Economists generally view innovation as the most significant driver of long-run productivity growth. At the firm level, however, our understanding of the relationship between intellectual property (IP) protection, R&D investment, and innovation outcomes has long been hampered by measurement problems and a lack of data.

The notable exceptions to this gap in our knowledge about private innovation incentives are the Yale and Carnegie surveys conducted by Levin et al. (1987) and Cohen et al. (2000), which asked R&D managers about their firms’ strategies for appropriating the value of their innovations. Yet these surveys are now more than 20 years old. Furthermore, for practical reasons the Yale and Carnegie surveys focused on large firms in manufacturing industries, leaving us with relatively little knowledge about the incidence of R&D or the importance of IP in small companies or other sectors.

In a recent paper (Mezzanotti and Simcoe 2023), we revisit the broad question of how firms appropriate the benefits of innovation using survey data collected by the US Census between 2008 and 2015. Our results suggest that many patterns uncovered in previous literature have persisted. For example, most US firms still indicate that they view trade secrecy as the most important type of IP protection. At the same time, our analysis uncovers some new stylised facts, and highlights a strong link between firm size and engagement with formal IP protection.

IP activity by US firms

Our data come from the Business R&D and Innovation Survey (BRDIS), which aims to provide a representative picture of R&D activity conducted by for-profit, nonfarm businesses with five or more employees operating in the United States.

Three features of the BRDIS data are particularly important for our analysis. First, unlike the earlier Yale and Carnegie surveys, BRDIS covers a large representative sample of firms. Second, the survey combines quantitative measures of IP use (e.g. patent counts) with qualitative variables that report the perceived importance of different forms of IP protection strategies by a company. The qualitative measures facilitate the comparison of preferences across different firms and allow us to explore business practices (e.g. trade secrets) that are intrinsically hard to observe and quantify. Third, the survey data provides researchers with sampling weights that allow us to generate statistics representative of the average US firm.

Our paper is organised around five stylised facts.

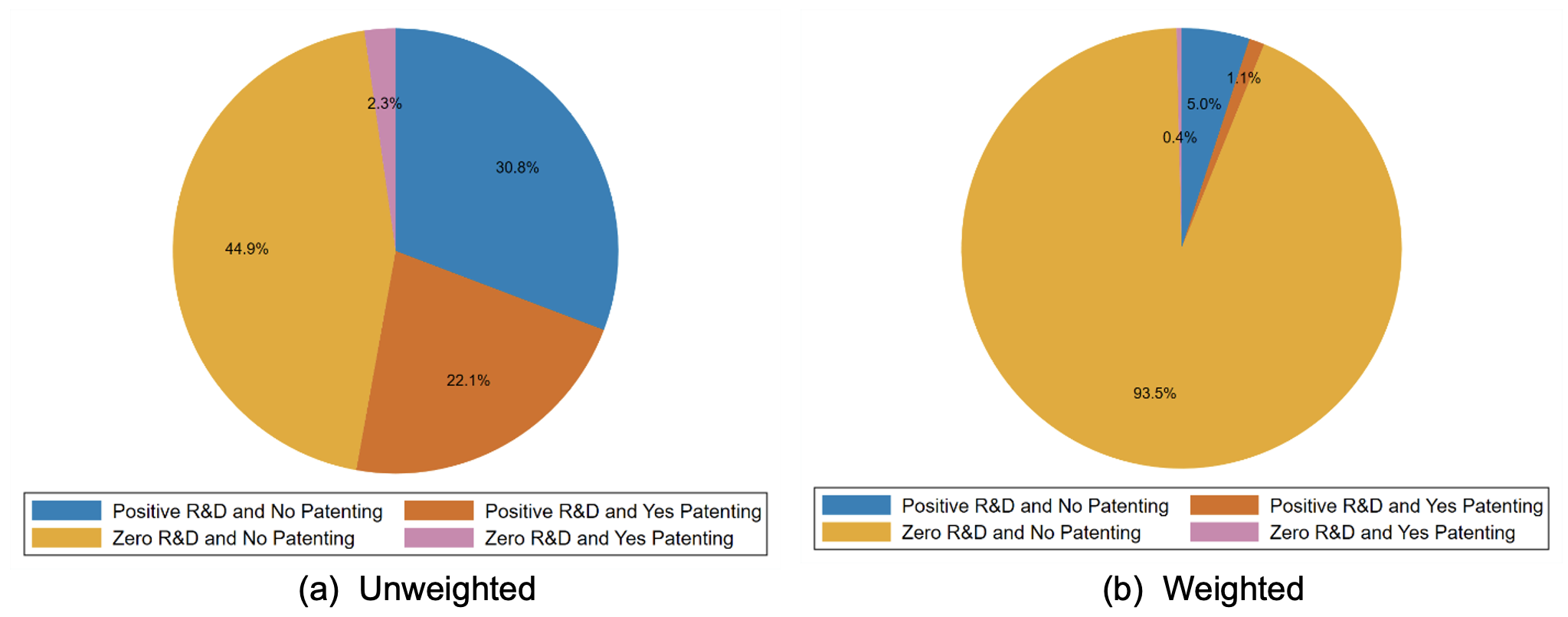

Fact 1: Patenting is relatively uncommon in the economy, but most R&D is concentrated among patenting firms.

Patenting firms are relatively scarce within the US economy (Figure 1). Less than 2% of all companies are patenting firms, meaning that they patented at least once over a five-year period. This small group of patenting companies is particularly important, however, because they perform over 90% of US R&D investment.

Figure 1 Composition of firms by patenting activities and R&D spending

Note: These pie charts report the (unweighted) share of firms in the data used split based on whether the firm is conducting R&D in the year of the survey and whether the firm is labelled as patenting firm, following the usual definition. In panel (a), we conduct this analysis without any adjustment from the raw BRDIS sample, while in panel (b) we incorporate sampling weights. The actual percentages per group are reported in the figure.

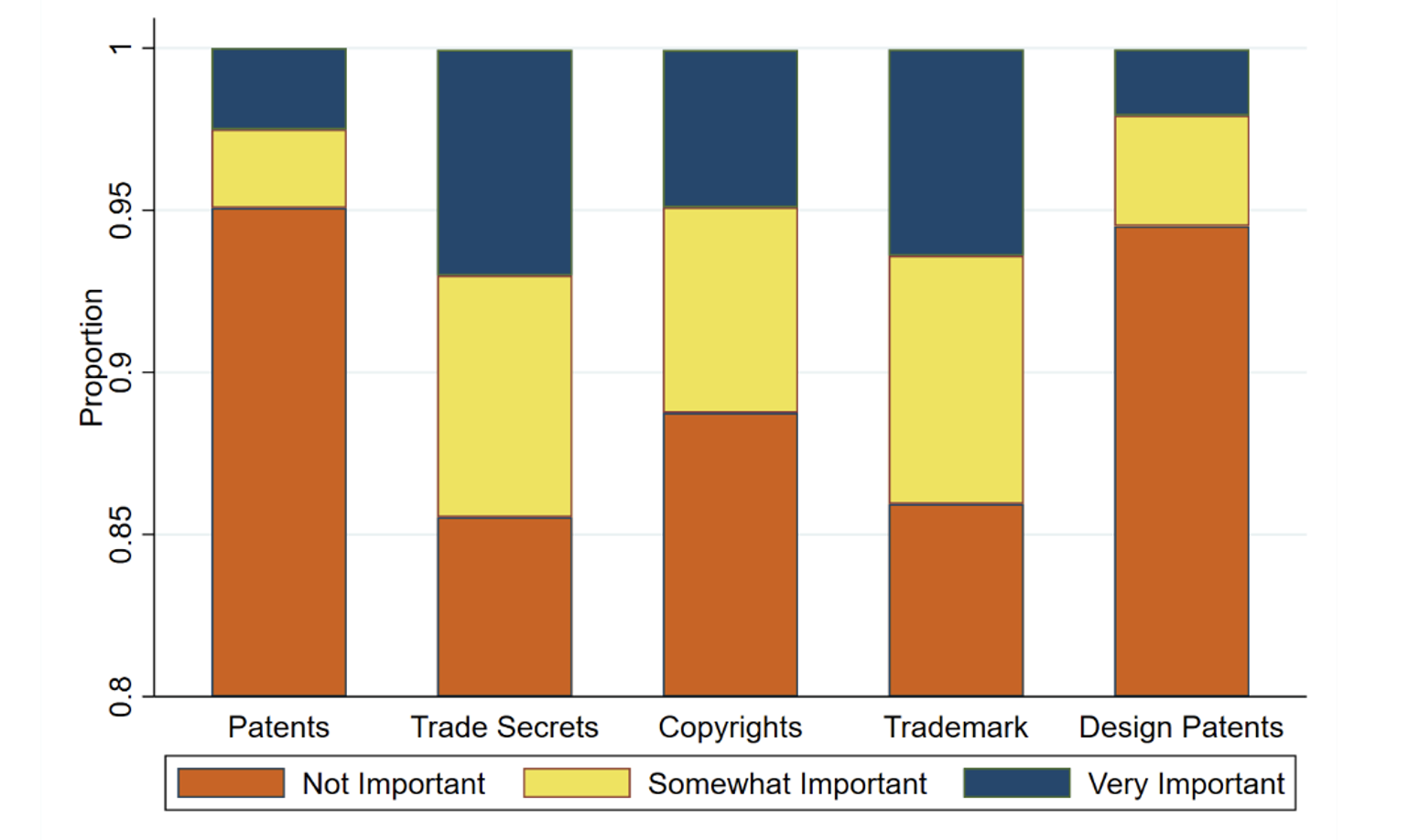

Fact 2: Patenting is not the main strategy to protect IP

Patents are generally not considered the most important tool for appropriating the benefits of an innovation. In the unweighted sample, around two-thirds of surveyed firms report that utility patents are not important. For the nationally representative sample, around 95% of firms report utility patents are not important, as shown in Figure 2. In relative terms, patents are consistently considered significantly less important than trade secrets, (and to a lesser extent) copyrights and trademarks.

Figure 2 Importance of different IP protection strategies, all firms

Note: This bar graph reports the weighted share of response by firms to the question: During this past year, how important to your company were the following types of intellectual property protection? This example question is modelled on the 2008 version. We consider five types of protections: patents, trade secrets, copyrights, trademarks, and design patents.

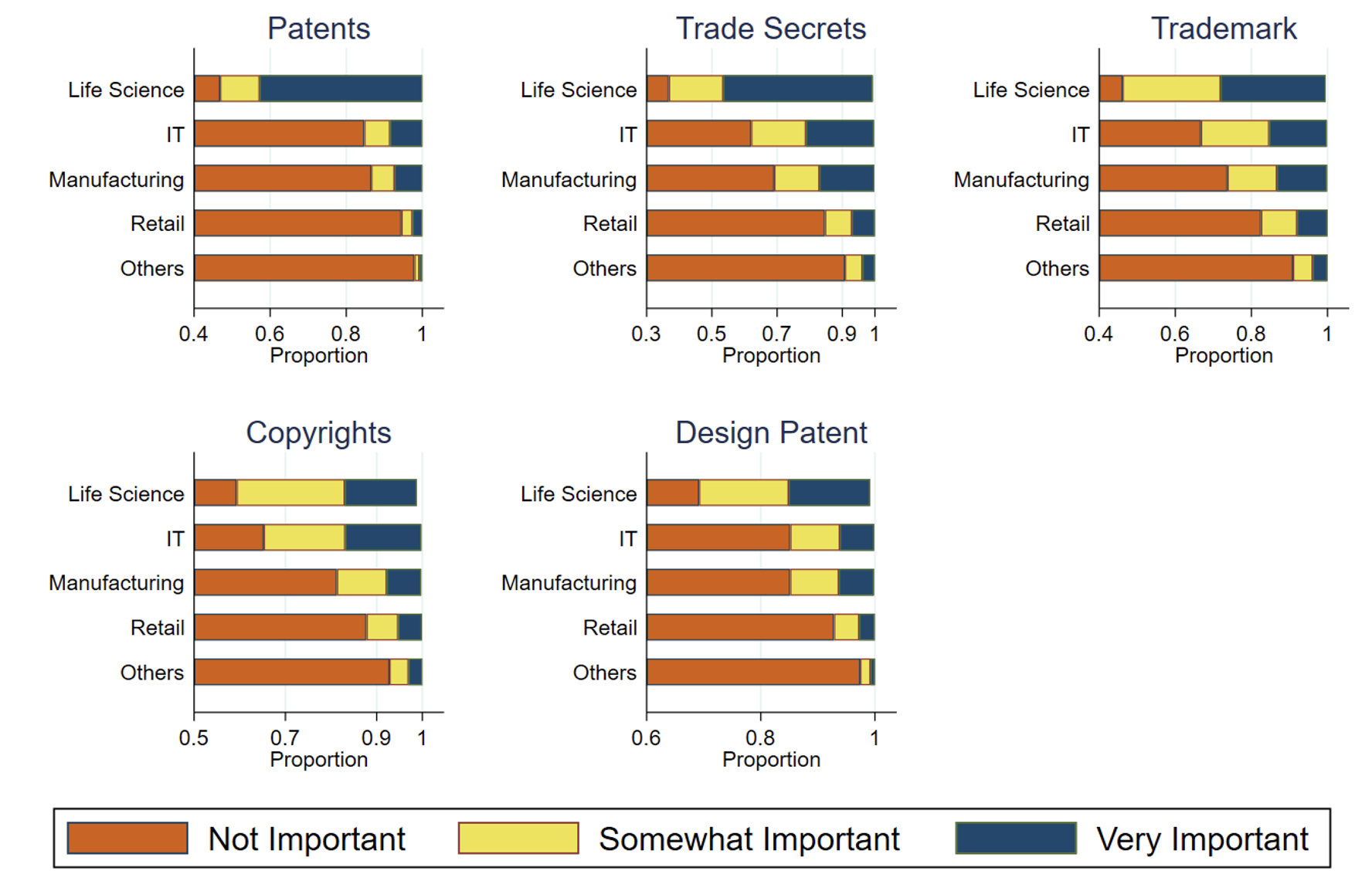

Fact 3: The importance of IP varies with product market characteristics

Figure 3 shows the stated importance of different types of IP protection across macro industries for the BRDIS sample without weight adjustments. Companies in the Life Sciences and the Information Technology sector consistently report that all forms of IP protection are more important. In general, however, the relative importance of different types of IP does not vary significantly by industry (except for the outsized importance of patents to Life Science and perhaps copyrights to IT firms). Outside of high-tech, manufacturing, and retail, the perceived importance of IP is very low. For example, on a nationally representative basis, only 2% of firms outside high-tech, manufacturing, and retail report that patents have any importance.

Figure 3 Importance of different IP protection strategies by industry

Note: This set of bar graphs reports the weighted share of response by firms to the question: During this past year, how important to your company were the following types of intellectual property protection? This example question is modeled on the 2008 version. We consider five types of protections: patents, trade secrets, copyrights, trademarks, and design patents. Each panel focuses on a different form of protection and reports the share of responses in each category by macro industry classification. In particular, we split the sample in Life Science, IT, Manufacturing, Retail, and others (residual category).

Fact 4: The importance of IP does not change as firms age

Perhaps surprisingly, we find no systematic relationship between firm age and our measures of IP strategy. This result is robust to controlling for industry effects, firm size, R&D intensity, and other factors. One way to interpret this finding is that a firm’s IP policy might be modelled as a state variable that is determined at founding and remains constant over the life of the business. Consistent with this idea, we show that early decisions of a firm regarding R&D and patenting strongly predict future growth, as in Guzman and Stern (2020).

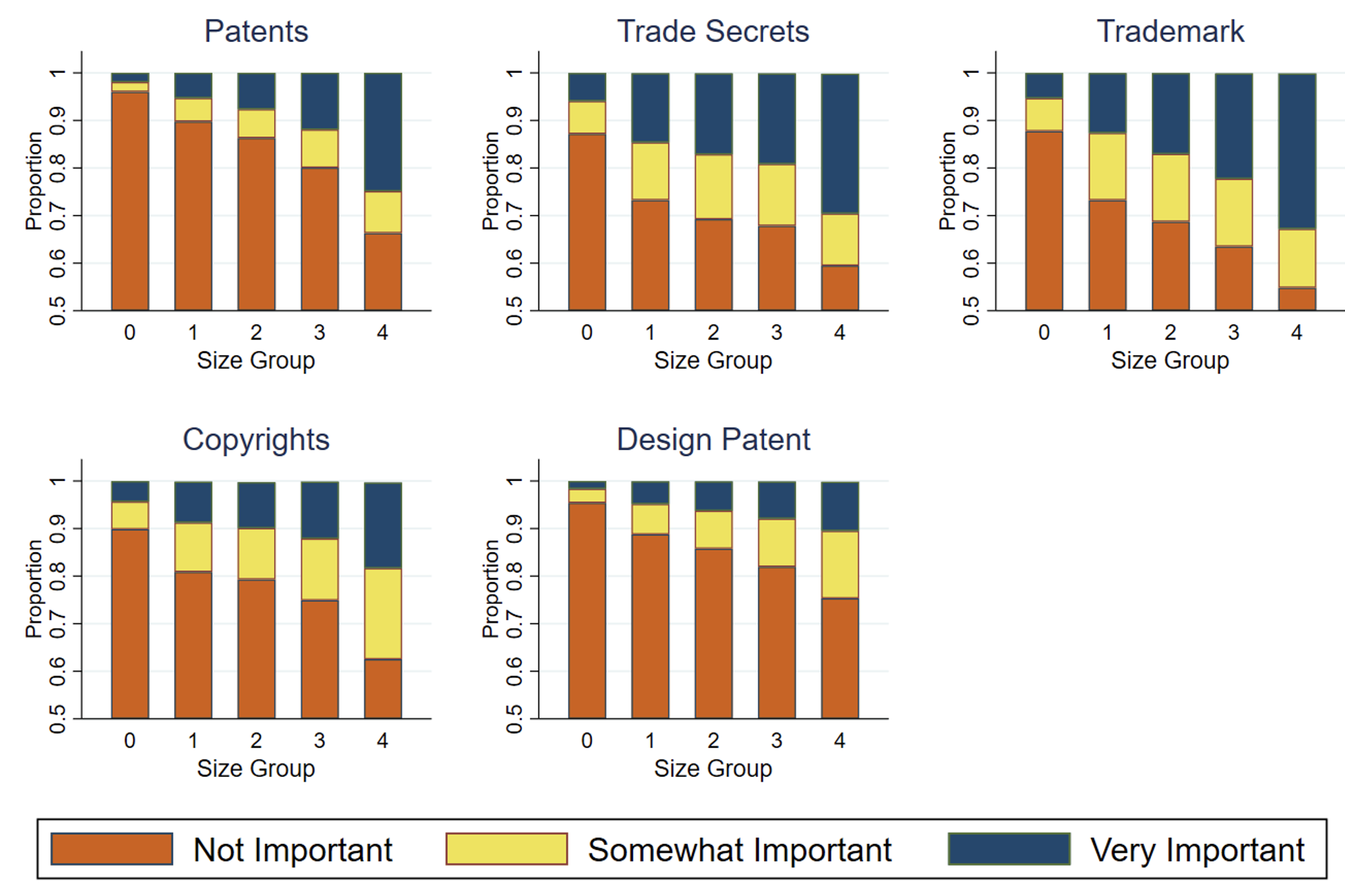

Fact 5: Larger firms are systematically more active in IP protection, across all forms of protection

In contrast to age, we find that firm size is an important determinant of firms' IP strategies. This relationship is monotonic and economically significant across all types of intellectual property. For instance, within the BRDIS sample, a firm in the largest size bucket considers patents three times more important than those in the smallest bucket (Figure 4). This relationship between firm size and patenting is robust to controlling for other characteristics of the firm, including industry, age, R&D investment, innovation output, expertise in the market for technology, and the use of other types of IP. Finally, we show that firm size explains a significant share of the total variance in IP use. Overall, the evidence is consistent with the view that business scale is an important determinant of firms’ decision to use formal IP (Argente et al. 2020).

Figure 4 Importance of different IP protection strategies by firm size group

Note: This set of bar graphs reports the weighted share of response by firms to the question: During this past year, how important to your company were the following types of intellectual property protection? This example question is modeled on the 2008 version. We consider five types of protections: patents, trade secrets, copyrights, trademarks, and design patents. Each panel focuses on a different form of protection and reports the share of responses in each category by groups of firm size (using worldwide sales as proxy). The five groups are defined as followed: (0) 0-10 million; (1) 10-25 million; (2) 25-100 million; (3) 100-1000 million; (4) 1000+ million. All values are in US dollars nominal terms.

Conclusion

The stylised facts we put forward in our study can be informative for both academics and policymakers who are interested in understanding the role of IP in explaining important recent trends in our economy. For instance, recent research has begun to investigate determinants of the economic advantages of large firms in developed economies. In this context, Arora et al. (2023) argue that part of this advantage may stem from large firms’ superior ability to extract value from inventions. Our work provides direct evidence on one of the possible mechanisms that may explain the result in Arora et al. (2023): a more aggressive use of IP protection among large firms. This evidence is also consistent with Schankerman and Galasso (2016), suggesting that patent rights may play a different role between large and small businesses. More broadly, our study contributes to the literature on the determinants of innovation activity, helping to foster the debate on the optimal way to foster innovation, as discussed in Lerner (2013).

References

Argente, D, S Baslandze, D Hanley and S Moreira (2020), “From patents to products: Product innovation and firm dynamics”, VoxEU.org, 28 May.

Arora, A, W Cohen, H Lee and D Sebastian (2023), “Invention value, inventive capability and the large firm advantage”, Research Policy 52(1): 104650.

Cohen, W, R Nelson and J Walsh (2000), “Protecting their intellectual assets: appropriability conditions and why U.S. manufacturing firms patent (or not)”, NBER Working Paper 7552.

Guzman, J and S Stern (2015), “Where is Silicon Valley?”, Science 347(6222): 606-609.

Levin, R, A Klevorick, R Nelson, S Winter, R Gilbert and Z Griliches (1987), “Appropriating the returns from industrial research and development”, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 1987(3): 783-831.

Lerner, J (2013), “The architecture of innovation”, VoxTalk, 21 March.

Mezzanotti, F and T Simcoe (2023), “Innovation and Appropriability: Revisiting the Role of Intellectual Property”, NBER Working Paper.

Schankerman, M and A Galasso (2016), “Patent rights and innovation by small and large firms”, VoxEU.org, 7 January.