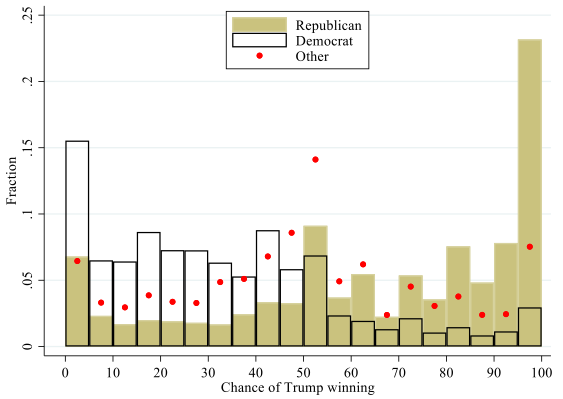

We all have different political preferences. But despite wanting different things, voters should be able to broadly agree on the likelihood of different electoral outcomes, given that much of the relevant polling information is publicly available. This is, in fact, far from being the case. Consistent with recent work showing that Republicans and Democrats disagree about even clear facts (Alesina et al. 2020), we show in a new research paper (Coibion et al. 2020) that the perceived probabilities over different possible outcomes in the 2020 US presidential election differ systematically across party lines. In a large-scale representative survey of US individuals, 87% of Democrats expect Biden to win while 84% of Republicans expect Trump to win. Importantly, this stark disagreement does not reflect two sets of partisan voters each foreseeing a close election that just barely breaks their way. Figure 1 below plots the distribution of respondents’ perceived probabilities of Trump winning re-election broken down by party. Among Republicans, the average probability they assign to Trump winning is 76%, with more than one in five saying that Trump will win with 100% probability. Among Democrats, the average probability assigned to Biden winning is 74%, with almost 15% of them saying that Biden will win with 100% probability.

Figure 1 Distributions of perceived chances of Trump winning the 2020 presidential election

Notes: The figure plots the distribution of perceived chances of Trump winning the 2020 Presidential election, separately for each political leaning. All statistics are computed using sampling weights. “Other” includes respondents who when asked about their political affiliation chose Green party, Libertarian party, other party, “do not lean to any party”, or “prefer not to answer”.

These differences in probability distributions across party lines are not innocuous. Americans hold fundamentally different conditional expectations about the economy over the next year depending on the presidential winner, despite the fact that presidents seem to have little discernible effect on the economy, especially over short horizons (Blinder and Watson 2016). Republicans expect a fairly rosy economic scenario if Trump is elected but a very dire one if Biden wins, with unemployment expected to be 3% points higher under Biden after just one year. Democrats hold diametrically opposing views and expect calamity if Trump is re-elected but an economic boom if Biden wins.

Because both sets of voters are confident in their candidate winning, their unconditional forecasts about the economy are broadly similar. But this similarity masks fundamental disagreements about conditional expectations and the probability distributions associated with them. When the election is ultimately decided, one group of voters will become much more pessimistic than they have been so far. They may also be more likely to question the legitimacy of the election’s outcome if they did not foresee it as remotely possible. The winning group’s expectations, in contrast, will be largely unaffected since they already expected to win. As a result, the average macroeconomic outlook can deteriorate after the elections.

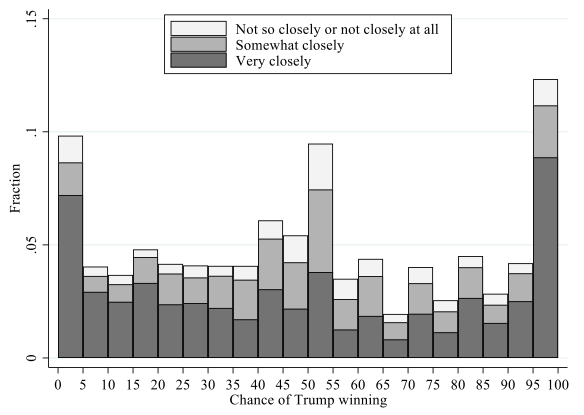

Why do individuals of different political persuasions hold such different views about the likely outcome of the election? We can rule out some potential explanations. For example, Republicans and Democrats are similar in the extent to which they get news from social media versus newspapers versus television. They are also similar in how much they claim to be paying attention to the election, with about 60% of each following the election very closely. But voters who pay close attention to the election are, if anything, less likely to agree about electoral outcomes than those who are paying less attention, as illustrated in Figure 2 below. It is precisely those voters paying close attention to the election who are likely to hold the most extreme views about whether Trump or Biden is likely to win. Those paying less attention to the economy are much more likely to think that the election is close to a toss-up.

Figure 2 Distributions of perceived chances of Trump winning the 2020 presidential election

Notes: The figure plots the distribution of perceived chances of Trump winning with a decomposition by how closely individuals follow the election. All statistics are computed using sampling weights.

This result suggests that it is the content of the news that attentive voters are receiving that are leading them to hold such disparate views. Indeed, there are sharp differences in voters’ preferred news sources. For example, with television, 40% of Democrats report that CNN is their favoured news channel (versus 23% of Republicans) while 50% of Republicans claim that Fox News is their favoured news channel (versus 17% of Democrats). Given the well-known differences in perspectives across news channels, this provides one possible rationale for the systematically different electoral outlook across the two parties (Della Vigna and Kaplan 2007, Gentzkow and Shapiro 2010).

One implication of having voters being so confident in the election outcome is that they should tend to be unmoved by new information that they receive since, with Bayesian learning, agents place little weight on new signals when their prior beliefs are tight. We test this prediction using a randomised control trial in which randomly selected participants are presented with recent (and very similar) polling data from different sources (Fox, ABC, and MSNBC). Consistent with Bayesian learning, we find that treated individuals tend to revise their beliefs toward the provided information relative to a control group, but quantitatively the revision is small on average. In fact, for Republicans and Democrats, the responses are effectively zero regardless of the news source (i.e. we find little evidence for an ‘echo chamber’). Instead, the views of many individuals of either party are so tightly held that they are unaffected by information that calls for a more nuanced view. Only for independents, or more generally for those who are less confident about the outcome of the election, do we find strong effects of new information on perceived electoral outcomes.

Interestingly, we find stronger effects of polling information if we include a description of the range of possible outcomes that is included within the margin of error. The baseline ABC poll, for example, points toward a 12-point lead for Biden but this could be as high as a 19-point lead or as low as 5-point lead. When presented this way to individuals, their perceived probability of either candidate winning shrinks more strongly toward 50-50 and away from extreme outcomes. One implication of this is that households likely do not understand, or are not sufficiently made aware of, the margins of error associated with polling data. Were news reports to emphasise the uncertainty around new polls rather than their point values, this would likely help the population avoid diverging toward such strong beliefs about which candidate is ‘certain’ to win.

The information treatments also allow us to assess whether changes in individuals’ perceptions of the likelihood of different electoral outcomes feed into their unconditional economic expectations. We can do so because we observe individual conditional expectations (i.e. what they expect for each of the two outcomes) as well as the change in the probability that they assign to each outcome. Combined with the prior (before the treatment) and posterior (after the treatment) unconditional forecasts of individuals, we can assess whether all of these beliefs are internally consistent. By and large, we find that as individuals change their probabilities over different outcomes, they revise their unconditional forecasts in a corresponding manner. This implies that when the election uncertainty is resolved and a winner is declared, the prior probabilities on the two possible outcomes will shift to the actual outcome and therefore individuals’ unconditional forecasts will adjust accordingly. Members of the losing party, given their pessimism about the economy under the other candidate, will therefore become significantly more pessimistic about the overall economic outlook. Members of the winning party will not become much more optimistic, since they already expected their candidate to win. Average optimism will therefore decline. A growing literature has found that changes in people’s expectations affect their decisions (e.g. Coibion et al. 2019b, D’Acunto et al. 2020). This suggests that election-driven changes in beliefs on the part of consumers will likely translate into their spending decisions as well and will put further downward pressure on an already struggling economy.

Conclusion

In a few days, many US citizens are going to wake up to an election outcome that they viewed as inconceivable. This will translate into widespread economic pessimism. To the extent that increasingly polarised voters perceived little chance of their candidate losing, the election outcome will undoubtedly be seen as illegitimate by a large share of the population. Ensuring that future voters can correctly distinguish between what they want to see happen and what is likely to happen will be fundamental to sustaining a functioning democracy.

References

Alesina, A, A Miano, and S Stantcheva (2020), “The Polarization of Reality,” American Economic Association Papers and Proceedings 110 324-328.

Blinder, A and M Watson (2016), “Presidents and the US Economy: An Econometric Investigation,” American Economic Review 106(4): 1015-1045.

Coibion, O, D Georgarakos, Y Gorodnichenko and M Van Rooij (2019b), “How Does Consumption Respond to News about Inflation? Field Evidence from a Randomized Control Trial,” NBER Working Paper w26106.

Coibion, O, Y Gorodnichenko and M Weber (2019), “Monetary Policy Communications and their Effects on Household Inflation Expectations,” NBER Working Paper w25482.

D’Acunto, F, D Hoang, and M Weber (2020), “Managing Households’ Expectations with Unconventional Policies”.

DellaVigna, S and E Kaplan (2007), “The Fox News Effect: Media Bias and Voting,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 122: 1187-1234.

Gentzkow, M and J M Shapiro (2010), “What Drives Media Slant? Evidence from U.S. Daily Newspapers,” Econometrica 78(1): 35-71.