The war in Ukraine has already caused the forced displacement of more than 8 million people (not counting internally displaced persons), including 5 million who received temporary protection from the EU in various member countries. The main hosting countries are Poland (1.5 million), Germany (1 million), the Czech Republique (0.5 million), with the numbers in France, Italy, or other countries rarely exceeding 100,000 refugees. As its name suggests, temporary protection is short-lived. Once the threat of war vanishes and people’s security can be guaranteed, the temporary protection will be lifted. In the meantime, that status allows Ukrainian refugees to freely circulate and work within the EU. This is something noteworthy as it differs from the situation of the millions of asylum seekers who, in most EU countries, cannot work until their asylum claim is examined and they are granted refugee status, which takes one to two years on average. In principle, that time can be used to acquire language and other skills that can favour a better integration in the future. In practice, however, longer delays to access the labour market translate into substantial penalties in terms of labour market participation and wages. This is shown for example in a series of works by Francesco Fassani and co-authors (e.g. Fasani et al. 2021).

In the policy debate on labour market access for refugees, the perspective of source countries is often completely neglected. However, there is an important positive externality for home countries from early labour market access for its refugees. Indeed, while at work, refugees accumulate experience, savings, knowledge, and know-how that will eventually be repatriated upon their return. In doing so, they will contribute to reconstruction efforts at home, thereby complementing reconstruction aid from the international community (Rashkovan and Eichengreen 2022, Dlankov and Blinov 2022). It is therefore particularly worthy of praise that the EU has immediately authorised not only the free entry and circulation of Ukrainians on its soil but also granted them instantaneous access to its labour markets.

To understand why this is the case, we need to look for a similar context in the recent past, to conduct a ‘natural experiment’. The last time a large number of people were forcibly displaced from their homes within Europe dates back to the early 1990s, during the wars of secession in the former Yugoslavia. Between 1991, when the first republics (Slovenia and Croatia) seceded and the end of the year 1995 (when the Dayton peace agreement put an end to the war in Bosnia), nearly 4 million Yugoslavians had been displaced, including nearly 1 million who fled abroad, mostly (for 700,000 of them) to Germany. Germany granted them temporary protection (‘duldung’, or ‘toleration’ in German) allowing them to circulate and work freely in Germany as long as their 6-month permits were renewed. Starting in 1996, the German government stopped renewing the permits, which led to the effective deportation (according to the UNHCR) of more than 75% of the refugees. For the most part, they returned to the former Yugoslavian republics that had become independent as a result of the partition of Yugoslavia.

How did those returning refugees contribute to the reconstruction of their home countries? My co-authors and I study this question (Bahar et al. forthcoming). We use exports, disaggregated into 800 industries, i.e. to the SITC 4-digit level, as an indicator of economic performance. We show that the industries which experienced strong export growth during the 2000s in the newly independent states of the former Yugoslavia were precisely those where Yugoslavian refugees used to work in Germany between 1991 and 1995. More precisely, we use confidential German social security data to record the number of workers born in Yugoslavia, entering the records of the German social security after 1990 and before 1996 (hence, making it almost certain that they were displaced by the war), working in manufacturing, and who had disappeared from such records by the year 2000 (making it very likely they had returned). We take that number at the industry level as our ‘treatment’, which we interpret as the intensity of exposure of Yugoslavian workers to German technology, one of the most advanced in the world in virtually all manufacturing sectors.

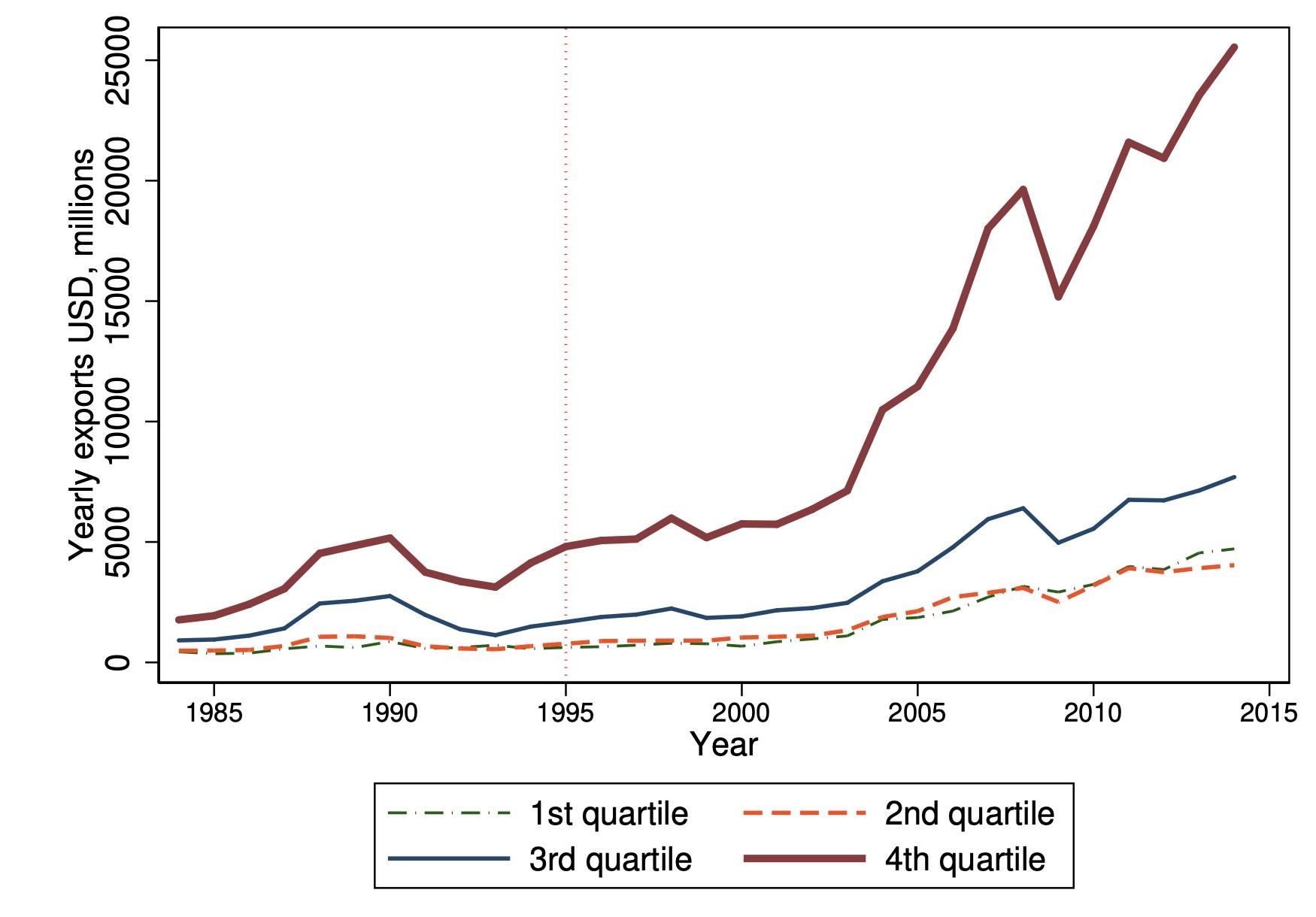

Figure 1 The effect of returning refugees on export performance in the former Yugoslavia (by quartile of treatment intensity)

Using econometric techniques (differences-in-differences with instrument variables) that allow for a causal interpretation of the results, we show that the industries that happened to be more intensely ‘treated’ had significantly better export performance in the post-war period. For example, our point estimates suggest that doubling the number of returning refugees in a given industry generates a 15% increase in the volume of exports in the 2000s. We also show that this effect cannot be explained by exports to Germany (which could be explained by network effects) but by exports to the rest of the world (excluding, for comparability with export data in the pre-war period, trade between the former Yugoslavian republics), which can be explained by productivity shocks resulting from the skills, knowledge, and know-how accumulated by Yugoslavian refugees while working in manufacturing in Germany and repatriated with them and eventually transferred to their home countries upon return.

Overall, we estimate that more than 6% of all export growth of the former Yugoslavian republics can be attributed to returnees. A contribution which is, therefore, not just statistically significant but also economically quite substantial. And something to keep in mind when gauging the costs and benefits of future labour-market access regulations for current and future refugees, from Ukraine and beyond.

References

Bahar, D, A Hauptmann, C Özgüzel and H Rapoport (forthcoming), “Migration and Knowledge Diffusion: The Effect of Returning Refugees on Export Performance in the Former Yugoslavia”, The Review of Economics and Statistics, forthcoming.

Djankov, S and O Blinov (2022), “Ukraine’s recovery challenge”, VoxEU.org, 31 May.

Fasani, F, T Frattini and L Minale (2021), “Lift the ban? Initial Employment Restrictions and Refugee Labour Market Outcomes”, Journal of the European Economic Association 19(5): October.

Rashkovan, V and B Eichengreen, “How to organise aid”, VoxEU.org, 12 December.