The economic sanctions that the US and the EU have imposed as response to Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine have transformed the Russian oligarchical model to resemble the close-knit family-run business holdings present for many decades in East Asia (Berner et al 2022, Ongena et al 2022, Evenett and Pisani 2022, Mahlstein et al. 2022, Claessens et al 2000). Trust between politicians and entrepreneurs in Russian society is so low that politicians rely on their kin to accumulate wealth from transacting with the government (Bosio et al 2022). This inbreeding leads to a concentrated elite, where politics and business become one.

The emergence of politically connected family-run businesses leads to a reduction in innovation, lowered productivity and ultimately a stagnant economy (Faccio 2006). It leaves open, however, the question of which parts of society have an interest in increased political and property rights in Russia. The encapsulation of power reduces the possibility of evolutionary reform (Olson 1982), although the increases in income inequality that are apparent since sanctions began may bring about discontent and broad-based demand for social change.

The evolution of the Russian oligarchs

The transition to a post-communist economy in Russia involved rapid privatisation of vast state assets, often falling in the hands of few well-positioned individuals who became known as oligarchs for their massive wealth and political influence (Treisman and Shleifer 2004, Aslund 1995). The initial group of oligarchs emerged in the mid-1990s from within the ranks of academia or the management of state-owned enterprises, and famously assisted President Yeltsin in securing his second term in power (Guriev and Rachinsky 2005).

With the ascend of Vladimir Putin in the Kremlin their influence dissipated, as some were imprisoned while others emigrated or sold off their assets. A second wave of oligarchs emerged in the 2000s – friends and former colleagues of President Putin either from his years in the St Petersburg municipal administration or his Dresden tenure in the KGB (Aslund 2019). These oligarchs worked in close cooperaton with the government, displacing a system of crony capitalism with a system of state capitalism whereby the new oligarchs benefited from financing by state-owned banks and access to public procurement projects (Djankov 2015).

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has created a third wave of oligarchs, in even closer proximity to the top of the political establishment. The reason for this tighter relation between political and business elites is two-fold. First, sectoral economic sanctions as well as sanctions on Russia’s banking industry have made it difficult for private enterprise to operate normally, absent state support. Second, the threat of continued or new sanctions made many entrepreneurs choose to distance themselves from President Putin and his war effort.

Who are the new oligarchs?

In the year since the war in Ukraine started, two dozen business people with family connections to top politicians have joined the oligarchy. These include President Putin’s younger daughter, who through her investment fund has been the recipient of numerous large contracts from state-owned energy companies (Bloomberg 2022). Her former husband runs the largest Russian petrochemicals company, Sibur, as well as his own investment fund (The Guardian 2022). The two closest friends of President Putin’s daughter have become billionaires by investing in Russian technology and agri-processing companies, while receiving state subsidies for their R&D activities (Hyatt 2022).

Other oligarchs have sprung up within the families of President Putin’s lieutenants. The son-in-law of Foreign Minister Lavrov runs an investment fund with assets exceeding $6 billion (Varvitsioti et al 2022). The son-in-law of Viktor Medvedchuk, President Putin’s former closest ally in Ukraine, runs another investment fund with large agricultural holdings which have become recipients of state subsidies for import substitution (Rouhandeh 2022). The son of a former Prime Minister and head of the Russian foreign intelligence service, the son of the former head of the presidential administration and the son of the current head of the Russian Security Council have all joined the ranks of the oligarchs (Taylor and Bove 2022).

This list can be extended with the scions of former and current ministers, heads of security and intelligence committees and regional governors. Altogether, two dozen oligarchs related by family ties to top Russian politicians have become prominent members of Russia’s business elite (Treisman 2022).

Implications

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has created a new dynamic, whereby economic power has been concentrating in the hands of few families at the apex of political power. The new class of oligarchs owe their riches to the sway of their parents, who use their political connections to transfer state resources – through subsidy schemes and public procurement contracts – to the business holdings of their children.

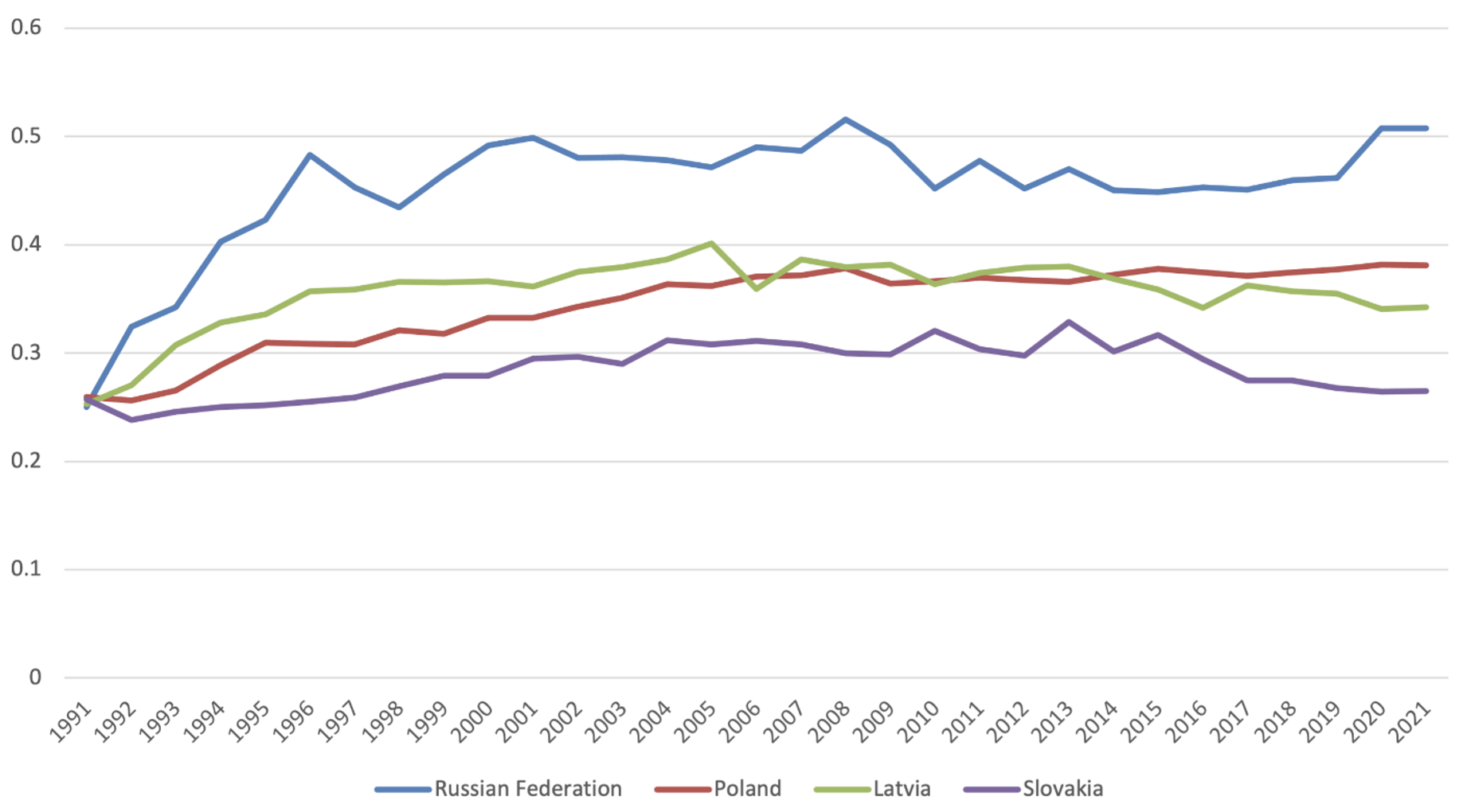

The largest effect of the imposition of sanctions, however, is increased income inequality in Russia (Figure 1). Inequality shot up at the start of economic reforms in the early 1990s but was falling steadily after the financial crisis of 2008. Inequality started rising again with the initiation of sanctions after the Crimea annexation in 2014 (a large slew of sanctions took place in 2018) and will likely rise even further with the new waves of sanctions. The comparison with other post-communist economies is striking. Starting at similar levels of inequality in 1991, Slovakia has managed to bring inequality back to its initial level at the start of transition, while Latvia and Poland have managed to curb further rises in the past dozen years. In contrast, inequality in Russia is nearing its highest point since the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

Figure 1 Pre-tax national income top 10% share trend, 1991-2021

Such concentration of economic power is shown to retard innovation and economic growth (Claessens et al. 2002, Piketty and Saez 2003). Inequality in income is associated with inequality of opportunity. When those at the bottom of the income distribution are at great risk of not living up to their potential, the economy pays a price not only with weaker demand today, but also with lower growth in the future (Corak 2013). Societies with greater inequality are less likely to make public investments which enhance productivity, such as in public transportation, infrastructure, technology, and education (Berg and Ostry 2017). Russia is heading precisely in this direction.

References

Aslund, A (1995), How Russia Became a Market Economy, Brookings Institution Press.

Aslund, A (2019), Putin’s Economic Policy and Its Consequences, Oxford University Press.

Berg, A and J Ostry (2017), “Inequality and Unsustainable Growth: Two Sides of the Same Coin?”, IMF Economic Review 65(4): 792–815.

Berner, R, S Cecchetti and K Schoenholtz (2022), “Russian Sanctions: Some Questions and Answers”, VoxEU.org, 21 March.

Bloomberg (2022), “Putin’s daughter has a big new job at Russia’s most powerful business lobby,” 14 July.

Bosio, E., S. Djankov, E. Glaeser and A. Shleifer (2022), “Public Procurement in Law and Practice”, American Economic Review 112(4): 1091-1117.

Claessens, S, S Djankov and L Lang (2000), “The separation of ownership and control in East Asian Corporations”, Journal of Financial Economics 58(1–2): 81-112.

Claessens, S, S Djankov, J Fan and L Lang (2002), “Disentangling the Incentive and Entrenchment Effects of Large Shareholdings”, The Journal of Finance 57(6): 2741–71.

Corak, M (2013), “Income Inequality, Equality of Opportunity, and Intergenerational Mobility,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 27(3): 79-102.

Djankov, S (2015), “Russia’s Economy under Putin: From Crony Capitalism to State Capitalism,” PIIE Policy Brief 15-18.

Evenett, S and N Pisani (2022), ”Less than Nine Percent of Western Firms Have Divested from Russia,” Economics Department, University of St. Gallen, 20 December.

Faccio, M (2006), “Politically Connected Firms”, American Economic Review 96(1): 369-386.

Guriev, S and A Rachinsky (2005), “The role of oligarchs in Russian capitalism”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 19(1): 131–150.

Hoffman, D (2002), The Oligarchs: Wealth and Power in the New Russia, Perseus Book Group.

Hyatt, J (2022), “How Putin Used Russia’s Sovereign Wealth Fund to Create A ‘State-Sponsored Oligarchy’”, Forbes, 8 March.

Mahlstein, K, C McDaniel, S Schropp, and M Tsigas (2022), “Potential economic effects of sanctions on Russia: An Allied trade embargo”, VoxEU.org, 6 May.

Olson, M (1982), The rise and decline of nations, Yale University Press.

Ongena, S, A Pestova and M Mamonov (2022), “The price of war: Macroeconomic effects of the 2022 sanctions on Russia”, VoxEU.org, 15 April.

Piketty, T and E Saez (2003), “Income Inequality in the United States, 1913-1998,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 118(1):1-39.

Rouhandeh, A (2022), “If Putin Picks Puppet Ukraine Leader, Viktor Medvedchuk is Odds-on Favorite,” Newsweek, 24 February.

Taylor, A and T Bove (2022), “Meet the Russian billionaires and elites getting hit with sanctions in escalating Ukraine conflict,” Fortune, 23 February.

The Guardian (2022), “Russia: the oligarchs and business figures on western sanction lists,” 10 March.

Treisman, D and A Shleifer (2004), “A Normal Country”, Foreign Affairs 83(2): 20-38.

Treisman, D (2022), “What Could Bring Putin Down?” Foreign Affairs, 2 November.

Varvitsioti, E, H Foy and V Pop (2022), “EU set to add 14 more Russian business chiefs to its sanctions list”, Financial Times, 9 March.