A crucial discipline for understanding how our past was shaped by economic trends and forces, economic history also informs our thinking about present and future economic realities (Abramitzky 2015, Diebolt and Haupert 2018, Eichengreen 2018, Margo 2018). Because it has enormous potential to contribute to debates in economics and public policy, it is a matter of great interest to elucidate how this area of academic inquiry has evolved, in terms of its central debates and publishing trends.

Using details from articles published since 1980 in the eight main journals in economic history (Table 1), in this column I review the development of the discipline with a network analysis that maps out disciplinary silos in authorship and areas of inquiry (Galofré-Vilà 2020). Although journals in economics, demography, and sociology also publish the findings of economic historians,1 I focus on papers published by the top economic history journals, namely, those publishing articles that capture the main debates and interests in the research area under scrutiny here.

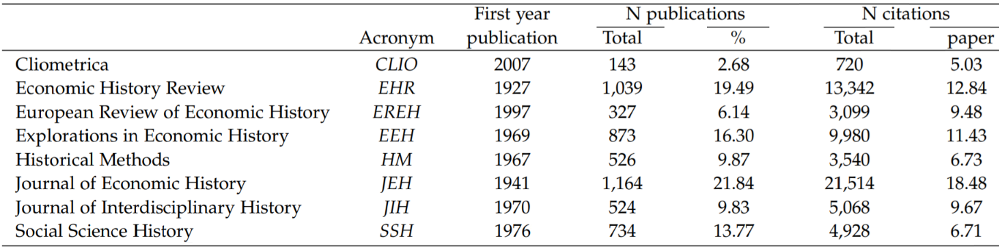

Table 1 Journals included in the review

Network analysis in economic history

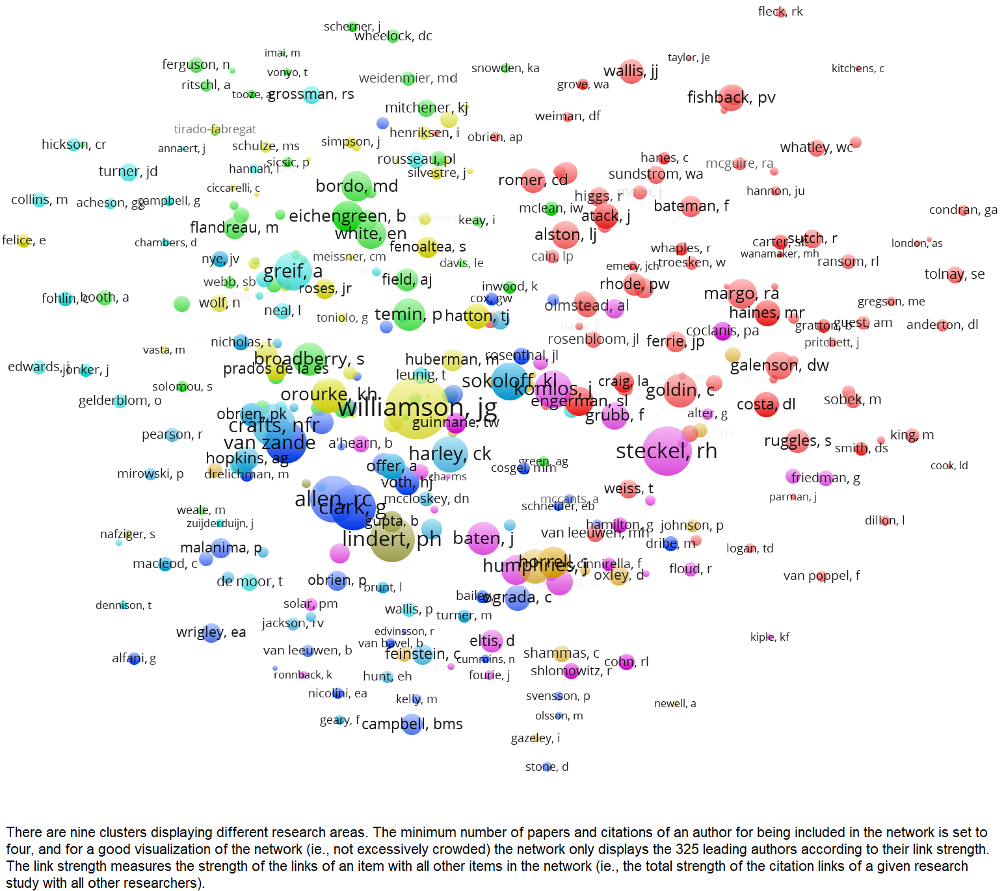

Figure 1 shows the relatedness among research fields in economic history. Network analysis is based on the assumption that authors cited together share some intellectual affinity; a network map captures how authors (and, consequently, the ideas and debates associated with them) sit in relation to each other across the field. In the network map, bubble sizes (nodes) correspond to the number of citations received by each author, while the distance between bubbles corresponds to the tendency for authors to be cited together within articles. Clusters (represented by different colours) group together bubbles (authors) that display some degree of similarity in research topics or debates.

Judging by bubble size and position, the most important economic historian in the network is Jeffrey Williamson, who is known for showing that globalisation began in the early 19th century and not before (during the time of Columbus) and for exploring income distribution in the US since 1650. He is followed by Robert Allen, whose ‘high wage economy’ thesis alleged that England industrialised first; Nicholas Crafts, who conducted research on ‘growth accounting’ and England’s industrialisation; Richard Steckel, who shed new light on the health of slaves in the US and the development of well-being in the US and Europe over the very long-run; and Peter Lindert, who explored the causes and effects of modern fiscal redistribution and the interaction between social spending and economic growth. From a list including 325 scholars, other well-positioned economic historians in the network are Gregory Clark, Jan Luiten van Zanden, Sara Horrell, Stephen Broadberry, Joerg Baten, Jane Humphries, Knick Harley, John Komlos, Robert Margo, Cormac Ó Gráda, David Jacks, John Turner, Kevin O’Rourke, Deborah Oxley, Price Fishback and Hans-Joachim Voth.

Figure 1 Authors’ publications

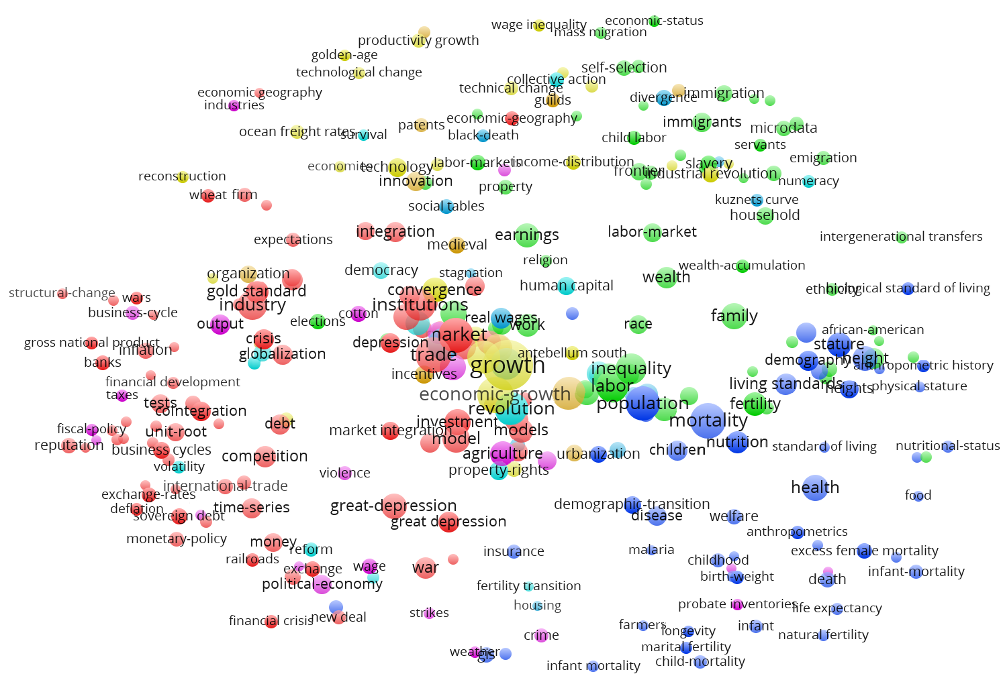

Network analysis also allows us to visualise what economic historians are studying and the main debates within the discipline. Figure 2 maps the keywords listed in the articles studied. Yellow bubbles capture research on economic growth; exploring why some countries became rich while others stayed poor has been the most important area in terms of publications. Another vigorous area of research has been the social history of demography, and the blue bubbles represent work exploring changes in fertility, health and mortality. Green bubbles correspond to papers devoted to changes in inequality driven by wealth, labour markets, and migration. Bubbles in turquoise (tracking keywords such as ‘revolution’, ‘real wages’, and ‘property rights’) connect with yellow and blue bubbles at the crowded centre of the network, and with some thematic areas (red bubbles) such as market, economic depressions, the gold standard, and railroads. Red bubbles also include some statistical keywords, such as ‘models’, ‘time-series’, and ‘cointegration’, which display the important component of statistics in the discipline.

Figure 2 Thematic areas

Recent trends in publications

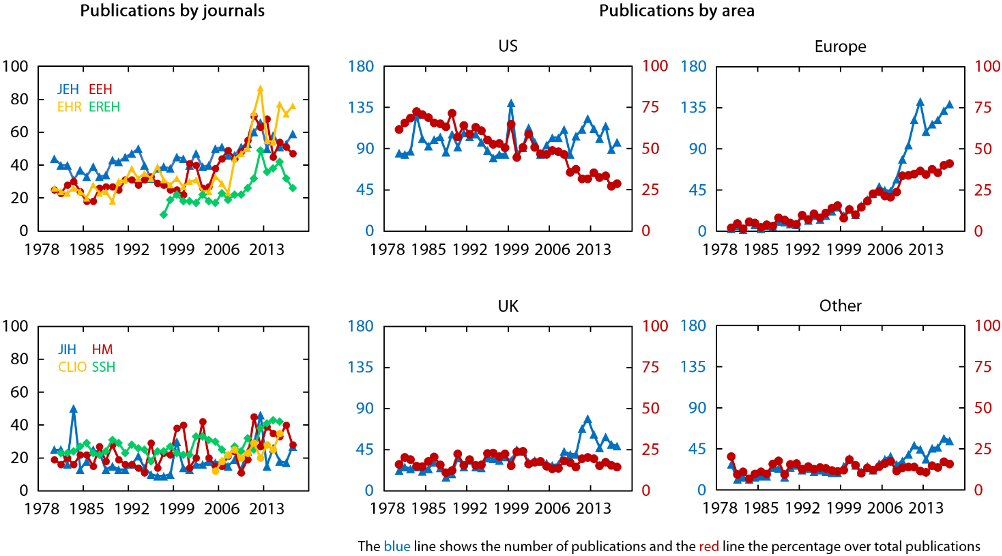

Figure 3 shows that the number of publications in the main economic history journals remained fairly constant between 1980 and 2000, and then rapidly accelerated after 2000 – a rise driven by a shift in publication distribution from the US/UK to continental Europe. The percentage of articles published in the top economic history journals by scholars working in US universities plummeted between 1980 and 2020, from 60% to 30% of all scholars, whereas economic historians working in UK and non-European universities (chiefly Canada, Australia, and Japan) maintained their publication shares at 17% and 14%, respectively. Hence, the rise in the number of publications since the early 2000s appears to be due to continental European-based economic historians; countries most responsible for the change in the publication trend were Germany, the Netherlands, Spain, and Italy.

European universities are not only leading the discipline in terms of quantity (number of publications), but also in terms of quality (as measured by the adjusted number of citations). For instance, since 2010, these universities received an average of 5.5 citations per published paper, compared to 5.3 in the UK, 4.2 in the US, and 3.8 outside these three areas. This hierarchy differs in earlier periods. From 1980-1989, the US was the leader in accumulating citations (18.8 citations per paper), followed by the UK (15.0), Europe (13.0), and other areas (12.7). From 1990-1999, the UK led (with 17.6 citations per paper), followed by the US (15.7), Europe (14.6), and outside these three areas (11.6).

Figure 3 Journal publications and publications by main continental areas

Economic history is a dynamic discipline, and the evolution of publication trends provides clear evidence that a healthy variety of topics captures the attention of researchers across the globe. We cannot know how the field will evolve, but as we enter the third decade of the 21st century, economic historians looking backward have every reason to look forward with confidence and excitement at an increasingly open-ended and diverse future.

References

Abramitzky, R (2015), “Economics and the Modern Economic Historian”, Journal of Economic History 75: 1240-1251.

Acemoglu, D, S Johnson and J A Robinson (2002), “Reversal of Fortune: Geography and Institutions in the Making of the Modern World Income Distribution”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 117(4): 1231–1294.

Diebolt, C and M Haupert (2018), “We Are Ninjas: How Economic History has Infiltrated Economics”, Unpublished manuscript.

Eichengreen, B (2018), The Populist Temptation: Economic Grievance and Political Reaction in the Modern Era, Oxford University Press.

Galofré-Vilà, G (2020), “The Past’s Long Shadow. A Systematic Review and Network Analysis of Economic History”, Research in Economic History (Forthcoming in vol. 36).

Margo, R A (2018), “The Integration of Economic History into Economics”, Cliometrica 12:3, 377-406.

Endnotes

1 For instance, economic history papers published in the top five economic journals are narrowly focused on persistence studies that explain present outcomes as a function of events in the distant past. Acemoglu et al. (2002) is a good example of this practice.

2 While the rise of publications by scholars in European universities correlates with the launch of two European journals (EREH and CLIO), the appearance of these two journals does not seem to explain the success of European scholars. Nearly half of the articles published by these two journals were signed by non-European scholars, and since 2000, European-based scholars also increased their share in Anglo-Saxon journals.

3 The EU14 group consists of Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, and Sweden.

4 Naturally, older papers are more likely to accumulate citations.