The energy transition is slow. In 2021, on average 82% of global primary energy came from fossil fuels (coal, oil and natural gas) (BP 2022). Although coal use is in decline, oil and natural gas use continues to grow at historic rates. Since natural gas may play a large role in the energy transition, methane leakages must be tightly controlled. It is therefore imperative that forward-looking policy focuses on the oil and gas industry.

After measuring oil and gas common volatility (a broad measure of the magnitude of geopolitical events) for a wide range of oil and gas equities, countries, and regions of the world, our research identifies the extent to which common volatility shocks to the industry are driven by climate change news (Campos-Martins and Hendry 2023).

Events shaking the oil and gas industry

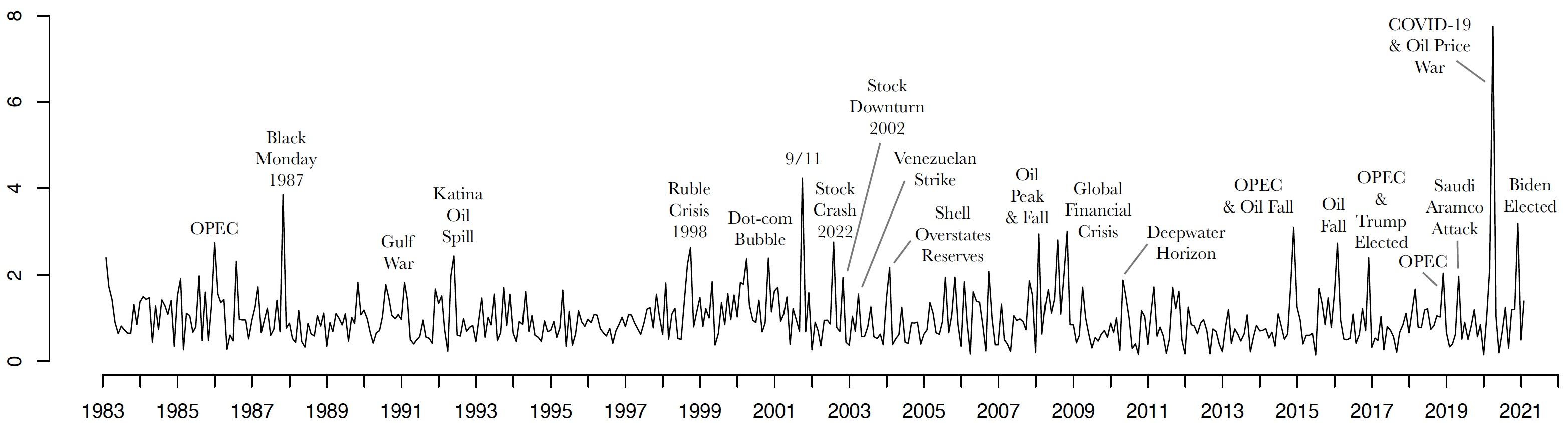

Since 1983, there have been a number of geopolitical events which caused oil and gas equity prices to move at the same time, having a major impact on the industry. Figure 1 shows how oil prices have responded to major events, with extreme volatility peaks during Black Monday in 1987, the 2007-09 Great Recession, after the 9/11 terrorist attacks, and most recently the COVID-19 pandemic.

Oil and gas loadings seek to measure how much an asset’s volatility is affected by common factors, particularly geopolitical events in the oil and gas industry. It is not surprising that some supermajors, including Shell, BP, Chevron, and ConocoPhillips, have the largest exposure to these shocks. However, oil and gas companies tend to have different exposures to global shocks. Companies operating in markets or countries with more stringent climate policies are more exposed to climate transition risk. Investors must price carbon transition risk to compensate for their exposure (Bolton and Kacperczyk 2021). Research by Engle and Campos-Martins (2023) examines portfolio optimality, which can be used to determine how investors in oil and gas companies can reduce their exposure to broad geopolitical risk.

Figure 1 The monthly averaged oil and gas global common variance index

Note: OPEC indicates an announcement and Peak or Fall indicate oil price peak or fall, respectively.

Text-based proxies of climate concerns and news

Events with large impacts shaking the oil and gas industry come from different sources, including geopolitical. The ‘price war’ between Saudi Arabia and Russia in the first quarter of 2020 rapidly spilled over to the global stock market, confirming tail risks can have major implications for the global economy. We use a text-based proxy – the Media Climate Change Concerns (MCCC) index of Ardia et al. (2020) – to determine whether climate concerns and news are potential drivers of volatility shocks to the oil and gas industry. Additionally, we use two monthly climate change news indices proposed by Engle et al. (2020) to differentiate between effects of positive and negative news, thus reflecting climate sentiment.

Our results provide a systematic assessment of climate-driven oil and gas industry global risks, consistent over time, as perceived by the press, the public, global investors, and policymakers. However, not all geoclimatic shocks are alike. Climate change risk is more of a concern to oil and gas investors when there is turmoil in the US energy market. While Russia’s invasion of Ukraine resulted in record high oil prices, oil and gas dividends and share buybacks created incentives to hold oil and gas companies’ shares despite EU countries ramping up investment in renewables and increasing energy efficiency and security.

What do we find?

There are two types of climate risk drivers: physical and transition. Physical risk concerns how climate change can adversely impact capital stock, economic activities, and markets directly as extreme climate disasters become more frequent. Transition risk includes exposure to sudden changes in carbon pricing policy, legislation (such as the UK’s 2008 Climate Change Act), new clean-energy technology, and market sentiment. We find systemic implications of climate change for financial markets are most likely to come from exposure to transition risk, especially disorderly transition.

News with explicit mentions of the fossil fuel industry and carbon pricing, or of carbon and technological disruption, drive global oil and gas variance shocks. To date, legal actions and liability or litigation risk seem to have no impact. Setzer and Higham (2021) show that most cases of climate change litigation filed before courts have been brought against governments for their support for the fossil fuel industry. However, societal impact relating to the consequences of climate action failure seems to affect the oil and gas industry, possibly by altering investors’ taste for climate change, interpreted as market sentiment risk drivers, creating pressure on the industry.

Negative climate change news amplifies the effects of oil (variance) shocks as it increases uncertainty about the viability of investments in carbon-intensive assets and activities in a low-carbon economy. For example, the Deepwater Horizon disaster in 2010 had an impact on oil markets at the same time as concerns about its environmental impact, possibly increasing uncertainty about the future viability of the oil and gas industry.

When no cross-sectional or cross-country information is used in the analysis, only oil shocks explain extreme returns to energy equity prices unlike for the oil and gas global common variance, reinforcing both how a common climate policy can be important and why negotiations during climate summits can disrupt global markets. Investors appear to be pricing climate change risks in oil and gas stocks rather than in the commodities, possibly reflecting short-term optimism about oil and gas versus the long-term nature of climate change.

An alternative explanation may be consumers’ misperception of the carbon footprints of oil producers. Major oil and gas producers have committed to reduce their (relatively small) scope 1 (direct) and 2 (indirect from the consumption of purchased energy) emissions. These two categories are targeted because oil and gas companies have a limited ability to reduce their scope 3 emissions (indirect emissions related to products purchased and sold). Presently, oil has a low elasticity of demand as consumers are unable to substitute fossil fuels easily when prices increase, but that will change as electric cars replace gasoline-driven ones.

Combined, these results suggest that the effects of climate change concerns on financial markets are more intricate and systemic than expected. The signs and magnitudes of impacts differ across climate risk drivers. Physical risk appears to be heavily discounted by investors because of its long-term nature, whereas transition risk tends to materialize in a shorter horizon. When accounting for climate sentiment, global turmoil seems to materialise only when climate news is negative and worldwide. Moreover, the adverse effect is amplified by oil price movements but weakened by stock market shocks.

Conclusion

Governments and companies need to assess their climate pledges and rethink the way they publicize or politicise them. The announcement of infeasible net-zero goals or carbon prices that are too low or ineffective, may not (only) damage a firm’s or country’s competitiveness individually, but may (also) disrupt global markets. The stability and resilience of the financial system will be crucial in managing climate-related transition risks and as well as regulation (Hengge et al. 2023) in mobilising capital for low-risk green investments.

References

Ardia, D, K Bluteau, K Boudt, and K Inghelbrecht (2020), “Climate change concerns and the performance of green versus brown stocks”, National Bank of Belgium Working Paper 395.

Bolton, P and M Kacperczyk (2021), “Global Pricing of Carbon-Transition Risk”, VoxEU.org, 24 March.

BP (2022), Statistical review of world energy, 71st edition.

Campos-Martins, S and D F Hendry (2023), “Common volatility shocks driven by the global carbon transition”, Journal of Econometrics, 105472.

Engle, R F and S Campos-Martins (2023), “What are the events that shake our world? Measuring and hedging global COVOL,” Journal of Financial Economics 147: 221–242.

Engle, R F, S Giglio, H Lee, B T Kelly, and J Stroebel (2020), “Hedging climate change news,” The Review of Financial Studies 33: 1184–1216.

Hengge, M, U Panizza and R Varghese (2023), “Carbon policies and stock returns: Signals from financial markets”, VoxEU.org, 6 June.

Setzer, J and C Higham (2021), “Global trends in climate change litigation: 2021 snap-shot”, Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment and Centre for Climate Change Economics and Policy, LSE.