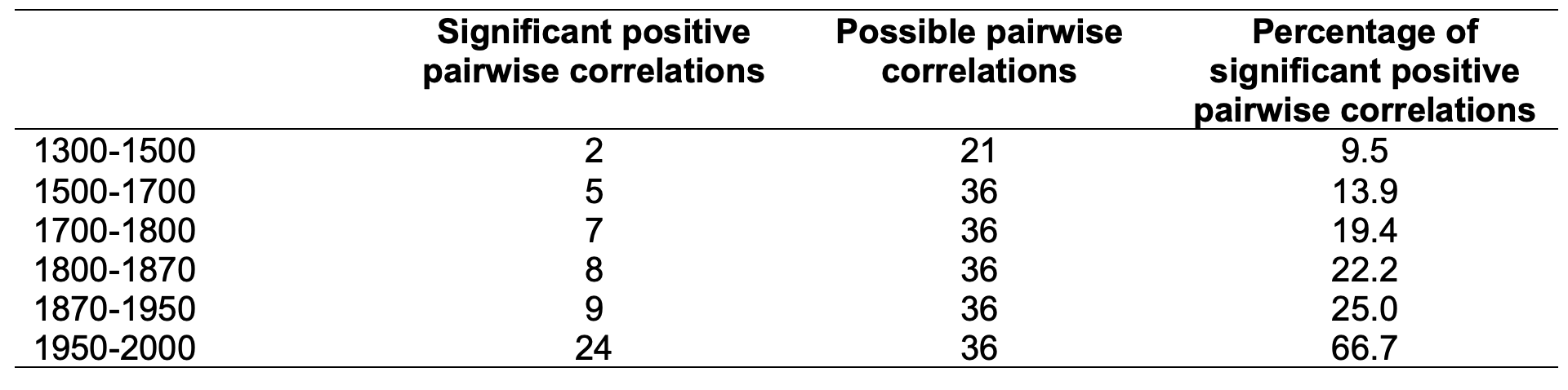

The results are presented in Table 1. Beginning with the post-war period (1950-2000), we find that the modern business cycle is characterised by four features. The first is that expansions are far longer – and therefore more frequent – than contractions, with expansions lasting 12 years and contractions just over one year on average. The second is that the rate of growth during expansions is close to 4% per year and just over -1% during contractions. Third, the implication of a higher duration and rate is that the amplitude of expansions is 46% and less than -2% for contractions. The fourth, shown in Table 2, is that modern business cycles are highly synchronised: two-thirds of the country pairs in our sample share a positive and statistically significant correlation of GDP per capita growth. The modern business cycle is therefore highly asymmetric, with longer expansions, faster rates and greater amplitudes than contractions, and closely synchronised across countries.

Table 1 The European business cycle

Notes: This table shows the frequency, duration, rate, and amplitude of European business cycles in GDP per capita between 1300 and 2000 for nine European economies.

Moving back to the medieval (1300-1500) and early modern (1500-1700) periods, these patterns did not hold. The pre-modern business cycle was short and volatile with phase lengths of less than three years and with high (absolute) average growth rates; symmetric with a 50:50 split between expansions and contractions and comparable durations, rates, and amplitudes across phases; and out of synch with other economies.

Table 2 International co-movement

Notes: This table shows the international co-movement of logarithmic growth rates of GDP per capita between 1300 and 2000 for nine European economies.

The transition to the modern business cycle occurred in the 19th century, when the symmetry and independence of the Middle Ages began to wane. The shift was subtle at first but was dramatic by the post-war period.

The short run in the long run

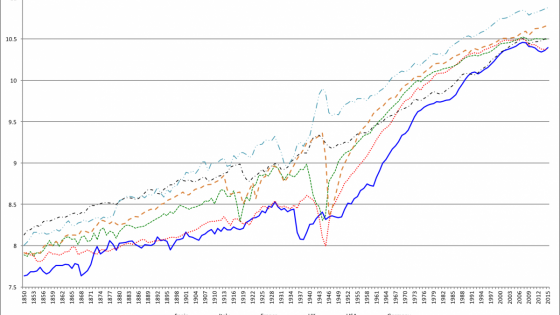

The 19th century marks the onset of the modern business cycle and modern economic growth. Are the two related? Long run economic growth is the cumulation of some of the short run statistics reported in Table 1: growth is equal to the product of the frequency of expansions and the rate of expansions plus the product of the frequency of contractions and the rate of contractions (Broadberry and Wallis 2017).

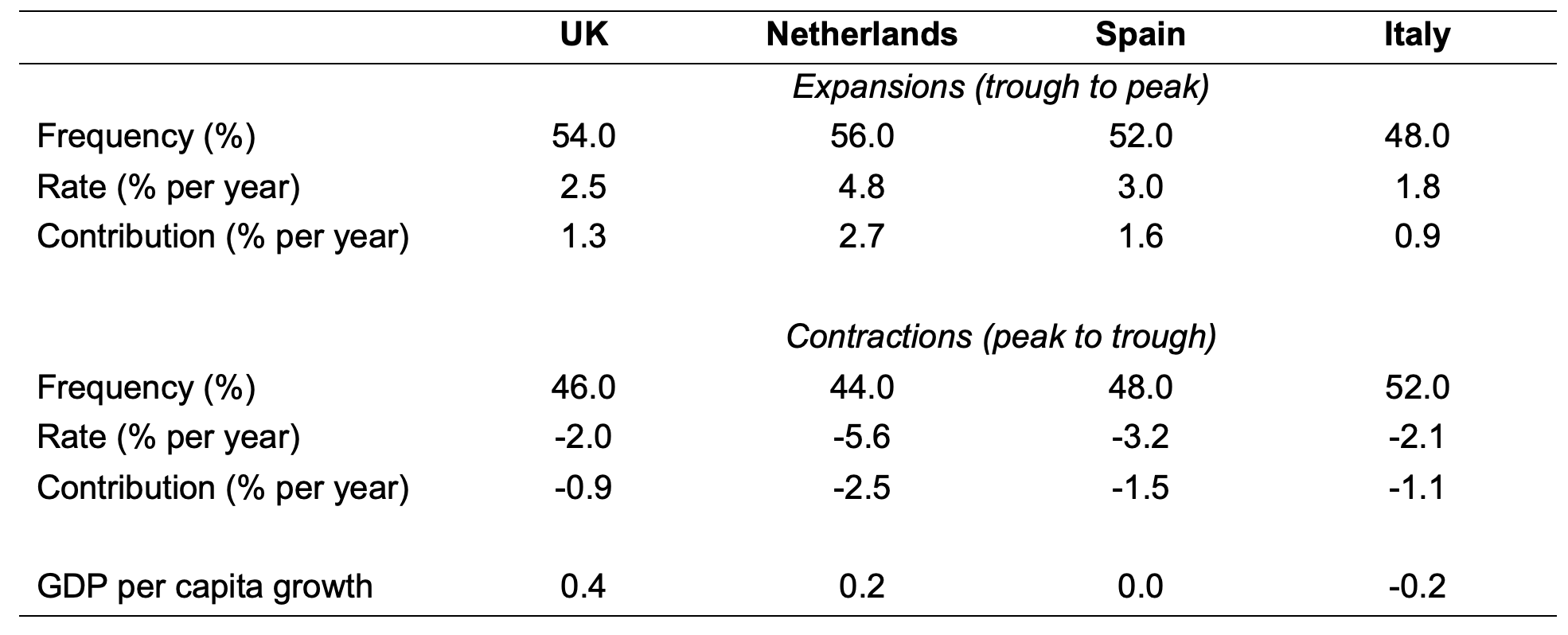

Table 3 applies this idea to the Industrial Revolution when Britain made the transition to modern economic growth and ushered in the modern world. We see in the final row that GDP per capita growth was slightly faster in Britain than in the Netherlands, and substantially faster than in Spain and Italy. This was mainly due to the fact that Britain had the lowest rate and contribution of contractions, despite also having a low rate and contribution of expansions. Therefore, we see that the crucial evolution of the business cycle for long-run economic performance lay in the dampening of contractions rather than in the acceleration of expansions.

Table 3 Contributions of expansions and contractions to long run economic performance, 1751-1800

Notes: This table shows the frequency, rate, and contribution of business cycles in GDP per capita between 1751 and 1800 for four European economies.

Conclusions

Not only was life short and violent in the distant past, but so was the business cycle. A good year was followed by bad, resulting in low growth and high volatility. The 19th century was the turning point, as the losses from contractions were minimised while the gains from expansions were preserved, which generated economic growth and rising living standards. Economists in the West have tended to assume that the transition to this pattern of rising living standards is irreversible, particularly following the very low incidence of contractions during the second half of the 20th century. However, the return of a series of major contractions during the 21st century calls into question this assumption. Do we now need to pay as much attention to the role of institutions in creating resilience to contractions as we do to the generation of new ideas driving expansions (Haldane 2018)?

References

Broadberry, S (2021), “Accounting for the Great Divergence: Recent findings from historical national accounting”, VoxEU.org, 20 April.

Broadberry, S, J S Chadha, J Lennard and R Thomas (2023), “Dating business cycles in the United Kingdom, 1750–2010”, Economic History Review 76: 1141–1162.

Broadberry, S and J Lennard (2023), “European business cycles and economic growth, 1300-2000”, CEPR Discussion Paper 18502.

Broadberry, S and J Wallis (2017), “Growing, shrinking and long-run economic performance”, VoxEU.org, 5 July.

Burns, A F and W C Mitchell (1946), Measuring business cycles, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Haldane, A (2018), “Ideas and institutions – A growth story”, Bank of England.co.uk, 23 May.