The Global Crisis of 2007-09 marked a watershed moment in post-war economic history of the world. Prior to it, most financial and economic crises occurred in emerging markets in Asia, Latin America, and elsewhere. While those crises inflicted a great deal of economic and social hardship on the affected economies, the spillover effects of those crises on other economies was by and large limited. What is qualitatively different about the Global Crisis was that it broke out in the US, the world’s largest economy and home to world’s biggest, deepest, and most liquid and sophisticated financial markets. As such, it was bound to have incomparably larger effects on the rest of the world – and so it proved. The Global Crisis was rooted in the US subprime mortgage crisis which, in turn, was rooted in colossal market failures in the country’s housing and financial markets. The crisis paralysed credit flows in the US and spread like wildfire across the Atlantic to Europe, due to the heavy exposure of many European banks to US subprime mortgage assets. The primary channel of crisis transmission to emerging markets was via the reduction of trade and the disruption of capital flows.

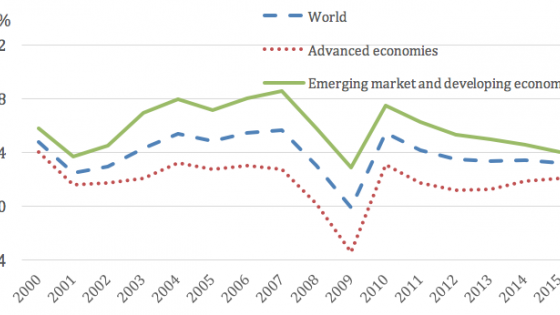

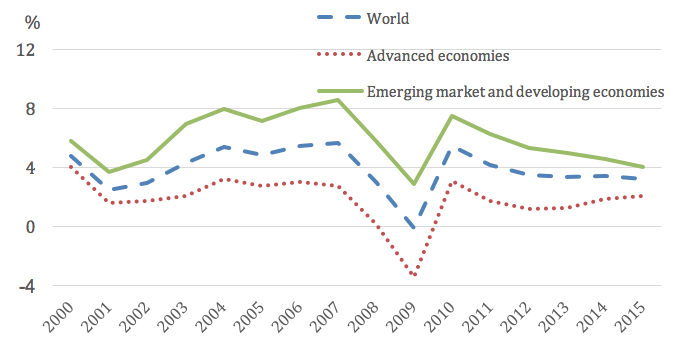

Such a transmission took place for the first and only time in the post-war period (Figure 1). While the decline in global GDP was marginal, the decline in global trade was more substantial (Figure 2). When the Global Crisis broke out, there were genuine, widespread fears of another Great Depression, the interwar catastrophe that devastated the world economy. In fact, only concerted, forceful fiscal and monetary policy interventions by governments and central banks around the world averted another similar occurrence.

Figure 1 GDP growth of advanced economies, emerging market and developing economies, and the world, 2000-2015

Source: IMF, World Economic Outlook database October 2016.

Figure 2 Global trade growth

Source: IMF, World Economic Outlook database October 2016

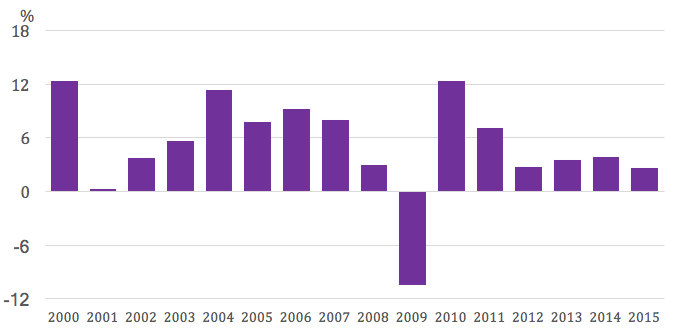

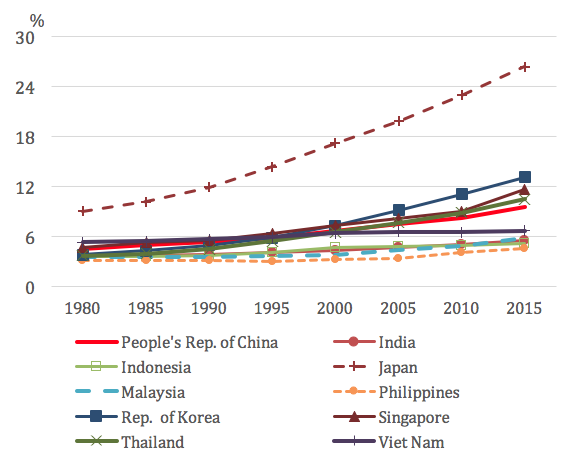

There is a visible slowdown of global growth momentum since the Global Crisis. In other words, the effects of the crisis continue to reverberate. Initially, the slowdown was more evident in the advanced economies, giving rise to the notion of a two-speed global economy of fast-growing emerging markets and slow-growing advanced economies. However, in more recent years, the growth deceleration has spread to emerging markets, causing the world economy as a whole to slow down. The effect of the Global Crisis on global growth is thus significant and persistent. In addition, a number of structural factors also contributed to the weakening of the world economy since 2008. For example, China’s growth has moderated in recent years, largely due to structural factors such as population aging, convergence toward high income, and rebalancing toward domestic demand. Above all, population aging is not confined to China but poses an increasingly global headwind against growth. Whereas the demographic transition toward older population structures was almost exclusively a rich-country trend, in recent decades it has spread to developing countries, including much of Asia (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Demographic transition

Source: United Nations (2015).

While it is admittedly too early to tell whether the Global Crisis will permanently lower the global growth trajectory, it has so far been a game changer that has had a profound effect on the global economic and financial landscape. A key question is whether vulnerability and adjustment to shocks has changed in fundamental ways since the crisis. While this question is relevant for all countries, it is perhaps especially relevant for middle-income countries, in light of their growing integration into the world economy. For example, whereas much of the foreign capital which flows into low income countries is foreign aid and foreign direct investment (FDI) in natural resource industries, middle-income countries receive greater amounts of potentially volatile short-term capital inflows, rendering them more vulnerable to shocks. Furthermore, the policy tools and institutions for coping with shocks tend to be less developed in middle-income countries than in high income countries. Of particular interest is the volatility and level of growth.

The interest in these questions follows the quest for understanding the flexibility of adjustment, a research agenda that was propagated by a seminal paper by Rodrik (1999), who identified weak institutions and latent social conflict as the main reason for the negative impact of volatility on growth.1 Against this background, in a new paper we aim to uncover how countries cope with crises and shocks (Aizenman et al. 2017). We approach the subject by looking at whether better coping mechanisms are associated, on average, with lower volatility of GDP growth, and higher average growth rates. Specifically, we ask:

- What are the conditions that enhance a faster and smoother adjustment of growth to shocks, especially for middle-income countries, before and after a crisis?

- Is faster and smoother adjustment to shocks associated with higher average growth rates and/or lower output volatility, before and after a crisis?

Our analysis does two things. First, it studies the natural patterns of growth and volatility adjustment to shocks in the window of the corresponding shock, focusing on the difference between pre-2008 and the post-2008 periods, comparing middle-income countries and other income groups. Second, it estimates GDP growth and volatility adjustment – i.e. dependent variables – on a set of domestic and external macroeconomic shocks, and then maps the estimates and residuals from the growth and volatility estimation to country's institutions and fundamentals.

Summary and concluding observations

Flexibility of growth adjustment is an issue of high and growing importance, especially against the background of the post-crisis global growth slowdown and heightened political and policy uncertainty. The vulnerability of middle-income countries to shocks is an interesting issue, since these countries are typically more integrated into the world economy but, unlike most high-income countries, often lack well-established policies and institutions to cope with shocks.

Our analysis examines and compares the role of institutions and fundamentals on the adjustment of growth and volatility to shocks in the pre-crisis and post-crisis periods. Empirical analysis of panel data of high-income, middle-income, and low-income countries over 2004-2014 shows that the associations of growth, volatility, shocks, institutions, and economic fundamentals have changed in important ways after the crisis. More specifically, we find that GDP growth across all income groups of countries have become more dependent on the external factors, including global growth, global oil prices, and global financial volatility. In addition, despite the slowdown of global trade after the crisis, there is evidence that growth spillovers from trade partners have economically significant effects on a country's growth. There is nothing unique about the exposure of middle-income countries to such global shocks.

A country’s response and adjustment to shocks depends on several factors – including the age-dependency ratio and foreign reserves, to name just two. After accounting for the effects from global shocks, for middle-income countries we identify some factors that facilitate adjustment to shocks, in terms of growth and volatility. Higher education attainment, higher manufacturing output in GDP, and higher exchange rate stability increase economic growth. Lower political polarisation, higher exchange rate flexibility, and higher education attainment reduce the volatility of economic growth.

Therefore, overall, our cross-country findings suggest that countries can cope with shocks better in the short to medium term by appropriately using flexible policy tools – such as greater exchange rate flexibility help reduce growth volatility – as well as maintaining solid long-term fundamentals. For instance, higher education and lower political polarisation both help reduce growth volatility.

Authors’ note: Donghyun Park provided overall guidance for the paper on which this column is based. Ilkin Huseynov provided able assistance with the data. Akiko Terada-Hagiwara and participants at the ADB workshop on “Transcending the Middle-Income Challenge” provided useful comments and suggestions. Financial support from the ADB is gratefully acknowledged. Any errors are ours.

References

Acemoglu, D, S Johnson, J A Robinson, and Y Thaicharoen (2003), “Institutional Causes, Macroeconomic Symptoms: Volatility, Crises and Growth”, Journal of Monetary Economics 50 (1), 49-123.

Aghion, P, P Bacchetta, R Rancier, K Rogoff (2009), “Exchange rate volatility productivity growth: The role of financial development”, Journal of Monetary Economics 56, 494–513.

Aizenman, A, Y Jinjarak, G Estrada and S Tian (2017), "Flexibility of Adjustment to Shocks: Economic Growth and Volatility of Middle-Income Countries Before and After the Global Financial Crisis of 2008", NBER Working Paper No. 23467

Beck, T, G Clarke, A Groff, P Keefer, and P Walsh (2001), "New tools in comparative political economy: The Database of Political Institutions", World Bank Economic Review , 15 (1), 165-176 .

Broda, C (2004), "Terms of Trade and Exchange Rate Regimes in Developing Countries", Journal of International Economics, 63 (1), 31-58.

Céspedes, L F, and A Velasco (2012),"Macroeconomic Performance During Commodity Price Booms and Busts", IMF Economic Review 60 (4), 570-599.

Easterly, W, R Islam, and J E Stiglitz (2000), “Shaken and Stirred: Explaining Growth Volatility” In B Pleskovic and J E Stiglitz (eds.), Annual World Bank Conference on Development Economics 2000, Washington, D.C.: World Bank.

Edwards, S, and E Levi-Yeyati (2005), “Flexible Exchange Rates as Shock Absorbers”, European Economic Review, 49 (8), 2079-05.

Frankel, J A (2011), "A Solution to Fiscal Procyclicality: the Structural Budget Institutions Pioneered by Chile", Journal Economía Chilena (The Chilean Economy), 2: 39-78.

Frankel, J A, C A Vegh, and G Vuletin (2013), "On graduation from fiscal procyclicality", Journal of Development Economics, 100, 32-47.

Gavin, M, R Hausmann, R Perotti and E Talvi (1996), Managing Fiscal Policy in Latin America and the Caribbean: Volatility, Procyclicality, and Creditworthiness, Inter-American Development Bank, Office of the Chief Economist, Working Paper 326.

Hausmann, R, and M Gavin (1996), "Securing Stability and Growth in a Shock Prone Region: The Policy Challenge for Latin America", IDB Working Paper No. 315.

Inter-American Development Bank (1995), Overcoming Volatility: Economic and Social Progress in Latin America 1995, Washington, D.C.: Inter-American Development Bank.

Rodrik, D (1999), “Where Did All the Growth Go? External Shocks, Social Conflict and Growth Collapses”, Journal of Economic Growth 4 (4), 385-412.

United Nations (2015). World Population Prospects: The 2015 Revision, DVD Edition, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division.

Endnotes

[1] Follow up research includes Easterly et al. (2000), which honed in on the financial system as the primary factor in growth volatility. They found that up to a point, greater financial depth is associated with lower growth volatility. But as financial depth and leverage grow, the financial sector could become a source of macroeconomic vulnerability. Aghion et al. (2009) offered empirical evidence that real exchange rate volatility can have a significant impact on the long-term rate of productivity growth, but the effect depends critically on a country’s level of financial development. Acemoglu et al. (2003) took the primacy of institutions a step further, arguing that crises are caused by bad macroeconomic policies, which increase volatility and lower growth. IDB (1995) and Hausmann and Gavin (1996) found that higher volatility was associated with both lower growth and higher inequality, with the latter tending to be highly persistent.

The follow up literature provided ample evidence that, for developing and emerging market countries, less flexible exchange rate regimes are associated with slower growth, as well as with greater output volatility (Broda 2004, Edwards and Levy-Yeyati 2005). In a related study by the IDB, Gavin et al. (1996) identified the pro-cyclicality of fiscal policy as a major amplifier of developing countries’ vulnerability to shocks. Remarkably, over the last two decades the fiscal policies of about a third of developing countries have become counter-cyclical (see Frankel 2011 and Frankel et al. 2013).

[SH1]I think there was supposed to be a reference to author’s research here, which looks like it was cut and pasted out.