Since the 2000s, the world has seen two major recessions: the Global Crisis of 2008-2009 and the Great Lockdown of 2020-2021. As a response, governments worldwide have increased spending to unprecedented levels. To illustrate the surge in fiscal expenditure, global debt at the turn of the century was $84 trillion, reached close to $170 trillion at the time of the 2008 financial crisis, and crossed the $300 trillion mark in 2022, according to the IMF Global Debt Database. In 2020 alone (the onset of the pandemic), global debt increased by 28 percentage points.

However, fiscal expansions are sometimes seen through an overly optimistic lens. Advocates argue that they stimulate economic activity, scaled up by potential multipliers. Ideally, with enough economic growth, the debt-to-GDP ratio can gear towards a downward path. However, much depends on the size of the fiscal multipliers (Alesina and Ardagna 2010, Ramey 2018).

In turn, critics highlight the dampening effects of lower investment, which in the literature is referred to as the crowding-out effect on firm lending (Brancati et al. 2018). The logic is as follows: when governments borrow, usually conducting large issuances of sovereign bonds, they compete with limited sources of available savings. As a result, real interest rates go up and private investment goes down.

More specifically, in a recent paper (Önder et al. 2023), we show that higher interest rates reduce the demand for corporate loans (used to produce capital goods), which in turn lowers investment, and through a contractionary effect in banks’ balance sheets, there is a sharp credit crunch in the economy. We show that this chain of events also feeds into the entire economy by lowering wages and discouraging labour supply, all of which leads to a decline in household consumption. In our empirical exercises, we not only confirm the existence of a crowding-out channel but also show that it is more pronounced during episodes of high government debt.

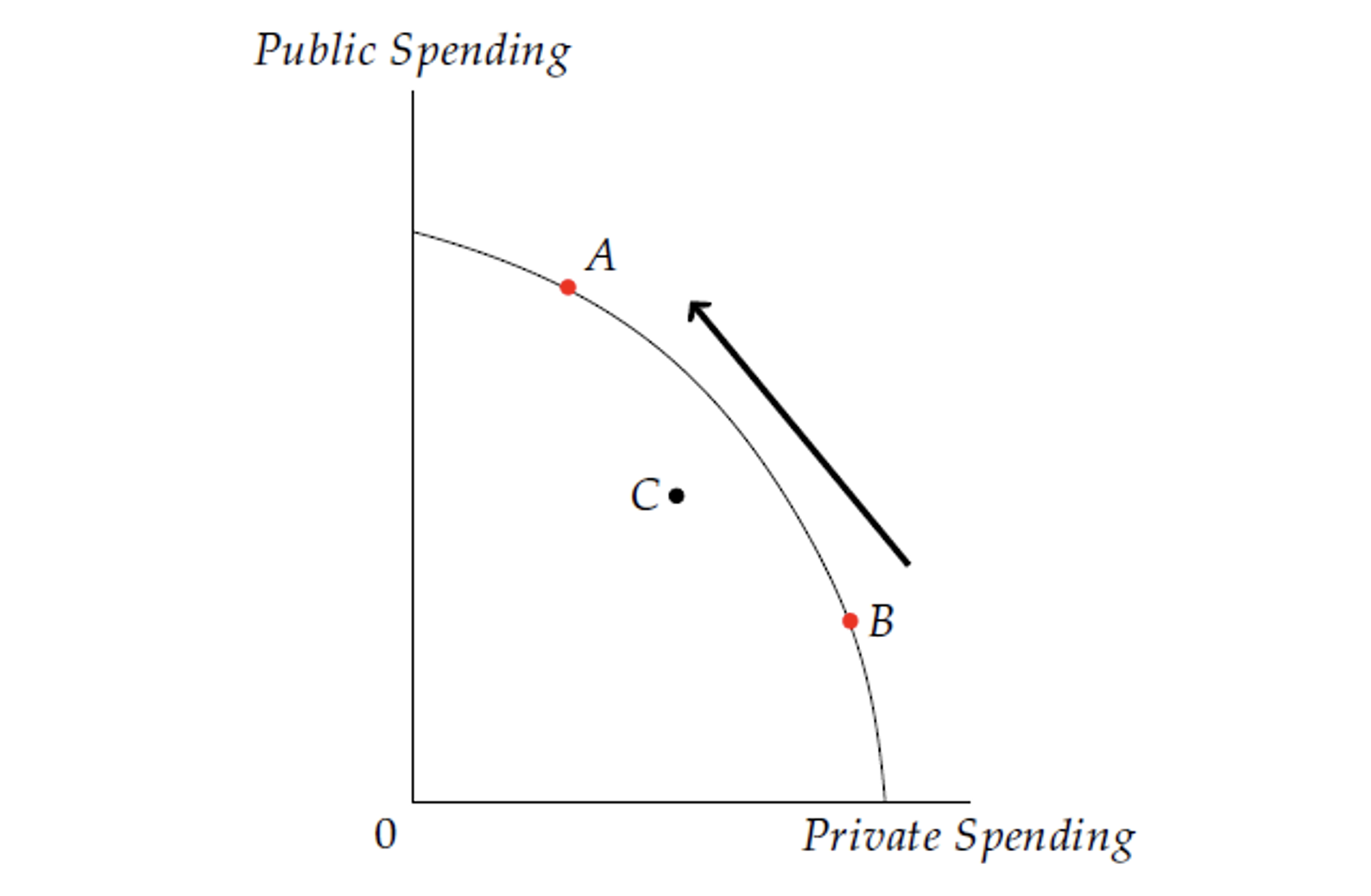

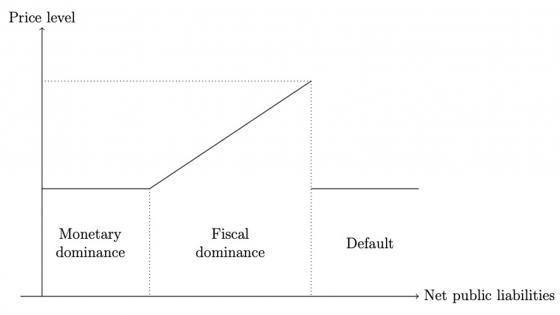

To date, with many countries holding record-high debt, fiscal policy – and its effects on the real sector – is at the forefront of macroeconomic debates. Importantly, not all government expenditures lead to a crowding out of lending. For illustrational purposes, consider the production possibilities curve depicted in Figure 1. A movement from point B to A reflects the case where government spending fails to boost aggregate demand due to a similar fall in private sector spending (investment). However, if the economy is below its full capacity (point C), the increased spending does not necessarily lead to a crowding-out effect on lending. Woodford (1990), for example, argues that higher public debt can actually increase investment by “reducing the extent to which people with access to productive investment opportunities are liquidity constrained”.

Figure 1 The production possibilities curve

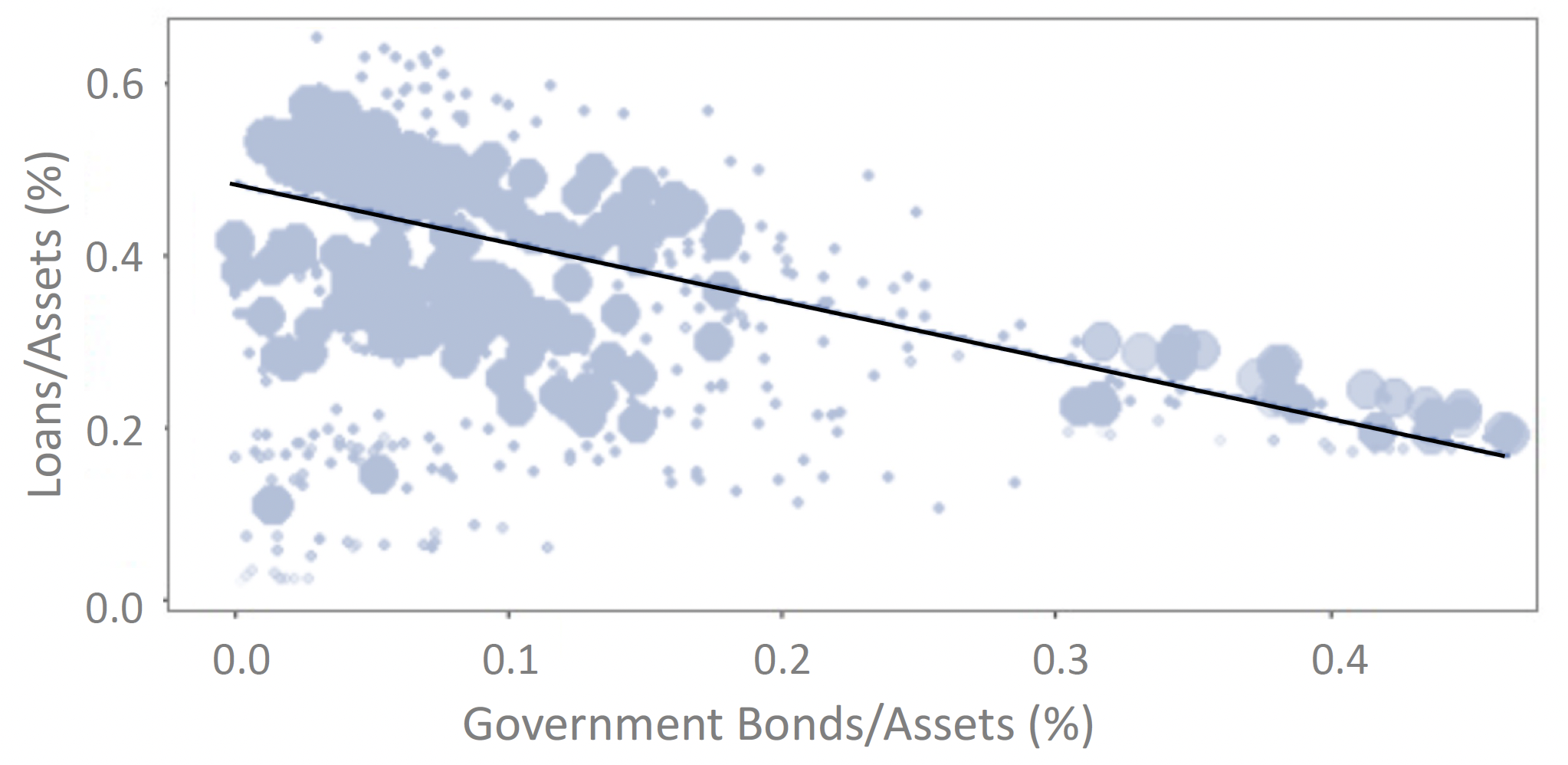

Figure 2 Banks’ take-up of government bonds and loan portfolio

Note: The figures are from Önder et al. (2023). Sovereign securities (x-axis) vs stock of loans (y-axis), both as a share of total assets. Each observation denotes one bank in a given month. The panels show the seemingly negative relationship between banks’ government bonds holdings-to-assets ratio and loans-to-asset ratio (i.e. loans to corporates). The circle sizes are weighted according to bank size (value of bank’s assets).

An empirical investigation

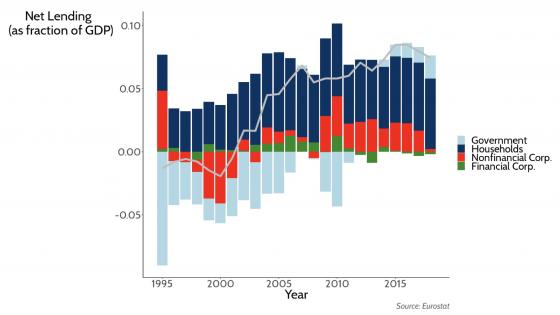

To empirically test the crowding-out hypothesis, we centre on a particular case study: Colombia, a small open economy. In Figure 2, we plot, on the horizontal axis, the banking sector’s take-up of government bonds and, on the vertical axis, the banking sector’s corporate loan portfolio (both as a share of total assets, where circle sizes are weighted according to bank size). The seemingly negative relationship is confirmed with an innovative identification strategy: we compare the lending behaviour of banks that barely met the criteria of being a primary dealer with those that barely missed the cut-off. To give some context, primary dealers are required by regulation to take on an established amount of government debt, and hence, a part of bond purchases in this market are not readily adjusted in banks’ portfolio decisions and are more likely to be passed on as liquidity shortages to firms, dampening their credit lines. In another exercise, we then compare primary dealers by investigating barely winners and losers at each auction.

This and other accompanying exercises yield similar results. In particular, we find that a one percentage point increase in primary dealer banks’ bonds-to-assets ratio decreases loans by 0.2%. We also find that the affected firms are only partially able to substitute their loans with other lenders. Additionally, we find heterogeneous lending effects across firms: we show that the crowding-out effect is differentially lower for older and larger firms, for firms with more workers, and for firms with higher profits. Hence, these firms can cope better when faced with a sudden decrease in their credit lines. Finally, we evaluate the effects on firm’s outcomes and find that credit exposure (i.e. a government debt increase of one percentage point of GDP) leads to a decline in liabilities, investment, profits, wages, and employment of 0.22%, 1.4%, 0.29%, 0.81%, and 0.16%, respectively.

These results are in line with some of the related literature, such as Holmstrom and Tirole (1997), who show that capital tightening mostly affects poorly capitalised firms. Also, Chodorow-Reich (2014) shows that lender health affects employment at small and medium firms. Perez (2015) shows that an abundant supply of public debt makes banks shift towards government securities and substitute away from investments in their less productive projects. Overall, this analysis is relevant because if banks are cutting more on low-productivity firms, this will reduce the misallocation in the economy. On the other hand, it warrants public policies targeted at the most vulnerable firms.

A quantitative model of crowding-out

In our paper, we also postulate a crowding-out model of public debt to provide a theoretical framework – useful for interpreting our empirical findings. Nonetheless, to bridge the gap between our empirical results and the quantitative section, we conduct some simplifications. For instance, we focus solely on primary dealer banks in a closed economy context. As a result, the lending capacity of the banking sector is fixed. In other words, an increase in government spending leads to a reduction in available credit for firms, as borrowing from abroad is not considered by agents in the economy.

Our main objective is to examine the response to an unexpected borrowing shock by the government. Specifically, we aim to understand how the economy reacts when the government’s funding pressures are transferred to primary dealer banks as it borrows in an unforeseen manner.

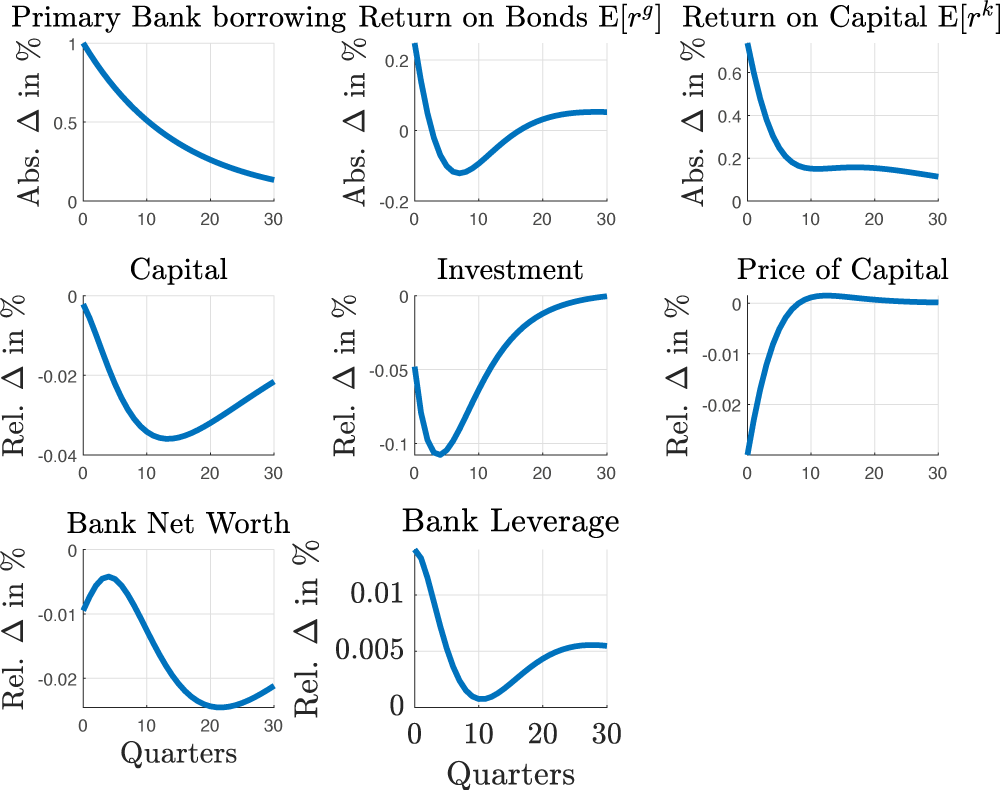

When the government increases its borrowing unexpectedly (depicted in the first panel of Figure 3), it leads to a crowding-out effect on bank loans due to the limitation on expanding banks’ balance sheets. This, in turn, reduces other assets like endogenous public debt holdings and loans to firms. The initial impact of the borrowing increase is evident in the significant rise in expected interest rates and borrowing costs.

As borrowing costs rise, goods producers reduce their capital demand, resulting in a crowding-out effect on investment by capital producers. Interestingly, the decline in investment is amplified despite the shock being mean-reverting. This is due to the financial accelerator mechanism, which is driven by the cyclical variation in the bank’s balance sheet. A decrease in investment lowers the capital price, leading to a devaluation of claims on intermediate goods firms and further tightening of the bank’s net worth. This, in turn, imposes stricter leverage constraints on banks when providing loans to producers and the government.

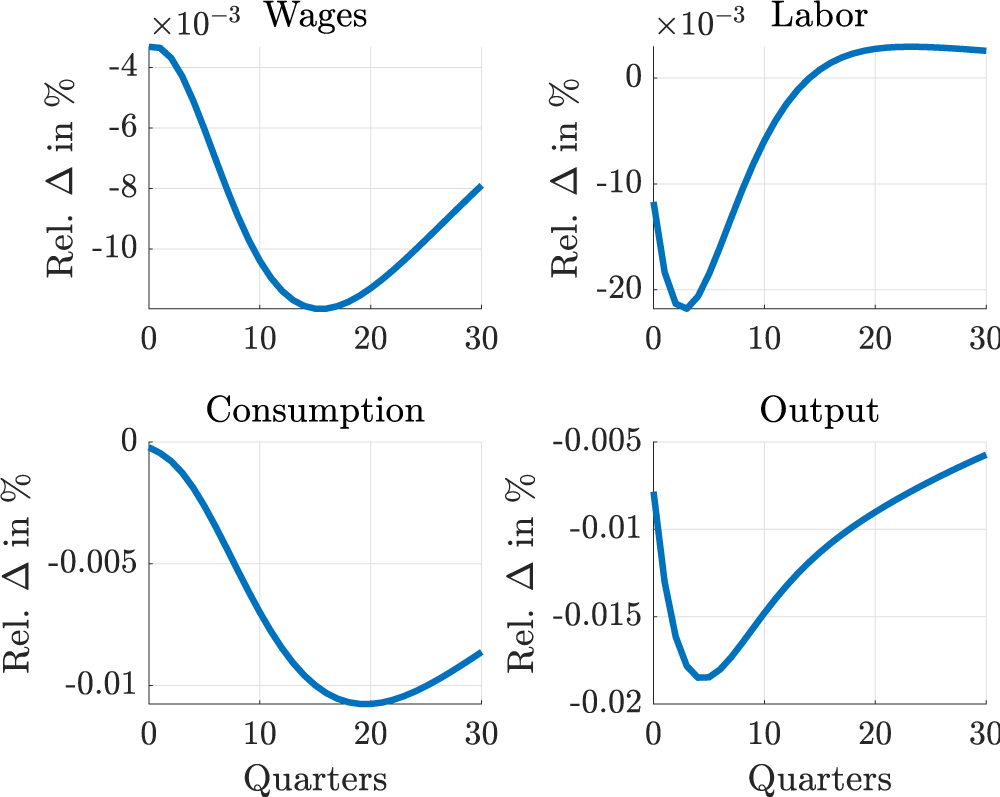

This chain of events triggers higher borrowing costs, continued crowding-out of investment, lower asset prices, contraction of the bank’s net worth, and so forth. As a result, a severe credit crunch occurs in the economy. Figure 4 illustrates how this chain reaction affects the entire economy, manifested in reduced wages for workers and a discouraged labour supply. This, in turn, tightens household budget constraints, leading to a decline in consumption.

Figure 3 Impulse-response functions

Figure 4 Impulse-response functions

Note: The figures are from Önder et al. (2023).

Conclusion

Our findings shed light on how increased government borrowing impacts the dynamics of economic activity and hampers private investment. Specifically, we observe that a higher bonds-to-assets ratio for banks lowers the number of loans provided to firms. We demonstrate that the crowding-out effect is relatively less pronounced for older and larger firms, firms with a larger workforce, and firms with higher profitability. This suggests that these types of firms are more resilient when faced with a sudden reduction in their credit lines. Our empirical and quantitative findings provide insights into the interplay between government borrowing, financial sectors, and firm outcomes. They highlight the potential consequences of increased government spending on private investment and overall economic performance.

References

Alesina, A and S Ardagna (2010), “Large Changes in Fiscal Policy: Taxes versus Spending”, Tax Policy and the Economy, Vol 24/1.

Brancati, E, F Schiantarelli and P Balduzzi (2018), “Crowding out risk: Sovereign debt, banks, and firms’ investment in Italy”, VoxEU.org, 9 November.

Chodorow-Reich, G (2014), “The employment effects of credit market disruptions: Firm-level evidence from the 2008-9 financial crisis”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 129(1): 1–59.

Gertler, M and P Karadi (2011), “A model of unconventional monetary policy”, Journal of Monetary Economics 58(1): 17-34.

Holmstrom, B and J Tirole (1997), “Financial intermediation, loanable funds, and the real sector”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 112(3): 663–691.

Önder, Y K, S Restrepo-Tamayo, M A Ruiz-Sanchez and M Villamizar-Villegas (2023), “Government Borrowing and Crowding Out”, American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, forthcoming.

Ramey, V (2018), “Ten years after the Financial Crisis: What have we learned from the renaissance of fiscal research?”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, forthcoming.

Woodford, M (1990), “Public Debt as Private Liquidity”, American Economic Review 80(2): 382–388.