In the aftermath of the Covid-19 pandemic, the US, like many other advanced economies, experienced inflation at levels not seen in 40 years. In this column, we address a key question raised by this development, namely, to what extent the recent spike in US inflation is driven by a change in its permanent component. This question is at the heart of the current economic debate, see for example, D’Acunto and Weber (2022) and Ha et al. (2021).

To identify the permanent component of inflation, in Schmitt-Grohé and Uribe (2022a) we use a semi-structural model of output, inflation, and the short-term interest rate. When the model is estimated on data covering the period 1900 to 2021, it predicts a modest increase in the permanent component of inflation. By contrast, when it is estimated using post-war data (1955 to 2021), the permanent component of inflation is predicted to have increased substantially.

One interpretation of this result is that the post-war data—dominated by the highly persistent inflation of the 1970s—leaves not much choice to the model but to interpret the 2021 inflation as also driven by low-frequency factors. By contrast, the pre-war era is rich in large and transitory inflationary spikes. Since a key characteristic of the 2021 increase in inflation was its speed and size, the model estimated on long data naturally associates it more with the pre-war inflation spikes than with the great inflation of the 1970s.

Empirical model

The empirical model is inspired by the dynamic stochastic general equilibrium (DSGE) literature but features fewer cross-equation restrictions. Its structure is described in Schmitt-Grohé and Uribe (2022b). Here we briefly outline its key components. Output per capita, the inflation rate (), and the short-term nominal interest rate are assumed to be nonstationary. Output is assumed to be cointegrated with a nonstationary productivity shock and with a nonstationary natural rate shock. Inflation is assumed to be cointegrated with a nonstationary trend inflation shock () and the nominal interest rate is assumed to be cointegrated with the nonstationary trend inflation shock and the natural rate shock. In addition to the three trend components just described, the model includes a stationary monetary shock and a stationary real shock. The model is estimated using annual US data on output, inflation, and the short-term nominal interest rate for the period 1900 to 2021. The data are taken from the Jordà-Schularick-Taylor Macrohistory Database (see Jordà et al. 2017) until 2017 and extended to 2021. The aim of the econometric analysis is to infer the path of the permanent component of inflation and to ascertain how closely it tracks actual inflation post Covid-19.

The permanent component of inflation

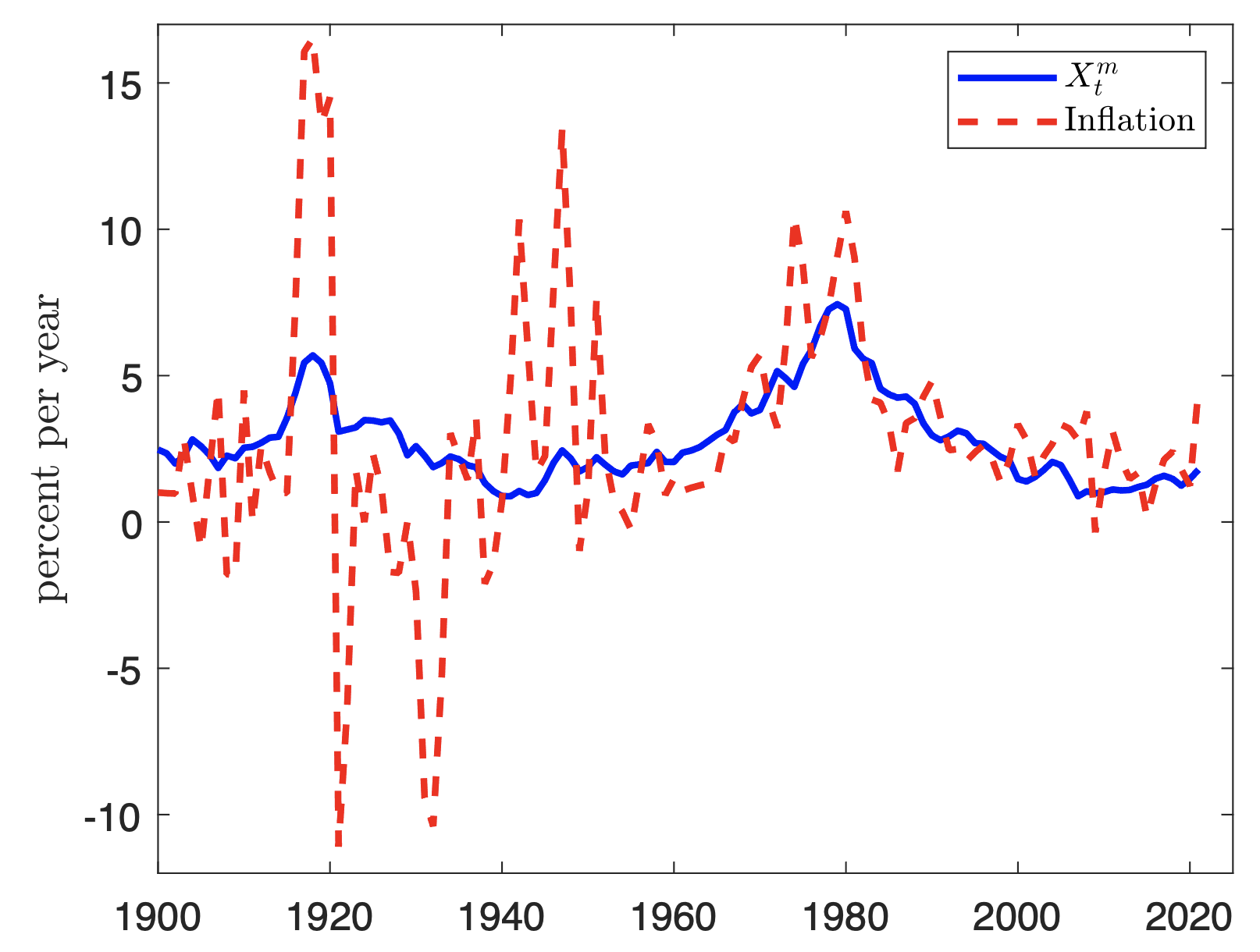

Figure 1 plots the estimated path of the permanent component of inflation over the period 1900 to 2021. For comparison, the figure also plots the actual inflation rate.

Observed inflation displays distinct characteristics in the pre- and post-war periods. In the pre-war period, inflation is highly volatile and spikes in inflation and deflation are typically short lived. As a result, the model interprets these episodes as mostly transitory, that is, not primarily driven by movements in the permanent component of inflation.

A case in point is the observed inflation spike around the 1918 influenza pandemic. Between 1915 and 1918 inflation increased from 1% to 17% and then fell quickly to -11% by 1921. At the same time, the permanent component of inflation was relatively little changed; it increased by two percentage points between 1915 and 1918 and then fell by two percentage points between 1918 and 1921. Figure 1 further shows that the dynamics of inflation and its trend component are quite different in the post-war to pre-Covid-19 era. This period is dominated by the great inflation of the 1970s. Contrary to what happened during the pre-war period, this inflation episode was slow in building up. Inflation began to increase from a level of 2% in the mid-1960s to a peak of 10% in 1980. The figure shows that inflation accelerated for about 15 years. The return of inflation to levels observed in the mid-1960s took another six years. To a large extent, the model accounts for the great inflation of the 1970s with a significant movement in the permanent component of inflation. Between 1960 and 1980 the model estimates that the permanent component of inflation rose five percentage points. In fact, its largest increase over the entire 1900 to 2021 sample takes place during this episode.

Figure 1 Inflation and its permanent component: Sample 1900 to 2021

Notes: The permanent component of inflation is computed by two-sided smoothing using the Kalman filter. It is normalised by adding a constant to match the sample mean of inflation.

A key characteristic of the post-Covid-19 inflation hike is its speed. From 2019, the year before the onset of the pandemic, to 2021, the annual rate of inflation rose by 277 basis points. The model interprets this sudden spike in inflation as being more akin to those observed in the pre-war period than to the great inflation of the 1970s. Specifically, of the 277 basis point increase in inflation observed between 2019 and 2021, the permanent component of inflation accounts for only 55 basis points. Thus, according to the model the 2021 inflation burst was not predominantly driven by an increase in the permanent component of inflation.

How important is the inclusion of pre-war data in arriving at this conclusion? This question is relevant because most of the existing literature on the joint behaviour of inflation, output, and the nominal interest uses data that starts only after WWII. We therefore next examine the predictions of the model when estimated on post-war data. Specifically, we re-estimate the model on a sample starting in 1955.

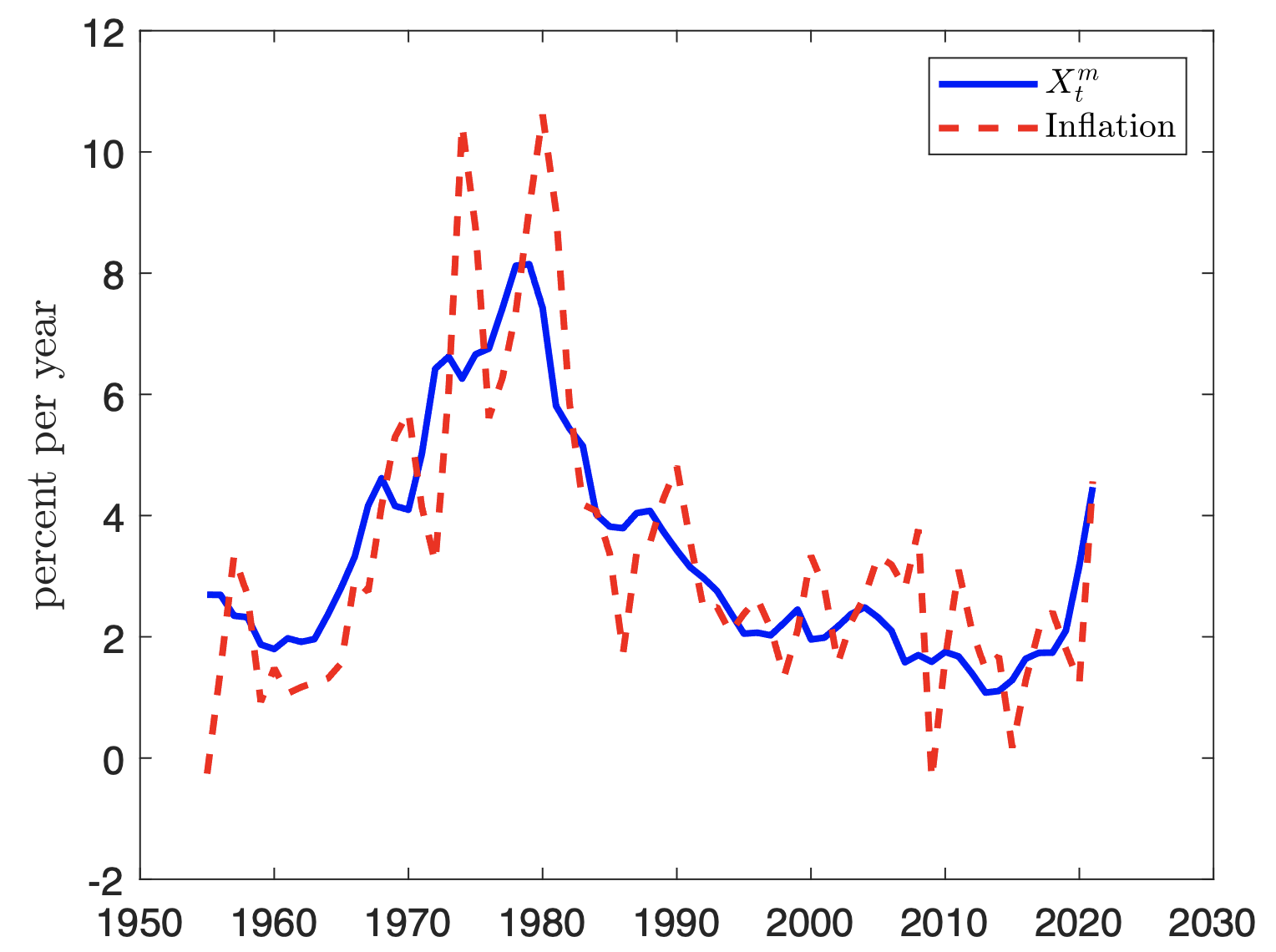

Figure 2 Inflation and its permanent component: Sample 1955 to 2021

Notes: The permanent component of inflation is computed by two-sided smoothing using the Kalman filter. It is normalised by adding a constant to match the sample mean of inflation.

Figure 2 displays the inferred path of the permanent component of inflation and actual inflation. As in the estimate using data since 1900, the inflation of the 1970s is interpreted by the model as having a large permanent component. The key difference of this estimate relative to the one obtained when the model is estimated over the sample beginning in 1900 is that now almost all of the Covid-19 inflation spike is attributed to the permanent component of inflation . Specifically, between 2019 to 2021 the permanent component of inflation increases by 237 basis points, which is more than 80% of the total observed inflation increase of 277 basis points. So according to the model estimated on post-war data, the inflation burst associated with Covid-19 was to a large extend driven by the permanent component of inflation.

Conclusion

Modern business cycle analysis is a story told with post-war data. Before the Covid-19 pandemic this approach made sense. The volatile pre-war data seemed out of touch with the unprecedented stability witnessed in the post-war period and in particular since the Great Moderation. The Covid-19 pandemic has called this approach into question and has given renewed value to the information contained in pre-war macroeconomic indicators. It is now the post-war data that seem out of touch with current developments.

The analysis presented here serves as a proof of concept. Seen from the perspective of a model estimated on post-war data, the 2021 inflation spur is interpreted to be caused by a large increase in the permanent component of inflation. The reason is that the model was given little chance to conclude otherwise; the only other major prior inflation increase during this sample period turned out to be a protracted one, which naturally is ascribed to the permanent component—not just by the present model but also by the majority of existing models of US inflation. As a result, trend inflation follows closely actual inflation. However, once the sample is expanded to include the sudden, large, and short-lived swings in inflation observed in the first half of the 20th century, the same model attributes a major fraction of the post Covid-19 inflation to its transitory component.

Looking ahead, recent studies point in the direction that climate change will raise economic volatility around the globe. Thus, until sufficient data accumulates under this seemingly emerging new regime, long historical time series data could be a valuable input to business cycle analysis.

References

D’Acunto, F and M Weber (2022), “Rising inflation is worrisome. But not for the reasons you think”, VoxEU.org, 4 January.

Ha, J, A Kose and F Ohnsorge (2021), “Inflationary pressures: Likely temporary but challenging for policy design”, VoxEU.org, 14 July.

Jordà, O, M Schularick and A M Taylor (2017), “Macrofinancial History and the New Business Cycle Facts”, in M Eichenbaum and J A Parker (eds.), NBER Macroeconomics Annual 2016, Volume 31, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 213-263.

Schmitt-Grohé, S and M Uribe (2022a), “What Do Long Data Tell Us About the Inflation Hike Post COVID-19 Pandemic?”, NBER Working Paper No. 30357.

Schmitt-Grohé, S and M Uribe (2022b), “The Macroeconomic Consequences of Natural Rate Shocks: An Empirical Investigation”, NBER Working Paper No. 30337.