A growing number of studies indicate that simply providing children with access to home computers and internet does not improve academic achievement. Some, based on randomised control trials in Peru and the US find null effects (Fairlie and Robinson 2013, Beuermann et al. 2014, Malamud et al. 2018). Others, based on quasi-experimental methods in Romania and the US, even find negative effects (Malamud and Pop-Eleches 2011, Vigdor et al. 2014). Given that computers represent such a versatile technology, the potential risks and benefits of computer use are likely to depend on parental involvement. Indeed, Malamud and Pop-Eleches (2011) found that parental rules for homework and computer use attenuated the negative effects of computer ownership, suggesting that parental monitoring and supervision may be an important mediating factor.

In a recent study, we examine two factors that may affect parents’ ability to monitor their children’s internet use (Gallego et al. 2017). First, parents may lack information about their children’s internet use.[1] Children are often quicker to adapt to new technologies and parents therefore encounter challenges in understanding how children use technology. Second, even with perfect information, parents may not be able to influence their children’s actions through indirect transfers and threats (Weinberg 2001, Berry 2015). In these cases, parents may wish for the possibility of controlling their children’s actions directly. We designed and implemented a set of randomised interventions to test the impact of sending parents weekly SMS messages containing specific information about their children’s recent internet use and/or encouragement and assistance with installing parental control software. Providing parents with information about their children’s internet use should help alleviate informational frictions. Encouraging parents to install parental control software can help parents bypass the need to incentivise their children or enforce rules related to computer use, assuming that parents are able to install and operate such parental control software.

As part of this study, we also sought to understand how and why the provision of information affects behaviour. To this end, we designed our interventions to separate the informational content from the cue associated with the SMS messages, and attempted to vary the strength or salience of the cues by randomly assigning whether parents received messages in a predictable or unpredictable fashion. This was inspired by research in neuroscience that suggests that human responses may be related to the predictability or novelty of the stimuli (Parkin 1997, Berns et al. 2001, Fenker et al. 2008). It is also closely related to research in psychology on how different schedules of reinforcement affect behaviour (Ferster and Skinner 1957).

Context and experimental design

We focus on a sample of children in 7th and 8th grade who received free computers and 12 months of free internet subscriptions through Chile’s “Yo Elijo mi PC” (YEMPC) programme in 2013. We have data on the intensity of internet use at the daily level from the internet service provider (ISP) which served all of the computers provided to the children in our sample. According to these data, children downloaded approximately 150MB of internet content daily, which translates to about three hours of internet use on a daily basis. This is similar to recent estimates from a 2015 PISA survey showing that children in Chile spent 195-230 minutes per day online, the highest rate among all the OECD countries surveyed (OECD 2017). To put this in context, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends no more than two hours of screen time for children (AAP 2016).

The experiment consisted of delivering weekly text messages to the 7,700 parents in our experimental sample over the course of 14 weeks. The SMSs differed in terms of content and the day of the week in which they were delivered. In terms of contents, we sent three types of SMSs using the following texts:

- SMS-only: “We hope your child makes good use of the Yo Elijo Mi PC laptop that he/she won”.

- ISP: “We hope your child makes good use of the Yo Elijo Mi PC laptop that he/she won. Your child downloaded XX MBs the week of the DD-MMM, {“more than", or “similar to", or “less than"} what a typical child downloaded: YY MBs.”[2]

- W8: “We hope your child makes good use of the Yo Elijo Mi PC laptop that he/she won. The Parental Control program of Windows 8 can help you supervise your child's computer use. Call us at XXX-XXXX for assistance.”

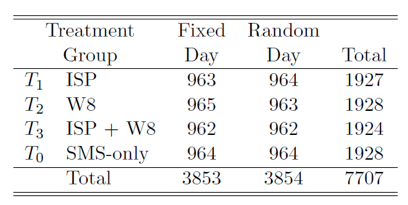

For each group, half of the parents received the treatments on a fixed day of the week (and we randomised the day on which they received the message) and half of the parents received the messages on random days of each week. We also incorporated a treatment arm that included both ISP information and assistance with W8 parental controls to test for possible interactions between these treatments. Table 1 shows how the sample was divided across the different treatments conditions:.

Table 1

To disentangle the informational content and the offer of assistance from the cue associated with SMS messages, we compare the ISP and W8 treatments to the SMS-only control group in which parents received a weekly SMS reminding them that children should make good use of their computers, a message that was included in every treatment.

Main findings

We have three main sets of results.

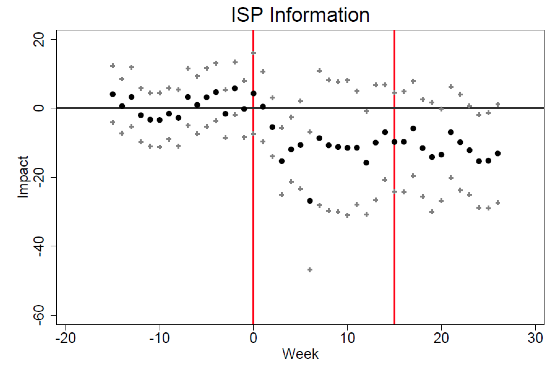

- First, we find that households in which parents received ISP information about internet use had a 6-10% lower intensity of internet use during the treatment period relative to households in the control group.

These effects persist in the weeks and months after treatment ended. They do not reflect declines in parents’ own internet use. This suggests that our temporary intervention providing information on internet use may have altered the permanent intra-household equilibrium. This can be seen in Figure 1, which shows the estimated impacts (and confidence intervals) of the ISP information treatment on weekly Internet use relative to the control group (where the red vertical lines bracket the intervention period).

Figure 1

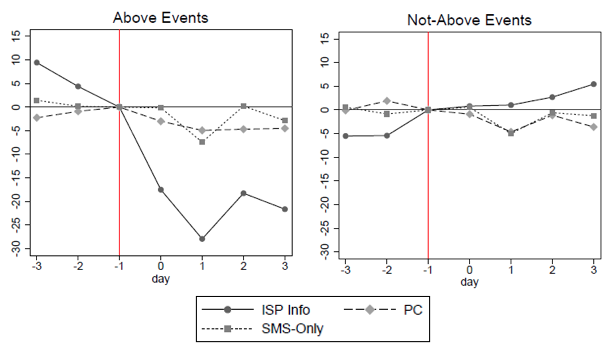

We also show that there are statistically significant reductions in use precisely on the days immediately after receiving the ISP information and this effect is more relevant in the early weeks of the experiment. Moreover, it is the SMS messages that convey the ‘bad news’, i.e. that children used more internet than the reference group in a specific week, which produce a much larger decline in internet use. Thus, Figure 2 presents the estimated impact for each treatment group around the reception of an SMS message (where day 0 marks the day on which the SMS messages are received each week). The ‘above’ events correspond to the weeks when parents received an SMS message that children had above-average internet use relative to the reference group.

Figure 2

These findings confirm that it is the specific information provided to parents about their children’s internet use that leads to a significant reduction of internet use.

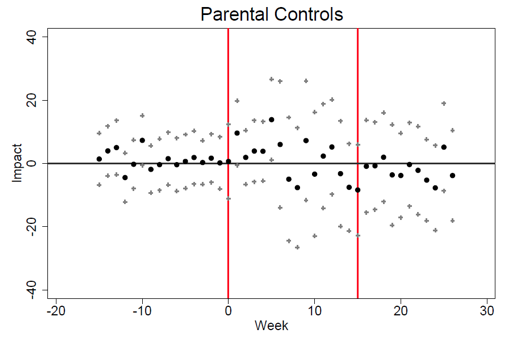

- Second, we do not find significant impacts from helping parents directly control their children’s internet access.

In particular, we do not find a difference in internet use between parents who were encouraged and provided assistance to install parental control software as compared with those in the control group who only received a generic cue. This can be seen in Figure 3 which shows the estimated effects (and confidence intervals) of the parental control treatment on weekly internet use relative to the control group (where the red vertical lines bracket the intervention period).

Figure 3

Take-up of this intervention was only 15% when measured in terms of the parents who actually responded to our messages. However, for those taking up the intervention, we do not find changes in internet use even on the days immediately after installing the parental control settings.

- Finally, we have several results that help us open the ‘black box’ of how messages that contain information affect behaviour.

As mentioned above, by sending messages that vary the amount of information, we can show the important role of a message’s informational content on reducing internet use. Our analysis also shows two additional findings that suggest the importance of salience. When we experimentally varied the strength of the cue, we find that households who received SMS messages on a random schedule experienced significantly greater reductions in internet use than those on fixed schedules, an effect similar in magnitude to the main effect associated with receiving the ISP information. Furthermore, we find that even the SMS messages sent to the control group had short-term impacts on internet use in the first weeks of the experiment, perhaps due to the novelty of the message.

Discussion

Taken together, these findings indicate that providing parents with specific information about their children’s internet use affects behaviour, while providing parents with parental control software does not. The fact that the impacts of information effects persist after treatment ends suggests that our temporary intervention may have altered the equilibrium level of internet use and alleviated the problem of imperfect information in a more permanent way, perhaps by altering the habits and routines of how parents engage with their children. The fact that there is no impact of parental control software may reflect the considerable obstacles faced by low-income parents in implementing technological solutions for monitoring and supervising their children.

We also find strong evidence that households who received SMS messages with an unpredictable schedule experienced significantly greater reductions in internet use than those on predictable schedules, an effect similar in magnitude to the main effect associated with receiving the ISP information. In addition, we find that the SMS messages sent to the control group had short-term impacts on internet use in the first weeks of the experiment, perhaps due to the novelty of the message. These findings suggest that the cues associated with messages have an independent effect on behaviour and that the strength of such cues is an important determinant of our outcomes. This is relevant for designing future interventions that incorporate messages for affecting behaviour.

References

American Academy of Pediatrics (2016), “Policy Statement: Media Use in School-Aged Children and Adolescents”, Pediatrics 138(5).

Berry, J (2015), “Child Control in Education Decisions: An Evaluation of Targeted Incentives to Learn in India”, Journal of Human Resources 50(4): 1051-1080

Berns, G et al. (2001), “Predictability Modulates Human Brain Response to Reward”, The Journal of Neuroscience 21(8):2793–2798

Beuermann, D, J Cristia, S Cueto, O Malamud, and Y Cruz-Aguayo (2015), “One Laptop per Child at Home: Short-Term Impacts from a Randomized Experiment in Peru”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 7(2): 1-29.

Bursztyn, L and L Coffman (2012).,“The Schooling Decision: Family Preferences, Intergenerational Conflict, and Moral Hazard in the Brazilian Favelas”, Journal of Political Economy 120(3): 359-397.

Fairlie, R, and J Robinson (2013), “Experimental Evidence on the Effects of Home Computers on Academic Achievement among Schoolchildren”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 5(3): 211–240.

Fenker, D B, J U Frey, H Schuetze, D Heipertz, H-J Heinze, and E Duzel (2008), “Novel Scenes Improve Recollection and Recall of Words”, Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience 20(7):1250–1265

Ferster, C B and B F Skinner (1957), Schedules of Reinforcement. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Gallego, F, O Malamud and C Pop-Eleches (2017), “Parental Monitoring and Children's Internet Use: The Role of Information, Control, and Cues”, NBER Working Paper No. 23982.

Malamud, O and C Pop-Eleches (2011), “Home Computer Use and the Development of Human Capital”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 126: 987–1027.

OECD (2017), PISA 2015 Results (Volume III): Students’ Well-Being, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Parkin, A J (1997), “Human memory: Novelty, association and the brain”, Current Biology 7: 768–769

Vigdor, J, H Ladd and E Martinez (2014), “Scaling the Digital Divide: Home Computer Technology and Student Achievement”, Economic Inquiry 52(3): 1103-1119.

Weinberg, B (2001), “An Incentive Model of the Effect of Parental Income on Children”, Journal of Political Economy 109(2): 266-280

Endnotes

[1] For example, Bursztyn and Coffman (2012) provide evidence for asymmetric information between parents and children in Brazil.

[2] A randomly selected “reference group” was used to compute the weekly average of MBs downloaded by the typical child.