In 1945, Jackson Pollock conceded that “the important painting of the last hundred years was done in France. American painters have generally missed the point of modern painting from beginning to end.” Nonetheless, he had no desire to study in Europe – “I don't see why the problem of modern painting can't be solved as well here as elsewhere.”

Pollock and a small group of his peers created a revolution that decisively shifted the centre of the advanced art world from Paris to New York. In 1946, the critic Clement Greenberg observed that “the School of Paris remains still the creative fountainhead of modern art,” but just two years later he declared that with the recent achievements of American artists, “the conclusion forces itself, much to our own surprise, that the main premises of Western art have at last migrated to the United States.”

Pollock was a leader of abstract expressionism, and he maintained that its revolution was not merely geographic, as he asserted in 1956 that “we’ve changed the nature of painting.” He and his colleagues believed that the hegemony of abstraction would be durable – Adolph Gottlieb predicted that “We're going to have perhaps a thousand years of non-representational painting.”

The abstract expressionists were greater painters than prophets. The supremacy of abstraction lasted not a millennium, but barely a decade before it was overthrown by yet another revolution. The contrasting attitudes and practices of those who made these two revolutions produced distinctive patterns in their careers. Quantitative analysis can now yield deeper insight into the basic changes in the nature of painting that occurred in New York in the decades after WWII.

Experimental and conceptual revolutions

The abstract expressionists were experimental innovators who worked by trial and error. A shared basic tenet was the rejection of planning – a painting should not be the transcription of a previously formulated idea; the abstract expressionists favoured vision over ideas, and spontaneity over preconception. The critic Harold Rosenberg suggested that they should properly be called action painters, on the grounds that their paintings were records of their own making – “What was to go on the canvas was not a picture but an event.”

The leaders of the next generation shared a set of conceptual attitudes and practices. Roy Lichtenstein's pop images of comic strips appeared to have little in common with Frank Stella’s parallel black stripes, but Lichtenstein explained that they had a shared basis, “that before you start painting the painting, you know exactly what it's going to look like.” In deliberate contrast to the personal gestures of the abstract expressionists, a common feature of the new art was impersonality –some of these artists used mechanical production, and others simulated it.

Pricing creativity

Art history is the history of innovations – the most important artists are those who change their discipline, and their most important works are those that announce their innovations. The auction market values vast numbers of paintings. The prices it generates can be used to measure an artist’s creative life cycle – hedonic regression analysis can trace out an age-price profile for an artist, the peak of which identifies the artist’s most innovative period.

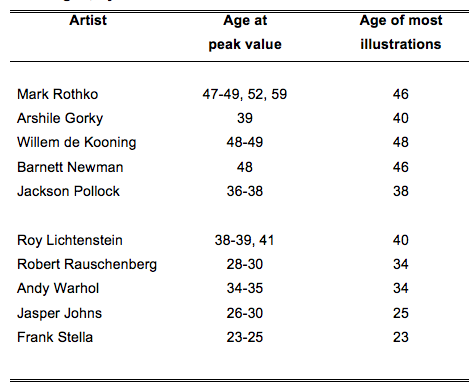

Table 1 presents estimates drawn from non-parametric regressions for the five leading artists of each cohort, as identified by art scholars. Using auction sales from 1980-2016, the natural log of a painting’s price was specified as a function of the artist’s age when he executed the painting, measured as a series of binary variables, with controls for the size of the work, its support, and its date of sale. Table 1 summarises the ages at peak value implied by the regressions. To compare these estimates to the opinions of art scholars, the table also includes the age from which each artist's work was most frequently reproduced in 50 textbooks of art history published since 2000.

Table 1 Peak ages, by artist

The two sources yield similar results, as the difference in estimated peak ages is within two years for 9 of the 10 artists. This supports the conclusion of earlier studies that there is close agreement between the auction market and scholarly judgments as to when important painters have produced their best work.

Table 1 also points to a pronounced difference in the creative life cycles of the two cohorts. For example, the peak prices for three of the five abstract expressionists were for work done from ages 47-59, whereas those for three of the five of the second group occurred at ages 23-30. The median peak age of 46 for the abstract expressionists from textbook illustrations was fully 12 years above the median of 34 for the second cohort. Both sources thus indicate that experience increased the creativity of the experimental abstract expressionists, but decreased that of their conceptual successors.

From old masters to young geniuses

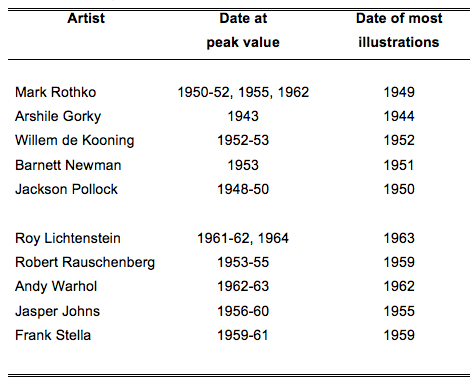

Table 2 shows the dates that correspond to the peak ages of Table 1. These neatly identify the high points of the two revolutions.

Table 2 Peak dates, by artist

The heyday of abstract expressionism – the creative peaks of its greatest members – began with Pollock's masterpieces of the late 1940s, and continued with the full development of de Kooning and Rothko in the early 1950s. But the next generation’s attack on abstract expressionism began almost immediately, with Rauschenberg’s invention of combines in the mid-1950s and Johns’ paintings of flags and targets in the late 1950s. The conceptual revolution reached its peak with the startling innovation of pop art by Lichtenstein and Warhol in the early 1960s.

Quantifying revolution

Shortly after the end of WWII, a small group of American painters made a revolution by creating bold new forms of abstract art, and in the process succeeded in making New York the centre of Western art. Their innovations were the result of extended experimentation, as they searched for personal techniques and images to satisfy their aesthetic goals, and they made their greatest contributions late in their lives – Pollock began to make his greatest works at 36, and the other leaders of the group entered their most creative periods from 39 through 48.

Almost as soon as the revolution had been achieved, the abstract expressionists were challenged by a group of younger artists, who rejected their visual artistic criteria in favour of new forms of art based on ideas, often expressed with mechanical production, use of manufactured products, and images derived from photography. Their radical new ideas arrived early in their lives – among the leaders, only Lichtenstein made his greatest works past the age of 35, and three entered their most creative periods in their 20s. The abstract expressionists were outraged at being displaced by artists decades younger than themselves who had not had to toil in obscurity to earn their success, and whose art appeared to mock the art and values of their elders. But this second revolution swept through the advanced art world, and began an era of conceptual art that continues today.

The sharp contrast between the highly personal art of the abstract expressionists and the impersonality and objectivity of their successors is well-known to art scholars, who have considered these revolutions to be beyond the reach of useful quantitative analysis. Now, however, quantitative evidence has provided a systematic basis for dating these revolutions, and creating a precise picture of the contrasting life cycles of creativity of the experimental old masters of Abstract Expressionism and the conceptual young geniuses of Pop Art.

References

Galenson, D (2006), Old Masters and Young Geniuses, Princeton University Press.

Galenson, D (2009), Conceptual Revolutions in Twentieth-Century Art, Cambridge University Press.

Galenson, D (2017), “Pricing revolution: from Abstract Expressionism to Pop Art”, Becker Friedman Institute, Working paper 2017-14.

Greenberg, C (1986), The Collected Essays and Criticism, Vol. 2, University of Chicago Press.

Karmel, P (1999), Jackson Pollock, Museum of Modern Art.

Rosenberg, H (1994), The Tradition of the New, Da Capo Press.

Sylvester, D (2001), Interviews with American Artists, Yale University Press.