In recent years, competition authorities have been particularly concerned by the behaviour of dominant firms in two-sided markets, which provide services on one side and generate revenues on the other in a way that could harm the interests of consumers.1

The market of online service providers

The online service providers include search engines such as Google, Bing, and Yahoo, social networks such as Facebook and Twitter, online trading platforms like eBay and Amazon, as well as the numerous official websites of different brands. Besides the brands’ official websites (which aim to promote and sell products of behalf of their brands, and do not include advertising), the business models of all the other online service providers are two-sided. On the one side, the platforms provide services to the visitors free of charge. On the other side, the platforms sell sponsored spaces to the advertisers.

Network effects matter for the earnings of these two-sided platforms. The advertisers target visitors of platforms on which they advertise. In general terms, the larger the number of visitors a platform receives, the more attractive to advertisers it is. The attitude of visitors toward sponsored advertising can be different according to the types of service providers. For example, visitors of search engines may be indifferent since these platforms display only advertisements related to the ‘enquiries’ of visitors and the unsponsored advertisements are displayed at the same time with the sponsored ones (although under different ranking). Advertising on the social networks is probably viewed as a nuisance by their visitors since these advertisements are not ‘enquired’. However, the visitors of the online trading platforms may welcome the display of advertisements since they provide useful information. In case where the visitors dislike advertising, the platforms face a trade-off between not including too much advertisements (to avoid losing visitors) and having enough advertisements to ensure the platforms’ revenues.

Competition exists (at least to some extent) between the different online service providers. The same advertisements are often displayed simultaneously on many different platforms and the advertisers pay the online service providers on a ‘per-click’ basic. While internet users are spending a significant amount of time online, the variance of their attention is considered as large. One finds the ‘searched product’ either by navigation on an advertising-financed online service provider (such as those listed above) or by logging directly into the brands’ websites. What remains to be assessed is how much market power is enjoyed by the so-called ‘dominant’ platforms? What is the degree of competition on the online advertising market?

Unfortunately, while it is crucial for competition policy to learn more on how these markets are functioning, little empirical research has been done along these lines. Indeed, dominant firms often provide better services than their rivals without charging an extra monetary price to their users. In this way, the dominant firms attract more users which, in turn, increases their attractiveness in the advertising market. While consumers enjoy a free service from these firms, they may be overwhelmed by the amount of advertising. This can be even more problematic when the dominant media companies get bigger by acquiring smaller competitors. On the one hand, the dominant firms can offer better services by expanding their customer base, which allows them to show more advertisements (as a non-monetary price) to their users. On the other hand, the acquisition can increase the market power of the merging firms in the advertising market, which allows them to charge higher prices to the advertisers.

To get more insights on the competition landscape in this type of markets, we examine the digital TV industry in which data are available to perform an econometric investigation.

A merger decision in the digital TV market

In January 2010, the ‘Autorité de la concurrence’ (the French competition authority) cleared the acquisition of two free broadcast TV channels – NT1 and TMC – by the TF1 Group, subject to a behavioural remedy requiring that channels NT1 and TMC sell their advertising time separately from the main channel of TF1 Group (channel TF1). In practice, the decision prohibits the merger between the advertising sales house of channel TF1 and those of NT1 and TMC. As a result, only the broadcasting content of the three channels is allowed to be managed jointly following the acquisition.2 The competition authority had concluded that the acquisition would have a positive impact on the broadcasting side, since NT1 and TMC could benefit from the large catalogue of programmes of the TF1 Group (due to its partnership with numerous other content providers). Having more channels offering high-quality content could enhance the competition between the different TV broadcasters for audience. The authority was, however, concerned about the potential anti-competitive effects of merging the advertising sales houses of the three channels, due to the dominant position of the TF1 Group in the TV advertising market. Before the acquisition, the sales house of TF1 held a 40% market share, while the sales houses of NT1 and TMC held a 5% market share. The merger could simply reinforce the position of the TF1 Group in the advertising market, which would translate into an increase in either the amount of advertising or its price. To avoid any detrimental effect of the acquisition on the TV advertising market, the authority decided to impose this behavioural remedy for a period of at least five years.

While the competition authority’s examinations of both the broadcasting and advertising sides of the market were straightforward, its decision nevertheless treated the channels’ advertising services separately from their broadcasting services. In Ivaldi and Zhang (2020), we show that ignoring the interaction between the two sides of the market can result in unexpected outcomes. We now summarise the main ingredients of our analysis and draw some policy recommendations.

TV stations as two-sided platforms

TV stations can indeed be considered as two-sided market platforms connecting viewers to advertisers.3 They provide two services: TV shows to viewers on one side, and advertising slots to advertisers on the other. While viewers enjoy the news and entertainment content on TV, they receive the flow of advertising. When TV viewers see the advertisements, this generates an audience for the advertisers. TV viewers may, however, be sensitive to the amount of advertising, in which case the advertisers generate externalities for the TV viewers. Advertisers ‘value’ TV advertising for its ability to inform and/or persuade viewers of the merits of products or services they have to commercialise. Therefore, a priori, the more popular a TV channel is among viewers, the more demanded it is by advertisers.

Our reduced-form analysis exhibits a negative correlation between the amount of advertising and the viewership, demonstrating that advertisers' willingness to pay is higher for the ‘advertising seconds’ of a channel which attracts more viewers. These results support the view of TV stations as two-sided platforms. Our structural analysis provides evidence on the sign and the magnitude of the externalities between the two sides of TV stations.

Merger evaluation

Based on the two-sided nature of TV stations, and by using a comprehensive dataset on the French digital TV market which covers two years of the pre-acquisition period and three years of the post-acquisition period, we build a structural model to evaluate the consequences of the merger described above, and the effectiveness of the competition authority’s decision.

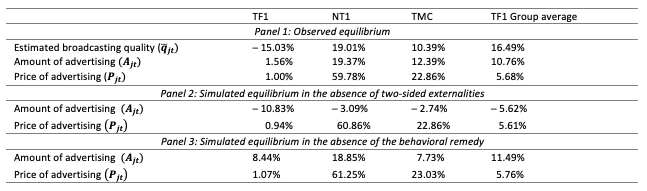

Using post-acquisition data, we observe that the broadcasting quality of the two purchased channels has increased, but the advertising sales houses reacted to the changes in the broadcasting quality of TV channels by adjusting their amounts (and hence the prices) of advertising (see panel 1 of Table 1).

Counterfactual simulations then show three results that illustrate the complexity of interdependencies in this type of markets. These results are drawn from the comparison of the simulated acquisition effects (displayed in panel 2 of Table 1) to the observed acquisition effects displayed in panel 1.

First, if there were no negative externalities that advertisers generate for viewers, the advertising sales houses would respond to the increase in willingness of advertisers to pay for the advertising slots of the merging channels (as a result of the increase in their broadcasting quality and therefore their viewership) by restricting their total amounts of advertising slots, thereby increasing their prices. Second, the two-sided network externalities between viewers and advertisers further incentivise the advertising sales houses to increase the amount of advertising on the merging channels following the increase in their broadcasting quality (since viewers are less sensitive to the amount of advertising during programmes of better quality). Finally, the joint effect of the changes in broadcasting quality and the two-sided network externalities results in an increase in both the amounts and prices of advertising of the merging channels.

Table 1 Comparing observed and simulated post-merger equilibria

Note: The percentage changes are taken over the post-acquisition years from 2010 to 2013

To assess the effectiveness of the implemented behavioural remedy imposed by the competition authority, we can compare the observed market equilibrium with a counterfactual situation in which one unique advertising sales house determines the amounts of advertising of the three channels in order to maximise their joint profits. As we observe the quality adjustment of different TV channels following the acquisition, the counterfactual simulation takes into account the effect of the acquisition on product quality.

Comparing the numbers presented in panel 3 of Table 1 to the numbers presented in Panel 1 allows us to reach conclusions about the impacts of the behavioural remedy. It should be noted that merging the advertising sales houses of the three channels has almost no impact on their advertising prices, while their total amount of advertising increases only slightly. More precisely, merging the sales houses of the three channels increases their total amounts of advertising by 6.78%, and increases their average prices by 1.41%. This result is not surprising, provided that the substitution effects of the amount of advertising on the viewers' side are small, and that the advertisers consider the advertising slots of NT1 and of TMC to be complementary to those of TF1. It is well known that a merger between complementary firms should not lead to a significant price increase, since it eliminates a pricing externality (Cournot 1838, Economides and Salop 1992.) The slight increase in amounts of advertising after the merger of the advertising sales houses is due to the internalisation of viewers' substitution between the three channels.

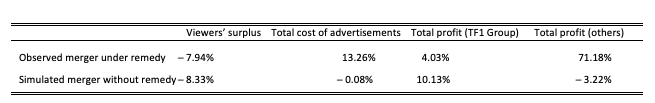

The estimated welfare changes following the acquisition under the behavioural remedy and without the behavioural remedy are presented in Table 2.

Table 2 Welfare analysis of the merger

Note: Results in the first row are computed from the observed equilibrium, results in the second row are computed from the simulated equilibrium presented in Panel 3 of Table 1

The first row of Table 2 presents the welfare effects of the acquisition under the behavioural remedy (i.e. the welfare effects of merging only the broadcasting services of NT1, TMC and TF1). The changes in viewers' surplus in the first row indicate that the surplus of TV viewers has decreased following the acquisition. This is, firstly, because the TF1 Group reallocated some high-quality programmes from TF1 to the two purchased channels, so the broadcasting quality of its major channel (which is also the most popular channel of the market) decreased following the acquisition. In addition, the total amount of advertising increased from 2010 to 2013, which negatively impacted the surplus of TV viewers as well. The presented change in the total cost of advertisements suggests that the advertisers' total costs increased from 2010 to 2013. This is because both the market average amount and price of advertising have increased following the acquisition.

The second row of Table 2 presents the welfare effects of the acquisition without the behavioural remedy (i.e. the welfare effects of merging both the broadcasting services and the advertising sales houses of NT1, TMC, and TF1). Considering the difference between the results in the second row and the results in the first row, we can conclude that the remedy did not have a significant positive effect on the surplus of TV viewers, but significantly increased the total cost for the advertisers. If there were one common advertising sales house which maximised the joint profits from the advertisement slots of the three channels, the other non-merging sales houses would have to reduce their amounts of advertising and prices to attract viewers and advertisers following the acquisition (in reaction to the amount of advertising and prices chosen by the common advertising sales house). The total advertising profits of the advertising sales house of TF1 Group would be higher, while those of the other non-merging sale houses would be lower than in the case in which two separate advertising sales houses manage the advertising slots of NT1, TMC, and TF1 (i.e. the results in the first row of Table 2). Our finding suggests that the implemented behavioural remedy has benefited the advertising sales houses of the TF1 Group's competitors but has disadvantaged advertisers.

Policy discussion

Based on European competition law, the French competition authority should have approved the merger of the advertising sales houses of the three channels, since the consumer surplus remained almost unchanged. However, in the political debate, a decision about whether to approve this merger could be determined according to the weights that the people allocate to the different market players. In any case, the two-sided nature of the market should not be ignored when examining the merger. Hence, the main lesson of our analysis is that in the process of designing competition or regulatory policy for two-sided markets, ignoring the interaction between the two sides of platforms can result in unexpected outcomes.

This conclusion is drawn from the study of the digital TV industry. If more disaggregated data on audience and advertising were available, further investigation to refine this analysis could be undertaken. We expect our analysis could also be helpful for examining similar markets, especially those in which the usage of services on one side is free and all the revenues come from the advertising side.

References

Cournot, A (1838), Recherches sur les principes mathématiques de la théorie de la richesse, Paris: Hachette.

Economides, N and S C Salop (1992), “Competition and integration among complements, and network market structure”, Journal of Industrial Economics 40(1): 105-123

Ivaldi, M and J Zhang (2020), “Platform Mergers: Lessons from a Case in the Digital TV Market”, CEPR Discussion Paper 14895.

Endnotes

1 See for instance the European Commission decision, in March 2019, to fine Google €1.49 billion for abusive practices in online advertising.

2 An ASH handles and sells the advertising time available on the TV stations that it works for.

3 The literature related to our analysis is summarised in Ivaldi and Zhang (2020).