Throughout history, rulers have faced challenges to their rule from outside aggressors, popular uprisings, or elite conspiracies. The ability of rulers to respond to these challenges has varied significantly across countries and over time (e.g. Cagé et al. 2021). In a recent paper (Roland et al. 2021), we propose a theory of power structure based on the relative powers of three main actors: the ruler, the elite, and the people. Our theory is based on two important variables: first, the absolute power of the ruler; and second, the level of asymmetry in the power and rights of the elite versus ordinary people. We apply this theory to the historical context of feudal Europe versus Imperial China, focusing on the period between the 9th and 14th centuries.

Why does power structure matter? Political economy theories of institutions and development usually focus on the relationship between the ruler and the ruled – in other words, on the first element of a power structure: The absolute power of the ruler over the ruled. These theories rightly emphasize how constraints on the power of the ruler are good for the protection of property rights (e.g. Besley and Ghatak 2009). The theories capture essential elements of European history where constraints on the power of rulers were favourable to the property rights of the elite, essentially the landed and hereditary aristocracy. However, these theories leave out the fact that ordinary European peasants had virtually no rights at all and were oppressed by elites and rulers, with little hope for social mobility. In contrast, the absolute power of Chinese Emperors was much more developed, which made property rights for the ruled less secure. At the same time, the rights and powers of the elite versus ordinary people were less imbalanced. Ordinary people had the possibility of joining the elite via the Civil Service Exam, peasants were more autonomous, and land ownership was much less concentrated than in Europe. In other words, there was a stronger asymmetry between the power and rights of the elite versus the people in feudal Europe compared to China, the second variable in our theory of power structure.

Why does this more complete theory of power structure matter? Why not focus only on the degree of absolute power of the ruler? Our model of power structure and challenges to the rulers provides an answer. Without explaining the model in detail, our main results are the following. First, providing more rights to the people reduces their incentives to mount or join a challenge to the ruler, as they have more to lose if the challenge fails and they are punished. We call this the ‘punishment effect’. Second, reducing people’s incentive to join a challenge to the ruler also reduces the incentive of the elite to mount or join a challenge to the ruler. We call this the ‘political alliance effect’. These effects work to stabilise autocratic rule. Note that stronger absolute power of the ruler means the power and rights of the ruled depend more on the ruler’s will, which serves, ceteris paribus, to strengthen the punishment effect and, therefore, the total stabilising effect. Increased absolute power will thus give the ruler a stronger incentive to create more symmetric relationships between the elite and the people. This may explain why China had both more absolute power of the ruler and a stronger symmetry between the elite and the people compared to Europe.

A direct implication of this theory is that, given both the stronger absolute power of the ruler and a more symmetric elite-people relationship, we should observe fewer challenges to rulers and a higher stability of autocratic rule in Imperial China relative to Europe.

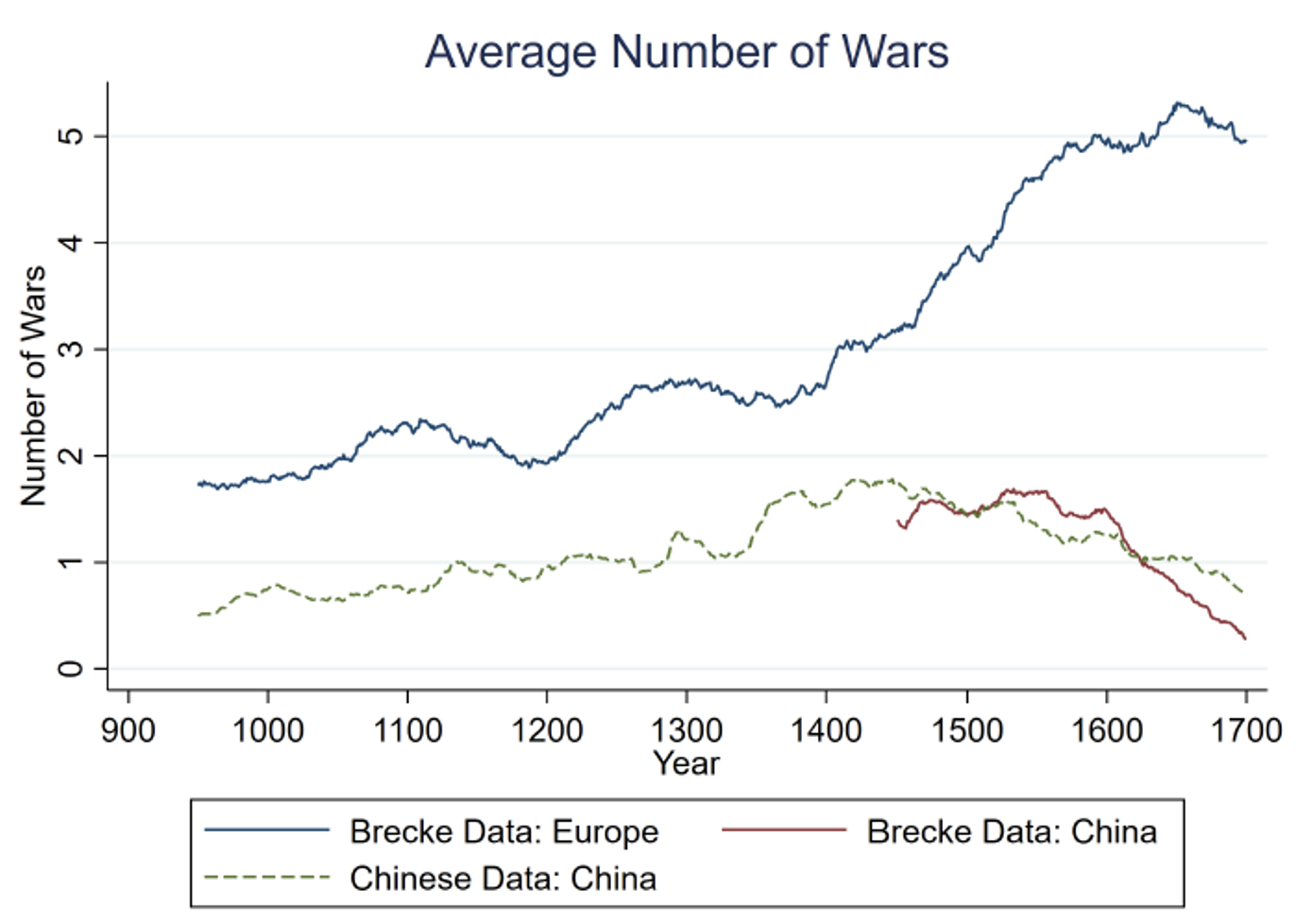

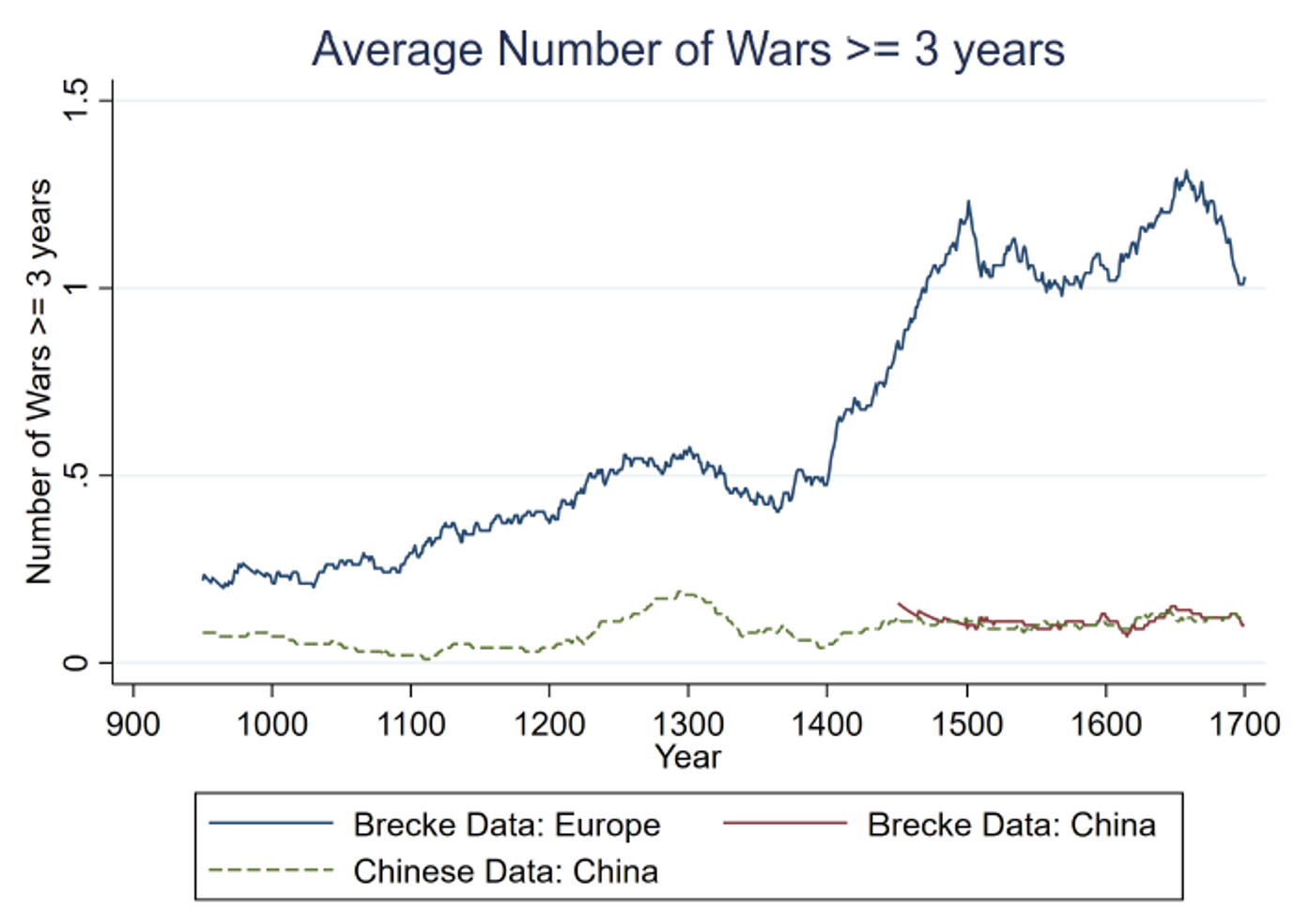

If we interpret challenges to the ruler as ‘wars’, we can compare the occurrences of wars (civil wars or wars of aggression) in Europe to those in China. Using data on wars from Brecke (1999) between 900 and 1400 CE, and complementing them with information from Chinese Military History (2003) from 900 CE onwards, Figure 1 (panel A) below displays 100-year moving averages of the number of wars started in a given year (based on the Olympic average, i.e. after removing one of the highest and lowest values in the window). There were indeed significantly fewer wars in China than in Europe. Figure 1 (panel B) does the same but only looks at wars that lasted three years or more, and the pattern is similar.

Figure 1

a) All wars

b) All three-year or longer wars

Note: Olympic average with each retrospective 100-year window. Data sources: Brecke (1999) for the "Brecke data", Chinese Military History (2003) for the "Chinese data".

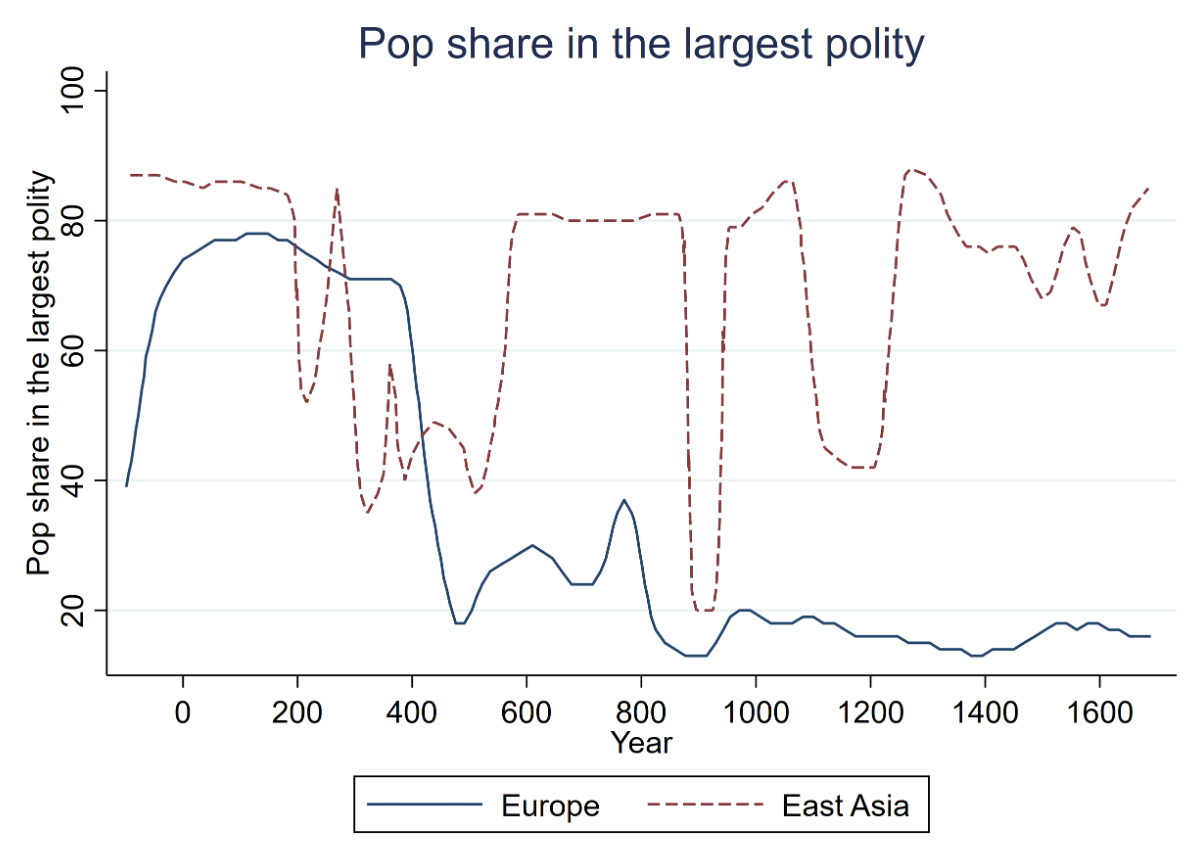

If we interpret the ruler being challenged as one ‘ruling a large, unified territory’, and challenges as ‘attempts to secede’, then the model implies that a unified autocratic rule should have been more resilient in China than in Europe. Figure 2 (based on Scheidel 2019) compares the share of the population in Europe versus East Asia that was controlled by the largest polity. As can be seen from Figure 2, that number in East Asia was, with some exceptions, above 75%, showing the stability of China as a dominant Empire. In contrast, the number for Europe was usually below 20%, confirming the general fragmentation of Europe after the fall of the Roman Empire, even taking into account the short period when Charlemagne unified large parts of Europe.

Figure 2

Another implication of the theory is that it is possible for the people to be better-off in equilibrium when their rights and power can be taken away by the ruler, because it makes their power and rights conditional on their submission to the ruler. Therefore, they may be satisfied with a weak rule of law, a balanced elite-people relationship, and a stable autocratic regime. Although we do not fully endogenize the absolute power of the ruler, in a dynamic extension, we show that China and Europe can be understood as different steady states in a dual divergence of power structure and autocratic stability, in which stability facilitates the ruler’s investment in the power structure.

Conclusion

Our theory of power structure emphasises differences in the absolute power of rulers relative to the ruled, and differences in the power and rights of elites versus the people. The theory enriches our understanding of institutional compatibilities in a comparative framework and sheds light on differences between feudal Europe and Imperial China. It helps to understand why Chinese rulers, who had more absolute power, also had more incentives to create symmetry in the power and rights of elites versus the people. The resulting differences in political stability certainly affected later economic development, as reflected in debates among economic historians about the ‘great divergence’ between China and Europe (see e.g. Rosenthal and Wong 2011, van Zanden 2011). Stylised data on the occurrence of wars and fragmentation of polities are consistent with our model. Our theory can be used to analyse other historical contexts than those analysed here. We hope this will encourage other researchers to use and expand our power structure framework.

References

Besley, T and M Ghatak (2009), “Reforming property rights”, VoxEU.org, 22 April.

Brecke, P (1999), “Violent conflicts 1400 AD to the present in different regions of the world”, Paper prepared for the 33rd Peace Science Society (International), 8–10 October, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Cagé, J, A Dagorret, P Grosjean and S Jha (2021), “

”, VoxEU.org, 17 January.

Chinese Military History (2003), Chronicle of Wars in the Chinese History, Beijing: People's Liberation Army Publishing House.

Jia, R, G Roland and Y Xie (2021), “A Theory of Power Structure and Institutional Compatibility: China vs. Europe Revisited”, CEPR Discussion Paper 15700.

Wong, R B and J-L Rosenthal (2011), Before and Beyond Divergence: The Politics of Economic Change in China and Europe, Harvard University Press.

Scheidel, W (2019), Escape from Rome: The Failure of Empire and the Road to Prosperity, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Van Zanden, J L (2011), “Before the Great Divergence: The modernity of China at the onset of the industrial revolution”, VoxEU.org, 26 January.