Epidemiologists, economists, and policymakers continue to devote considerable attention to forecasting the human ravages and economic toll of COVID-19 (Baldwin and Weder di Mauro 2020a, 2020b). We provide a global view of the economic impact of COVID-19, retrospective and prospective, by examining the immediate effects and bounce-back from six post-war disease crises: the 1968 Flu (aka Hong Kong Flu), SARS (2003), H1N1 (2009), MERS (2012), Ebola (2014), and Zika (2016). The data indicates that GDP growth contractions are immediate and sizeable, with some affected countries experiencing larger drops than others. Bounce-back in GDP growth is immediate, but GDP is still below pre-shock levels five years later. The negative effect on GDP is felt less in countries with larger first-year responses in government spending, especially on health care. International trade plummets. The indirect effects on GDP growth from affected trading partners are non-trivial, for both the initial GDP growth decline and the positive bounce-back.

Health crisis severity

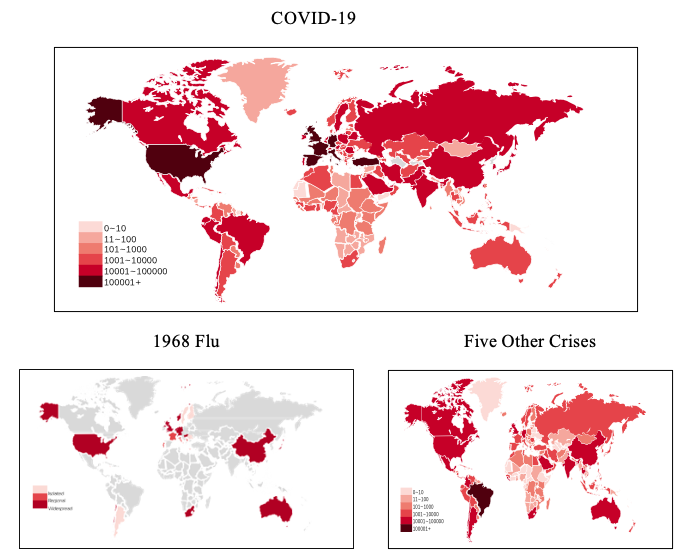

Figure 1 depicts the global severity of the health crisis episodes under investigation. It displays the number of cases, respectively, for: (i) the 1968 Flu (for which reliable case data by country is unavailable), (ii) the sum of the other five crises, and (iii) COVID-19 (as of 28 April 2020). Although the ongoing crisis stands out for its severity, other episodes were also large. For example, 500,000 infections were estimated to have occurred in Hong Kong in the first two weeks of the 1968 Flu.

Figure 1 Severity of COVID-19 and six other modern health crises

Distribution of GDP growth around health crises

A summary of the relationship between these health crises and real GDP growth for our sample of 210 countries can be seen in Figure 2. The data are from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators.

Figure 2 GDP growth rate distribution

In the upper left panel, we depict the distribution of GDP growth in all country-years other than the health crisis episodes. The upper right panel is the equivalent for the affected countries in the year in which the crisis was officially declared (noted above). The lower left and right panels depict the GDP growth distribution for those same countries in the year immediately following the crisis. Average GDP growth for the non-disease sample is 3.83%. For affected countries, the average is 1.44% in the onset year, and 3.98% in the following year. We also depict the location of Finland, the US, and China. Of the six crises, these countries were affected in two, six, and three episodes, respectively. The lower left panel suggests that bounce-back in GDP growth is relatively rapid and robust on average for affected countries. It is also clear from this figure that countries have different experiences. Growth in China continues practically unabated through the crises episodes. Finland and the US are essentially on top of each other in non-Crisis years and in bounce-back years, but a gap opens between them during crisis years.

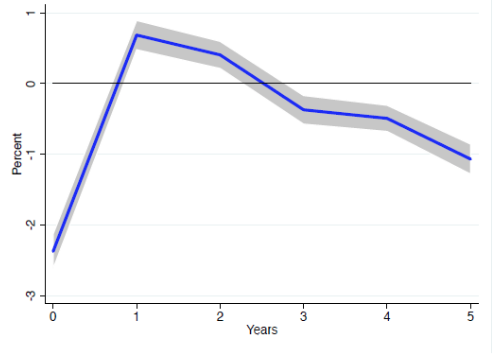

GDP growth following a health crisis shock

In Figure 3, we display estimates from a well-known econometric procedure, local projections (Jorda 1985), to evaluate the path of GDP in affected countries relative to unaffected countries. We display estimates for the crisis onset year and for the subsequent five years. On average, GDP growth in affected countries is about 2.4% below that of unaffected countries in the onset year.1 Bounce-back from health crises shocks appears quickly, according to our estimates, with affected countries enjoying nearly a one percentage point higher growth rate than unaffected countries in the year following the crisis.2 However, resumption in growth in affected countries is not sufficient to overcome the initial decline, leaving the level of GDP persistently lower in affected countries compared to unaffected countries.

Figure 3 Effect of health crises on GDP growth

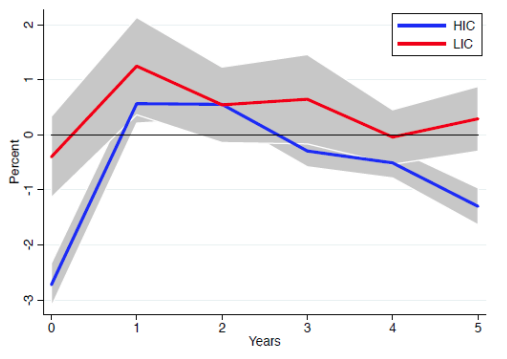

Effect on high-income and low-income countries

In Figure 4, we display estimates of the effect of health crises separately on high-income countries (in blue) and low-income countries (red), as classified by the World Bank. High-income countries affected by the crisis have a GDP growth rate in the onset year that is 3% less than the GDP growth for high-income countries unaffected by the crises. However, bounce-back for these affected high-income countries is quick, as seen by the fact that growth is nearly 1% higher in affected countries in the year after the crisis was declared. According to the red line in the figure, affected low-income countries have GDP growth rates that are not significantly different from unaffected low-income countries. Note that these are within-group comparisons, and hence do not speak to the issue of whether high-income or low-income countries are more affected by health crises.3

Figure 4 Effect of health crises on GDP growth of high-income vs low-income countries

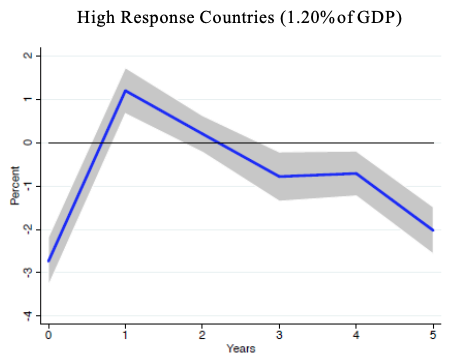

Fiscal policy works, especially government expenditures on health

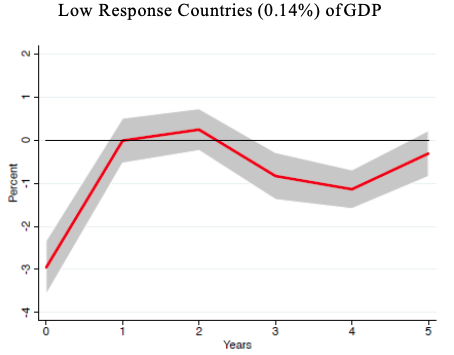

In response to COVID-19, finance ministries have undertaken a variety of spending and tax-related policies designed to support households and businesses, hoping to soften the impact of the crisis on economic activity. In Figure 5, we analyse the effects of government spending on healthcare policies during past crises. We divide countries according to their government’s adjustment in the onset year on healthcare spending, defined by the World Bank as “including healthcare goods and services consumed but not including capital health expenditures such as buildings, machinery, IT and stocks of vaccines for emergency or outbreaks”. High-adjustment countries (taken as the 75th percentile and above) are those that increased spending by an average of 1.2% of prior-year GDP. This is approximately the initial amount of total new US fiscal spending in response to COVID-19. Low-adjustment countries (taken at the 25th percentile and below) had onset-year spending increases of 0.14% of prior-year GDP, on average. We re-estimate the local projections model for GDP growth on high- and low-adjustment countries separately. Both groups experience large impact declines in GDP growth. However, high-expenditure countries bounce back more robustly (top panel) than low adjustment countries (bottom panel), suggesting the positive role of fiscal policy in crisis response.4

Figure 5 GDP growth response conditional on government expenditures on health

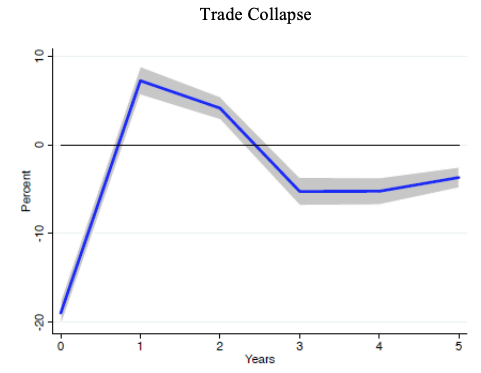

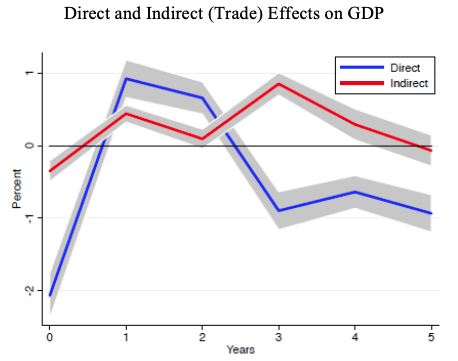

International trade elements

Finally, we consider international trade aspects of past health crisis episodes. First, we estimate the effect of the crises on the growth rate of international trade, measured as each country’s multilateral exports plus imports. We use the same local projections estimator. As seen in the top panel of Figure 6, international trade plummets, falling to a level that is on par with the US trade collapse in 2008-09 (Levchenko et al. 2010, Baldwin 2020), but rebounds quickly. Second, in the bottom panel, we decompose the overall effects of crises on GDP growth into direct and indirect effects that are due to feedback from a trading partner being affected. As seen in the figure, indirect effects are not trivial, contributing around -0.3% to GDP growth in the onset year (versus direct effects of -2.1%), and +0.4% in the bounce-back year (approximately half the magnitude of the recovery’s direct effect).

Figure 6 Health crises and international trade

Summary

The estimates presented in this column are highly likely to be a lower bound for the effect of COVID-19 globally. COVID-19 is more widespread than the average crisis in our sample. It may turn out to have a higher mortality rate as well. Existing global travel bans, social distancing, and economic lockdowns are unparalleled phenomena. Global value chains in production are also more prevalent, suggesting that countries will go down (and perhaps rebound) more sharply than in the past. According to initial data releases, GDP growth in 2020Q1 in China, the US, and euro area were -6.8%, -4.8%, and -14.5%, respectively, while US unemployment was 14.7% in April 2020. All are early signs that COVID-19 will indeed be worse. Nevertheless, massive interventions on the part of central banks and fiscal policymakers (of the type we find helps to speed up recovery) are now being undertaken worldwide. The eagerness of many policymakers to ‘re-open the economy’ notwithstanding, a restoration of robust international trade linkages remains an open question. Ominous signs of a backlash against China already appear from policymakers and in the media. The sentiment for countries not to be so reliant on imports, especially in sensitive sectors like medical supplies, may well prove an intractable foe for trade.

Authors’ note: The views in this column are solely the responsibility of the authors and should not be interpreted as reflecting the views of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System or of any other person associated with the Federal Reserve System.

References

Baldwin, R (2020), “The Greater Trade Collapse of 2020: Learnings from the 2008-09 Great Trade Collapse”, VoxEU.org, 07 April.

Baldwin, R and B Weder di Mauro (2020a), Economics in the Time of COVID-19, VoxEU.org eBook, CEPR Press.

Baldwin, R and B Weder di Mauro (2020), Mitigating the COVID Economic Crisis: Act Fast and Do Whatever It Takes, VoxEU.org eBook, CEPR Press.

IMF (2020), World Economic Outlook, April.

Jorda, O (2005), “Estimation and inference of impulse responses by local projections”, American Economic Review 95 (1): 161-182.

Levchenko, A A, L T Lewis and L L Tesar (2010), “The collapse of international trade during the 2008–09 crisis: in search of the smoking gun”, IMF Economic Review 58: 214-253.

Ma, C, J Rogers and S Zhou (2020), “Global Economic and Financial Effects of Modern Pandemics and Epidemics”, working paper.

Endnotes

1 Against this, note that the IMF forecasts -3% world GDP growth for 2020, down sizably from actual growth of +1.9% in 2019 (World Economic Outlook, April 2020).

2 The IMF forecasts a healthy recovery of 5.8% in world GDP growth in 2021.

3 The IMF growth forecasts for Low Income Developing countries is 0.4% in 2020, down from 5.1% in 2019. This compares to a forecast of -6.1% in 2020 for Advanced Economies. The IMF projects a rebound to 5.6% for the low income countries in 2021.

4 We also find that the effects of total government spending are very similar to the results depicted for health care expenditures (https://cepr.org/sites/default/files/news/CovidEconomics5.pdf).