This column is a lead commentary in the VoxEU Debate "The Economics of the Second World War: Eighty Years On"

By the beginning of the 20th century, income and wealth inequality in many countries had reached new heights (Roine and Waldenström 2015, WID). Over the following decades, this trend was dramatically reversed. Why? Throughout history, catastrophic shocks had repeatedly levelled economic disparities (Scheidel 2017). The 20th century was no exception: mass mobilisation warfare that sometimes triggered radical revolution greatly narrowed the gap between elites and masses.

During WWI and its immediate aftermath, inequality declined from national all-time highs in France, Germany, and the UK. It fell even more dramatically in Russia after the Bolshevik takeover (Scheidel 2018). The biggest shock of the interwar period was non-violent: in the US, the Great Depression reduced income and wealth inequality, first on its own and then thanks to the New Deal, but largely failed to have comparable effects elsewhere. Truly widespread levelling occurred only in response to the unprecedented pressures and dislocations of WWII.

Scale

The evidence leaves no doubt about the intensity of this process (WID is the most important data repository, based on Atkinson and Piketty 2007, 2010 and more recent case studies). Across a dozen countries that were directly involved in the war, the income share of the highest-earning 1% of households declined on average by close to one-third of the pre-war share. National drops ranged from a modest 6% in New Zealand to a staggering two-thirds in Japan. The US (at one-quarter of the pre-war share), the UK (at one-third) and France (at one-half) fell in between these extremes. Germany’s record is somewhat obscured by poor data but likewise fits this pattern. Even close bystanders such as Ireland, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, and Switzerland recorded contractions of elite income shares (Scheidel 2017: 132-4, based on WID).

Figure 1 Top 1% income shares in four countries, 1935-1975 (% of income).

Source: Scheidel 2017: 131, Fig. 5.1, based on WID.

Although inequality often continued to fall for several decades after the end of the war, change unfolded much more rapidly during the actual war years. In France, for example, fully 92% of the net decline in the top 1% income share from 1938 to the early 1980s had already occurred by 1945. In the US, more than half of the corresponding net reduction between 1940 and the 1970s took place before 1945, and three-quarters in Canada. In Japan, inequality in 1945 was lower than at any time before or since, and at least by one measure the same was true of Germany in 1950. In the UK, by contrast, wartime equalisation accounted for a somewhat smaller share of the total decline, just as it did in some Nordic countries and in India (Scheidel 2017: 134-7, based on WID).

Even so, with the single exception of Sweden, in all relevant countries for which we have data, levelling was much more rapid during the war itself. In Central Europe, the effects of WWII were compounded by post-war socialism: in Poland, the top 1% income share more than halved between 1935 and 1947, before halving again by 1955. Conditions in Hungary followed a similar trajectory (WID).

The evidence for income Gini coefficients is less extensive but generally consistent with that for top income shares. In the US, different types of income Ginis fell by 7 to 10 points during the war years and stabilised thereafter. The UK was not far behind, and Japan’s income distribution appears to have undergone even more severe compression (Scheidel 2017: 137-8).

The share of all wealth owned by the richest 1% likewise declined: seven war-affected countries registered an average drop by about one-third between 1914 and 1945 (Roine and Waldenström 2015: 539). Much of this rebalancing was driven by dramatic losses at the very top. For example, the value of the largest 0.01% of estates in France fell by two-thirds during WWII, while that of the largest 1% in Japan plummeted by no less than nine-tenths (Scheidel 2017: 115, 139).

By contrast, instances of growing income inequality during WWII are extremely rare. Only Argentina and South Africa, where entrenched elites profited from the export of raw materials and foodstuffs, are currently known to have bucked the global trend. More generally, Latin America, spared the exigencies of war, served as a counterpoint to equalising developments elsewhere (Prados de la Escosura 2007: 297).

Causes

A wide range of factors converged in driving down inequality (Piketty 2014: 146-50, Scheidel 2017: 118-23, 143-64). Although their specific configuration varied by country, the underlying dynamics were the same: mass mobilisation, invasive government intervention, interruptions of international markets, and more often than not significant physical destruction caused massive economic shocks (Ransom 2019).

Capital, which was largely concentrated in the hands of the few and therefore accounted for much of existing income and wealth disparities, suffered greatly: the two world wars witnessed the most serious declines in returns on capital on record. During WWII, real returns on government short-term securities and long-term bonds turned negative, while returns on equities dwindled as well. The aggregate return on capital (r) fell short of the rate of economic growth (g), temporarily reversing the disequalising effect of Thomas Piketty’s axiom of ‘r > g’ and undermining the prominent standing of capital owners (Jordà et al. in press: Figs. 3, 5, 12).

Some countries were more heavily affected than others. France lost two-thirds of its capital stock. In Japan, which lost a quarter of its housing stock and 80% of its merchant ships, income from rent and interest disappeared almost completely, and dividends also declined sharply. In some cases, foreign or colonial assets—another prerogative of the well-off—became unavailable or inflation wiped out savings.

Desperate to sustain total war, governments of all stripes embraced economic planning: controls on wages, prices, rents, and dividends primarily targeted the wealthy and sought to mobilise and appease soldiers and workers at the expense of capitalists. Nationalisation schemes and confiscatory fiscal emergency measures rounded off these packages. Taxes on income and wealth, which had already surged during WWI, reached new and unparalleled heights: in the early 1940s, averaged across 20 countries, the top estate and income tax rates rose to one-third and almost two-thirds, respectively (Scheve and Stasavage 2016: 10).

Legacies

Acting in concert, these sudden developments could not fail to narrow the gap between economic classes. Yet, the end of hostilities merely slowed levelling without putting an end to it; in most cases, it continued for several more decades into the 1970s or 80s. Social and political change that was deeply rooted in the experience of total war ensured a more even distribution of the gains from strong economic growth (Scheidel 2017: 164-73).

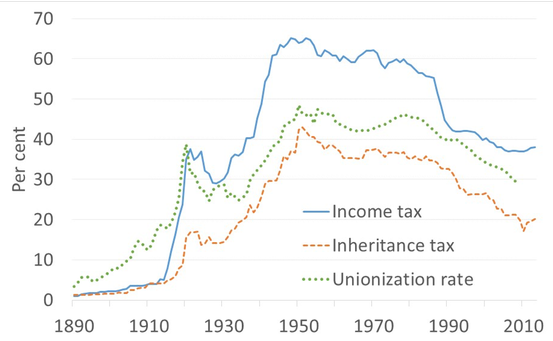

Until the 1970s, top tax rates often remained at levels close to those reached during WWII (Roine and Waldenström 2015: 556, Scheve and Stasavage 2016: 10). While income taxes flattened take-home pay, wealth taxes retarded the rebuilding of large fortunes. Unionisation was instrumental in ensuring wage compression. Union membership peaked in the wake of WWII: in 1945 in the US, and on average five years later in a sample of 10 OECD countries (Scheidel 2017: 166-7).

Figure 2 Mean top rates of income and inheritance taxes in 20 countries and mean trade union density in 10 countries, 1890-2010 (%).

Sources: Scheve and Stasavage 2016: 10, Fig. 1.1; Scheidel 2017: 167, Fig. 5.13, from https://www.macro.economics.uni-mainz.de/klaus-waelde/trade-union-density-from-1880-to-2008-for-selected-oecd-countries/.

Extensions of the right to vote, which had surged in and right after WWI, once again gathered steam. More generally, the shared experience of total war helped shape attitudes and outcomes: conscription and rationing, often coupled with evacuations, bombing, or worse, eroded class distinctions and raised expectations of fairness and inclusion. Thus, the war served as a crucial catalyst for the creation of the welfare state (e.g. Klausen 1998). WWII created both the political will and the fiscal and organisational capacities required for ambitious redistributive programmes.

It is true that in all of this, other factors such as education and technology also played a major role. Even so, the political initiatives that had been precipitated by the pressures of war provided an indispensable framework for equalising change. As Sir William Beveridge put it in 1942, “Now, when the war is abolishing landmarks of every kind, is the opportunity for using experience in a clear field. A revolutionary moment in the world’s history is a time for revolutions, not for patching” (Beveridge 1942: 6).

Genuinely ‘revolutionary’ change was limited to Eastern and Central Europe and China. During the late 1940s, Stalin’s and Mao’s forces imposed socialism on a quarter of the world population. By 1950, one in three people on earth lived under communist regimes. Yet, at the same time, the market economies of Western Europe, North America and the Pacific Rim—which together accounted for more than another fifth of humankind—also went a long way in promoting an egalitarian agenda.

Sustained by economic growth that ensured full employment and strengthened the bargaining power of the masses, the institutional legacies of mass-mobilisation warfare managed to meld material progress with gentle levelling. By now an increasingly distant memory, post-war equality cannot be separated from the formative experience of WWII.

References

Atkinson, A B, and T Piketty (eds.) (2007), Top income over the twentieth century: A contrast between continental European and English-speaking countries, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Atkinson, A B, and T Piketty (eds.) (2010), Top incomes: A global perspective, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Beveridge, W (1942), Social insurance and Allied services, London: His Majesty’s Stationery Office.

Jordà, Ò, et al. (in press), “The rate of return on everything, 1870-2015”, Quarterly Journal of Economics.

Klausen, J (1998), War and welfare: Europe and the US, 1945 to the present, New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Piketty, T (2014), Capital in the twenty-first century, Cambridge US: Harvard University Press.

Prados de la Escosura, L (2007), “Inequality and poverty in Latin America: A long-run exploration”, in T Hatton et al. (eds.), The new comparative economic history: Essays in honor of Jeffrey G. Williamson, Cambridge US: MIT Press, pp. 291–315.

Ransom, R (2019), “War and cliometrics in an age of catastrophes”, in C Diebolt and M Haupert (eds.), Handbook of cliometrics, Berlin: Springer.

Roine, J, and D Waldenström (2015), “Long-term trends in the distribution of income and wealth”, in A B Atkinson and F Bourguignon (eds.), Handbook of income distribution, Volume 2A, Amsterdam: North-Holland, pp. 469-592.

Scheidel, W (2017), The great leveler: Violence and the history of inequality from the Stone Age to the twenty-first century, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Scheidel, W (2018), “Inequality: From the Great War to the great compression”, in S Broadberry and M Harrison (eds.), The economics of the Great War: A centennial perspective, London: CEPR Press, pp. 145-152.

Scheve, K, and D Stasavage (2016), Taxing the rich: A history of fiscal fairness in the US and Europe. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

WID, “World inequality database”, https://wid.world/.