Over half the world’s population live in the 103 countries that require cigarette packages to carry graphic warning labels about the health consequences of smoking (WHO 2023: 66). The US is not one of the 103 countries, despite the fact that the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act of 2009 mandated graphic warning labels. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) proposed a set of graphic warning labels, but the cigarette manufacturers challenged the requirement in the courts. In 2012, a federal district court found that the proposed labels were unconstitutional and violated the free speech rights of the manufacturers.

In 2020 the FDA proposed new graphic warning labels and articulated a more specific government interest statement (Federal Register 2019, 2020). The cigarette manufacturers again challenged the new proposed warnings, largely on the same basic premise of their earlier challenge (RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company v. FDA, No. 6:20-cv 00176). The court concluded again that the compelled labels do not survive scrutiny and are unconstitutional (RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company v. FDA, No. 6:20-cv 00176 Opinion and Order, p. 23). In February 2023, the FDA announced its intention to appeal this decision.

Research in public health, economics, and other disciplines provides a large evidence base on the effectiveness of graphic warning labels and other tobacco control policies to reduce smoking and improve global health. In a meta-analysis of studies that use an experimental protocol, Noar et al. (2016) found evidence that graphic warnings were more effective in attracting and holding attention, eliciting cognitive and emotional reactions, driving negative attitudes toward smoking, and generating intentions not to smoke. However, almost all the included studies focus on the precursors to behavioural change rather than smoking outcomes.

Another set of studies evaluates changes in smoking attitudes and/or behaviour after the introduction of required graphic warning labels in countries that enacted them. For example, research concludes that after graphic warning labels were introduced in Canada, consumers were more likely to notice the labels, think about quitting, and be more knowledgeable about the health consequences of smoking (Hammond et al. 2003, Hammond and McDonald et al. 2004, Hammond and Fong et al. 2004, Hammond et al. 2007, and Hammond 2011).

Monárrez-Espino et al. (2014) conducted a systematic review of studies of graphic warning labels that focus directly on smoking outcomes. They conclude that the empirical evidence for or against graphic warning labels is insufficient and that any impact would be modest. Their conclusion contrasts with the WHO’s (2023) support for graphic warning labels. Such controversies are not uncommon in tobacco control research. For example, van Ours and Palali (2017, 2019) conclude that non-price tobacco control policies in 11 EU countries do not seem to discourage youth from taking up smoking, which again contrasts with WHO support for the policies.

The US legal dispute about graphic warning labels involves questions about whether they work to discourage smoking, as well as how they work. The 2012 ruling against the warning labels focused, in part, on the finding that the government was not simply attempting to inform consumers about the risks of smoking but was instead trying to emotionally persuade consumers not to smoke – and thus had overreached its constitutional authority (RJ Reynolds Tobacco Co. v. US Food and Drug Administration 2012, 696 F.3d 1205, 1214 (DC Cir 2012)). The court determined that the government’s stated interest was to “both discourage non-smokers from initiating cigarette use and to encourage current smokers to consider quitting” (Federal Register 2011: 36630). In surprisingly harsh language, the appellate court states that “[t]he FDA has not provided a shred of evidence – much less the substantial evidence required by the APA [Administrative Procedures Act] – showing that the graphic warnings will directly advance its interest in reducing the number of Americans who smoke” (RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company v. Food and Drug Administration 2012: 12).

In its 2020 proposal, the FDA’s new stated interest avoids claiming that the goal of the government action is to reduce smoking rates. Instead, the FDA proposed a new set of graphic warnings designed with a narrower goal to inform consumers of some of the “lesser-known but serious health risks of smoking” (Federal Register 2019: 42754). The cigarette manufacturers allege that, as with the originally proposed graphic warning labels, the new graphic warning labels are designed to evoke negative emotions and argue that this crosses the line into “governmental anti-smoking advocacy” (RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company v. FDA, No. 6:20-cv 00176, p. 1).

New evidence on the potential impact of graphic warning labels in the US

In a recent paper (Kenkel et al. 2023), we report new evidence from an empirical study that combined an online experiment about graphic warning labels with a discrete choice experiment about consumers’ stated preferences between cigarettes, e-cigarettes, and quitting. The sample consisted of 1,171 US adult smokers. In the graphic warnings experiment, half of the subjects were shown one of the new graphic labels while the other half made up the control group and were shown one of the current Surgeon General’s text warning labels. By embedding the graphic warnings experiment in a discrete choice experiment, we study the impact of graphic warning labels on hypothetical cigarette purchases in a semi-realistic market context.

We also study how graphic warning labels work: we directly examine whether changes in choices associated with being exposed to the graphic warning label are driven by (a) improved knowledge about the health risk featured in the warning, or (b) levels of fear and disgust when seeing the warning label.

Our empirical analysis examines the choices that consumers who currently smoke cigarettes would make when facing different hypothetical scenarios in the discrete choice experiment. The scenarios vary in the price of cigarettes, the price of e-cigarettes, the availability of different flavours of e-cigarettes, the warning labels on e-cigarettes, and the nicotine content of e-cigarettes.

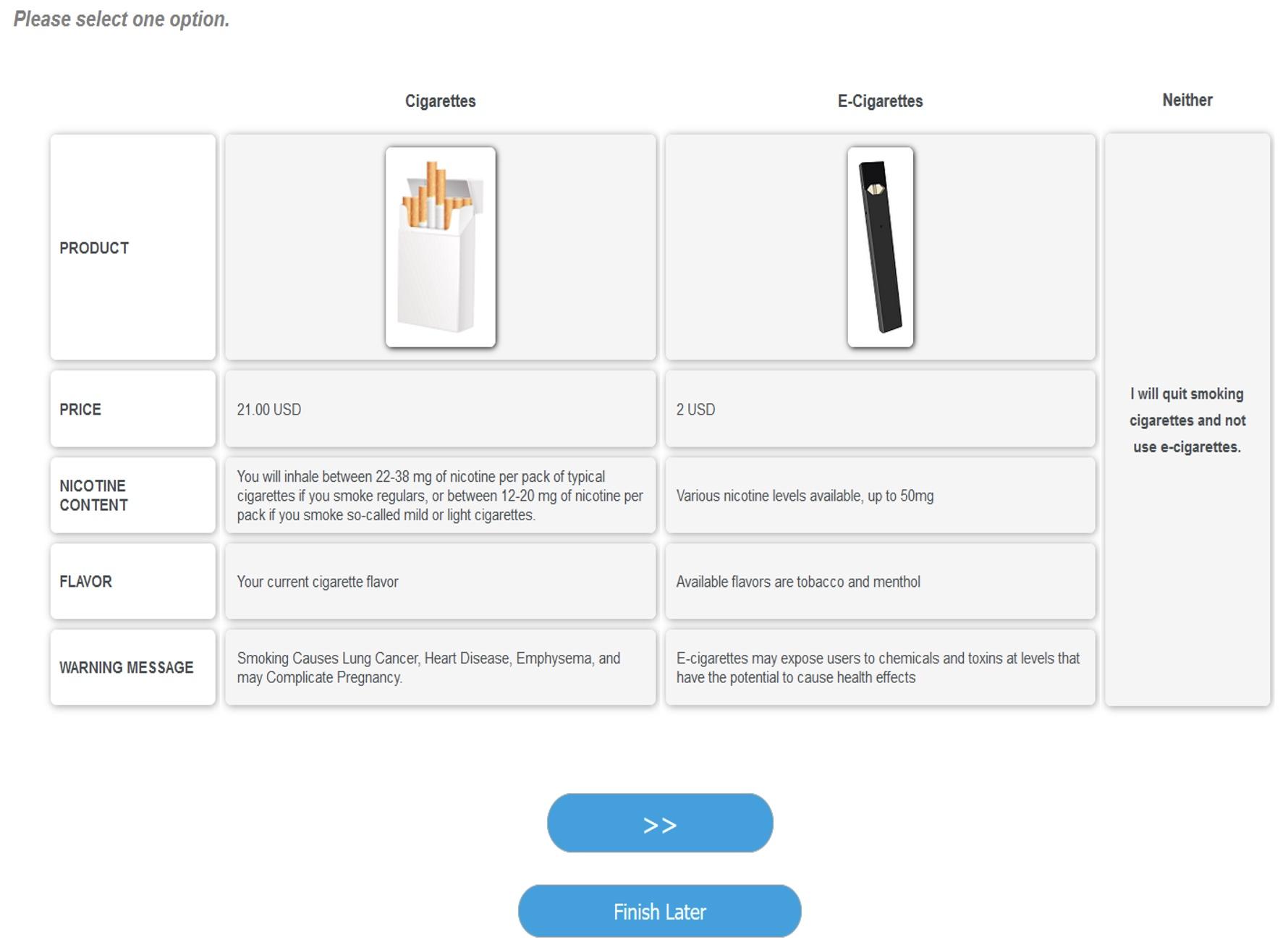

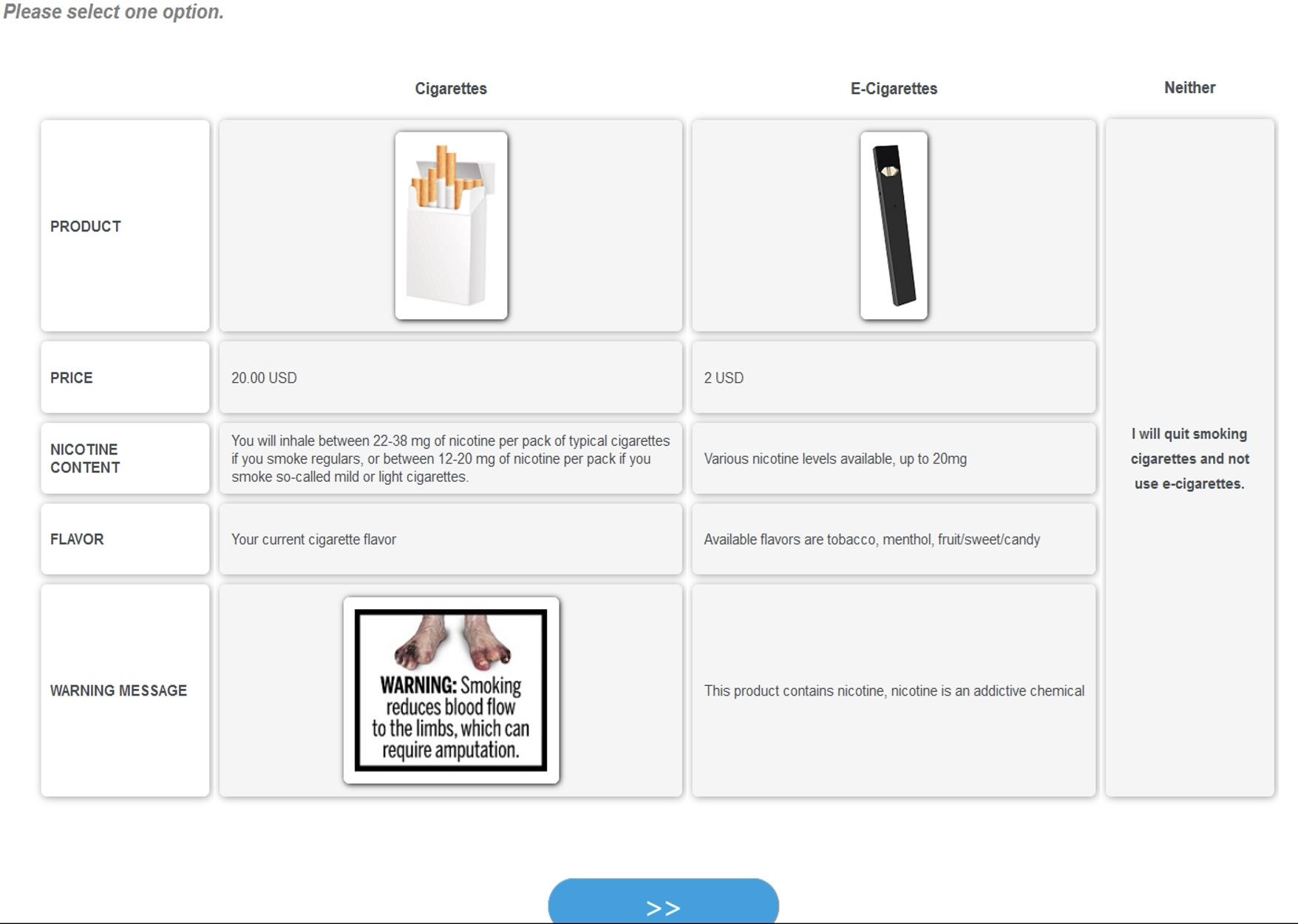

Figure 1A shows a typical scenario for the half of the sample who saw one of the current Surgeon General’s text warnings; Figure 1B shows a typical scenario for the other half of the sample who saw the proposed FDA graphic warning labels featuring amputated toes with the accompanying message “Smoking Reduces Blood Flow to the Limbs, Which May Require Amputation”.

Figure 1 Scenario presentations to respondents

(A) For respondents randomly assigned to the Surgeon General cigarette warning label

(B) For respondents randomly assigned to the FDA graphic warning label

Immediately following the scenarios, subjects were then asked questions about their knowledge of the health risk that was featured in the graphic image. They were asked:

To what extent do you agree or disagree with the following statement – Smoking cigarettes reduces blood flow to the lower limbs.

Fear/disgust is measured by the answer to the question:

Think back to the scenarios that you were shown earlier in this study. In each of the scenarios, there was a warning label about smoking cigarettes. To what extent, if at all, did you feel disgust/fear as a result of the labels?

Possible answers were: “To a great extent”, “Somewhat”, “Very little”, or “Not at all”.

Primary results

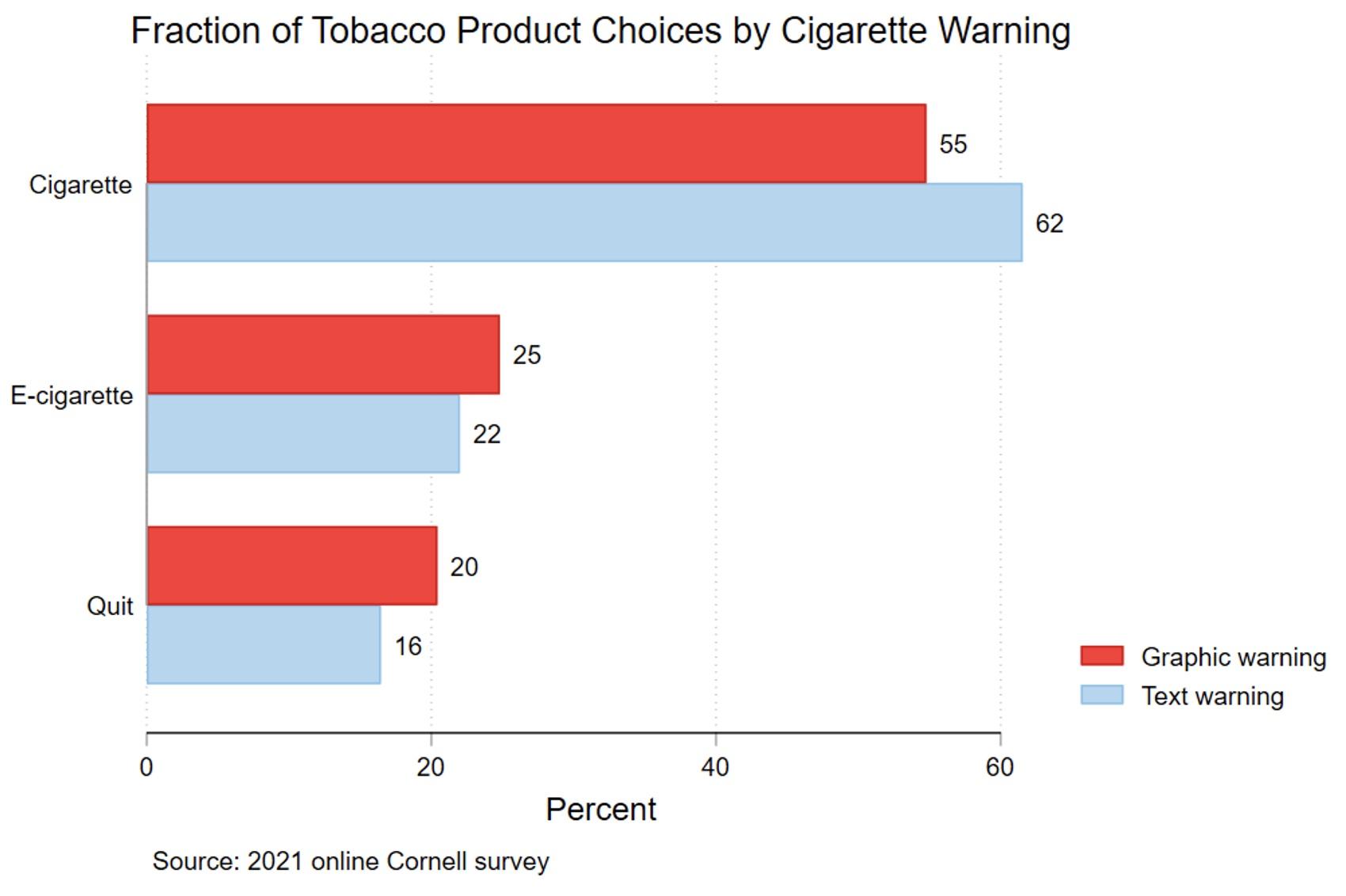

Econometric models were used to estimate the impact of being exposed to the graphic warning label compared with the text warning. Based on these models, we predict the percentage of subjects choosing cigarettes, e-cigarettes, or quitting, by warning label. Figure 2 shows that 62% of subjects shown the text warning chose cigarettes, compared to only 55% of those shown the graphic warning. The movement away from cigarettes due to the graphic warning was distributed between e-cigarettes (3% more than the text-warning group) and quitting (4% more than the text-warning group).

Figure 2 Fraction that chose cigarette/e-cigarette/quitting, by warning type

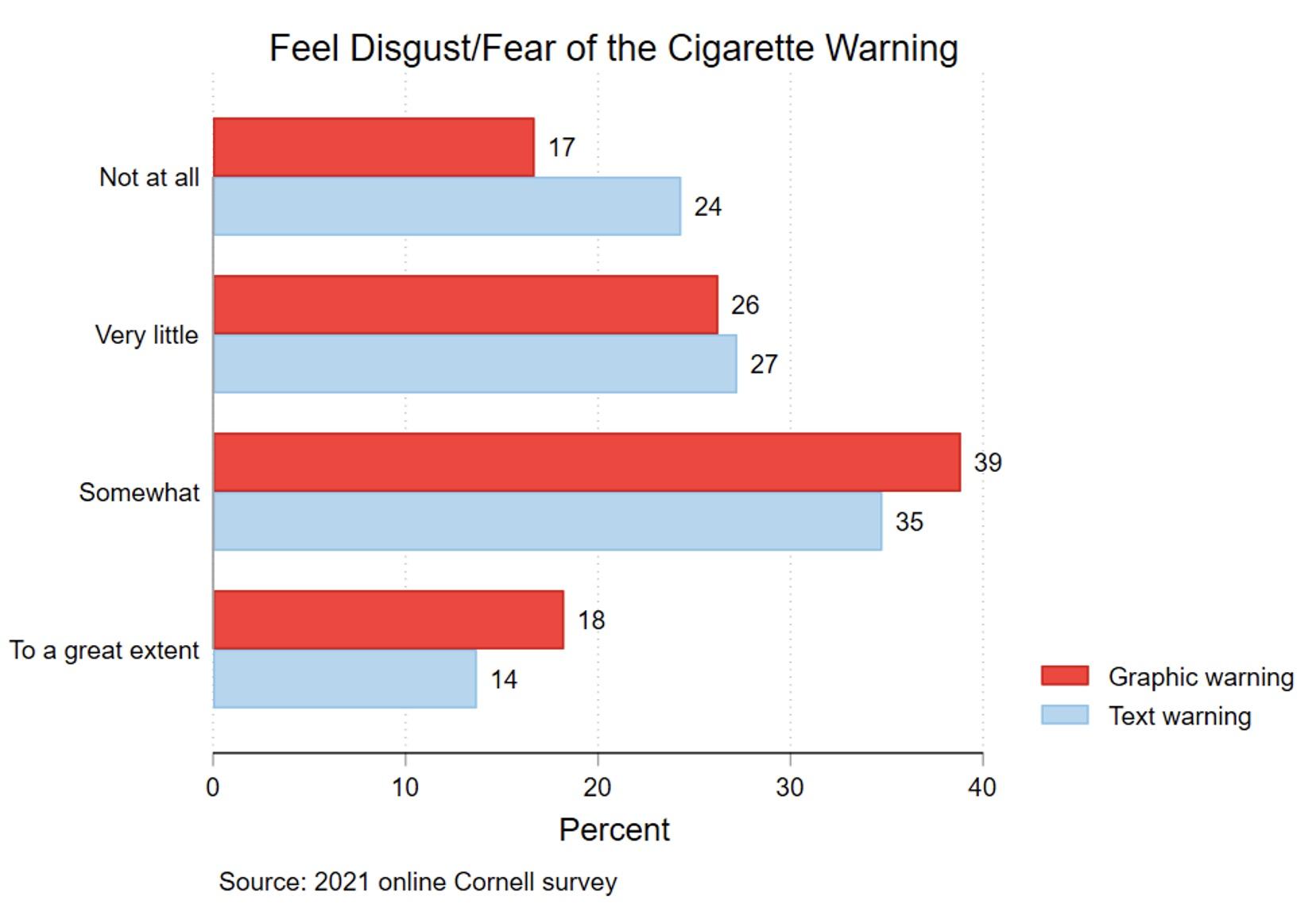

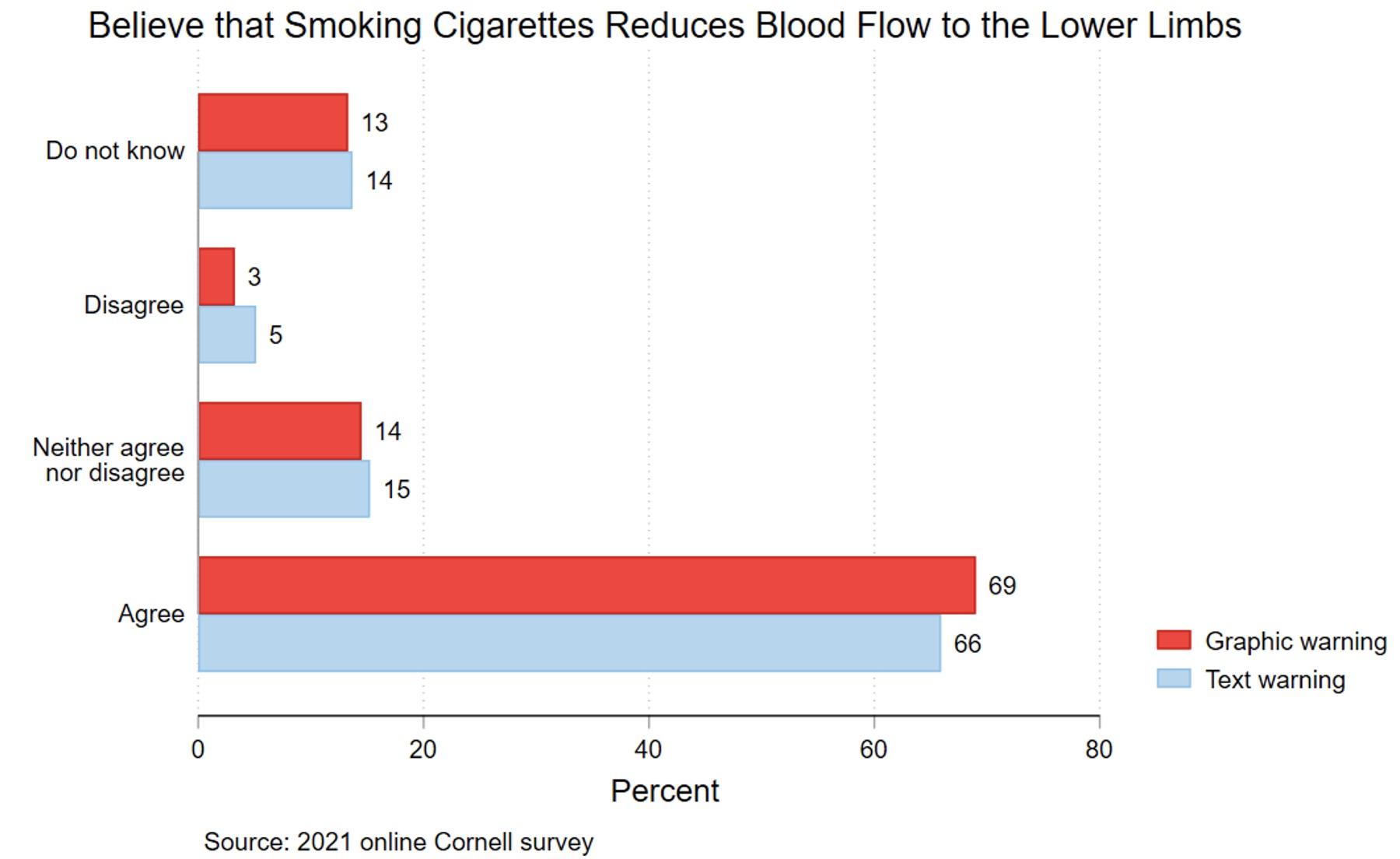

Figures 3 and 4 show that the graphic warning label generated fear/disgust rather than knowledge of the health risk featured in the label. In Figure 3, 24% of the text-warning group reported having no feelings of fear/disgust, compared with 17% of the graphic-warning group. Only 14% of the text-warning group reported they felt fear/disgust to a great extent, compared to 18% for the graphic-warning group. These differences were statistically significant. However, Figure 4 shows limited differences in knowledge of the health risk between the two groups. The relationships between the labels and knowledge were generally not statistically significant.

Figure 3 Feel disgust/fear of the cigarette warning, by warning type

Figure 4 Believe smoking cigarettes reduces blood flow to the lower limbs, by warning type

Policy implications

Our results pose a dilemma for the FDA. Our results suggest that graphic warning labels will work to reduce cigarette use and increase the use of less harmful e-cigarettes and quitting. However, we find that graphic cigarette warnings influence choice largely because they generate fear/disgust rather than change knowledge of the health risk featured in the warning. There are significant First Amendment legal issues that the FDA faces if fear and disgust are the mechanisms through which graphic images operate.

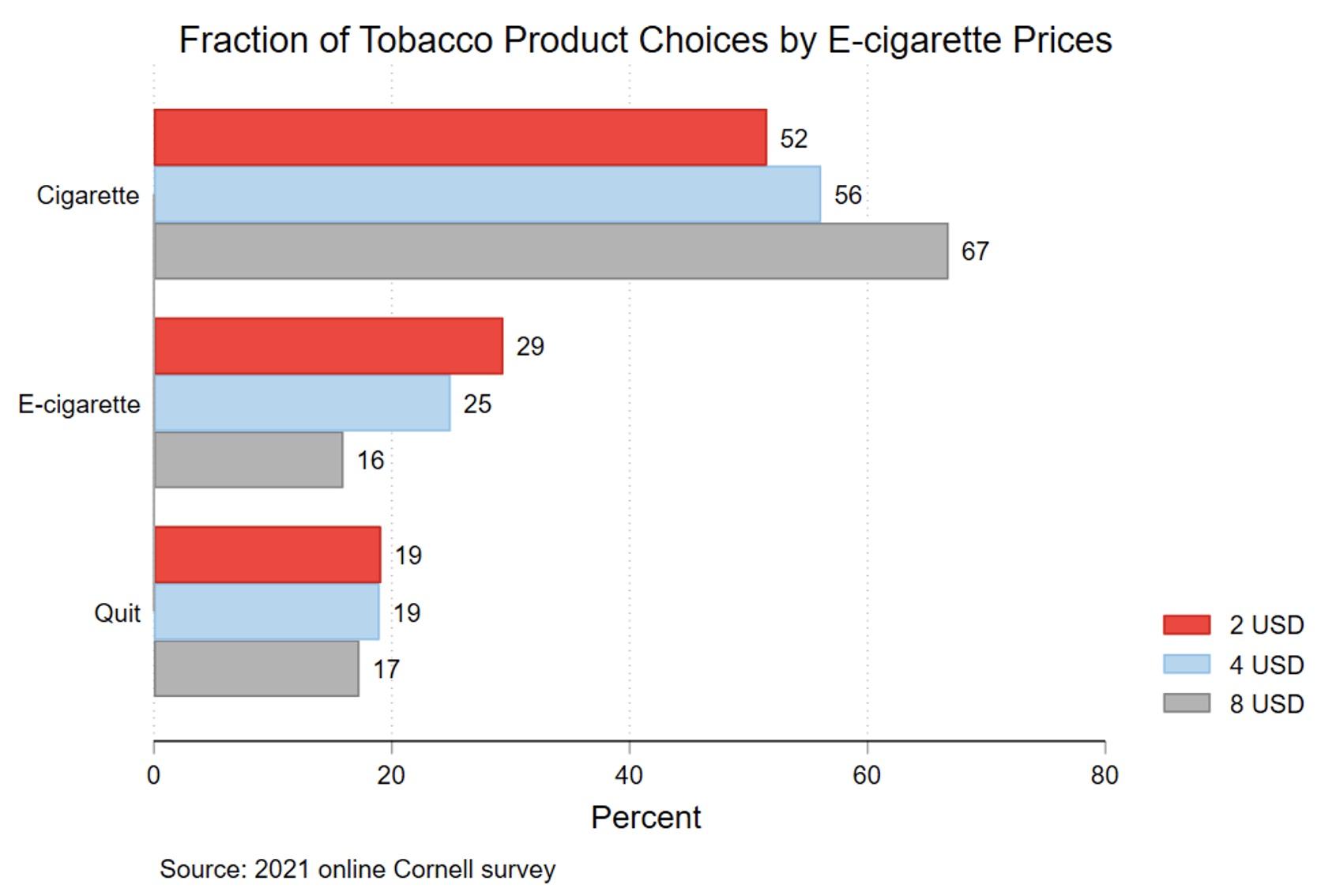

Especially relevant for policy are our findings on the impact of e-cigarette prices on cigarette demand. There is emerging evidence that e-cigarettes and cigarettes are economic substitutes (Pesko et al. 2019). Our results imply that when faced with higher e-cigarette prices, the probability of choosing cigarettes rises significantly (see Figure 5). This suggests that there can be important unintended consequences of taxing e-cigarettes.

Figure 5 Fraction that chose cigarette/e-cigarette/quitting, by e-cigarette prices

Our findings on the availability of e-cigarette flavours also have direct policy relevance. The FDA has consistently denied marketing authorisation to e-cigarettes, except for tobacco-flavoured e-cigarettes. The denials are based on the determination that they are not appropriate for public health, based on the tradeoff between youth taking up vaping and adults quitting smoking. Results from our discrete choice experiment suggest that limiting e-cigarette flavours to only tobacco is likely to increase the probability that adult smokers will choose cigarettes instead of e-cigarettes and does not increase quitting. The FDA is concerned that flavoured e-cigarettes will encourage youth to start using e-cigarettes. While we do not study youth behaviour, we do present the unintended consequences for adult smokers.

Our findings on e-cigarette warnings suggest another possible unintended consequence of current e-cigarette regulatory policies: the current FDA warning on e-cigarettes may decrease the probability of choosing e-cigarettes. This is as intended. However, we estimate that the decrease in the probability of choosing an e-cigarette does not result in a probability of quitting tobacco use; instead, it increases the probability of choosing cigarettes. The unintended consequence is to move tobacco users from less harmful to more harmful products.

Authors’ note: This column was produced with the help of a grant to Cornell University from the Foundation for a Smoke-Free World, Inc. (FSFW), a US nonprofit 501(c) (3) private foundation. This study is, under the terms of the grant agreement with FSFW, editorially independent of FSFW. The FSFW had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The contents, selection, and presentation of facts, as well as any opinions expressed herein are the sole responsibility of the authors and under no circumstances shall be regarded as reflecting the positions of FSFW. FSFW accepts charitable gifts from PMI Global Services Inc. (PMI), which manufactures cigarettes and other tobacco products. Under FSFW’s Bylaws and Pledge Agreement with PMI, FSFW is independent from PMI and the tobacco industry.

References

Federal Register (2019), “Tobacco products; required warnings for cigarette packages, and advertisements (proposed rule)”, Federal Register 84: 42754.

Federal Register (2020), “Tobacco products; required warnings for cigarette packages, and advertisements (final rule)”, Federal Register 85: 15638.

Hammond, D, P W McDonald, R Cameron, and K S Brown (2003), “Impact of the graphic Canadian warning labels on adult smoking behaviour”, Tobacco Control 12: 391–95.

Hammond, D, P W McDonald, G T Fong, K S Brown, and R Cameron (2004), “The impact of cigarette warning labels, and smoke-free bylaws on smoking cessation – evidence from former smokers”, Canadian Journal of Public Health 95(3): 201–4.

Hammond, D, G T Fong, P W McDonald, K S Brown, and R Cameron (2004), “Graphic Canadian cigarette warning labels, and adverse outcomes: Evidence from Canadian smokers”, American Journal of Public Health 94(8): 1442–45.

Hammond, D, G T Fong, R Borland, K M Cummings, A McNeill, and P Driezen (2007), “Text, and graphic warnings on cigarette packages: Findings from the international tobacco control four country study”, American Journal of Preventive Medicine 32(3): 202–9.

Hammond, D (2011), “Health warning messages on tobacco products: a review”, Tobacco Control 20(5): 327–37.

Kenkel, D, A Mathios, G Phillips, R Suryanarahana, H Wang, and S Zeng (2023), “Fear or knowledge? The impact of graphic cigarette warning labels on tobacco product choices”, NBER Working Paper 31534.

Monárrez-Espino, J, B Liu, F Greiner, S Bremberg, and R Galanti (2014), “Systematic review of the effect of pictorial warnings on cigarette packages in smoking”, American Journal of Public Health 104(10): e11–e30.

Noar, S M, M G Hall, D B Francis, K M Ribisl, J K Pepper, and N T Brewer (2016), “Pictorial cigarette pack warnings: a meta-analysis of experimental studies”, Tobacco Control 25(3): 341–54.

Pesko, M, C Maclean, S Adams, B Feng, and R Abouk (2019), “E-cigarette taxation, pre-pregnancy and pre-natal smoking, and birth outcomes”, VoxEU.org, 11 October.

RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company v. US Food and Drug Administration, 696 F3d 1205, 1214 (DC Cir 2012).

RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company; Santa Fe National Tobacco Company, Inc.; ITG Brands, LLC; Liggett Group LLC; Neocom, Inc.; Rangila Enterprises Inc.; Rangila LLC; Sahil Ismail Inc, and Is Like You Inc.; v. US Food and Drug Administration, In the US District Court For the Eastern District of Texas Tyler Division, Case 6:20-cv-10076-JCB (File 4/30/2020).

van Ours, J C, and A Palali (2017), “The impact of tobacco control policies on smoking initiation in Europe”, VoxEU.org, 30 September.

van Ours, J C, and A Palali (2019), “The impact of tobacco control policies on smoking initiation in eleven European countries”, European Journal of Health Economics 20(9): 1287–301.

WHO - World Health Organization (2023), WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2023: Protect people from tobacco smoke, Geneva: World Health Organization.