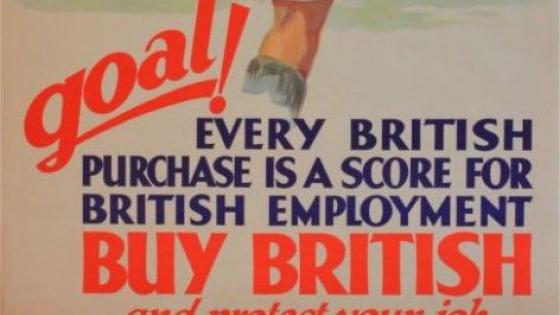

National identity has been a key fixture of the political discourse in many countries in recent decades (Colantone and Stanig 2017), with real policy implications such as the tightening of borders to immigration (Baldwin 2018) and trade (Evenett and Fritz 2019). There is growing evidence of how the media has played an important role in reinforcing these trends (Couttenier et al. 2019). But how far-reaching are these forces of national identity? Social psychologists have long discussed the pervasiveness of ‘banal forms of nationalism’ (Billig 1995) – but can they really affect even routine, day-to-day economic choices?

To answer this question, we take advantage of a plausibly unexpected political outcome that shifted the salience of British identity across the UK – the Brexit referendum leading to the collective decision for the UK to exit the EU – and the media storms that kept discussions about national identity top of mind (Sequeira and Nardotto 2021). We measure how moving the salience of national identity through media changed consumers’ purchases of UK versus EU products in a major UK retail grocery chain, up to nine months following the referendum.

Identity and grocery shopping: Key findings

Grocery shopping is an ideal setting to measure the day-to-day economic consequences of changes in the salience of national identity, given the frequency and representativeness of shopping transactions (Pandya 2016, Atkin 2019, Bertrand and Kamenica 2018). The measure allows us to observe real-time changes in economic behaviour at scale that are associated with well-defined media events.

We use scanner data from a major UK retailer – with hundreds of stores across the UK and 12 million customers who shop regularly with a loyalty card – to observe patterns of consumption of UK and EU products. The loyalty-card scheme allows us to compare purchases by the same consumers between March 2015 and March 2017, which spans 15 months before and nine months after June 2016, the date of the referendum. We also take advantage of the fact that during the nine months following the referendum, prices of EU and UK products were stable and their availability on the shelf did not change.

To quantify the impact of national identity on consumption, we focus on a set of products that were saliently labelled as being British, either because they had the Union Jack on the front of the package or because they had a British identifier in the product name such as ‘British cheddar’ or ‘English tea’.

We find that in the nine months following the referendum, products that were saliently labelled as being British experienced a 6% increase in sales relative to UK products without a flag and a 13% increase in sales relative to EU products. In the aggregate, across all stores, this corresponds to an approximate revenue increase for these products of over £194 million. Localities with a higher share of votes for the UK to leave the EU experienced stronger shifts towards UK products.

While there was a clear home bias, with shoppers replacing EU products with similar UK products, we do not observe large shifts in taste whereby consumers become more likely to buy quintessentially British products, such as Scottish oats or shortbread biscuits. We do however find that shoppers were more likely to shift towards UK products in areas with a larger share of immigrants.

The media: Keeping identity on tap

To understand the role of the media in making national identity salient, we obtain the universe of Brexit-related tweets published on Twitter in the UK between March 2015 and March 2017. We combine text analysis with machine learning to measure the direction of sentiment towards Brexit in each tweet. This allows us to identify a series of Twitter storms, i.e. weeks in which there are intense discussions about Brexit in the Twittersphere, and to identify these storms as primarily focusing on one of the following Brexit issues: economics, politics of regaining sovereignty, or immigration.

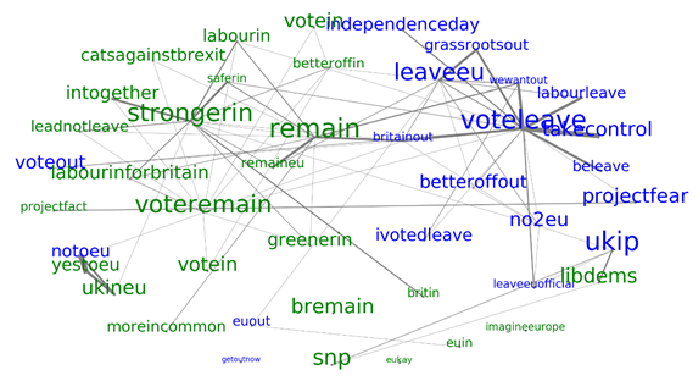

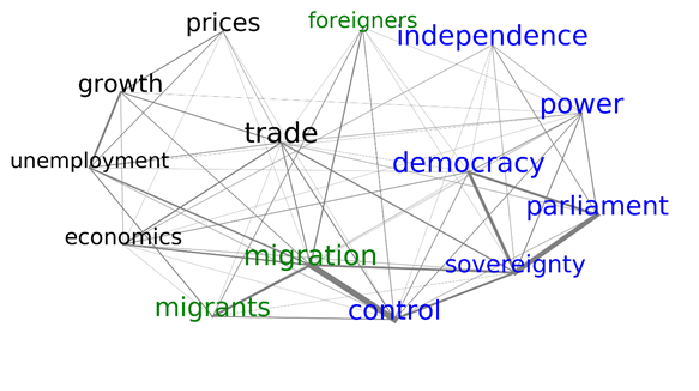

Figure 1 Word clouds representing the frequency of terms used in our sample of tweets

(a) Tweet content in favour of or against Brexit

(b) Tweet content on immigration, economics, and politics of regaining independence

Notes: In panel (a), green is tweet content in favour of Brexit, and blue, against Brexit. In panel (b), green is tweet content on immigration, black on the economics of Brexit, and blue on the politics of gaining independence.

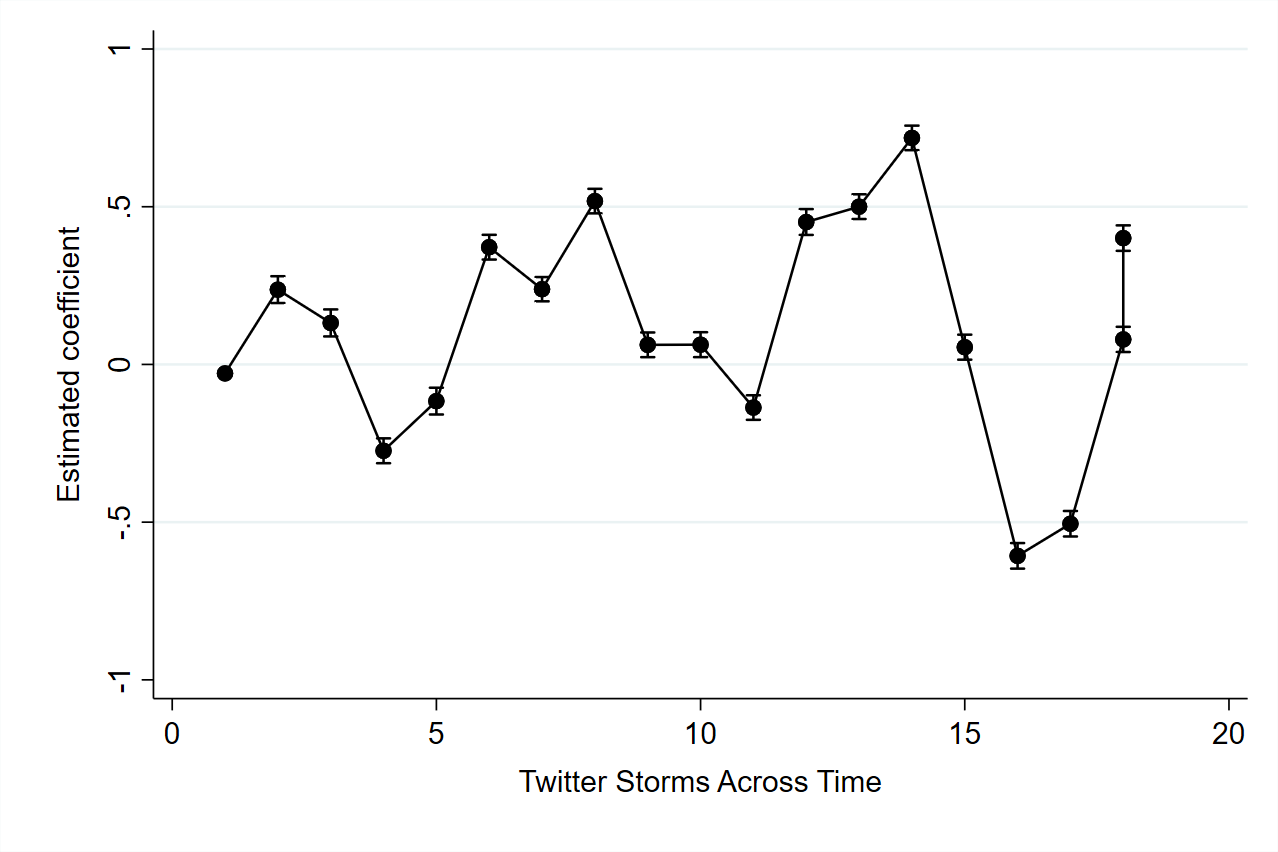

We find that weeks in which the Twitter world is alight with conversations in favour of Brexit – mostly debating the politics of regaining sovereignty – are the weeks in which sales of UK products grow. An increase of one standard deviation in the number of tweets (on average, an increase of 8,924 additional tweets per week) is associated with a 0.3% increase in the share of UK products purchased in a given store.

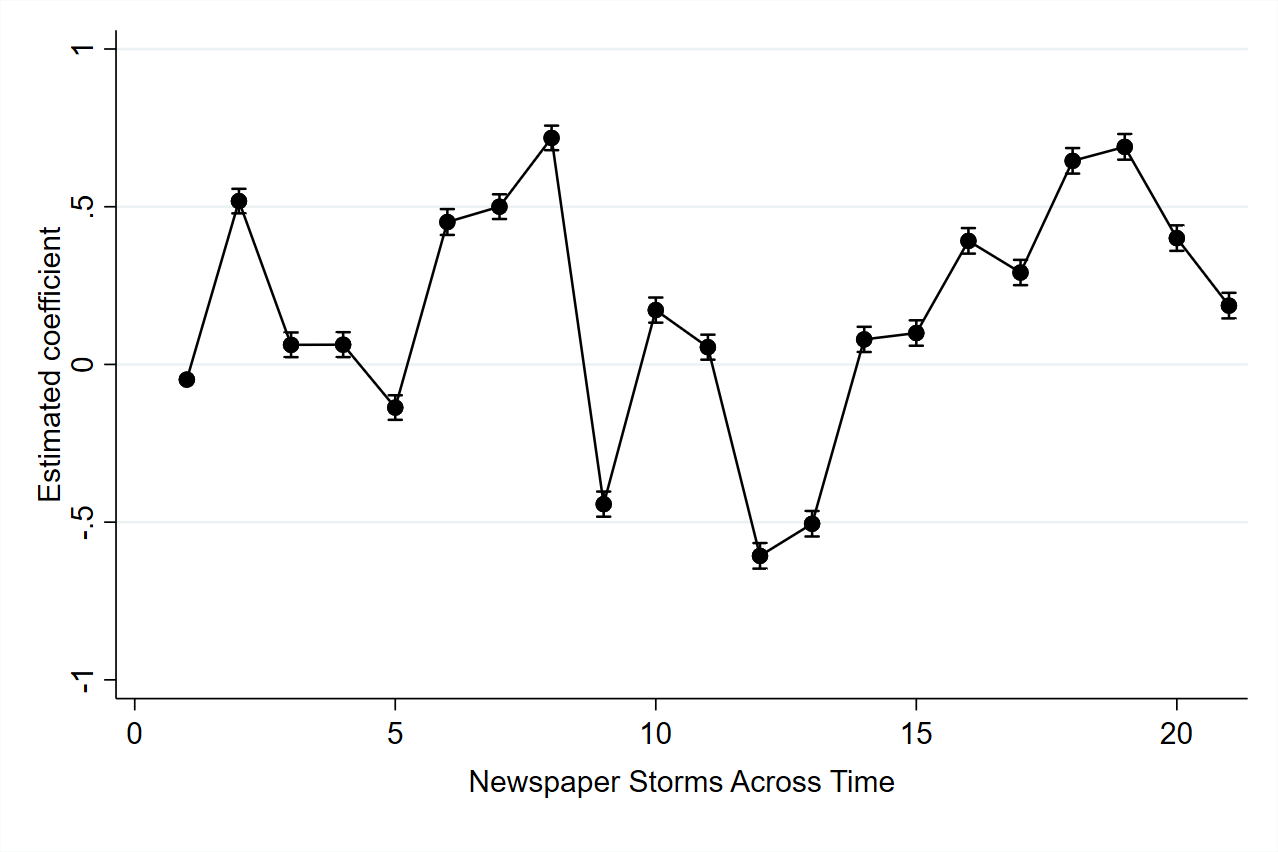

Since newspapers may have a wider reach than Twitter, as a second measure of media effects we also collate the universe of articles and headlines published on Brexit between March 2015 and March 2017, from a representative sample of UK newspapers. An increase of roughly 200 articles and headlines about Brexit in a given week is associated with a 0.4% increase in the purchase of UK goods.

The impact of media storms, despite some volatility, persists up to the end of our period of analysis, 9 months after the referendum took place.

Figure 2 Effect of media storms on increasing the consumption of UK products

(a) Effect of Twitter storms across time

(b) Effect of newspaper storms across time, relative to total number of storms between March 2015 and March 2017

Taken together, these results suggest that the media can play an important role in making identity salient to a large segment of the population and that this can spontaneously and intermittently affect routine economic behaviour.

Implications

Our work shows that identity preferences can matter broadly, even in socially remote settings characterised by limited social pressure to engage in a given behaviour. In fact, we conducted an online survey of over 1,000 UK shoppers in 2018, which revealed that 96% of respondents had felt no social pressure to buy more British products after the referendum.

These findings document and quantify the economic effects of a hidden form of ‘banal’ nationalism (Billig 2005). As habits are formed and supply chains adjust, these nationalist trends may be reinforced through a higher availability of UK products in the future. But our analysis also underscores the central role played by the media in this process: by amplifying political discussions and events, the media helps bring latent identity preferences to the fore and keep identity intermittently top of mind during routine economic decisions. This turning on and off of identity preferences can then lead to significant volatility in consumer choices.

More broadly, these insights are likely to apply to how the media affects similar behaviours through advertising or political campaigning. Repeated priming may persuade consumers or voters – but only when it activates a clear identity that then places certain behaviours top of mind.

References

Atkin, D, E Colson-Sihra, and M Shayo (2019), “How do we choose our identity? A revealed preference approach using food consumption”, Journal of Political Economy 129(4).

Baldwin, R (2018), “A new eBook: Brexit beckons”, VoxEU.org, 20 February.

Bertrand, M, and E Kamenica (2018), “Coming apart? Cultural distances in the United States over time”, CEPR Discussion Paper DP13024.

Billig, M (1995), Banal nationalism, Sage.

Colantone, I, and P Stanig (2017), “Globalization and economic nationalism”, VoxEU.org, 20 February.

Couttenier, M, S Hatte, M Thoenig, and S Vlachos (2019), “The media coverage of immigrant criminality: From scapegoating to populism”, VoxEU.org, 2 April.

Evenett, S, and J Fritz (2019), “Trade policy after three years of populism”, VoxEU.org, 23 December.

Pandya, S, and R Venkatesan (2016), “French roast: International conflict and consumer boycotts: Evidence from supermarket scanner data”, Review of Economics and Statistics 98(1): 42–5.

Sequeira, S, and M Nardotto (2021), “Identity, media and consumer behavior”, CEPR Discussion Paper DP15765.