Editors' note: This column is part of the Vox debate on the economic consequences of war.

The ongoing war in Ukraine has challenged European citizens and decision-makers. Will the EU, together with its allies, be able to provide a strong and uniform response? Or will it fracture into different groups that cannot manage to cooperate?

The EU is a particularly interesting case of a political union, because of its historical importance, its grand ambition, and the scale of the challenges for successful cooperation. Composed of member states that differ tremendously in language, culture, and history, it is quite remarkable how much has been achieved over the last decades.

However, many struggles remain, in particular in times of crisis. One key issue for more – and successful – cooperation is the question of a common European identity. Currently much of EU politics is still guided by national considerations (Gehring and Schneider 2018). The European debt crisis, for instance, revealed the challenge of establishing insurance mechanisms and redistribution. A stronger joint identity helps to establish trust and compassion within a group – a key condition for successful cooperation – and the willingness to share risks and support each other.

The determinants of identity have recently become a popular topic of economics research. In the EU context, Dehdari and Gehring (2022) show that negative historical experiences, including interstate war and tensions with the central state, are a key factor influencing the strength of regional identities. Gehring (2021) shows that support for the EU, both in surveys and actual voting, can also be explained by these negative experiences and the role of the EU in mitigating tensions between regions and central states. For Eastern EU members, their membership and support are also crucially related to historical experiences with the Soviet Union.1

Threats, identity, and cooperation

The full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine has also suddenly increased the perceived threat posed by a potential invasion of Russia for EU member states. Whether such outside threats lead to a stronger common identity of a group, and more cooperation, has been a crucial question for a long time.

Anecdotally, the foundation of many nations was fostered by an outside threat. Think about the American War of Independence against the British Empire or the foundation of a united Germany after a war against France. The EU itself and its predecessors were developed at least partly as a response to the military threat posed by the Soviet Union, and the Cold War is supposed to have had a unifying effect (Bordalo et al. 2021)

However, there has been no causal evidence to support the claim so far outside a laboratory setting. There were two main challenges to answer this question causally using real world examples. The first concerns the ability to distinguish the effect of an increased threat from other shocks. For instance, increased threats are often accompanied by direct conflict, destruction, or actual cooperation, making it hard to know whether any effect is due to the conflict or the threat (Todo and Kashiwagi 2021).

Second, relying purely on comparisons of before and after the threat runs into the risk of identifying a spurious correlation, but not necessarily a causal relationship. Hence, despite the popularity of the threat-identity-hypothesis, there was no causal evidence for it to be a real phenomenon and not just an ex post historical narrative.

Quasi-experimental evidence from the Russian invasion of Ukraine 2014

In a recent paper (Gehring 2022), I use the Russian invasion of Crimea and parts of the Donbas region in 2014 as a natural experiment to provide such evidence. Three features allow this. First, while the invasion was in Ukraine, it clearly affected the perceived threat posed by Russia to EU member states as well. Second, the invasion itself and, in particular its precise timing, were unexpected at the time and can thus be considered as an exogenous shock (Gorodnichenko and Roland 2014, Gylfason and Wijkman 2014, Gylfason et al. 2014).

Third, there were clear differences in the intensity of the threat between EU member states, generating cross-sectional differences in the intensity of that shock. I argue that the shock was largest for Estonia and Latvia, as these two states have both a direct land border with Russia and a sizeable Russian minority population (used to justify invasions by Russia).

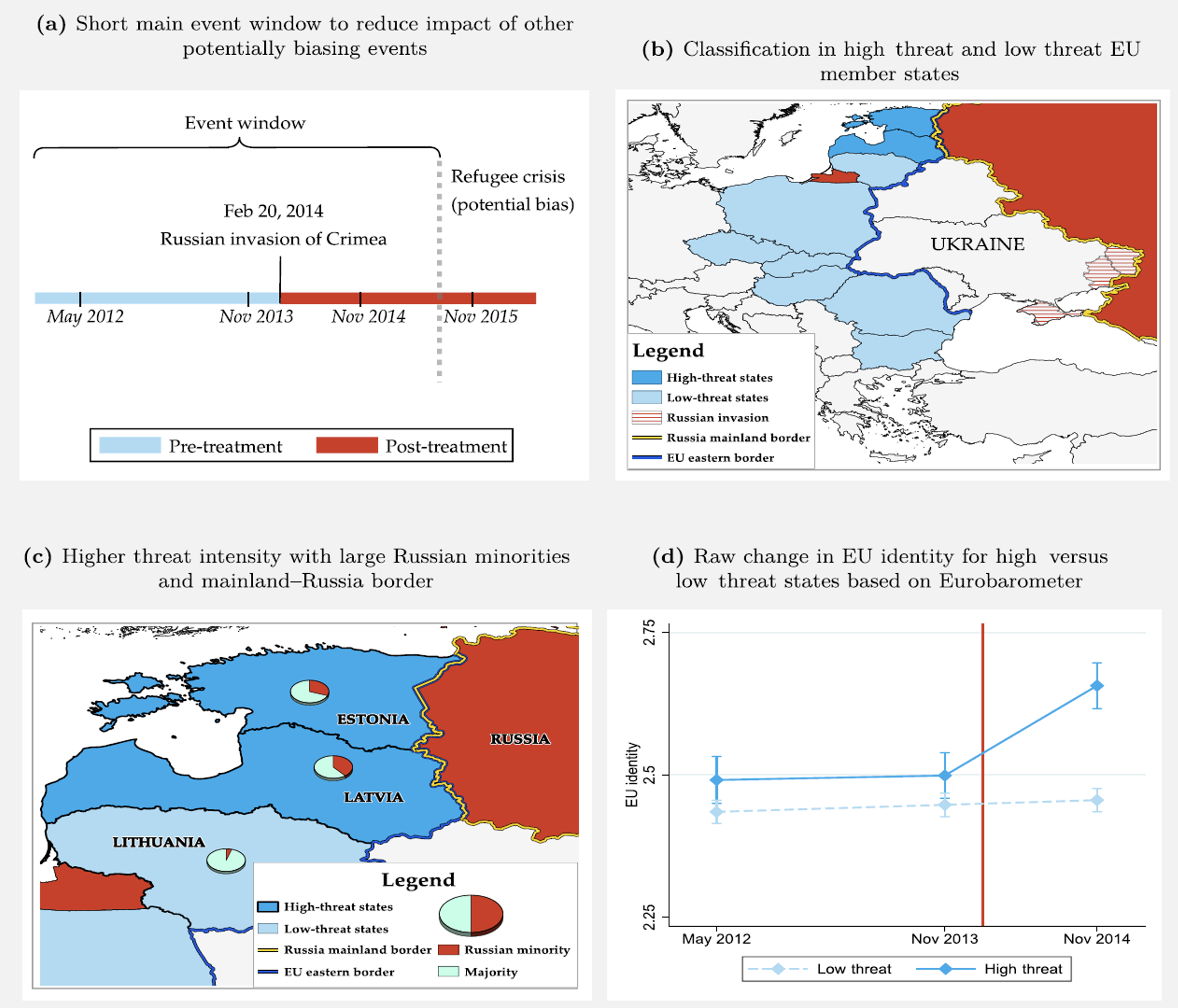

Figure 1 Quasi-experimental design

Notes: Figure 1(a) reports a timeline for our analysis. Figure 1(b) shows the treatment and control groups. Maps are based on Eurostat (2016). Minority shares in Figure 1(c) are identified based on language. Figure 1(d) shows a simple average difference in our main variable. Figures show 95% confidence intervals of averages.

Using both qualitative and quantitative evidence based on text analysis of newspaper articles and internet searches, I validate these assumptions. Citizens everywhere in the EU feel more threatened, but the intensity varies in line with this expectation.

With data from the bi-yearly Eurobarometer survey, I then examine empirically using a difference-in-differences framework whether there is a causal effect of the increased threat on EU identity, in-group trust, and willingness to cooperate. The outcomes are based on a representative sample of EU citizens for each member state.

The results clearly indicate a qualitatively and quantitatively significant increase in a common EU identity. To put things into perspective, the increase due to the increased Russian threat is of equal size to the initial difference between Poland (strong EU identity before) and Hungary (weaker EU identity). It is more than twice the initial difference between Germany (strong initial identity) and France (weaker initial identity).

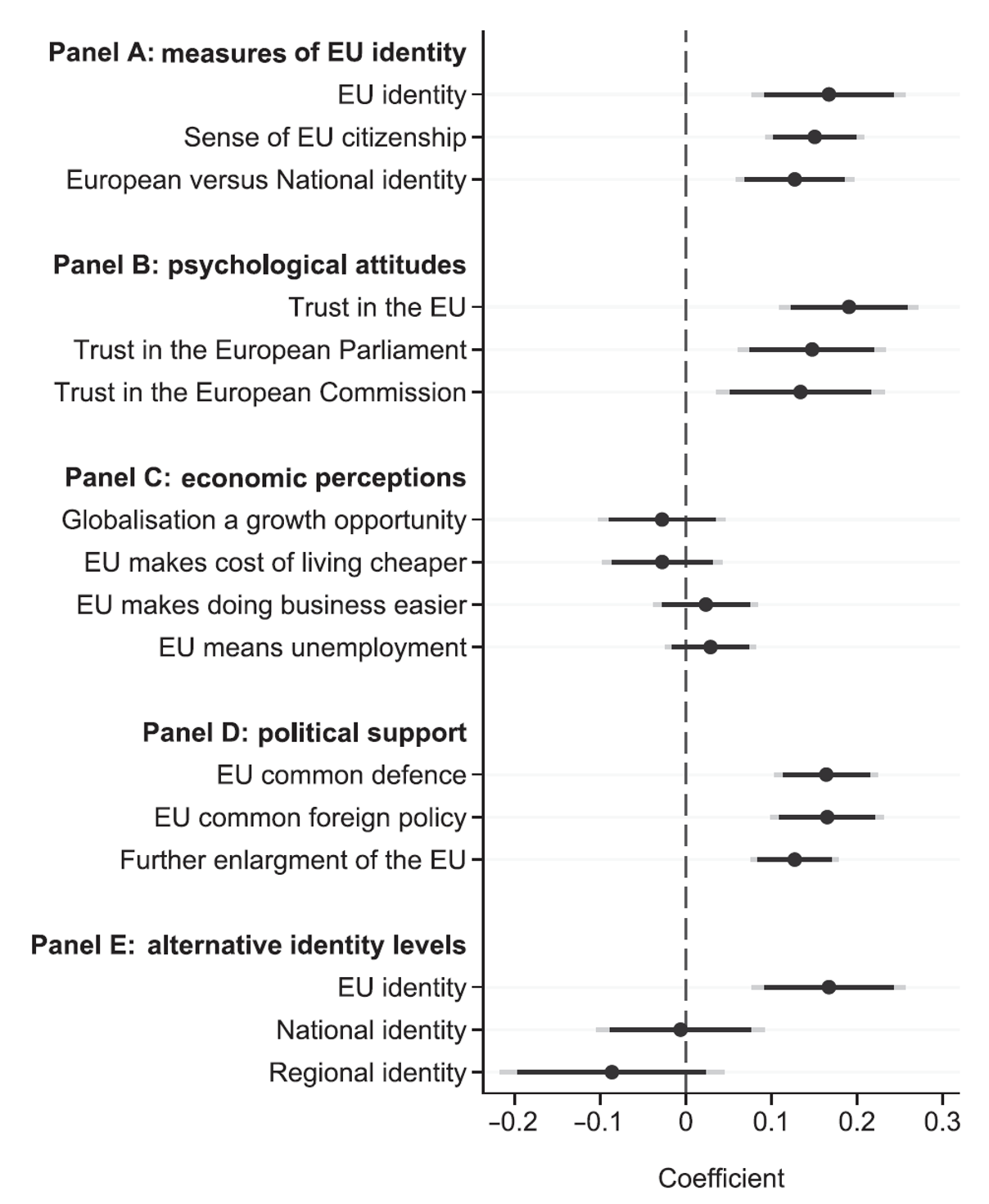

Figure 2 Main results

Notes: Figure displays difference-in-difference coefficients measuring the impact of the increased Russian threat, with corresponding 90% and 95% confidence intervals (95% in lighter grey). All outcomes are standardised. All regressions control for individual characteristics including gender, age, education level, labour market status, urban versus rural area, marital status and the presence of children, time fixed effects, and member state fixed effects. Standard errors are clustered at the regional level. The number of pre-treatment measurements is between two and five, the number of post-treatment observations is between one and three, depending on the availability of variables. The number of observations for EU identity is 24,885. For the other outcomes, it ranges from 25,569 to 68,408.

Further estimations highlight that the effect is persistent over time. It is stronger for age cohorts that had personal experiences with the Soviet Union, and for those who have personal or indirect experiences with state persecution during the Soviet era.

As predicted by social psychological theories, the increased identity translates into higher trust in EU institutions, as well as higher support for cooperation at the EU level. This willingness to cooperate is not limited to defence policy, rather it extends to areas like a common foreign policy, taxes, and regulation.

Assessing the impact of the Russian invasion of Ukraine 2022

How can we assess the ongoing full-scale invasion by Russia? Given the extent of the operation, the threat should be at least as large and trigger a sizeable response. Eurobarometer survey results are not yet available for a quantitative evaluation. However, a preliminary (‘flash’) Eurobarometer indicates a response in line with the results in my paper.

Politically, Eastern Europeans are more united than ever before. Even states with a strong prior affiliation to Russia, like Bulgaria, took a clear stance. Western states like Italy and Germany were initially hesitant but, backed by public opinion, both governments did finally align with other members for a joint response.

Of course, there can be incentives against common action that might not be overcome by a strengthened joint identity. Hungary provides a sad example in this regard. State-controlled media giving a biased perspective of the actual events also have the potential to moderate the response. However, unlike in earlier times as part of the Visegrád Group, Hungary is now at least clearly the outcast also among eastern EU member states.

The uniting effect of facing an outside threat thus seems to be clearly visible, even without additional quantitative evidence. Finland and Sweden are bound to give up their neutrality and join NATO. Denmark is likely to overturn its opt-out from EU defence policy in an upcoming referendum. The future will show whether a stronger European identity will also help to foster cooperation is areas going beyond defence and foreign policy.

There may be hope. Many studies indicate that a common identity is a prerequisite to overcome collective action problems and provide, for instance, a common social security system (Bagues and Roth 2021) Higher trust can lead to a positive feedback loop of more successful cooperation and policies (De Grauwe 2012). But in the end, it is up to the EU Commission and member state governments to turn this support into functioning institutions and policies that justify the trust of its citizens.

References

Bagues, M and C Roth (2021), “Interregional contact and national identity”, VoxEU.org, 3 January.

Bordalo, P, M Tabellini and D Yang (2021), “Issue salience and political stereotypes”, VoxEU.org, 20 January.

De Grauwe, P (2012), “Trust between Eurozone leaders can create self-fulfilling positive outcomes”, VoxEU.org, 13 July.

Dehdari, S and K Gehring (2022), “The Origins of Common Identity: Evidence from Alsace-Lorraine”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 14(1): 261–292.

Fouka, V and H-J Voth (2013), “Reprisals remembered: German-Greek conflict and car sales during the Euro crisis”, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 9704.

Gehring, K and S A Schneider (2018), “Towards the greater good? EU commissioners’ nationality and budget allocation in the European Union”, American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 10(1): 214–239.

Gehring, K (2021), “Overcoming History through Exit or Integration - Deep-Rooted Sources of Support for the European Union”, American Political Science Review 115(1): 199-217.

Gehring, K (2022), “Can External Threats Foster a European Union Identity? Evidence from Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine”, The Economic Journal 132(644): 1489-1516.

Gorodnichenko, Y and G Roland (2014), “What is at stake in Crimea?”, VoxEU.org, 10 March.

Gylfason, T and P Wijkman (2014), "Meeting Russia’s challenge to EU’s Eastern Partnership”, VoxEU.org, 25 January.

Gylfason, T, I Martínez-Zarzoso and P Wijkman (2014), “A way out of the Ukrainian quagmire”, VoxEU.org, 14 June.

Ochsner, C and F Rösel (2017), “Activated history – The case of the Turkish sieges of Vienna”, CESifo Working Paper Mo. 6586.

Todo, Y and Y Kashiwagi (2021), “Impacts of natural disasters on perceptions of others”, VoxEU.org, 21 December.

Endnotes

1 Current events can activate or strengthen such dependencies, as shown by Ochsner and Roesel (2017).