Economic theory suggests a number of economic benefits that may accrue to developing countries when they increase trade and exports, including wage growth. Many studies have shown that increasing trade can affect male and female labour market outcomes differently, however. As Yahmed and Bombarda (2018) discuss, for instance, trade liberalisation can lead to greater economy-wide formal job creation for men but not necessarily for women.

Apparel is an important sector to look at in terms of gender-differentiated labour market effects because it represents an important global tradable sector that is relatively high in female employment. Recent studies show increasing apparel exports improve a number of development outcomes for women; increasing apparel exports is linked to falling women’s work informality (Goutam et al. 2017), women marrying and having children later, and increasing female school enrolment and labour force participation in Bangladesh (Heath and Mobarak 2015).

Bangladesh: A test case for apparel trade liberalisation and wages

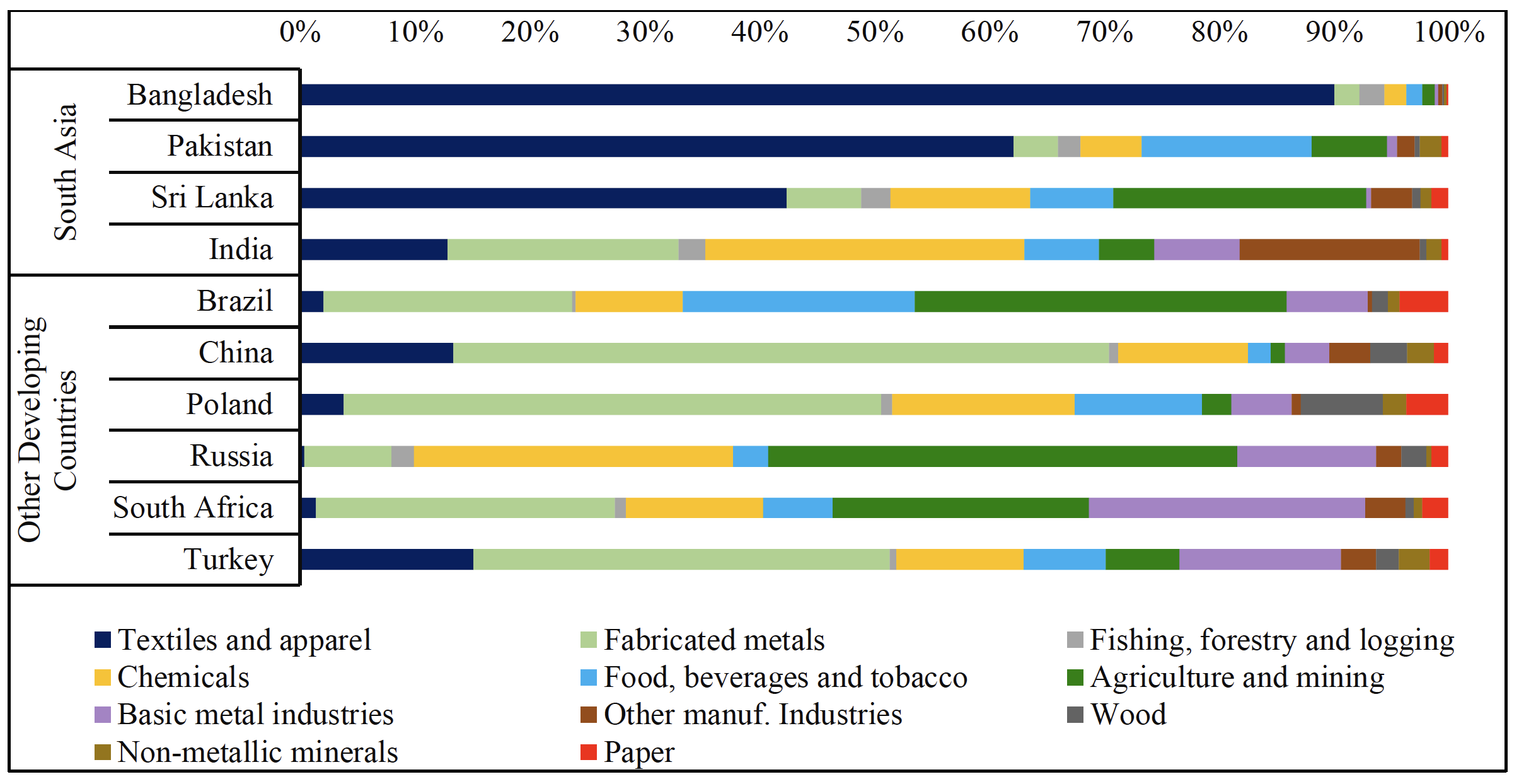

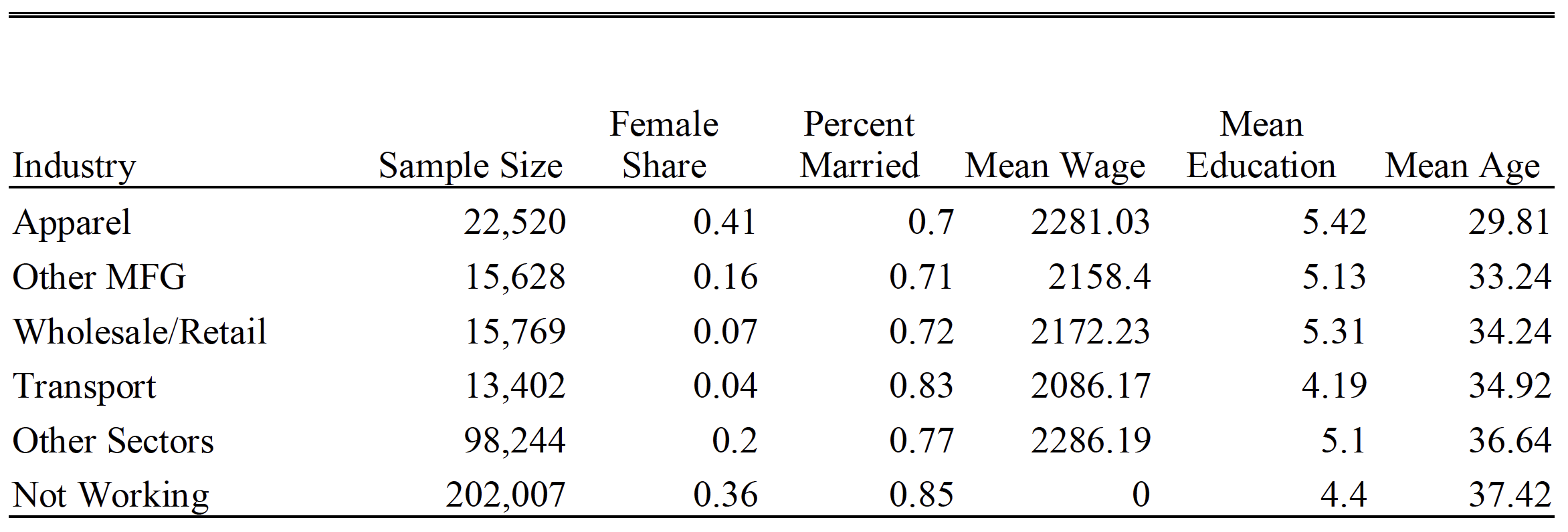

More than other countries, Bangladesh’s exports are concentrated in apparel (Figure 1), and are much more female labour-intensive than other economic sectors in Bangladesh (Table 1 shows that female share in “Apparel” employment is 41% compared to 16% for “Other Manufacturing”).

Like many developing countries, Bangladesh followed an ‘import-substitution-industrialisation’ strategy for much of the 20th century but began to implement liberalising reforms in the 1990s. The government reduced the maximum import duty of 350% in 1993 to 32.5% in 2003, and to 25% in 2005. Bangladesh also reduced the number of tariff bands from 15 in 1993 to 4 in 2016. Between 1992 and 2008, the unweighted average tariff rate declined from a high of 70% to a low of 12.3%. During the 1990s several measures reduced the cost of imported inputs, including reducing tariffs, subsidised interest rates on bank loans, cash subsidies, exemptions from value added and excise taxes, bonded warehouse facilities, a duty drawback facility, duty-free imports of machinery and inputs for export industries, an export credit guarantee scheme, and income tax rebates for exporters. The government established “Export Processing Zones” that included basic factory structures with dependable utilities, secured industrial areas, central monitoring of labour compliance, and one-stop facilities for exports. When the dust from the reforms settled, apparel emerged as the dominant export industry.

Figure 1 Bangladesh exports by sector 2016

Notes: Sectorial breakdown of country-wise exports from South Asia and other developing countries, 2016 (%).

Source: Artuç et al., (2019).

Table 1 Summary labour market statistics, Bangladesh

Note: Authors’ elaboration using the combines labor forced surveys from 2005, 2010, 2013, and 2016.

A great deal of COVID-19-related support to developing countries like Bangladesh focused on apparel and maintaining jobs in the sector. Woodruff (2020) argues that whether the COVID-19 health crisis would escalate into a humanitarian crisis or not depended “crucially on decisions of foreign apparel buyers to honour previously agreed orders”—that is, whether the country would continue to export high volumes of apparel.

Since Bangladesh primarily exports apparel, it offers the opportunity to study whether exporting in a particular industry generates benefits that go beyond the exporting sector and to what extent this affects male and female wages differently. Studies have shown that trade can affect wages of men and women differently because they affect specific industries (Olivetti and Petrongolo 2014, Sauré and Zoabi 2014), specific regions (Hakobyan and McLaren 2016), and the ability to discriminate due to market competition (Berik et al. 2004, Menon and Rodgers 2009).

Applying models that look at men and women as different factors of production

Trade theory offers helpful guidance to understand how exports might affect wages. Heterogenous Firm Comparative Advantage (HFCA) models (Bernard et al. 2007, Lechthaler and Mileva 2019)—two-sector, two-factor models—show how trade liberalisation affects the wages of the two factors in the short run and long run by shifting demand between industries unequally across factors. The HFCA models show how an increase in the output price (as opposed to quantities or export values) of the exported good affect wages in the export sector in the short run but, in the long-run, the wage effects become factor-specific. Specifically, these models show that wages increase in the exporting sector for both men and women in the short run, but over time shift to reward the factor intensively employed in the export sector, regardless of the sector in which those workers are employed. In our case, the prediction is that the increase in apparel prices increases male and female wages in the apparel sector in the short run, but eventually the effects dissipate to reward females relative to males throughout the economy—that is, increasing apparel exports and prices decreases the wage gap between men and women economy wide.

Three conditions are necessary for the HFCA model to apply:

- Factor intensity of the export industry is different from other industries.

- The two factors – males and females – must be imperfect production substitutes.

- Workers are relatively mobile throughout the country

We evaluate the conditions required for the HFCA models to apply in our Bangladesh context. We use household surveys

to show that apparel is a female-intensive industry, that males and females are imperfect substitutes in production, and that labour markets in Bangladesh are relatively integrated, that is, migration is possible to the extent that it makes labour mobile across the country. Further, we look at Bangladesh apparel exports at a time when policy changes in the EU corresponded to an increase in apparel-export unit prices

of about 20% between 2010 and 2013. We illustrate average wage differences and trends in Bangladesh before and after the change in the EU policy and use trade data to calculate unit values for both knit and woven apparel to demonstrate the change in average export prices that followed the policy change.

Conclusions: increasing apparel exports narrows the economy-wide male-to-female wage gap

Overall, we find our results to be consistent with the predictions of HFCA models. When defining males and females as two different factors of production, the changes in wages that follow the policy change are factor-specific rather than industry-specific in three to five years. Our analysis shows that the policy change coincided with a significant drop in the male-female wage gap that was not specific to the apparel industry. Our results reveal a positive relationship between exports and wages for less-educated females, but these are not significant for apparel workers generally or for less-educated males. Our results are similar to Robertson (2004) who finds that the factor-specific (as opposed to industry-specific) effects of price shocks emerge in three to five years. There is little evidence of industry-specific effects over the three-year timeframe we use in our empirical work.

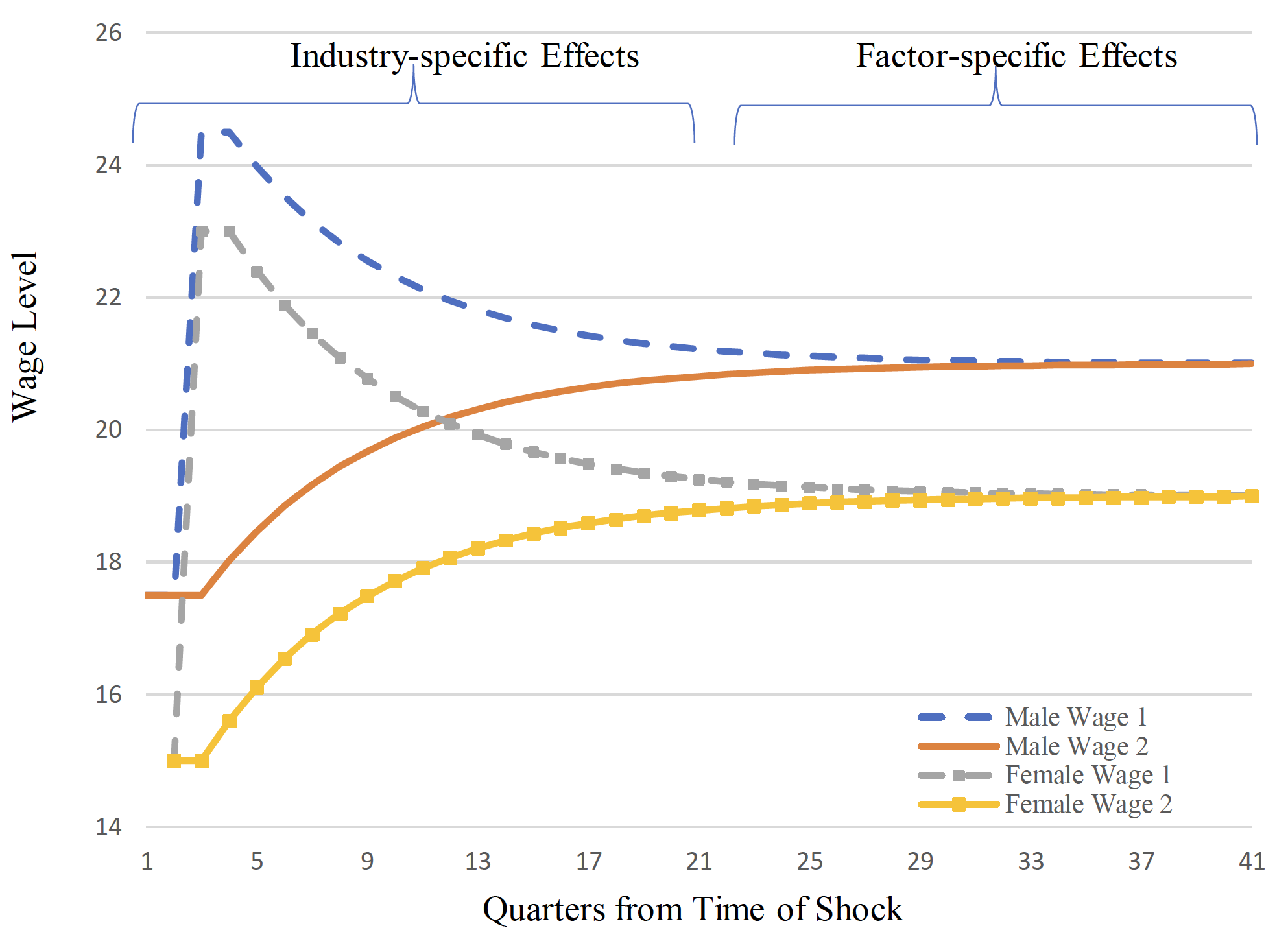

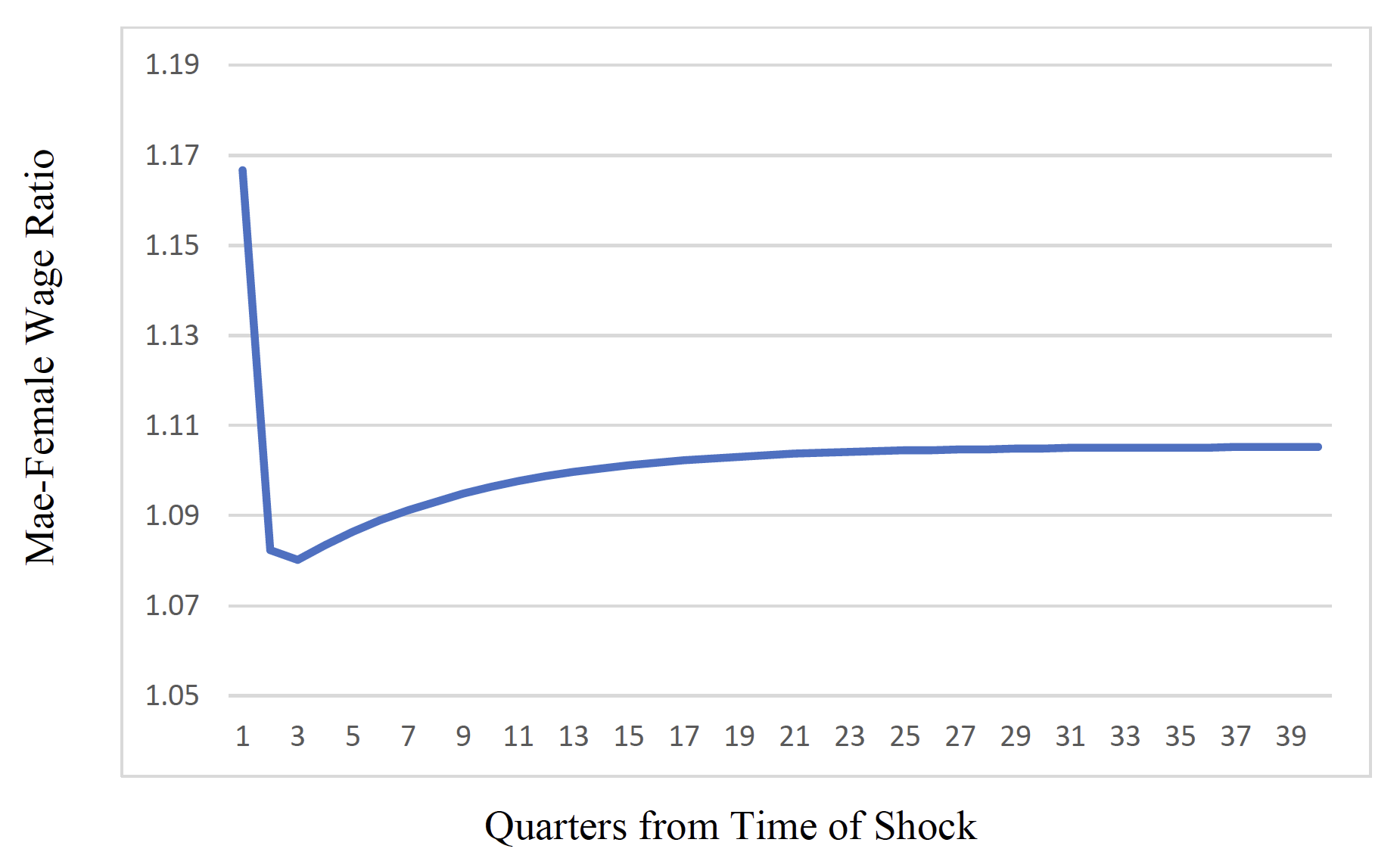

Based on our data analysis, Figure 2a shows the evolution of four series: male wages in sector 1, male wages in sector 2, female wages in sector 1, and female wages in sector 2. Figure 2b shows that, in our simulation, the 20% increase in the exported-good final price is associated with a fall in the economy-wide male-female wage gap from 1.167 to 1.108, a decline of about 5%. In our simulation, the industry-specific effects dissipate, and the factor-specific results emerge at around 20 quarters (5 years).

Figure 2a Dynamic wage adjustment in HFCA models

Notes: This figure shows the effects of a 20% relative price shock to industry 1. Using alpha values of 0.6 and 0.4, the initial equilibrium wage is 17.5 for males and 15 for females. The final wage is 21 for males and 19 for females. The Male Female wage gap falls from 1.167 to 1.105 (see figure 1b). Time periods (quarters) are shown along the horizontal axis and the shock occurs in period 1.

Figure 2b Dynamic adjustment of aggregate male-female wage ratio

Notes: This figure shows the effects of a 20% relative price shock to industry 1. See Figure 1a for details. The Male-Female wage gap falls from 1.167 to 1.105. Time periods (quarters) are shown along the horizontal axis and the shock occurs in period 1.

Our study may be limited in several ways. First, Bangladesh is one of a very small group of countries whose exports heavily concentrate in apparel. Thus, the two-sector, two-factor heterogeneous firm comparative advantage may be less applicable for more diversified economies. Second, Bangladesh seems to enjoy a more integrated domestic labour market compared to many developing countries, while other studies find very high regional labour-market segmentation. Nevertheless, Bangladesh remains an important and highly visible apparel-exporting developing country and our results suggest that Bangladeshi women in particular have experienced rising earnings economy-wide through increasing apparel exports and connections to global value chains.

References

Artuc, E, G Lopez-Acevedo, R Robertson and D Samaan (2019), Exports to Jobs: Boosting the Gains from Trade in South Asia, Washington, DC: World Bank.

Berik, G, Y Rodgers and J Zveglich, Jr (2004) “International Trade and Gender Wage Discrimination: Evidence from East Asia”, Review of Development Economics 8: 237- 254.

Bernard, A B, S J Redding and P K Schott (2007), “Comparative Advantage and Heterogeneous Firms”, The Review of Economic Studies 74(1): 31-66.

Goutam, P, I A Gutierrez, K B Kumar and S Nataraj (2017), “Does Informal Employment Respond to Growth Opportunities? Trade-Based Evidence from Bangladesh”, Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.

Hakobyan, S and J McLaren (2016), “Looking for Local Labor Market Effects of NAFTA”, Review of Economics and Statistics 98(4): 728–41.

Heath, R and A M Mobarak (2015), “Manufacturing growth and the lives of Bangladeshi women”, Journal of Development Economics 115(C):1-15.

Lechthaler, W and M Mileva (2019), “Trade liberalization and wage inequality: new insights from a dynamic trade model with heterogeneous firms and comparative advantage”, Review of World Economics 155: 407–457

Menon, N and Y Rodgers (2009), “International Trade and the Gender Wage Gap: New Evidence from India's Manufacturing Sector”, World Development 37(5): 965-981.

Olivetti, C and B Petrongolo (2014), “Gender Gaps Across Countries and Skills: Demand, Supply, and the Industry Structure”, Working Paper.

Robertson, R (2004), “Relative Prices and Wage Inequality: Evidence from Mexico”, Journal of International Economics 64(2): 387-409.

Sauré, P and H Zoabi (2014), “International trade, the gender wage gap and female labor force participation”, Journal of Development Economics 111(C):17-33.

Woodruff, C (2020), “Buyer responsibility and the growing crisis in Bangladesh”, VoxEU.org, 30 April.

Yahmed, S B and P Bombarda (2018), “Gender, informal employment, and trade liberalisation in Mexico”, VoxEU.org, 24 June.