Economists who work on health insurance worry a lot about ‘adverse selection’. But adverse selection is not the only source of information asymmetry in healthcare. Usually, patients are the ones who do not know what they are suffering from, and doctors are the ones who have the ability to find out. Unfortunately, doctors who do not have their patients’ best interests at heart may use that resulting asymmetry of information to their own benefit; patients can never be sure that they really needed what they got or got what they needed. This problem of ‘credence’ arises in virtually every interaction with the healthcare system and arguably defines critical aspects of how health systems are designed. For instance, in the US, Arrow (1963) notes that the need to build trust between doctors and patients was probably the reason why the healthcare industry was dominated (at that time!) by non-profits.

Responding to the same sentiment, that profits and healthcare do not mix, healthcare systems in low- and middle-income countries were styled on the UK’s NHS, with doctors paid on salary and funded through general taxation. Yet, by the year 2000 it was evident that something had gone badly wrong. Despite the availability of highly subsidised care through the public sector, many patients opted-out of the public system entirely and financed their care in the private sector through out-of-pocket expenditures (World Health Organization 2020b, Grépin 2016, Gertler and Gruber 2002). Summarising the situation at the turn of the 21st century, Pauly et al. (2006) observed that:

“Virtually every developing country with a functioning government uses publicly funded and managed systems for third-party payment for medical care. …(but) in many developing countries, this system has failed to provide adequate financial protection for its citizens and adequate access to care. The gap shows up in the form of private out-of-pocket spending for services that “universal insurance” cannot or does not supply.”

As we argue in our new paper (Das and Do 2023), health insurance emerged as a magic bullet that could solve the multiple problems that low- and middle-income countries were facing when it came to health financing and delivery. It could: (a) provide a dedicated source of funds to health ministries, (b) expand subsidies for care to the private sector, where quality was thought to be higher (or, in Latin America, decrease the discrepancy in care between facilities that catered to formally employed individuals and others), (c) provide incentives to public sector clinics through redesigned reimbursements or ‘strategic purchasing’ (World Health Organization 2000a, Hanson et al. 2019, and Londoño and Frenk 1997), and (d) improve patient welfare by replacing ex-post out-of-pocket expenditures with ex-ante health insurance premiums, thus offering much-needed financial protection for citizens.

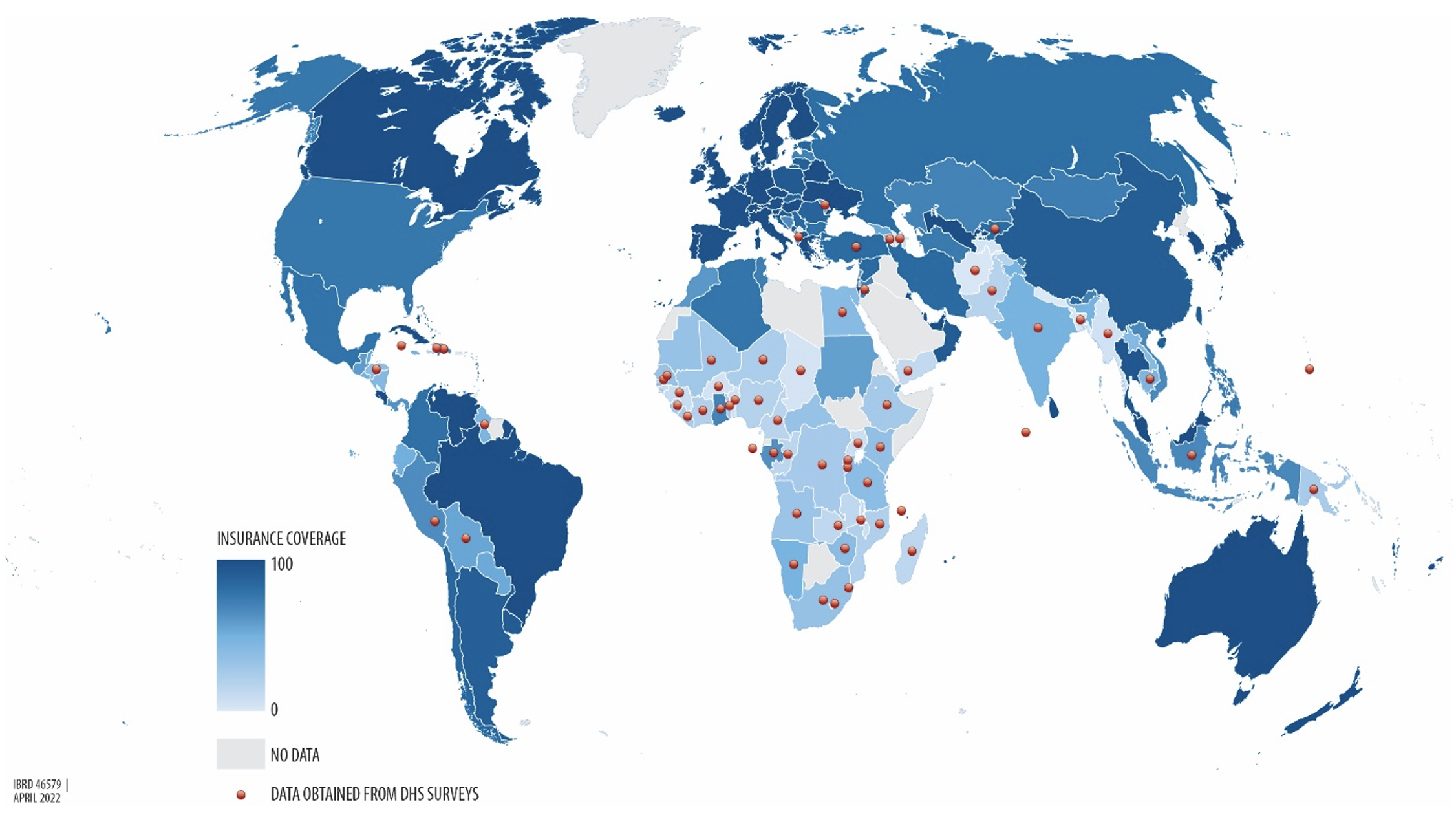

Twenty years later, clear progress has been made, with some countries expanding coverage of health insurance at an extraordinary speed. Coverage is now near universal for several countries in East and Central Asia and Latin America and middling in India and some sub-Saharan countries (Namibia, Sudan, Rwanda, Ghana). Most of this growth in coverage is very recent. For instance, health insurance coverage in Rwanda increased from 20% in 2005 to 83% by 2019, from 28% in 1998 to 88% in 2013 in Turkey, and from 40% in 2012 to 61% in 2017 in Indonesia.

Figure 1 Health insurance coverage across the world

Notes: The data in this map show the percentage of health insurance coverage for the latest year for which data or estimates are available. For countries with a red dot, health insurance coverage data are obtained from the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS). For the other countries, the data come from OECD health data (Scheil-Adlung 2014). The grey zones represent locations where data were not available. See Appendix A of Das and Do (2023) for documentation of the DHS data used for this analysis.

But have health insurance schemes met their multiple objectives? Our paper investigates this question in three sections related to the structure of health insurance schemes, their outcomes, and the mechanisms that translate structure to outcomes.

The structure of health insurance schemes

In terms of the structure of health insurance schemes, it seems that countries have coalesced on how to finance health insurance schemes but not on how to reimburse healthcare providers for their services.

As to the first, countries have all but given up on the idea that citizens will pay the premiums necessary to support the scheme. Instead, health insurance everywhere is now heavily subsidised or provided for free to households and funded through either mandatory participation or general taxation. From the consumer’s side, such schemes are then best understood as an expansion of the network of free and subsidised care that the public sector continues to provide, rather than insurance per se. On the provider side, health insurance brings about new contracting mechanisms that modify reimbursements, both for public and private providers.

When it comes to the precise form of reimbursements, however, we find a bewildering array of arrangements across countries. For instance, the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine’s RESYST study documents 19 different purchasing mechanisms in ten low- and middle-income countries (Hanson et al. 2019) that range from fee-for-service to capitation (physicians agree to a fixed amount per patient under their care for a given duration) to more complicated reimbursements that involve different levels of aggregation across diseases and populations. Further, prices are set through individual or group negotiations or through administrative pricing—the latter vary in their degree of sophistication, ranging from average accounting costs of procedures to more sophisticated, risk-adjusted marginal cost pricing.

The point here is not that reimbursement models are ‘context-specific’, but that it is really hard to get the ‘right’ reimbursement rates, and this difficulty has led to the proliferation of multiple models with constant changes as countries discard one model in favour of another.

Outcomes

Turning to outcomes, there is remarkable consistency in what we found in our review, drawing from an extensive literature that for the most part relies on experimental or quasi-experimental evidence. We report three broad findings:

- Financial protection and health care utilisation improve. The good news is that, as expected, insured households experience a decline in out-of-pocket and catastrophic expenditures: health insurance reduces financial risk. Healthcare service utilisation also increases for all kinds of services ranging from preventive to outpatient and inpatient care.

- Health outcomes do not seem to have changed much. The bad news is that there is little evidence that increased utilisation has led to better health outcomes. Although this finding is remarkably consistent across multiple settings and programmes, we do caution that health outcomes are hard to detect in the smaller sample sizes typical of these studies.

- Take-up is low. We also find that, without substantial financial subsidies, take-up is almost zero. There is little consensus on why this is so; studies have suggested that non-price costs, such as administrative red tape, may play a role, but equally, the anticipation of little health improvement might be a factor.

Mechanisms: Supply constraints are not the problem

One reason why health insurance has increased utilisation but not health outcomes could be supply constraints: if the health sector in low- and middle-income countries was already operating at full capacity (both in terms of physical capacity and knowledge), changing reimbursements and expanding choice will make little difference. We argue that this argument is incorrect, looking at three different widely believed sources of supply constraints.

Overcrowded facilities? First, workforce utilisation does not indicate significant overcrowding. In several low- and middle-income countries, a large portion of healthcare providers sees a low number of patients per day, with some seeing fewer than five patients. Even the busiest doctors spend less than half a day, and studies examining the link between patient load and quality of care find no impact.

Insufficient infrastructure? Second, although insufficient infrastructure could provide an alternate source of constraints, multiple studies find that infrastructure and equipment are, at best, weakly associated with better quality care (Leslie et al. 2017, Bedoya et al. 2017, Das et al. 2012). Structural improvements may be necessary, but are far from sufficient to guarantee better quality care.

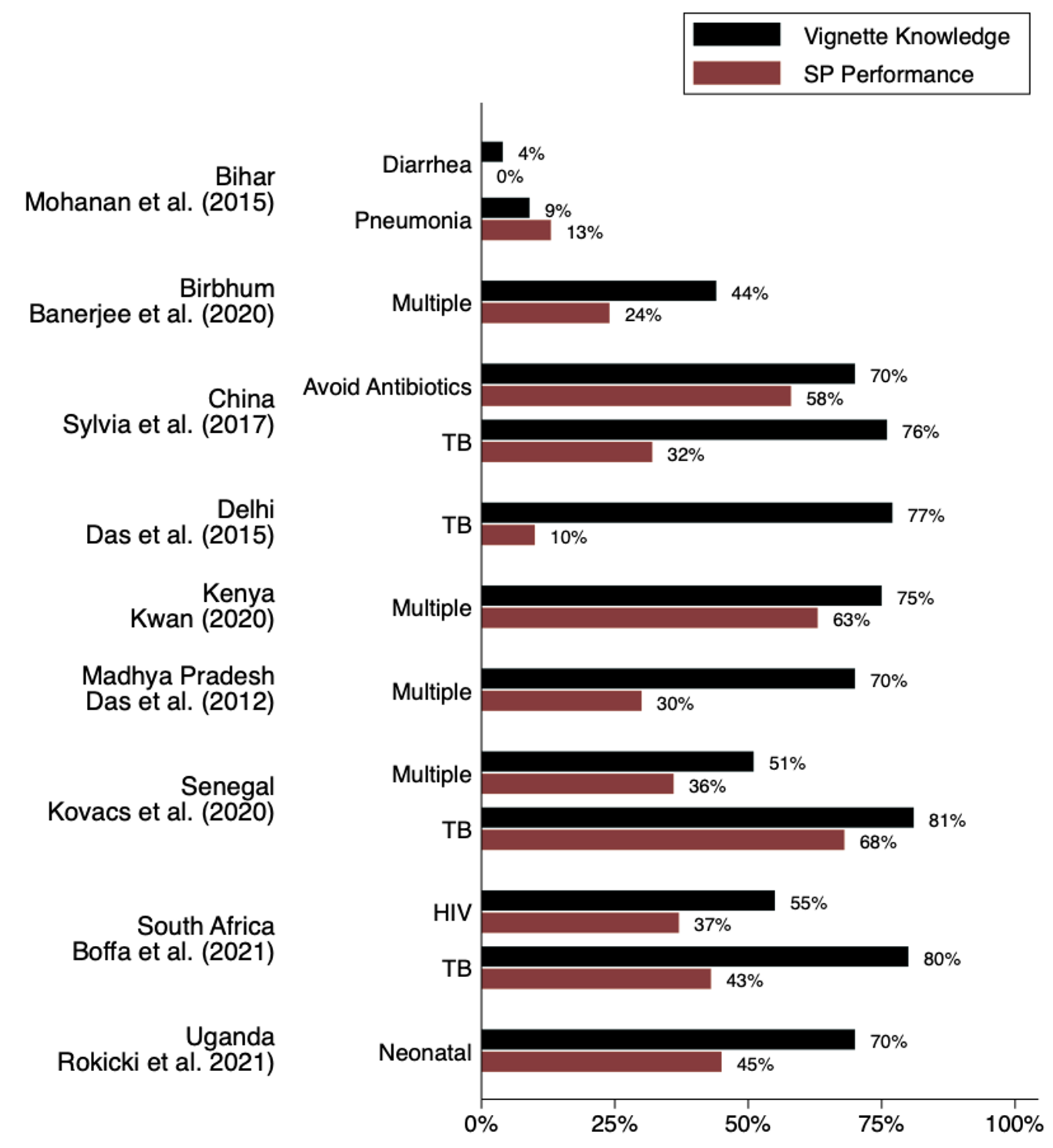

Poor medical training? Finally, healthcare providers may already be operating at their knowledge frontier. However, all the evidence suggests that there is a big gap between what providers know to do and what they actually do in their clinical practice. Das et al. (2008) first documented this phenomenon and labelled it the ‘know-do gap’. Since then, multiple studies have compared performance on medical tests with clinical performance for the same patient (using methods akin to audit studies in economics) and every study finds significant gaps between what doctors say they will do and what they actually do when faced with the same patient (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Know-do gaps between medical vignettes and standardised patients

Notes: This figure illustrates ‘know-do gaps’ estimated from several studies which used both medical vignettes and standardised patients with similar (or the same) samples of providers and conditions. ‘Vignette knowledge’ is defined as the share of providers who said they would offer the patient in the indicated case scenario at least minimal correct treatment according to study definitions, regardless of what else they did. (In the ‘Avoid Antibiotics’ case it is the percentage of providers who said they would not give antibiotics). ‘SP performance’ is the proportion of providers who did the same when presented with an actual standardised patient with the same case scenario.

Source: Das and Do (2023). For the original studies, we list an abbreviated reference; a full list of references is included in Das and Do (2023).

Mechanisms: Provider moral hazard probably is the problem

Instead of supply constraints, an alternate hypothesis more consistent with the evidence is that behavioural responses among providers to poorly designed reimbursement schedules have significantly undermined the objectives of health insurance. These responses range from outright denial of care to lack of adherence to the legislated prices to the manipulation of what patients receive.

The relatively sparse literature on this topic falls into three groups. One group of case studies points to dramatic – and implausibly large — increases in certain types of procedures (such as hysterectomies or cataract surgeries), arguably driven by reimbursements that exceed costs (Averill and Dransfield 2013, Rana 2017). A second group of studies varies the insurance status among standardised (mystery) patients; these studies find that unnecessary care increases for patients with insurance, without any improvements in other aspects of the clinical interaction (Sripathy 2020, Lu 2014). Finally, a third study combines administrative claims data with household surveys to show (a) that patients pay far more for the treatment compared to the legislated prices and (b) that hospitals react rapidly to changes in reimbursed rates. For instance, the rates of deliveries with and without an episiotomy react rapidly to changes in the relative prices of different procedures (Jain 2021).

This is by no means the comprehensive evidence that we need to causally link behavioural responses among providers to the arrival of health insurance—that evidence does not (yet) exist. But wherever researchers have looked at how health insurance effects provider behaviour, they typically find that quality of care becomes worse as providers respond to the incentives inherent in reimbursement packages.

Conclusion

Increasing health insurance coverage has provided greater financial protection to households but has not improved health outcomes systematically or provided a dedicated source of health financing. These failures do not reflect fundamental constraints in the system, but rather poorly designed reimbursement schemes that triggered behavioural responses among healthcare providers, ultimately undermining the objectives of these schemes. The challenge for the design of health insurance schemes going forward is to recognise the inseparability between the financial protection and facilitated access that such schemes offer patients and the incentive effects of reimbursement packages for provider behaviour. Ultimately, it is the prices in the crises that truly matter.

References

Arrow, K J (1963), “Uncertainty and the Welfare Economics of Medical Care”, American Economic Review 53(5): 941–73.

Averill, C and S Dransfield (2013), Unregulated and Unaccountable: How the Private Health Care Sector in India Is Putting Women’s Lives at Risk, Oxfam International.

Bedoya, G, A Dolinger, K Rogo, N Mwaura, F Wafula, J Coarasa, A Goicoechea and J Das (2017), “Observations of infection prevention and control practices in primary health care, Kenya”, Bulletin of the World health Organization 95(7): 503-516.

Das, J and Q-T Do (2023), "The Prices in the Crises: What We Are Learning from 20 Years of Health Insurance in Low-and Middle-Income Countries", Journal of Economic Perspectives 37(2): 123-152.

Das, J, J Hammer and K Leonard (2008), “The Quality of Medical Advice in Low-Income Countries”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 22(2): 93–114.

Das, J, A Holla, V Das, M Mohanan, D Tabak and B Chan (2012), “In Urban and Rural India, a Standardized Patient Study Showed Low Levels of Provider Training and Huge Quality Gaps”, Health Affairs 31(12): 2774–84.

Gertler, P and J Gruber (2002), “Insuring Consumption Against Illness”, American Economic Review 92(1): 51–70.

Grépin, K A (2016), “Private Sector An Important But Not Dominant Provider Of Key Health Services In Low- And Middle-Income Countries”, Health Affairs 35(7): 1214–21.

Hanson, K, E Barasa, A Honda, W Panichkriangkrai and W Patcharanarumol (2019), “Strategic Purchasing: The Neglected Health Financing Function for Pursuing Universal Health Coverage in Low- and Middle-Income Countries”, International Journal of Health Policy and Management 8(8): 501–4.

Jain, R (2021), “Private Hospital Behavior Under Government Health Insurance: Evidence from India”, in 2021 World Congress on Health Economics, iHEA.

Leslie, H H, Z Sun and M E Kruk (2017), "Association between infrastructure and observed quality of care in 4 healthcare services: A cross-sectional study of 4,300 facilities in 8 countries", PLoS medicine 14(12): e1002464.

Londoño, J-L and J Frenk (1997), “Structured Pluralism: Towards an Innovative Model for Health System Reform in Latin America”, Health Policy 41(1): 1–36.

Lu, F (2014), “Insurance Coverage and Agency Problems in Doctor Prescriptions: Evidence from a Field Experiment in China”, Journal of Development Economics 106: 156–67, January.

Pauly, M V, P Zweifel, R M Scheffler, A S Preker and M Bassett (2006), “Private Health Insurance In Developing Countries”, Health Affairs 25(2): 369–79.

Rana, K (2017), “Health Insurance for the Poor, or Privatization by Stealth? A Study on the Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana (RSBY) in India”, PhD Dissertation, Harvard University.

Scheil-Adlung, X (2014), Universal Health Protection: Progress to Date and the Way Forward, International Labour Organization, OECD.Stat.

Sripathy, A (2020), “Rationalising Health Care Provision under Market Incentives: Experimental Evidence from South Africa”, PhD Dissertation, The London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE).

World Health Organization (2000a), The World Health Report 2000: Health Systems - Improving Performance, World Health Organization.

World Health Organization (2020b), Private Sector Landscape in Mixed Health Systems, World Health Organization.