During the rapid spread of COVID-19 in Japan, the Japanese government decided to provide a Special Cash Payment (SCP) of 100,000 yen per person to all residents as a part of the “Emergency Economic Measures to Cope with COVID-19”. A similar type of cash transfer programme was conducted in many countries, and many papers have already studied the impacts of such transfers (Andersen et al. 2020, Bounie et al. 2020, Baker et al. 2020, Coinbion et al 2020, Chronopoulos et al. 2020). These studies demonstrate that evaluating the impacts of cash transfers is difficult under the COVID-19 pandemic. Most countries where large cash transfers were distributed experienced strict lockdowns and are suffering from large income shocks due to high unemployment rates, so responses to a cash transfer were different from those under the pre-pandemic situation. Some services, such as restaurants or travel, were prohibited and people chose to stay at home rather than to keep working and spending. In response to this situation, labour supply and saving behaviour as well as consumption were affected by the cash transfers.

In a recent paper (Hattori et al. 2021), we focus on estimating the marginal propensity to consume (MPC) out of the SCP to assess the cash transfer policy. Unlike in other countries, the evaluation of impacts of the cash transfer in Japan is simpler and more straightforward since households in Japan were much less affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. There were no strict lockdowns, almost all shops and stores kept operating (at least when the cash transfer was distributed), and the unemployment rate remained relatively low. Accordingly, just like a stimulus policy during a normal recession, understanding how much households spend out of the SCP would be the most important part of the impacts.

In our analysis, we use publicly available data from the Family Income and Expenditure Survey (FIES). FIES is a national representative monthly survey and various cross-tabulated results are published and available online.1 It is becoming popular to use alternative data that are collected by private companies such as credit cards, bank accounts, and private finance management (PFM) apps. In fact, many previous studies used this type of data for examining the impacts of COVID-19 (Andersen et al. 2020, Baker et al. 2020, Bounie et al. 2020, Chronopoulos et al. 2020). As for the Japanese case, Kubota et al. (2020) use bank account data and Kaneda et al. (2021) use PFM app data. Although alternative data allow researchers to conduct real-time analysis, there are still some advantages to using traditional official statistics. Alternative data are not nationally representative, and therefore we should be careful in drawing macroeconomic implications. With official data, we can use detailed and comprehensive categorisations of expenditure, which is rarely available with alternative data. In addition, the results of analysis using publicly available data are easy to reproduce, and are therefore preferable from a transparency perspective (e.g., Miguel 2021).

To estimate the MPC, we exploit the differences in timing in the transfer payments. While the SCP was paid based on applications by eligible households, the applications were not accepted simultaneously. The administrative process for the SCP was managed by local governments, and each municipality set a different date for accepting applications. Moreover, as the date depends on administrative capacity, the difference in the timing can be treated as exogenous for each household. By exploiting the difference in timing, therefore, we can identify the causal effects of the SCP.

To illustrate how we can estimate the MPC, we compare the SCP received and consumption dynamics in two groups of municipalities: those that started distributing the SCP earlier (cities that started accepting applications before 25 May) and those that did so later. Figure 1 shows the amount of the SCP received in each group of cities. While the SCP is recorded as “Special Income” in FIES, in which some other sources of income are included, the income measure appropriately captures the timing and amount of the SCP received. Since the mean number of household members is around 2.8, the mean total SCP should be around 280,000 yen, and the first SCP was paid in late May in the earliest municipality. Thanks to this difference in timing of payment, we can conduct a difference-in-differences estimation.

Figure 1 The SCP payments: “Special Income” in FIES

Source: Authors’ calculation based on Family Income and Expenditure Survey

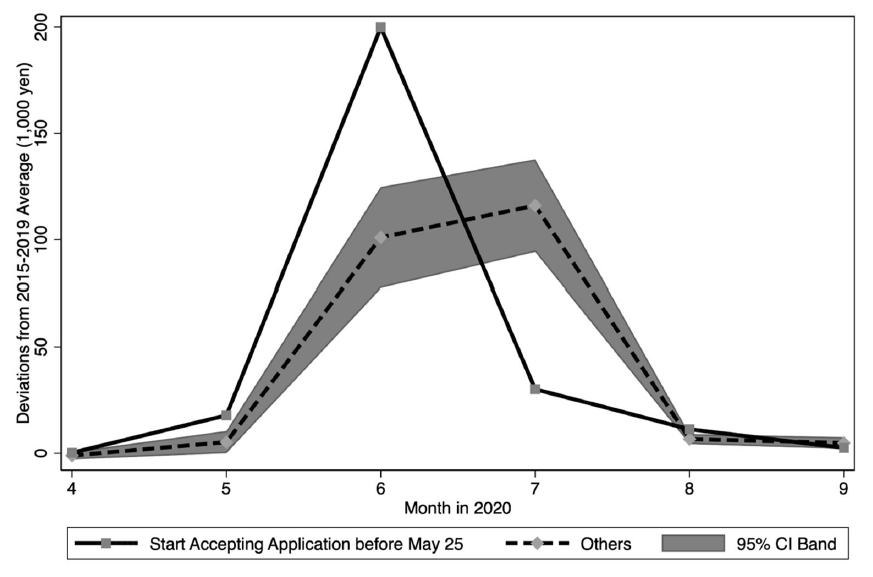

Figure 2 illustrates consumption trends in both groups in 2020, expressed as deviations from the average between 2015–2019. According to the figure, consumption was much lower than usual in April and May nationwide, but it returned to normal afterwards. As for the impact of the SCP, consumption in the earlier group surpassed that of the other group in June. Consumption in the other group was low in June and July, but it exceeded that of the earlier group in August. These results suggest that the SCP increases household consumption.

From this comparison, we can get a rough estimate of the MPC as follows. In June, the earlier group received 200,000 yen on average (more than the average from 2015-2019) as Special Income, whereas others received 100,000 yen. The difference in the SCP received between two groups was 100,000 yen. The difference in household consumption between the two groups in June is 9,000 yen, which means the MPC – i.e. the ratio of the two – is 9%. We also conducted a regression analysis to confirm that a similar level of the MPC (from 7.6% to 11.2% depending on the specifications) can be obtained from the procedure.

Figure 2 Application acceptance date and consumption

Source: Authors’ calculation based on Family Income and Expenditure Survey

This estimated MPC is comparable in magnitude to the estimates in previous studies examining stimulus policies in non-pandemic periods in Japan. For example, Hsieh et al. (2010) focus on the “Shopping Coupon Program” in 1999, finding the MPC between 10% and 20%. The Cabinet Office (2012) studies the “Cash Payments” in 2009, reporting an estimated MPC of 8% in the month of receipt. This similarity suggests that the impacts of the SCP on household consumption did not differ from those during the non-pandemic period. According to these results, the aggregate consumption was increased by 1.32 trillion yen since the total amount of the SCP is approximately 12 trillion yen.

This non-negligible increase in aggregate consumption may have caused the spread of infection. To explore this possibility, we also examine the consumption response by categories based on the infection risk. Specifically, we define the four subcategories: spending on “face-to-face services,” such as traveling and eating out, which carry a relatively higher risk; spending on “goods/services purchased at home,” such as utilities and internet services (including subscriptions to Netflix or Zoom), having the lowest risk; spending on “transfer payments,” including gifts and remittances; and spending on other “goods/services purchased at stores.” As we find that most of the consumption responses are attributed to “goods/services purchased at stores,” we do not find a statistically significant change in “face-to-face service” consumption. Since Tomura (2021) shows that most of infection associated with consumption activities comes from “face-to-face services”, these results suggest the SCP would not increase the risk of infection.

In summary, the SCP increased non-negligible consumption mainly because of its size, but the MPC is around 10% and not different from that in normal situations. Fortunately, most expenditures were for items with lower infection risks. To understand the impacts more in detail, we must use micro-data or some ‘alternative’ data to see, for example, heterogeneity across households not only in consumption but also in labour supply, although it may lower the transparency of the research.

Authors’ note: The main research on which this column is based first appeared as a Discussion Paper of the Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI) of Japan.

References

Andersen, A, E Hansen, N Johannesen, and A Sheridan (2020), "Consumer responses to the COVID-19 crisis", VoxEU.org, 15 May.

Baker, S R, R A Farrokhnia, S Meyer, M Pagel, and C Yannelis (2020), "Income, liquidity, and the consumption response to the COVID-19 pandemic and economic stimulus payments", VoxEU.org, 17 June.

Bounie, D, Y Camara, and J W Galbraith (2020), "The COVID-19 containment seen through French consumer transaction data: Expenditures, mobility and online substitution", VoxEU.org, 26 May.

Cabinet Office (2012), “How the special cash transfer affects household consumption”, Seisaku Kadai Bunseki Series 8.

Chronopoulos, D K, M Lukas, and J O S Wilson (2020), "Real-time consumer spending responses to the COVID-19 crisis and government lockdown", VoxEU.org, 06 May.

Coibion, O, Y Gorodnichenko, and M Weber (2020), "How US consumers use their stimulus payments", VoxEU.org, 08 September.

Hattori, T, N Komura, T Unayama (2021), “Impact of cash transfers on consumption during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from Japanese special cash payments” RIETI Discussion Paper Series 21-E-043.

Hsieh, C, S Shimizutani, and M Hori (2010), “Did Japan’s shopping coupon program increase spending?”, Journal of Public Economics, 94(7-8): 523-529.

Kaneda, M, S Kubota, and S Tanaka (2021), “Who spent their COVID-19 stimulus payment? Evidence from personal finance software in Japan”, Covid Economics: 1-29.

Kubota, S, K Onishi, and Y Toyama (2020), "Consumption responses to COVID-19 payments: Evidence from a natural experiment and bank account data", Covid Economics 62, 18 December.

Miguel, E (2021), “Evidence on research transparency in economics”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 35(3): 193–214.

Tomura, H (2021): “Household expenditures and the effective reproduction number in Japan: Regression analysis”, Working Paper.

Endnotes

1 See https://www.stat.go.jp/english/data/kakei/index.html