Can a negative mood tank the economy? Recently, discussion about a ‘vibe-cession’, or an episode of negative sentiment that might cause poor economic performance, has gained prominence in the financial press (Scanlon 2022a, 2022b, Keynes 2023) and drawn serious attention from policymakers struggling to read contradictory macroeconomic signals (Federal Open Market Committee 2024).

The idea that emotional states may affect the economy has a long intellectual history. John Maynard Keynes regrettably missed his chance to coin ‘vibe-cession’, but he wrote extensively about how peoples’ instinctive ‘animal spirits’ drove crashes and recoveries. Taking this idea one step further, economist Robert Shiller has advocated for a more detailed study of economic narratives, or contagious stories that shape how individuals view the economy and make decisions. Viral narratives could be the missing link between emotions and economic fluctuations. But, as economic modellers, we currently lack effective tools to measure these narratives, model their possible impacts on the economy, and quantify their contribution toward economic events.

Our recent research (Flynn and Sastry 2024) makes a first attempt to understand the macroeconomic consequences of narratives. We introduce new tools for measuring and quantifying economic narratives and use these tools to assess narratives’ importance for the US business cycle.

Measuring narratives using natural language processing

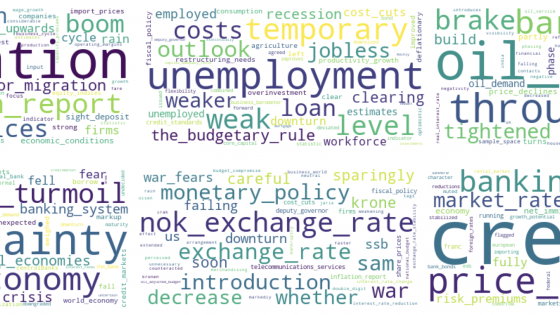

To measure narratives, we use resources not available to Keynes: large textual databases of what economic decisionmakers are saying and natural language-processing tools that can translate this text into hard data. Specifically, we study the text of US public firms’ SEC Form 10-K, a regulatory filing in which managers share “perspectives on [their] business results and what is driving them” (US Securities and Exchange Commission 2011), and their earnings report conference calls. We process these data using three methods designed to capture different facets of firms’ narratives: (i) a sentiment analysis; (ii) a textual similarity analysis that looks for connections to the “perennial economic narratives” that Shiller (2020) identifies as particularly influential in US history; and (iii) a fully algorithmic ‘latent dirichlet allocation’ model that looks for any repeating patterns in firms’ language. Using these methods, we obtain quantitative proxies for the narratives that firms use to explain their business outlook over time – for example, firms’ general optimism about the future, their excitement about artificial intelligence trends, or their adoption of new digital marketing techniques.

Narratives shape firms’ decisions and spread contagiously

In our data, we find that firms with more optimistic narratives tend to accelerate hiring and capital investment. This effect is above and beyond what would be predicted by firms’ productivity or recent financial success. Strikingly, firms with optimistic narratives do not see higher stock returns or profitability in the future and also make over-optimistic forecasts to investors. That is, firms’ optimistic and pessimistic narratives bear the hallmarks of Keynes’ ‘animal spirits’: forces that compel managers to expand or contract their business but do not predict future fundamentals.

We next find that narratives spread contagiously. That is, firms are more likely to adopt the narratives held by their peers, both at the aggregate level and within their industries. The narratives held by larger firms have an especially pronounced effect. Thus, consistent with Shiller’s hypothesis, narratives can spread like a virus: once some take a gloomy outlook in their reports or earnings calls, others follow suit.

Narratives drive about 20% of the business cycle

To interpret these results, and leverage them for quantification and prediction, we develop a macroeconomic model in which contagious narratives spread between firms. Because narratives are contagious, they naturally draw out economic fluctuations: even a transient, one-time shock to the economy can have long-lasting effects because a negative mood infects the population and holds back business activity. Sufficiently contagious narratives that cross a virality threshold can induce a phenomenon that we call narrative hysteresis, in which one-time shocks can move the economy into stable, self-fulfilling periods of optimism or pessimism. In these scenarios, there is a powerful positive feedback loop: economic performance feeds a narrative that reinforces the economic performance. These findings underscore the importance of measurement to discipline exactly how much narratives affect the economy.

Figure 1

Note: The dashed line plots the US business cycle from 1995 to 2018. The solid line, based on our analysis, is the contribution of contagious narratives toward business-cycle fluctuations. The shaded area is a 95% confidence interval based on statistical uncertainty in our estimates.

How strong are the narratives driving the US economy? Combining our empirical results with our theoretical model, we estimate that narratives explain about 20% of the US business cycle since 1995 (Figure 1). In particular, we estimate that narratives explain about 32% of the early 2000s recession and 18% of the Great Recession. This is consistent with the idea that contagious stories of technological optimism fuelled the 1990s Dot-Com Bubble and mid-2000s Housing Bubble, while contagious stories of collapse and despair led to the corresponding crashes. Our analysis, building up from the microeconomic measurements of firms’ narratives and decisions, allows us to quantify these forces.

When can economic narratives ‘go viral’?

Our findings suggest that optimistic narratives generate business cycles, but do not truly ‘go viral’ and generate narrative hysteresis. Figure 2 visualises this by showing how much narratives might have affected output if they were counterfactually more prone to virality. We focus on two key parameters disciplined by our measurement: the ‘stubbornness’ with which firms maintain existing narratives, and the ‘contagiousness’ with which narratives spread. Our main estimate, denoted with a large “x”, is far from the virality threshold we derive theoretically (denoted by a dashed line). If the narrative were associated with greater stubbornness or contagiousness, then narrative dynamics would be considerably more violent – potentially explaining almost all of the business cycle, in the most extreme calibrations.

Figure 2

Note: This figure illustrates the tendency of business-cycle narratives toward virality. The horizontal and vertical axis respectively denote measurable contagiousness (how much a narrative spreads) and stubbornness (how much proponents stick to their narrative). The “x” corresponds to our measurement for the main narrative affecting US business cycles, and the dots correspond to our measurements for more granular narratives. Selected narratives are labelled. The shading denotes how much of the business cycle the narrative explains for a given level of contagiousness and stubbornness. The dashed line denotes the theoretical virality threshold that determines whether narrative hysteresis is possible.

Does that mean that all economic narratives lead tranquil lives? Not necessarily. In further analysis, we study the spread and effect of more granular narratives picked up by our other natural language-processing analysis. These narratives are associated with higher stubbornness and virality and are therefore more prone to ‘going viral’ (as denoted by the small circles). Viewed from afar, the narratives in the US economy form a constellation whose stable behaviour on average belies more violent individual fluctuations. This is consistent with the idea that ‘vibe-cessions’ are slow-moving, but more specific fears and fads move quickly.

Policymaking in the narrative economy

Our analysis suggests that contagious narratives are an important driving force in the business cycle. But it also qualifies this conclusion in important ways. Not all narratives are equal in their potential to shape the economy, and the fate of a given narrative may rest heavily on its (intended or accidental) confluence with other narratives or economic events.

How should policymakers act in a narrative-driven economy? Our analysis has at least three major conclusions, which also suggest future directions for both academic and policy research.

First, what people say about their economic situation is highly informative about both individual attitudes and broader trends in the economy. Public regulatory filings and earnings calls already contain considerable information. Both policymakers and researchers can use improved machine-learning algorithms and data-processing tools to analyse this information. There are also possible implications for how researchers and governments collect information. The same data-science advancements have increased the value of novel surveys that allow households or businesses to explain the ‘why’ behind their attitudes and decisions (e.g. Wolfhart et al. 2021).

Second, some narratives are more influential and contagious than others. It is therefore important to combine descriptive studies measuring narratives with empirical analysis of their effects on decisions and their spread throughout populations.

Third, the narratives introduced by policymakers could be potentially very impactful. We know relatively little about what makes a policy narrative into a great story that spreads contagiously and affects the economy on its own. Understanding these dynamics is an important area for future research.

References

Flynn, J and K Sastry (2024), “The Macroeconomics of Narratives”, NBER Working Paper 32602.

Keynes, S (2023), “Are bad vibes holding back the British economy?”, Financial Times, 18 July.

Scanlon, K (2022a), “The Vibecession: The Self-fulfilling Prophecy”, 30 June.

Scanlon, K (2022b), “The vibes in the economy are…weird. Really weird,” New York Times, 4 August.

Federal Open Market Committee (2024), Transcript of Press Conference, 31 January. Accessed from:

Shiller, R (2020), Narrative Economics: How stories go viral and drive major economic events, Princeton University Press.

US Securities and Exchange Commission (2011), “How to read a 10-K”.

Wolfhart, J, I Haaland, C Roth, and P Andre (2021), “Inflation Narratives”, VoxEU.org, 23 December.