The age of mass emigration from Europe was brought to a shuddering halt in the 1920s. From that time the political economy literature has focused almost exclusively on explaining the ebb and flow of restrictive immigration policies (e.g. Mayda and Facchini 2008, Peri and Mayda 2017, Tabellini 2019, Hatton et al. 2021). In this column, I examine the policies that positively encouraged immigration – specifically to Australia (Hatton 2023a).

Using a panel of six Australian colonies/states from 1862 to 1913, I find that assisted migration policies were positively linked with government budget surpluses and local economic prosperity. They were also influenced by evolving political participation including the widening of the franchise and remuneration of members of parliament. While the reduction in travel time to Australia reduced the need for assisted migration, slumps in the UK increased the take-up of assisted passages.

Assisted passages to Australia

In the 19th century, the Australian colonies competed with the US and Canada as destinations for migrants from the UK. But a passage to Australia cost three times as much and took three times as long as a voyage across the Atlantic (Hatton 2023b). From the mid-19th century, the six quasi-independent Australian colonies (that became states of Australia in 1901) strove to attract migrants from the UK with a variety of assisted passages financed by colonial/state budgets. In the six decades before 1913, almost half of all migrants from the UK to Australia travelled on these assisted passages.

This experience provides a unique opportunity to examine the formation of assisted immigration policies. Existing studies of the evolution of immigration policies focus on sets of countries that differ widely in their cultural, economic, and political systems, as well as in their geographic locations and sources of immigrants (Timmer and Williamson 1998, Peters 2015). In contrast, the six colonies/states studied here (a) share a common culture and institutions, (b) are in the same region, and (c) drew immigrants from a common source – the UK. I focus not only on economic drivers but also on political participation, which, with few exceptions (e.g. Biavaschi and Facchini 2020), existing studies have been unable to do.

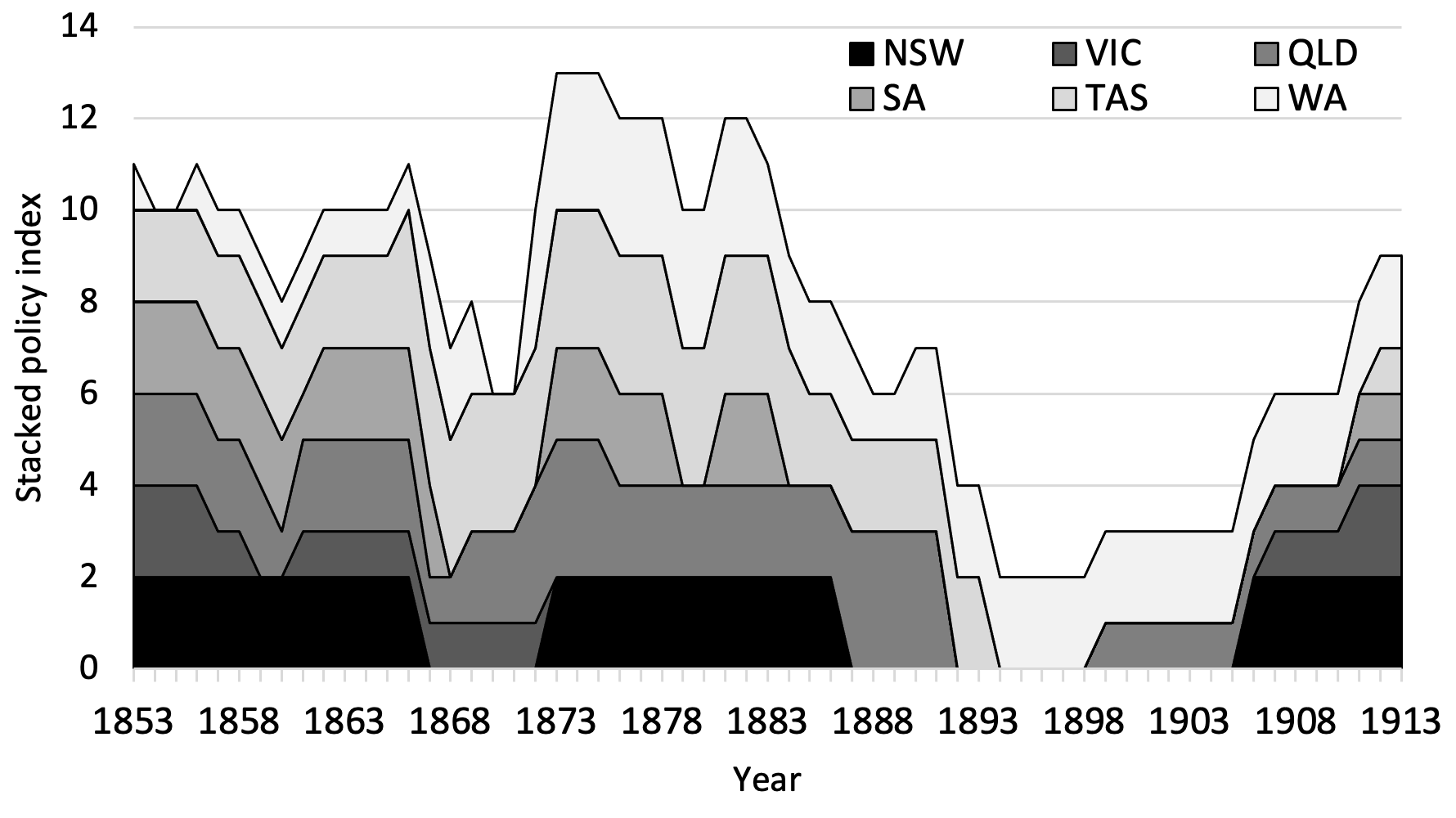

I develop an index of policy effort or intensity based on the three types of policy that provided subsidised passages or financial incentives. These are (1) recruitment and selection of migrants by agents in the UK; (2) nomination of migrants, mainly by friends and relatives in Australia, and (3) grants with which to acquire land. For each colony/state, the index ranges from zero (no policy) to three (all policies in effect). These are displayed as a stacked chart in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Assisted migration policy indices by state/colony (stacked)

Notes: The colonies/states are: New South Wales (NSW), Victoria (VIC), Queensland (QLD), South Australia (SA), Tasmania (TAS), and Western Australia (WA).

Source: Hatton (2023a).

Figure 1 shows diversity in both the intensity and the timing of policies of the individual colonies/states. The overall height of the graph exhibits a temporary dip in the late 1860s and then a gradual retreat from assisted migration from the mid-1880s. This precedes the deep depression of the early 1890s, which is sometimes seen as quashing assisted immigration. Also of note is the revival of assisted immigration from 1906, when the resumption of state-level assistance was promoted by the federal government.

Explaining assisted migration policy

Analysis of this panel of policy indices shows that economic forces mattered. Reflecting the fact that subsidised passages were financed by the colonies/states, the policy index is positively associated with the preceding year’s budget surplus. As would be expected, policy activism is also linked to the demand for labour as reflected by booms and slumps in the local economy.

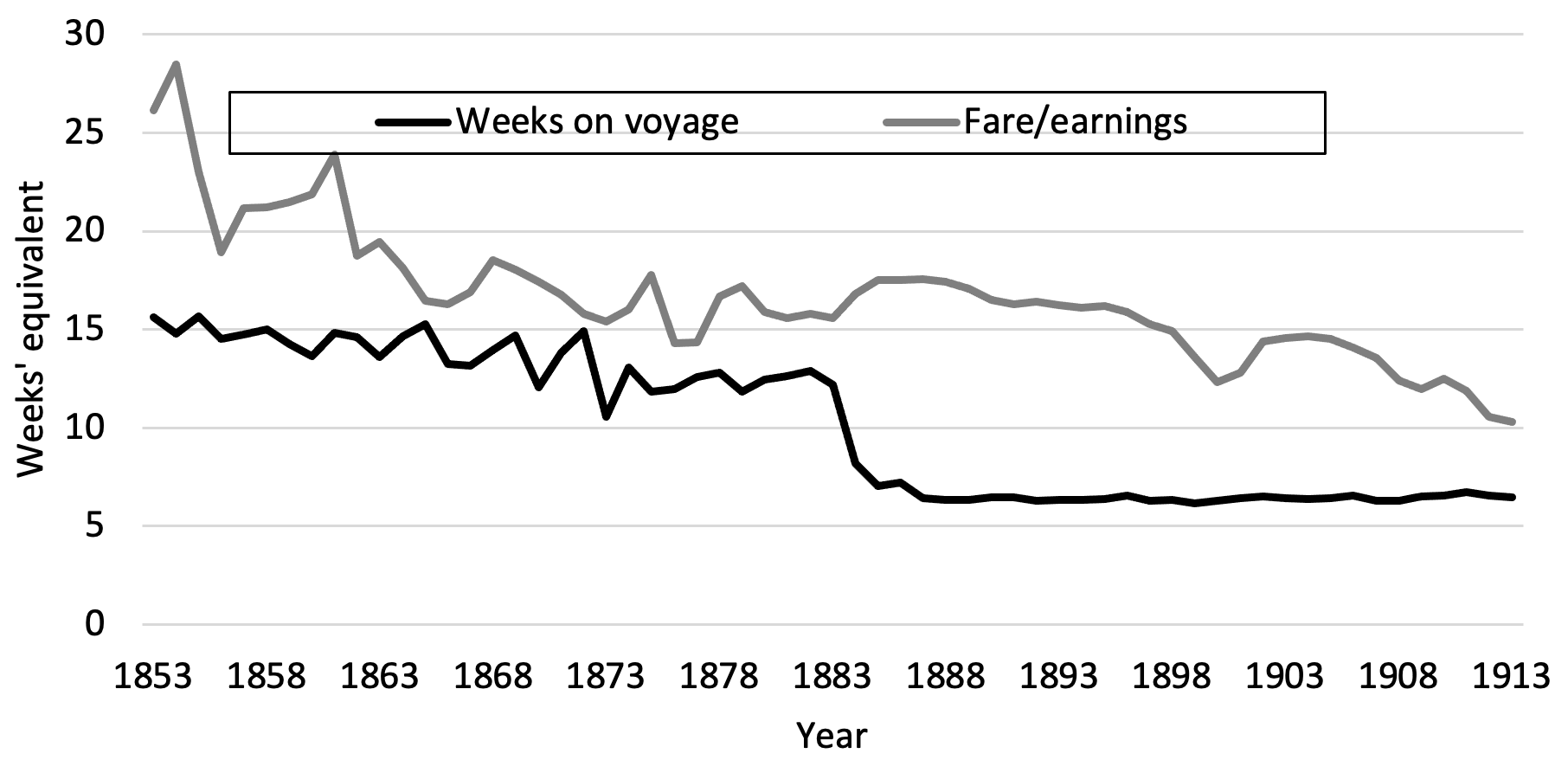

The cost of a passage to Australia (measured in terms of weeks worked at the average UK wage) had offsetting implications for policy: an increase in the cost could make assisted passages more necessary but also less affordable for the colony/state. The policy index, accordingly, is negatively associated with the average duration of emigrant voyages. Figure 2 shows that voyage durations fell sharply in the early 1880s with the transition from sail to steam (see Hatton 2023b). Shorter voyages boosted unassisted migration, which reduced the need for assisted migrants and this helps to explain the overall decline in policy activism from the mid-1880s (Figure 1).

Figure 2 Ticket price in terms of weeks’ work and average voyage duration

Source: Hatton (2023a)

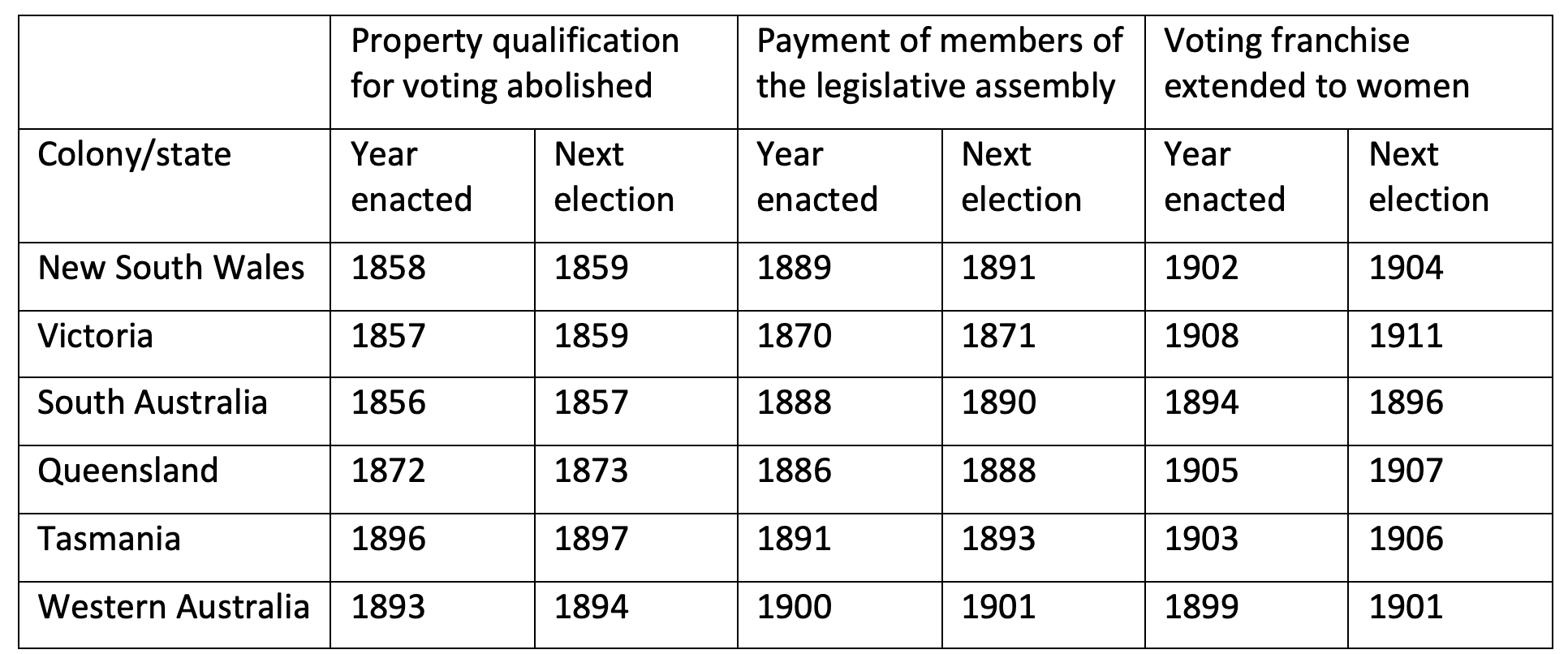

On the political side, the characteristics of the colonial/state premier seem not to matter but participation in the political process does. Table 1 presents the timing of three key electoral/parliamentary reforms. Exploring the relationship of each reform with the policy index shows that the abolition of the property qualification for voting is negatively associated with assisted migration policies. Expanding the (male) franchise amplified the voices of blue-collar interests, which saw assisted migration both as diverting government revenue from other uses and as increasing labour market competition. Payment of members of the legislatures is also linked negatively with policy activism because those voices could now be heard inside the chamber as well as outside.

Table 1 Timing of reforms in the electoral/parliamentary system

Source: Hatton (2023a).

The revival of assisted immigration policies after the 1890s is also linked with political variables. One of these is the enfranchisement of women, which is positively associated with assisted migration policy, even though migration was never a leading issue in the suffrage movement. Even more important was the federal government’s promotion of assisted immigration, which was urged upon the states and involved a high-profile campaign in the UK led by former federal prime minister George Read.

Evaluating the outcomes

The same factors are associated with the number of assisted immigrant arrivals, even though these flows are more volatile than policy. One reason the flows are volatile is that the numbers also depend on the willingness of migrants to take up the assisted packages on offer. In addition to the policy index, or the influences underlying it, the number of migrants is associated negatively with the UK business cycle and positively with the wage gap between Australia and the UK.

Some of the variables associated with assisted migration are those that appear in standard push/pull models of international migration but, in this case, mediated through assisted migration policy. While estimated push/pull models have sometimes been augmented with measures of immigration policy, they have typically not drilled down to the forces underlying those policies. Thus, the Australian experience from 1860 to 1913 provides an interesting laboratory to analyse both the genesis of policy and its implications for the flow of migrants.

References

Biavaschi, C, and G Facchini (2020), “Immigrant franchise and immigration policy: Evidence from the progressive era”, CEPR Discussion Paper 14684.

Hatton, T J (2023a), “The political economy of assisted immigration: Australia 1860–1913”, CEPR Discussion Paper 18275.

Hatton, T J (2023b), “Voyage durations in the age of mass migration”, VoxEU.org, 31 July.

Hatton, T, M Steinhardt, and G Facchini (2021), “Public opinion and immigration policy: The 1965 US Immigration Act”, VoxEU.org, 18 December.

Mayda, A-M, and G Facchini (2008), “From attitudes towards immigration to immigration policy outcomes: Does public opinion rule?”, VoxEU.org, 21 June.

Peri, G, and A-M Mayda (2017), “The economic impact of US immigration policies in the age of Trump”, VoxEU.org, 14 June.

Peters, M E (2015), “Open trade, closed borders: Immigration in the era of globalization”, World Politics 67(1): 114–54.

Tabellini, M (2019), “Gifts of the immigrants, woes of the natives: Lessons from the age of mass migration”, VoxEU.org, 25 May.

Timmer, A S, and J G Williamson (1998), “Immigration policy prior to the 1930s: Labor markets, policy interactions, and globalization backlash”, Population and Development Review 24(4): 739–71.