With inflation recently breaching 10% in many advanced economies for the first time in decades, an entire generation has lived through its first bout of significant and sustained price increases (Kose et al. 2022). How will this experience shape their beliefs in the future? Earlier evidence, surveyed in Malmendier and Wachter (2023), shows that cataclysmic macroeconomic events can significantly shape the beliefs and economic decisions of a generation – from Americans who experienced the Great Depression (Malmendier and Nagel 2016) to Germans who lived through hyperinflation in the 1920s (Braggion et al. 2023). The recent inflation spike is of an order of magnitude smaller than these catastrophes. Will its effects therefore rapidly fade, or will it leave scarring effects on how people perceive inflation and monetary policy in the future? This is a pivotal question for central banks, considering the imperative to anchor the public’s inflation expectations to low inflation targets to forestall the entrenchment of higher inflation.

Our recent research (Salle et al. 2023) seeks to answer this question by using both a large-scale household survey of the Dutch population and a laboratory setting with students at the University of Amsterdam during the recent inflation peak in the Netherlands. Our results suggest that the recent rise of inflation may have long-lived effects on people’s inflation expectations, potentially complicating the central banks’ efforts to stabilise inflation for years ahead.

Individual memories are more diverse than common historical experiences

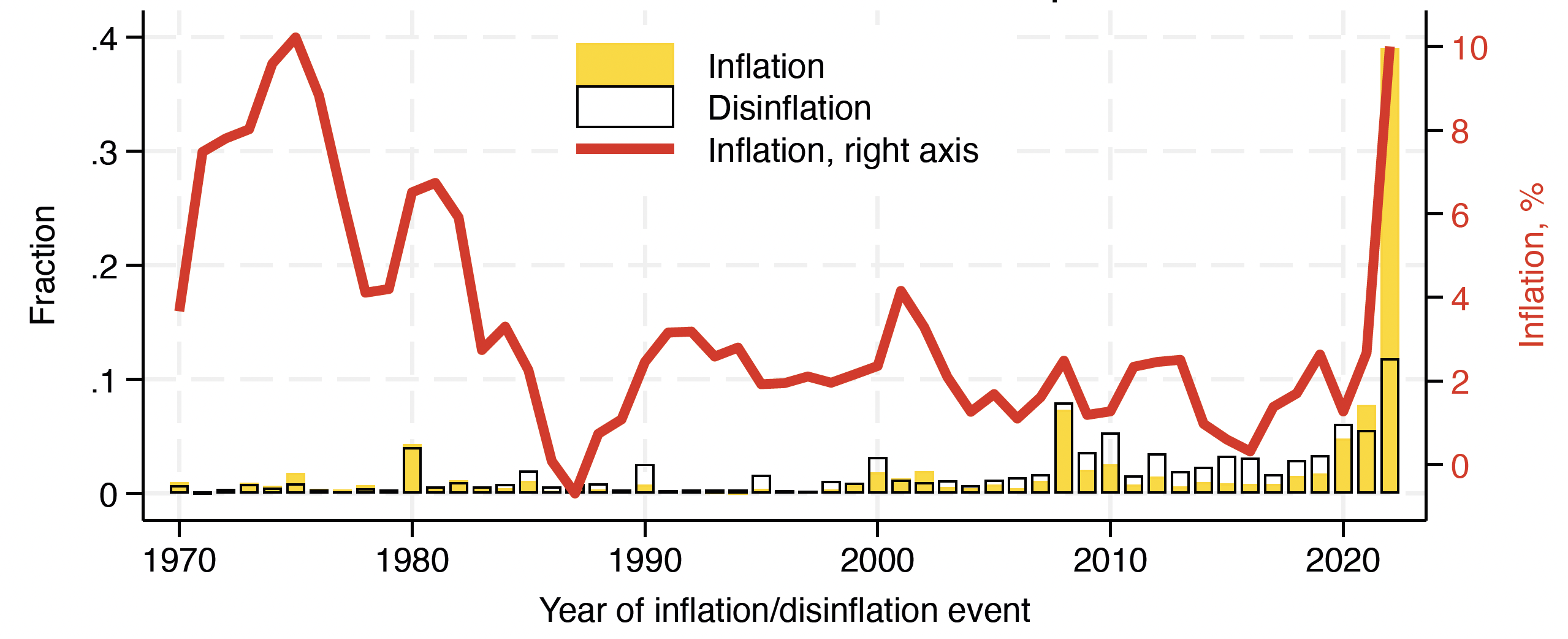

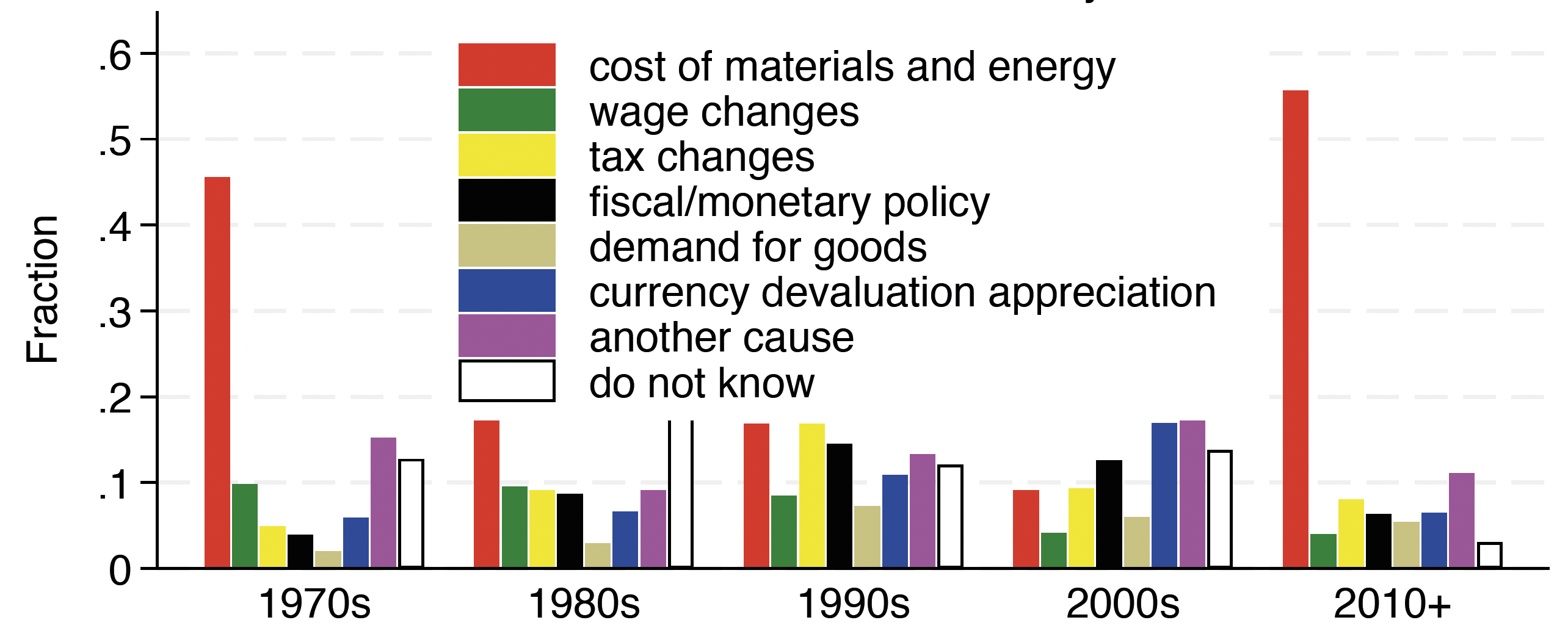

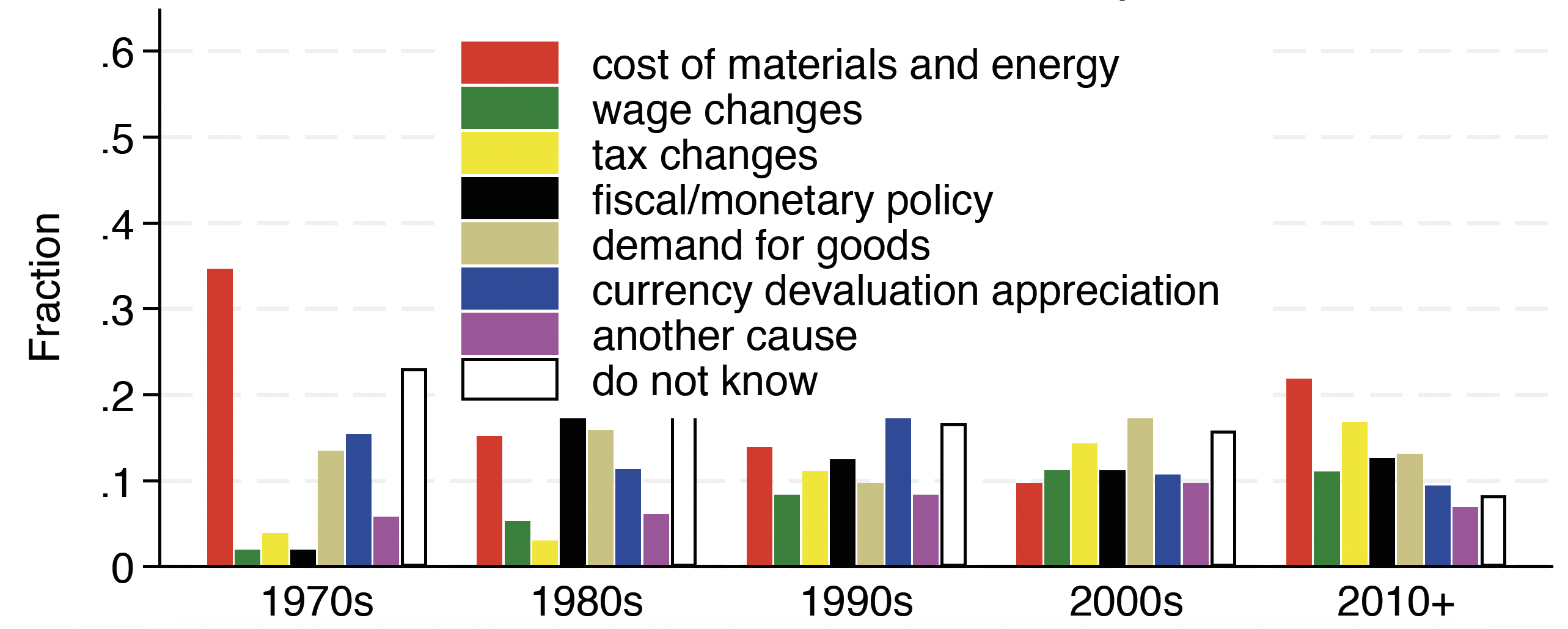

We first asked the lab participants and the survey respondents to describe up to two episodes of rising and decreasing inflation over their lifetime. They were invited to specify the time and location, recall the lowest and highest inflation rates, note the amplitude of the changes, rate their confidence in their memory, identify the perceived cause, and describe the impact on their personal finances. We find that individual memories differ greatly, even across individuals belonging to the same generation. Panel A of Figure 1 plots the distribution over time of inflation surges and disinflations cited by survey respondents. Overall, participants are more likely to recall rising rather than decreasing inflation, with a large spike around 2021 and 2022, where around 40% of survey participants recall an inflation surge. A second spike in both inflation and disinflation memories occurs around 2008–2010, when substantial changes in food and commodity prices occurred in the wake of the Global Crisis. A smaller spike in recollections happens around 1980, when inflation in the Netherlands was high and volatile, leading households to recall both the inflation surge and subsequent disinflation. Another example of this variation is the reported causes of these changes in inflation (see, respectively, Panels B and C of Figure 1). Episodes in the 1970s and from the 2010s were more likely to be attributed to input and energy cost changes than during the 1980s–2000s. Disinflation in the 1990s is attributed by many people to currency changes, consistent with the large appreciation of the Dutch guilder around this time. For the 1980s, many do not remember the reasons for disinflation, but about 35% of those who do remember attribute disinflation to policy or lower demand for goods, with another 15% emphasising energy and input price changes. We also find a salient asymmetry when it comes to the effect of these episodes on household finance: while most respondents report that inflation surges made them worse off, there is little agreement about whether disinflations made them better off.

This range of recollections clearly indicates that individual experiences cannot be reduced to shared past economic events. How do these personal memories affect people’s beliefs and attitudes towards inflation beyond their common historical experience?

Individual memories affect beliefs beyond common historical experiences

After their inflation memories, we elicited the respondents’ views about inflation up to 2025, along with a range of other personal opinions and preferences. We employed econometric techniques to link detailed lifetime memories with inflation outlooks and policy-relevant beliefs, including trust in the central bank and awareness of its primary goal. Our comprehensive questionnaire controls for numerous potential confounders, and we incorporate historical inflation data to separate the influence of personal memories from collective experience.

Figure 1 Lifetime memories of inflation and disinflation episodes

a) Inflation versus disinflation experience

b) Reasons for inflation by decade

c) Reasons for disinflation by decade

Notes: Panel A shows the distribution of recalled inflation/disinflation episodes by year; Panels B and C break it down by decade and main reason reported.

We find that inflation and disinflation memories are correlated with inflation forecasts. Recalling past inflationary episodes is associated with a higher inflation outlook and more confidence in these outlooks. By contrast, the larger the disinflations recalled, the lower the inflation expectations. Interestingly, the largest effect on expectations is observed for disinflations that people attribute to policy. Recalling past disinflations is also associated with more uncertainty regarding future inflation, reflecting the fact that these people envision a broader set of possible future inflation outcomes. Additionally, we report clear evidence that inflation memories are closely tied to trust in the ECB. Recalling past increases in inflation is associated with less trust, recalling disinflationary episodes with more trust. We also find that memories of both inflation surges and disinflations are associated with a deeper knowledge about instruments and objectives of monetary policy.

An important policy-relevant takeaway from this analysis is that those who remember prior disinflations are more open to the possibility of future inflation declining sharply, such that they have lower inflation forecasts on average, consistent with more trust that the ECB will be successful in bringing inflation back to its target. Is it merely an association or do various inflation memories cause different inflation expectations? If so, can we artificially recreate lifetime memories of inflation to shift people’s expectations?

Creating pseudo-life experiences through games treatments

After eliciting their inflation expectations, some survey and lab participants were randomly chosen to play a game that consisted of repeatedly predicting next year’s inflation while incrementally observing inflation in the previous years. These ‘treated’ individuals played either with data from a rising inflation episode (1967–1975), a decreasing inflation episode (1980–1988), or a flat inflation episode (2006–2014), while the rest of the respondents skipped the game as they constituted the control group. We then elicited inflation expectations once more to explore how the game treatments may have affected the participants’ expectations, while accounting for their inflation priors and retrieved memories.

We find that playing the forecasting games can have powerful effects on expectations, both in the lab and in the survey, and these effects largely mirror those of inflation memories: playing through a period of rising inflation raises inflation expectations, whereas playing through an episode of flat or falling inflation tends to reduce inflation expectations. This latter treatment effect is larger for respondents who did not report any memory of inflation or who declared relatively higher prior beliefs about inflation. Interestingly, in a follow-up survey conducted months later, individuals were more likely to recall both inflation surges and disinflations if they had played a game with decreasing inflation in the first wave, with the effect of disinflations being particularly strong for young survey participants. Furthermore, consistent with the idea that forecasting games create new memories, we find that the effects of the game experience on inflation expectations persist in the follow-up survey, even after accounting for individuals’ prior memories.

Conclusion

Our results suggest that inflation memories at least partly cause inflation expectations, so the recent inflation surge could persistently affect household inflation expectations. How it does so, however, will depend on whether individuals’ memories focus more on the inflation increase or the ongoing disinflation, as the two affect expectations quite differently. Policy communication could play a role in shaping the future narrative that individuals will recall about current inflation dynamics (Wohlfart et al. 2023 emphasise the importance of narratives in shaping individual expectations). Delving further into how memories are formed and persist would allow for a better understanding of how a specific episode like the recent inflation surge is likely to affect economic expectations and the conduct of monetary policy in subsequent years. Graeber et al. (2023), for example, provide novel evidence on the formation of memories.

Our work also helps bridge the gap between the survey and the lab experimental literature: while lab subjects are young college students and do not share the longer life experiences of the broader population, our results suggest that game experience can partially recreate that life experience and help make them more representative of the broader population. Because laboratory experiments have many other advantages, the ability to make their participants more diverse could help expand the scope of questions that can be fruitfully addressed in the lab.

References

Braggion, F, F von Meyerinck, N Schaub and M Weber (2023), “The Long-term Effects of Inflation on Inflation Expectations”, manuscript.

Braggion, F, F von Meyerinck, N Schaub and M Weber (2023), “The Long-term Effects of Inflation on Inflation Expectations”, VoxEU.org, 13 September.

Graeber, T, C Roth and F Zimmermann (2023), “Stories, Statistics and Memory”, VoxEU.org, 9 February.

Kose, M A, F Ohnsorge and J Ha (2022), “Today’s inflation and the Great Inflation of the 1970s: Similarities and Differences”, VoxEU.org, 30 March.

Malmendier, U (2008), “‘Depression Babies’: do macroeconomic experiences affect risk-taking”, VoxTalk, 8 August.

Malmendier, U and S Nagel (2016), “Learning from Inflation Experiences”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 131(1): 53–87.

Malmendier, U and J A Wachter (2023), “Memory of Past Experiences and Economic Decisions”, Handbook of Human Memory, Oxford University Press, forthcoming.

Salle, I, Y Gorodnichenko and O Coibion (2023), “Lifetime Memories of Inflation: Evidence from Surveys and the Lab”, NBER working paper No. 31996, December.

Wohlfart, J, I Haaland, C Roth and P Andre (2023), “Inflation narratives”, VoxEU.org, 23 December.